Nurses say yes and no

« previous post | next post »

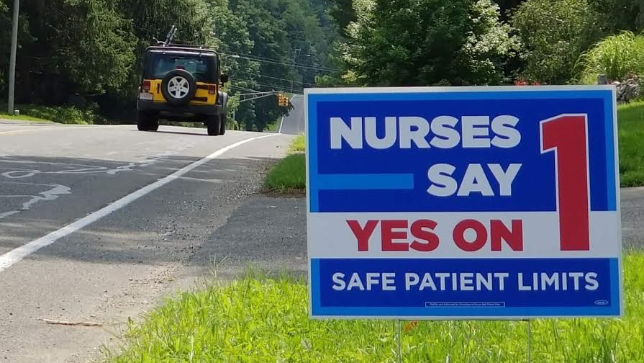

Question #1 on this November’s ballot in Massachusetts concerns a proposed law

to limit the number of patients that can be assigned to a nurse at any one time.

More than $15 million dollars have already been spent on campaigning about this

question. Lawn signs on both sides of the debate abound in the state:

Now, inquiring minds might wonder: what is it, do nurses say yes or do they say

no?

The grammatical construction used by the signs is known in linguistics as a

“bare plural”. The plural is “bare” in that it doesn’t come with any determiners

or quantifiers (such as “most nurses”, “some nurses”, and so on).

Each sign read on its own invites an interpretation like “nurses, in general,

say yes/no”. This is called the “generic” or “quasi-universal” interpretation in

semantic studies on bare plurals. When read generically, the two signs

contradict each other: they can’t both be true, can they? So, should one of the

campaigns be investigated for making a false claim (as if that’s a problem these

days)?

But conveniently, English bare plurals have another interpretation, called

“existential” in the semantics trade. So, when I say that rabbits ate my lettuce

plants, I’m not saying that rabbits in general ate my lettuce. Instead, the

claim is that some rabbits did it. If the bare plural “nurses” on the signs is

read existentially, the claims are not in conflict. Some nurses say yes, some

say no, big deal.

Are the signs intended to be read existentially? Of course not. Surely, it would

be surprising to find lawn signs that say “some nurses say yes”. That doesn’t

seem like a convincing argument for a yes-vote.

So, what’s going on? The inherent ambiguity or underspecificity of bare plurals

allows the campaigners to convey strong claims but to have plausible deniability

if ever challenged on those claims. One sometimes hears that the fact that

language is ambiguous, vague, and context-dependent is some kind of flaw. But

clearly, these properties are very useful as well, not least for clever

campaigners. Making the addressees come up with the intended interpretation

without specifically committing to it is a splendid way of saying one thing

while maybe not really saying it.

[Update:] As pointed out to me by Michelle Yuan, another aspect of these signs is rooted in the essentialist signal sent by generic bare plurals. By saying “nurses say yes/no”, what each side is actually claiming is that real nurses say yes/no. It would be much closer to the truth if the signs said “management nurses say no” and “union nurses say yes”, but even that is of course an oversimplification. The very problematic essentialism often inherent in bare plural statements is also something that Mark Liberman mentions in his follow-up post, with many more references.

Further reading: