Sentence diagramming

« previous post | next post »

This is a guest post by Dick Hudson, who has promised a later submission about his experience helping to organize the re-introduction of grammatical analysis in the British school curriculum. This post gives some of his reflections on the pre-history of the grammarless state that he played a role in changing.

What tools does a grammarian need? A brain helps, and so does a computer, but surely one of our most essential tools is some kind of diagramming system. How can you think about a sentence's structure without displaying it visually? Geographers have maps; mathematicians have equations; musicians have musical notation; economists have graphs; and grammarians have trees.

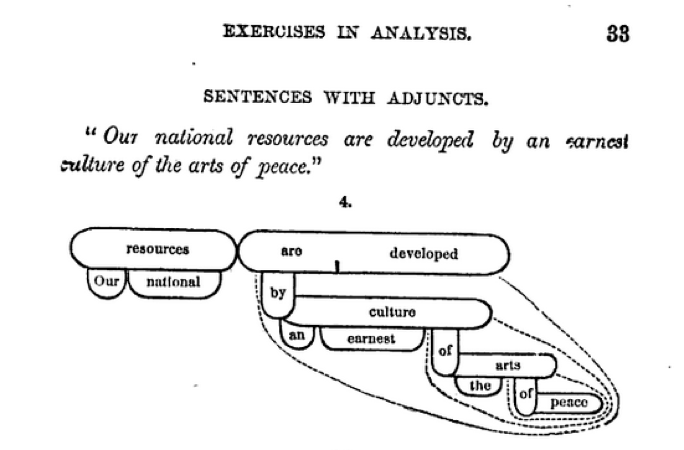

It wasn't always so. Grammarians spent several thousand years trying to think about syntax without diagrams, but it was hard, and they didn't get very far into structural details. For thousands of years they didn't even have word-spaces or punctuation. It was only in the early nineteenth century that an American, Stephen Watkins Clark, achieved the breakthrough for which he has received virtually no credit since – how many of us even know his name? In 1847 he published the idea of drawing a kind of map to show a sentence's physiology. Admittedly, his implementation of the idea wasn't great, because it involved rather clumsy bubbles. Here's an example (applied to a typically worthy sentence; the diagram comes courtesy of Google Books):

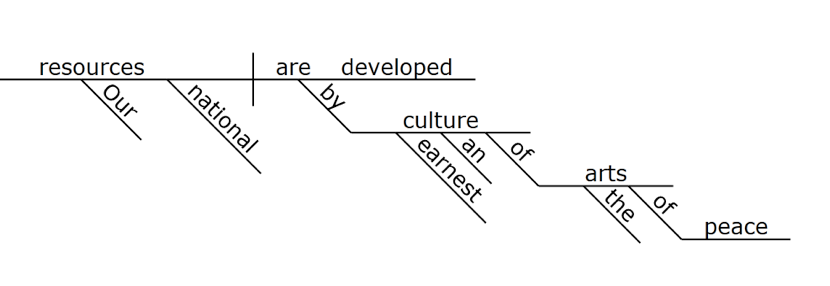

Just thirty years later, two other Americans, Alonzo Reed and Brainerd Kellogg, showed typical American marketing skills with a better implementation using lines instead of bubbles, like this:

A number of things are remarkable about this diagram. First, it's a product not of the nineteenth century, but of our twenty-first century, being generated by an online parser. The Reed and Kellogg system is still going strong, nearly 150 years later. For a long time 'sentence diagramming' flourished throughout the American school system, and although it was strongly condemned as a useless waste of time in the 1970s, it still persists in many schools. Not only that, but it spread well beyond the USA, so a very similar system is still taught in many European countries (though not, alas, in the UK); for example, schools in the Czech Republic teach sentence diagramming so successfully that researchers are investigating the possibility of including school children's analyses in a working tree-bank of analysed sentences. You yourself may remember sentence diagramming from your own school days; indeed, it may be because of this that you're reading this blog, because a lot of people loved it.

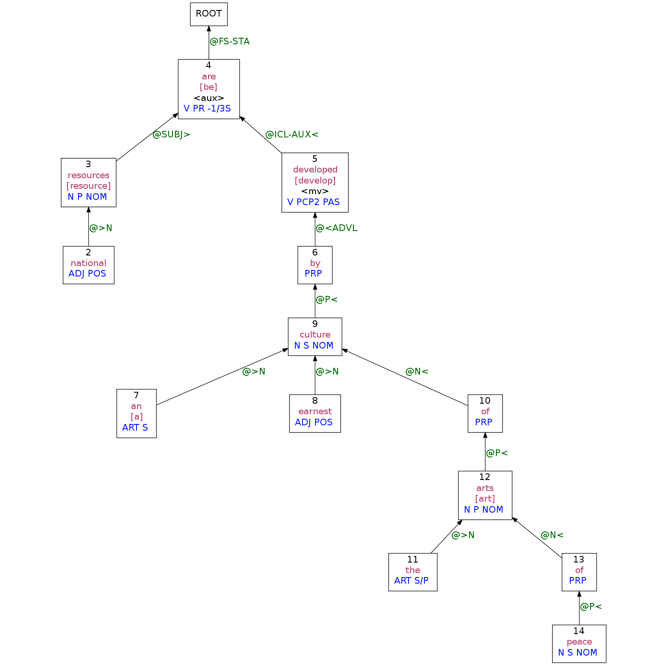

The second remarkable thing about Reed and Kellogg diagrams is that they are not in fact part of the tool-kit of any academic linguists. They belong to the world of school-teaching. Syntacticians everywhere have been deeply influenced by the idea of representing a sentence's structure with a diagram, but we have all moved on. In Europe, some linguists saw an opportunity to improve school teaching by making the diagrams even better. The classic example is the French linguist Lucien Tesnière who applied ideas that were already circulating in the Linguistic Circle of Prague (remember the earlier mention of the Czech Republic?) to school grammars. His innovation was the 'stemma' (and, incidentally, dependency grammar), which looked rather like Reed and Kellogg diagrams but culminated in a single top node for the root verb. Here's another diagram for the same sentence.

This diagram is also interesting in its own right, because, like the previous one, it was generated by an online parser (which, like most parsers, makes mistakes – what's happened to the first word, "our"?) This time, the parser is part of a Danish website for applying current linguistic theory to the teaching of grammar in schools – surely just the kind of development that academic linguists should celebrate.

But what about the United States, where it all started? As mentioned earlier, sentence diagramming seems to have flourished everywhere till the 1970s, so most of the American structuralists, including Bloomfield himself, must have done it at school. At the very least it must have shown them that a sentence has a structure that can be displayed visually. And yet (so far as I know) they never mentioned it even when they used trees to show constituent structure. Less still did they see themselves as improving it to make it work better in schools (as they could so easily have done, e.g. by making it sensitive to word order).

And in the UK (where I live)? We had a home-grown alternative to Reed and Kellogg (invented by Nesfield in the late nineteenth century, and still in use in my school during the 1950s), but it used columns rather than diagrams. I have no idea why we didn't buy Reed and Kellogg, but we didn't; and worse than that, we started the big international campaign against all grammar teaching (with or without diagrams) at school. This time the Americans followed, and the disease spread throughout the English-speaking world and beyond. As we struggle to cope with the effects of that disaster, it's worth pondering the history of it all.

Three cheers for Stephen Watkins Clark and his bubbles! Nearly two centuries later, where would modern linguistics have been without him? And even more importantly, where would those countless generations of bright school-kids (and teachers) have found their fun?

The above is a guest post by Dick Hudson. Some earlier LL posts on related topics:

"Personal and intellectual history of sentence diagrams", 10/14/2004

"Nominee for the Trent Reznor Prize", 4/14/2012

"Diagramming Sentences", 4/14/2013

"Putting grammar back in grammar schools: A modest proposal", 12/25/2013

"School grammar, Round two", 12/30/2012

I should also add that dependency diagrams and constituent-structure diagrams are more or less notational variants, and that these days, people often translate treebanks back and forth between dependency and CS versions.

quixote said,

January 1, 2014 @ 1:23 pm

I remember sentence diagramming in sixth or seventh grade. I was a rather precocious kid, but it was the first time it occurred to me that "parts of speech" actually meant something, and that those parts fitted together in specific ways, and that it was possible to think about it visually. As a near-100% visual learner, it was a wonderful aha! moment for me.

Sad that so many generations of students have been deprived of it, but good to hear it may be coming back.

Victor Mair said,

January 1, 2014 @ 2:09 pm

I loved sentence diagramming when I was in junior high school and high school. It made the acquisition of linguistic analytical skills positively fun. I too feel sorry that students nowadays apparently do not have the opportunity to do it.

Rod Johnson said,

January 1, 2014 @ 2:53 pm

Just a historical tangent: you can trace Tesniere's dependency ideas back through the Prague Circle to the Third Historical Investigation of Edmund Husserl, "On the Theory of Parts and Wholes," (1900) where he moves from a part-whole based ontology (i.e., constituency) to a "foundation" based one (i.e., dependency). It's fascinating to see the two approaches in embryo, as it were. Husserl addressed the Prague Circle on a few occasions. Tesniere visited the Circle at least a couple times (as, I believe, did Louis Hjelmslev, who covered some similar territory, and Anton Reichling, whose Het Woord (1935) was another, more explicitly phenomenological work). I'm pretty sure Jakobson's treatment of distinctive features was influenced by Husserl's "moments" (parts that can't exist independently) as well. I think Husserl was a important and largely unrecognized influence on early structuralism in Europe. I hope some historian of linguistics takes a look at this some day.

Alan Gunn said,

January 1, 2014 @ 3:47 pm

Is it really true that diagramming sentences flourished in the US until the 1970s? In the 1940s and '50s, I attended three grade schools, two junior high schools and one high school (we moved a lot). In none of these schools (mostly in upstate NY, but one miserable year in Louisiana) did we ever diagram a sentence. English classes consisted mostly of reading lots of things, many of them worth reading, and writing short papers, usually about patriotic stuff. Instruction in "grammar" was conspicuously absent. Maybe my experience was unusual, but the rest of my schooling seems to have been pretty much what everybody else got.

Tom Pollard said,

January 1, 2014 @ 6:06 pm

I was taught sentence diagramming in the sixth grade in 1973, in the Fairfax County Public Schools (Washington D.C. suburbs). I don't recall running into it again in the rest of my schooling, though, and suspect I might just have been lucky to get a teacher who appreciated how useful a skill it is.

julie lee said,

January 1, 2014 @ 7:12 pm

Thank you for this post on sentence diagramming. I first learned parsing at age nine in an English school in India in the 1940s. I loved it. I also loved diagramming sentences. It later helped me understand long, complicated German sentences by diagramming them (mostly in my mind).

My grandson, here in California, was a great reader from the age of five. He read tons of fantasy novels and science-fiction novels before moving on to spy and suspense novels and other novels. A prolific reader (also of non-fiction). People say: "To be a good writer, the important thing is to read a lot." Because he was such a prolific reader from age five, I thought he would become a good writer, at least a writer of grammatical English. So I was very surprised to read his high-school compositions and find lots of grammatical errors. He was not expressing his thoughts well due to poor grammar. He was not writing well even though he was in a top high-school in Palo Alto, and getting A's for everything. I was shocked. I reported it to "the authorities" (his mother) and strongly recommended lessons in parts of speech and sentence-diagramming. I don't believe he had ever been taught how to diagram sentences. I think some action was taken by the authorities, and in his last year of high-school his writing had vastly improved and had become mostly grammatical.

julie lee said,

January 1, 2014 @ 7:24 pm

p.s. In my comment above, "recommended lessons in parts of speech" should have been "recommended lessons in parsing".

cameron said,

January 1, 2014 @ 9:11 pm

@Rod Johnson:

The 1900 work by Husserl that you're thinking of is his Logical Investigations. That section on parts and wholes is also hugely important in the subfield of mathematical logic known as mereology.

I would go so far as to claim that Husserl's early (pre explicit idealism) work is the best example of a structuralist philosophy.

Jeff Moore said,

January 1, 2014 @ 10:21 pm

Grammar teaching has gotten a seriously bad rap in language teaching over the last few decades, but more recent research is showing a place for form-based activities. I think there's real value in teaching students to diagram sentences, identify antecedents, and so on, even in a TESOL context. That doesn't mean it's the only thing they should be doing, though. It seems that when teachers advocating communicative language teaching see proposals for including some form of explicit instruction, they have visions of returning to a 19th-century grammar-translation model.

It doesn't necessarily have to be so! A quick 5- or 10-minute exercise in analyzing the grammar of a language can be a very nice Focus on Form activity, and can contribute to a lot of learning when paired with more communicative, task-based teaching. Grammar study can be a nutritious part of a complete balanced breakfast.

Rod Johnson said,

January 1, 2014 @ 11:31 pm

cameron: what… oh, I see, it somehow got changed to "Historical"–what the hell? I blame my phone. Believe me, I know my Logische Untersuchungen. I agree, the pre-phenomenological Husserl is clearly an important (and I think, overlooked) thread in European structuralism.

cameron said,

January 1, 2014 @ 11:51 pm

@Rod Johnson:

I think you mean pre-idealist, rather than pre-phenomenological. Pesky phone . . .

Derek said,

January 2, 2014 @ 12:25 am

I was taught sentence diagramming in the fifth and sixth grade around 2000 (in North Carolina), so it's definitely still around.

In hindsight, the idea was fine, but I wish that they had used a more modern method of sentence diagramming.

CThornett said,

January 2, 2014 @ 2:30 am

I was taught diagramming in fifth grade, in the mid-fifties. But because we were taught it as an end in itself, and not shown how it could be used to analyse the way the language works, it remained a dry and boring activity. For that matter, grammar lessons were generally dry, boring and disconnected from language use, mainly naming of parts and learning the shibboleths. I learned most at home or by having to rewrite and correct written work at school, and presumably picked up a good deal from reading.

Those were the good old days of 40 or more to a classroom and double shifts at times, which probably didn't facilitate more creative teaching.

Grammar teaching doesn't have to be like that, especially with the tools that devices can offer, but also by incorporating pattern-spotting and analysis. Current ESL/EFL teaching has a lot to offer in this regard.

Volkmar said,

January 2, 2014 @ 4:38 am

Here in South Africa I have never heard, seen or experienced this type of "sentence picture" – not at school nor ever thereafter. I think this is brilliantly easy for those kids struggling with languages – some struggle with Maths, others with Language.

GH said,

January 2, 2014 @ 7:19 am

As someone who was never taught sentence diagramming, I've read these proposals for its reintroduction into the curriculum with interest. However, I must admit that I haven't been totally convinced. Not to put too fine a point on it, but what's it good for?

My impression from the example here (and others I have looked up) is that it doesn't really express anything we don't already know as a matter of course if we understand the sentence (e.g. that "Our national" modifies "resources"), and conversely, that if we don't understand the sentence, it will be impossible to diagram it. From Wikipedia's basic introduction to Reed-Kellogg, it also seems as if it can only be applied to "full sentences", not all the other forms of statements found in normal discourse.

Granted that it might be useful grounding for budding linguists and people who will be developing parsers, but for the average student? Could someone provide an example of how it helps solve a problem, reveals something interesting/non-obvious, or teaches some useful principle?

I'm looking to be convinced here.

Luke said,

January 2, 2014 @ 8:34 am

I was born in 1988 in the UK, and can't remember studying anything like the tree diagrams you describe. Nor for that matter can I find any friend or acquaintance of my age who studied such diagrams, and I would be surprised to meet someone from the UK my age who did study tree diagrams. The grammar teaching at school I found largely confusing and questionable, relying on the descriptions of parts of speech often ridiculed by grammar I and (e.g, a verb was described as a doing word).

BlueLoom said,

January 2, 2014 @ 8:38 am

We were taught Reed-Kellogg sentence diagramming in our English classes every year from 7th grade through 12th grade in the DC public schools. A much sought-after class for seniors was Advanced Grammar & Comp (AGC). You had to have achieved at least a B in English the previous year in order to take this class–and even so a bunch of kids would drop the class after about the first week. In AGC, we had to write one essay per week (due every Friday), and we diagrammed sentences that sometimes ran all the way across the front blackboard and continued along the side blackboard. We loved it. It was treated as a wonderful and challenging puzzle that we worked together to solve.

I was terribly disappointed to find that, in my kids' high school classes in the 1970s, sentence diagramming was no longer taught. When I asked an English teacher why, he said, "We found that it didn't apply in all cases." Such a pity!

Ralph Hickok said,

January 2, 2014 @ 9:16 am

I learned to diagram sentences in the 4th grade in Wisconsin (1947-48 school year) and it remained part of the curriculum through 9th grade (for us, the last year of junior high school). High school English classes were devoted entirely to reading and writing.

Alexander said,

January 2, 2014 @ 9:29 am

@RodJohnson @Cameron

Husserl's "Logical Investigations" was also the background for what we now call the Categorial Grammar in Ajdukiewicz 1935, who was developing Lesniewski's development of Husserl. The idea was to make sure that any syntactically well-formed formula also had "a unified meaning", so as to avoid bad stuff like Russell's paradox.

wally said,

January 2, 2014 @ 11:12 am

@GH "but what's it good for?"

As someone who remembers enjoying diagramming sentences in 7th and 8th grade, when learning grammar was not high on my list of lifes priorities, I would say it was a fun activity in which parts of grammar were learned almost as a by product.

As opposed to the alternative, which was likely a boring activity in which not much at all was learned.

Andrew Bay said,

January 2, 2014 @ 12:01 pm

I remember doing something like this in the 90s in my pre AP/IB English class in highschool. I had been programming computers for a number of years prior so it kind of melded my English/Computer syntax processor into one thing. It was quite an "Andyism" when I told my wife that something she said contained a "Syntax Error." Her English degree hadn't prepared her for a common computer programming error message to be applied to English.

It may be interesting to compare how Oracle describes the database command syntax and how they graph them: http://docs.oracle.com/cd/B19306_01/server.102/b14200/ap_syntx001.htm#i631602

Theodore said,

January 2, 2014 @ 12:16 pm

It's a shame that the first-linked online parser (from 1AiWay) is limited to tweet-sized sentences. It seems intended for a young audience. It seems a school-age kid's first instinct (and still mine) will be to feed something Reznor-prize-worthy into it to see what happens.

e.heino said,

January 2, 2014 @ 1:05 pm

I might be a a minority among the readers of Language Log, but I did not like diagramming sentences in school (in the late 70s and 80s). It was a mechanical repetition of something I picked up intuitively from reading, and felt like a waste of time. I think it's actually more useful as an exercise in computer language, really, as it demonstrates how to break down complex concepts into objects and related properties in a hierarchy.

From my adult perspective, I think the issue is that like every educational tool (in the US at least), it was misused and applied too broadly. It's something that's worth teaching once, and then applying when people are having trouble reading or writing because of mangled or complex syntax. Some people will find it useful, and others will not.

Sybil said,

January 2, 2014 @ 4:19 pm

I learned sentence diagramming in the 60's, in 5th or 6th grade, and as some others have reported here, I found that it made grammatical analysis more fun. Don't know if I would call myself a visual learner, but I tend to translate abstract relationships into spatial relationships as a general rule, so I liked it.

I now often wish my (statistics) students understood how to diagram sentences, or SOME form of grammatical analysis anyway, for example when we have to distinguish conditional probabilities from probabilities of intersections (which can be remarkably tricky for them, particularly if they are oriented to looking for "key words" rather than meaning).

peterv said,

January 2, 2014 @ 5:06 pm

I'm not convinced at all that sentence diagramming is as easy for children as people seem to think, or indeed recall. For most people, it would require co-ordinated use of both brain hemispheres – one side for language and the other side for images. Activities which require hemispheric co-ordination are notoriously harder to do and to learn than activities which require use of only one side of the brain. Adults who have mastered this co-ordination are not best placed IMHO to say how easy or hard the activity is for children doing it for the first time.

And, moreover, I guarantee that we readers of LanguageLog, whatever other superb attributes we possess, were not typical of our school populations as a whole. So the whole activity of sentence-diagramming may have been much easier for us to do (for those who learnt it at school) than for our former classmates not currently reading this.

Rod Johnson said,

January 3, 2014 @ 1:32 am

Cameron: no, I meant pre-phenomenological. Husserl considered LI as a transitional work, with only the last two investigations being properly phenomenological. He took Ideas as the true starting point of his phenomenology, and characterized LI as "dirty work" he had to go through before he could begin phenomenology.

I think LI V and VI had almost no impact outside philosophy, whereas the analyses of signs, parts and wholes, and logic in I–IV stimulated all kinds of work in other disciplines, in logic with Lesniewski and Adjukiewicz, as Alexander points out above, in psychology with Ingarden and Buhler, and via the Prague Circle and Jakobson in linguistics and anthropology.

Auros said,

January 3, 2014 @ 2:51 am

No mention of Chomsky, deep grammar, etc? In the linguistics department I was taught in, when you built up the tree structure of a sentence, you often ended up with quite a lot of nodes that didn't correspond to words at all, but to things like the inflectional characteristics of them, or inferred pronouns (in pro-drop languages), and so on…

Richard Hudson said,

January 3, 2014 @ 4:03 am

Dick Hudson here again. Thanks everyone for your fascinating comments. I sympathize with those who complained that they did diagramming, but found it boring and pointless. The basic problem, in my opinion, is that it was so divorced from anything happening in universities that teachers had no academic underpinnings for it. Imagine maths where teachers were simply teaching what they themselves were taught in primary school, without having taken the subject to a higher level. Some teachers were clearly brilliant and inspiring; but others were struggling. That's what happened in other kinds of grammar teaching in the anglophone world, and the result was that it died.

What's it good for? Well, we now know that focused grammar teaching is actually good for writing (thanks to research by Bryant and Myhill). And for reading (Chipere). And for foreign languages (many researchers). For more, see http://teach-grammar.com/. Who knows – maybe it's good for 'thinking skills' too?

Tedankhamen said,

January 3, 2014 @ 6:41 am

I learned Max Morenberg style sentence diagramming during my undergrad (1996), and it has been invaluable to my career as a successful language teacher (Latin, French, English and Japanese) in Canada and Japan, at level ranging from primary to university. I don't think I would have gotten much use of it at a younger age, but as a young adult it helped me visualize grammar in a way that made sense, and that carried across the three languages I am fluent in. I don't think schoolkids necessarily need it, but it is a great exercise for adults to go back and understand the moving parts of the language they speak naturally, or even to understand second languages and have a working grasp of the technical terms of grammar.

John said,

January 3, 2014 @ 12:04 pm

As a Latin teacher, I can guarantee that most students have zero clue about English grammar now. Teaching grammar explicitly makes learning other languages a lot easier, as well as improves students' writing abilities. The Sentence Diagram is simply a tool to make grammar more understandable :)

marie-lucie said,

January 4, 2014 @ 12:29 pm

John: As a Latin teacher, I can guarantee that most students have zero clue about English grammar now.

As a former French and Spanish teacher, I could say the same, replacing Latin with French, Spanish, etc. One publisher (I forget which one) puts out a series of small books called English grammar for students of [relevant foreign language], which are specifically geared towards those students who have hardly ever been taught any kind of English grammar (except perhaps for the usual warnings about splitting infinitives and the like), or if they have, few of them have more than a nebulous understanding of what the parts of speech are, let alone types of clauses, etc. It is not the students' fault, or even their former English teachers', most of whom seem to have parroted things they were themselves taught, without quite understanding them.

Federico Gobbo said,

January 4, 2014 @ 3:09 pm

Thank you for this great post. I wasn't aware of this US tradition, I worked out the Tesnièrian stemmas resulting in the Cobstrictive Adpositional Grammar paradigm. Certainly I will delve into Stephen Watkins Clarck figure in the next future.

Dominik Lukes (@techczech) said,

January 6, 2014 @ 4:12 am

A bit late to the party. I was inspired by this series of posts to write a rebuttal on http://metaphorhacker.net/2014/01/5-things-everybody-should-know-about-language-outline-of-linguistics-contribution-to-the-liberal-arts-curriculum/.

I don't think that the case for introducing diagramming or any grammar instruction to the school curriculum has been made – not that there's anything hugely wrong with it but I propose that there are many more things that should be taught about language before we even start on this.

I am a product of the Czech approach (during its heydey) and while it made it somewhat easier for me to start studying linguistics, it made no difference to my cohort. Most of my peers hated it, found it a struggle and no help at all in any other language arts. So if you absolutely must, give students a taste in one or two lessons of the very most basic dependencies (or constituents) but don't drag it out. It's painful and self-indulgent.

William Stewart said,

January 6, 2014 @ 5:50 pm

Diagramming sentences was taught in the 50s in Lexington, Kentucky. In the eighth grade we were also taught the principal parts of verbs and also the "future perfect progressive"; an example of which occurs in the sentence "I shall have been being seen."

Sandra Wilde said,

January 11, 2014 @ 8:21 am

There's no good reason to teach diagramming or other linguistic analysis in k-12 education. The National Council of Teachers of English has a position against it. I've written a whole book about the appropriate role of linguistic study for kids, Funner Grammar.