Language and politics in an Inner Mongolian post office

« previous post | next post »

[This is a guest post by Bathrobe.]

Recently I travelled in Inner Mongolia (China) where I picked up a few books in Chinese, Mongolian (traditional script), and English. As the books were getting heavy, I decided to offload them by posting them to Beijing for later pick up.

The lady at the post office was very apologetic, but they had just the day before received strong instructions to look out for books about Mao Tse-tung or the Cultural Revolution. They could accept only books written in Chinese characters; any others would first require clearance from the local office of the Bureau of Cultural Affairs.

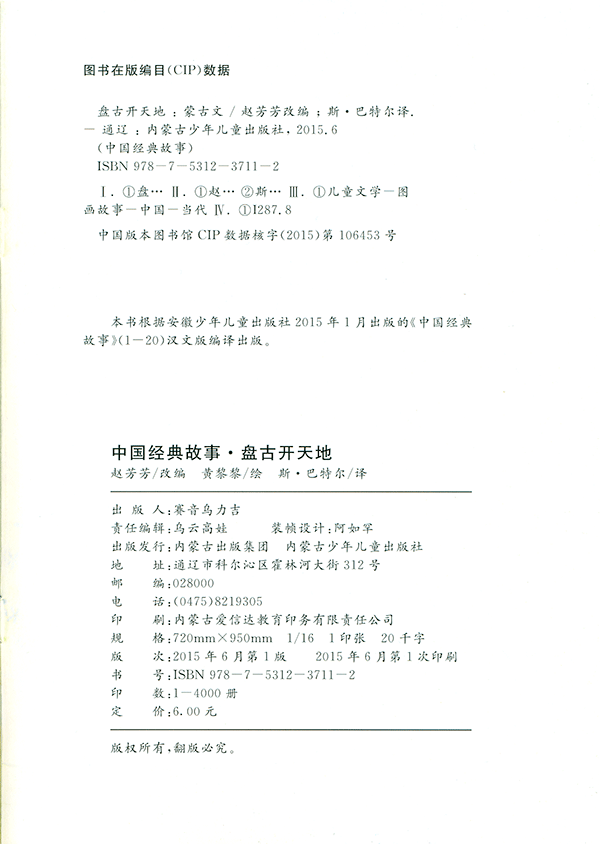

I pointed out that some of my Mongolian-language books were illustrated children’s books of Chinese mythology with only short stretches of text. I showed her one of the books, which was about the myth of Pangu. The picture was assuredly not of Mao Tse-Tung. And like all Mongolian-language books published in Inner Mongolia, there was a page in Chinese at the back showing the book’s title and publication details. After consulting with her supervisor, the lady was very sorry, but since it was not in Chinese characters she could not send the book without a certificate of clearance.

I also had a book by the 19th-century novelist Injinash. Unfortunately this was in three volumes and publication details for all three were only in the first volume. If an illustrated book couldn’t be posted, the novel didn’t stand a chance.

Since time was short I decided to send only the Chinese books.

But this little episode brought home how abnormal the atmosphere is becoming in China. This was a book published in the Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region, in the language of that region. The post office was in an Inner Mongolian city. The book was obviously not about Mao or the Cultural Revolution. But I could not post it without special clearance.

This absurd situation was caused by an accumulation of factors:

- Security officials are not noted for their subtlety or respect for minorities. Niceties are easily brushed aside when “national security” is at stake. If Han Chinese can’t read it, it needs special clearance; to hell with minorities.

- The books were being sent to Beijing, a politically sensitive city.

- Bureaucrats are notoriously cautious. Neither the lady nor her superior was willing to risk doing the wrong thing. Refusal was the safest option.

- Although it was located in the Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region, the post office did not appear to have staff competent in Mongolian. Presumably people in Inner Mongolia long ago abandoned the practice of addressing letters in Mongolian, out of exasperation. (Of course, it is moot whether even a Mongolian-speaking staff member would have been able to authorise the books.)

Whatever the cause, it is inconceivable in most countries that books published in that country could not be sent by post without special clearance.

I entertain little hope that the Chinese security authorities could be shamed into modifying their methods. They are not afraid of being described as heavy-handed since that is their job. Nor are they likely to be shamed by ridicule if they sincerely believe that someone might go to the expense of printing information about the Cultural Revolution concealed inside a children’s book.

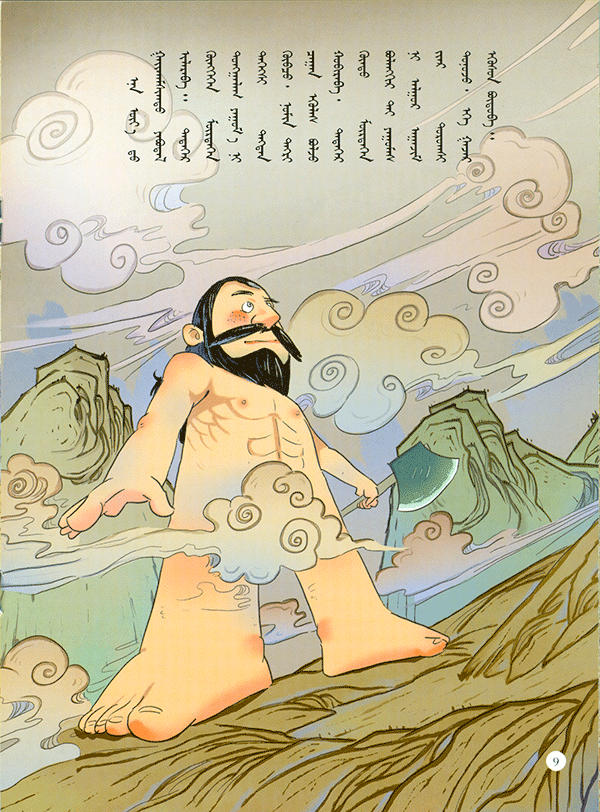

Illustrations

Pangu, the mythical first living being:

Publication data for the children's book about Pangu:

Anschel Schaffer-Cohen said,

July 22, 2018 @ 4:47 pm

> it is inconceivable in most countries that books published in that country could not be sent by post without special clearance.

This was in fact the case in the United States for many decades under the Comstock Laws.

Jichang Lulu said,

July 22, 2018 @ 5:15 pm

The Mongolian text describes the separation of heaven and earth in the Pangu 盘古 myth: the light, clear things floated up, turning into the white clouds and the azure sky, and the heavy, thick stuff gradually sunk, forming the earth. (In the Sanwu liji 三五历记 locus classicus: 阳清为天,阴浊为地 Yáng qīng wéi tiān, yīn zhuó wéi dì.) Hardly seditious content.

It's quite ironic that censorial zeal could actually complicate the propagation of materials teaching Han culture to the non-Han, a goal of PRC minority education. And, as Bathrobe says, it only adds insult to injury that no Mongolian-language service is available in a nominally bilingual ‘Autonomous’ Region.

Here's hope Bathrobe can at least keep some of these seemingly delightful books.

Lihua Fu said,

July 22, 2018 @ 5:18 pm

Inner Mongolian is indeed an autonomous region, which means most Mongolian as one of the minorities in China are located in Inner Mongolia. However, there are other minorities and Han as well in this autonomous region. Therefore, Mongolian is not taught at every school. There are schools teaching in Mongolian, but they co-exist with the standard schools very well. As far as the language is concerned, the official language is Mandarin. Mongolian is one of the factors showing the multi-faceted culture in China.

Victor Mair said,

July 22, 2018 @ 6:29 pm

From Wikipedia:

The Comstock Laws were a set of federal acts passed by the United States Congress under the Grant administration along with related state laws. The "parent" act (Sect. 211) was passed on March 3, 1873, as the Act for the "Suppression of Trade in, and Circulation of, Obscene Literature and Articles of Immoral Use". This Act criminalized usage of the U.S. Postal Service to send any of the following items:

obscenity

contraceptives

abortifacients

sex toys

personal letters with any sexual content or information

or any information regarding the above items.

A similar federal act (Sect. 245) of 1909 applied to delivery by interstate "express" or any other common carrier (such as railroad, instead of delivery by the U.S. Postal Service).

In Washington, D.C., where the federal government had direct jurisdiction, another Comstock act (Sect. 312) also made it illegal (punishable by up to 5 years at hard labor), to sell, lend, or give away any "obscene" publication, or article used for contraception or abortion. Section 305 of the Tariff Act of 1922 forbade the importation of any contraceptive information or means.

In addition to these federal laws, about half of the states enacted laws related to the federal Comstock laws. These state laws are considered by Dennett to also be "Comstock laws".

The laws were named after its chief proponent, Anthony Comstock. Comstock received a commission from the Postmaster General to serve as a special agent for the U.S. Postal Service.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comstock_laws

Bathrobe said,

July 22, 2018 @ 7:27 pm

@ Lihua Fu

Inner Mongolian is indeed an autonomous region, which means most Mongolian as one of the minorities in China are located in Inner Mongolia.

If Wikipedia is to be believed, the Chinese constitution disagrees with your simple characterisation:

'Autonomous regions, prefectures, counties, and banners are covered under Section 6 of Chapter 3 (Articles 111-122) of the Constitution of the People's Republic of China, and with more detail under the Law of the People's Republic of China on Regional National Autonomy (《中华人民共和国民族区域自治法》). The constitution states that the head of government of each autonomous areas must be of the ethnic group as specified by the autonomous area (Tibetan, Uyghur, etc.). The constitution also guarantees a range of rights including: independence of finance, independence of economic planning, independence of arts, science and culture, organization of local police, and use of local language. In addition, the head of government of each autonomous region is known as a "chairman", unlike provinces, where they are known as "governors".'

Joshua K. said,

July 22, 2018 @ 7:46 pm

What is the current political "line" on the Cultural Revolution that the Chinese government wants to promulgate?

Jonathan Badger said,

July 22, 2018 @ 7:59 pm

@Victor Mair

Just to be clear, while the *intent* of the Comstock Laws may be have been to stop posting of pornography and contraception materials, in practice they were applied as arbitarily as your experience with the Chinese laws. They were applied to shop shipment of great literature by Hemingway, Chaucer, and Joyce, among other authors.

http://www.wiki.ncac.org/Comstock_Law_Book_Banning_in_U.S.

Bathrobe said,

July 22, 2018 @ 8:19 pm

@ Jichang Lulu

Yes I kept the books. They are not against the law. The problem is that they can't be sent through the post without certification because people like the lady at the post office and presumably censors who open the package en route can only read Chinese. One wonders why they can't trust the publication details in Chinese, which appear to be a legal requirement.

I bought the books precisely because they teach stories of the mainstream culture to ethnic minorities. Others included Nü Wa mends the heavens, Cao Chong weighs an elephant, Mr Dongguo and the wolf (which depicts the wolf in a very different way from Mongolian attitudes; the wolf as portrayed in the story is a cunning and ungrateful creature, whereas the Mongols see the wolf as an animal to be respected and feared, not as a sly, sophistic, ingrate), Kong Rong shares his pears, Sima Guang breaks the jar, and the lotus lamp (宝莲灯).

There were also books with Chinese and Mongolian in parallel, which I was able to send. These included Destroying opium at Humen, Chang E escapes to the moon, Ma Liang and his magical writing brush, the Eight Immortals cross the sea, and Mao Sui volunteers his services (the source of a well-known proverb in Chinese).

The most interesting was called "Silk Road", which told how Zhang Qian of the Western Han kept the Silk Road open against the depredations of the nasty Xiongnu, allowing Chinese merchants to sell silk to the West for huge profits (shades of One Belt One Road). I guess the Xiongnu aren't covered by the Zhonghua Minzu ideology. In Mongolia, people are taught that the Xiongnu are their ancestors.

In one bookshop in the same city I noticed Chinese-language illustrated books about Genghis Khan relegated to the tiny Mongolian-language corner. When I asked why, I was told Han children weren't interested in them. So much for the 'multi-faceted culture in China'.

Bathrobe said,

July 22, 2018 @ 8:39 pm

What is the current political "line" on the Cultural Revolution that the Chinese government wants to promulgate?

I am not qualified to even guess why this is so sensitive. Perhaps it is part of the running battle between the current leader and his detractors in the populace, in a similar vein to the crackdown on Winnie the Pooh. But there might be political undercurrents that outsiders have no way of knowing.

Victor Mair said,

July 22, 2018 @ 9:25 pm

Several people have asked me the related question of why postal authorities are being so cautious about Mao. I replied:

=====

My surmises:

1. so as not to compare Xi with him

2. so that his memory will not compete with or diminish Xi as the ultimate, paramount leader for today

3. it seems that some members of the CCP have finally begun to realize that Mao has a horrible reputation outside of China, and that now even a considerable number of Chinese citizens within China have come to understand what a terrible disaster he was for China

I base these surmises on things I'm hearing from PRC citizens.

=====

J.W. Brewer said,

July 22, 2018 @ 10:30 pm

It is interesting (and perhaps a silver lining of sorts) that this means that the PRC authorities are not so confident in the rigor and perfection of their prior system of censorship of Mongol-language books published in Inner Mongolia (I'm assuming from the original post that there are indicia in Mandarin re place/date of publication so you can tell they're not unapproved texts smuggled across the border) as to assume that anything that was safe enough to be published is safe enough to be mailed. Or perhaps it just means that what they are and are not concerned about changes over time and that a book was uncontroversial enough to be allowed to be published 10 years ago doesn't mean it's guaranteed to be trouble-free now, as the Beijing regime's priorities and context may have shifted.

Bruce Humes said,

July 22, 2018 @ 10:51 pm

Re: the "current political 'line' on the Cultural Revolution that the Chinese government wants to promulgate"?

I'm no expert on the Party's latest politically correct narrative concerning the Cultural Revolution. But I would point out:

*** I've written articles for The China Daily in which the editor insisted on putting mentions of "Cultural Revolution" in quotes. To me, this implies that it is being treated as a "so-called" phenomenon; i.e., it may or may not have happened, and its perceived excesses may or may not be based on fact.

*** If one reads almost any account of any non-Han artist — writer, storyteller, musician — specializing in the culture of his ethnicity, one very quickly notes that the period of the Cultural Revolution (1966-76) is almost always entirely missing; the text inevitably skips from about 1962-1978, as if nothing happened during that period. One example is Jusup Mamay, the recently deceased reciter of the Kyrgyz epic, "Manas". In fact, many of these artists — including him — were publicly criticized as separatists and right-wingers, and sentenced to forced labor, etc.

As far as I know, this policy of enforced amnesia continues under the illustrious new emperor.

艾力·黑膠 said,

July 23, 2018 @ 12:17 am

I would think that unlikely, given that Cyrillic is used for almost all texts in (Outer) Mongolia, which most ethnic Mongolian PRC citizens cannot read.

ajay said,

July 23, 2018 @ 3:48 am

the text inevitably skips from about 1962-1978, as if nothing happened during that period.

"The Church is never wrong," as one cardinal said a few years ago during the exoneration of Galileo, "but it may move from one position of certainty to another".

David Marjanović said,

July 23, 2018 @ 5:09 am

Sure, but it doesn't take extreme amounts of paranoia (just medium ones!) to imagine that irredentists in Mongolia would print books in the Mongolian script, which is taught there in the later years of school and used for ornamental purposes, and smuggle them into China to disrupt peace & harmony.

Bathrobe said,

July 23, 2018 @ 5:48 am

I should point out that the requirement for certification appears to apply to all books not in Chinese, not just minority languages. I had to go through the same process to send a foreign language textbook (with no Chinese in it) last year.

What struck me is that the security leadership (who are, of course, Han Chinese) are so cavalier about the right of autonomous regions to use their own language. It seems to me typical of the attitude of the government to "autonomy". Ethnic minorities are made into foreigners in their own country.

J.W. Brewer said,

July 23, 2018 @ 7:10 am

My point was just expanding from the original post's statement "And like all Mongolian-language books published in Inner Mongolia, there was a page in Chinese at the back showing the book’s title and publication details." It would be one thing for the postal employees to refuse to handle books in a script unknown to them whose time and place of publication was unknown to them and thus might not have been under PRC auspices, but you'd think that that legible-to-MSM-readers page would have served as the equivalent of an imprimitur/nihil obstat indicating that the original publication had been sufficiently blessed by the PRC censorship authorities. One wonders if they would refuse to handle books written in Mandarin but typeset in traditional characters, which ought to suggest the possibility that they might have been printed pre-1949, or in Taiwan, or some other possibly threatening time or location.

Janet Upton said,

July 23, 2018 @ 9:48 am

Back in the mid-late 1990s and early 2000s, my husband and I shipped a lot of Tibetan- and Mongolian- language materials both within and out of China. At that time, the only requirement that seemed to be consistently enforced, for both domestic and international shipments, was that materials have ISBN numbers. At that time the practice of printing anything even moderately sensitive with the "internal reference" (neibu ziliao) label was still widespread, so anything with that on it could not be shipped even if it had an ISBN.

I do remember things getting scrutinized much more closely in Chengdu than in Xining. But since the content label is there in Chinese for all minority language books, that usually solved the problem.

JK said,

July 23, 2018 @ 3:49 pm

I'm guessing this is a nationwide expansion of the policy that started somewhat recently in Xinjiang of not allowing any non-Chinese materials to be sent by mail for "security" reasons. Its also an extension of the move from education and everyday business being allowed to occur in minority languages to only having one officially-recognized "national common language," which all minority languages are secondary to.

Victor Mair said,

July 23, 2018 @ 5:03 pm

From a Mongolian graduate student:

Wow, this is disturbing! Only a few years ago (10+? I forget), Mongolians of IMAR protested the fact that they weren’t allowed to send letters addressed in Mongolian through the postal system by flooding the local post offices with letters and postcards addressed in Mongolian. If I remember correctly, the PRC responded by declaring that more Mongolians shall be hired in the postal system to allow the Inner Mongolians to practice their constitutional rights… So it was considered a victory for the protestors!

jdmartinsen said,

July 23, 2018 @ 8:10 pm

@Bruce Humes: The quotes around Cultural Revolution date from the early 80s, when the party was deliberating its verdict on the period, and serve to deny not the movement itself but its relationship to "culture" and "revolution." Since, in the words of the 1981 resolution, the Cultural Revolution "did not in fact constitute a revolution or social progress in any sense" (translation from FLP via Marxists.org) some people felt the term should be rejected as a relic of a repudiated extremist movement. Secretary-General Hu Yaobang was apparently the first to propose quote marks in a speech in mid-1980: "Just put it in quotes, since it is after all part of history, a historical interlude."

Victor Mair said,

July 23, 2018 @ 9:40 pm

From Paul Mooney:

The world gets little news about what’s going on in China’s “Inner" Mongolia, but the people there suffer too, albeit not as much as the Tibetans and Uyghurs. The Mongolians living in Inner Mongolia are second class citizens and their culture is on the verge of extinction. I get frequent newsletters from The Southern Mongolia Human Rights Information Center based in New York that highlight human rights abuses in what they refer to as Southern Mongolia, refusing to recognize that their homeland is a legal part of China. I’ll post things from time to time from this organization to keep people aware of what the Chinese are doing in this somewhat forgotten part of the world.

Victor Mair said,

July 23, 2018 @ 9:41 pm

From Juha Janhunen:

I fully agree, except that I think that "human rights" is a term of North

American liberals not applicable to the situation in Inner Mongolia. In my opinion it is a question of ethnic, linguistic, territorial, and political rights. China – on paper also the Republic of China – is simply occupying neighbouring countries, including Tibet, East Turkestan and parts of Mongolia. With time, the Chinese also look forward to getting Outer Mongolia, whose independence has until now been saved by Russia. – jj (from Komsomolsk-on-Amoor)

liuyao said,

July 23, 2018 @ 10:07 pm

@Bathrobe

Thanks for the detailed description of the contents. They are the exact sort of (Han) Chinese stories that we grew up with (in PRC).

Bathrobe said,

July 23, 2018 @ 11:22 pm

What is taking place in areas like Inner Mongolia, Tibet, and Xinjiang represents a playing out of the legacy of the Qing. The issues involved are perennially contentious ones since these territories were a part of the Qing without necessarily being a part of "China proper" (about which a great deal of hair-splitting is possible).

But I don't think that speaking in terms of "occupying neighbouring countries" is a productive approach. Faced with lingering claims that they are really separate countries, the Chinese are only going to feel more determined to completely digest them and put to rest any claims about "countries".

At any rate, whatever view you might take, it is unrealistic to expect that the Han Chinese, who make up over 80% of the population of Inner Mongolia, either could or should be expelled from the region — a horrendous and inhumane prospect that is tantamount to 'ethnic cleansing'.

What is at stake is whether China can keep its commitment to guarantee the independence of culture and use of local languages in these territories, which have backgrounds that are in many ways different from mainstream Chinese culture. Recent governments, whether from considerations of 'national consolidation' or from convictions of the supremacy of the mainstream culture, have not been doing this. It should be possible to say 'I am Mongol and Chinese' or 'I am Tibetan and Chinese', etc. without losing one's native culture. The Chinese authorities don't appear to believe this. According to their way of thinking there is only one kind of Chinese: a person who is completely assimilated to the mainstream language and culture, effectively a 'Han Chinese'. There are no acceptable alternatives. That appears to be behind the Chinese government's current push to make these areas completely 'Chinese'. The little post-office drama is just one manifestation of the way in which the Chinese government is ever so slowly but surely moving towards this.

Philip Taylor said,

July 24, 2018 @ 4:16 am

Bathrobe : 'I am Mongol and Chinese' or 'I am Tibetan and Chinese'. Would you not agree that one should also be able to say 'I am Mongol; I am not Chinese' or 'I am Tibetan; I am not Chinese' without fear of persecution or penalty if that is one's true self-identity ?

Bathrobe said,

July 24, 2018 @ 4:57 am

'I am Tibetan; I am not Chinese' 'I am Mongol; I am not Chinese' — dangerous ground.

Nation-states are extremely jealous of the loyalty of their citizens. In this case the problem might simply be that 'Chinese' is an unsuitable word, historically and semantically, for 'citizen of the PRC', as we have discussed previously. But nation states are in trouble when people start saying things like 'I am Kurdish; I am not Iraqi', 'I am Catalan; I am not Spanish', 'I am (northern) Irish; I am not British', 'I am Quebecois, I am not Canadian'. China is more jealous than most.

The failure of citizens to identify with the state they belong to can lead to issues of disloyalty and betrayal. In Mongolia, some Kazakh-ethnic members of the Mongolian parliament were later found to be passing state secrets to the government of Kazakhstan. This is treasonous behaviour and would not be tolerated by any state.

China is arguably plagued by deeper problems than most. In Tibet and Xinjiang, the Chinese have decided that the only solution is the use of armed force and police-state tactics. China's 'final solution', swamping territories with Han Chinese and cutting off local cultures at the root through the education system, is actually an admission of failure. They have failed to gain the peaceable and open allegiance of these people. I am sure that there is plenty of room for debate over the roots of this failure, but I would argue that it lies in the nature of Chinese concepts of 'sovereignty' over people, the model of ethnic relations it has adopted (anyone but the Han Chinese is just a 'minority'), the nature of the Chinese political system, deep-seated cultural attitudes among the Han Chinese, and long-term dishonesty in dealing with minority ethnic groups.

loonquawl said,

July 24, 2018 @ 5:26 am

Are there any english-language publications that serve as an omnibus for the stories and myths that were referenced in @Bathrobe s comments?

Ricardo said,

July 24, 2018 @ 5:55 am

Depending on how you see the matter, the attitude of the post-office occupies a place somewhere along the spectrum between culturally insensitive and draconian. But in the age of ebooks and other forms of electronic transmission, I wonder whether it amounts to much more than an inconvenience to the scholar or afficionado who wants the physical book. And if he is desperate to have the book, someone could simply carry it for him as happens all the time with books from Hong Kong.

J.W. Brewer said,

July 24, 2018 @ 9:59 am

To bathrobe's point, I am pretty sure my in-laws self-identify as both Taiwanese and Chinese and do not feel the need to define their Taiwanese identity contrastively as non-Chinese. On the other hand, their political views are very much on the "green" side in the context of current Taiwanese political opinion, so that they do not think "wanting Taiwan to be ruled by the same government that is in power on the mainland" is any sort of natural logical consequence of self-identification as "Chinese" — for them it would perhaps be more like someone self-identifying as both Singaporean and Chinese. I assume that from a PRC perspective any sense of Chinese/Han self-identity that is consistent with "splittist" political opinions is not the sort of identity that they're looking to promote.

To bathrobe's broader point about the Communists' desire to cling to the Qing dynasty's conquests (although maybe I should call them the Cing or Tshing dynasty, just to score a point for the Taiwanese?), the downfall of Communist power in Moscow led to the loss of many, but not all, of the Romanov conquests the Communists had been happy to inherit from the prior regime (and some of which they had reconquered for themselves in 1945 after being unable to retain them in the immediate aftermath of 1917). Whether an eventual downfall of Communist power in Peking might have similar consequence gets us to the proverb that it is difficult to make predictions, especially about the future.

Victor Mair said,

July 24, 2018 @ 12:42 pm

"China Holds Ethnic Mongolian Historian Who Wrote 'Genocide' Book"

RFA 2018-07-23

https://www.rfa.org/english/news/china/mongolian-historian-07232018123931.html

David Marjanović said,

July 24, 2018 @ 5:02 pm

Applicable to the situation or not, I'd like to point out that "human rights" is a term common to the entire West at the very least, with the notable exception of US "conservatives".

(Scare quotes because, among several other reasons, their economic policies are extremely liberal. But I digress from the digression.)

Bathrobe said,

July 24, 2018 @ 7:44 pm

The Cultural Revolution was a period of excess throughout China. However, it was devastating for Inner Mongolia because of the ethnic factor. In 1968, a witch-hunt to root out the "New Inner Mongolian People’s Party", which allegedly aimed to reunite with Mongolia, caused the death of 16,000 people (another figure is 22,000) at the hands of the PLA, as well as the injuring of 340,000. The villain of the piece was one 滕海清 Téng Hǎiqīng, a PLA general hailing from Anhui province who had become chairman of the autonomous region, displacing Ulanfu, an ethnic Mongol. The campaign was so fierce that Mao issued a directive in May 1969 that the political campaign had got out of hand.

This is an episode that the Party would prefer to forget. On the Internet, biographies of Teng Haiqing (including that at Wikipedia) are brief and omit any mention of his activities as Chairman of Inner Mongolia.

But history refuses to lie down, as people like Lhamjab and others continue to probe what happened. Lhamjab's "crime" is putting a spotlight on something that is supposed to be forgotten.

On the other hand, there appears to be certain strain of thinking inside China that approves of what Teng did. A particularly vicious and threatening piece hailing Teng Haiqing as a hero who rooted out the Mongolian independence group appeared at the 加拿大华人论坛 (BBS of Chinese in Canada) in 2011, a few months after demonstrations over the killing of an Inner Mongolian herdsman by a Han coal truck driver. The piece was still there in 2016 but has since been taken down. (It also appeared elsewhere but is no longer available.)

This particular episode provides a good illustration of why the Party is so sensitive about keeping history under wraps. Focusing on history detracts from its authority and distracts from the grand narrative of progress and improvement, including the Belt and Road initiative.

Ken said,

July 24, 2018 @ 9:22 pm

Bathrobe:

I must be a natural subversive, because I immediately thought of printing books with innocuous Chinese text for the post office censors to read, paralleling Mongolian text that said something quite different.

Bathrobe said,

July 24, 2018 @ 10:02 pm

Post office staff are very literal-minded.

Jim said,

July 25, 2018 @ 3:27 pm

There was a time about 10 (maybe 15) years back that many adult (mostly porn, other "mature audiences") comic books could not be sent from the US to Canada, getting seized by Customs. The irony being that the books were *printed* in Canada in the first place, then shipped to the US, and shipped from the distributor warehouse there.

Philip Taylor said,

July 26, 2018 @ 2:18 am

Bathrobe : " 'I am Kurdish; I am not Iraqi', 'I am Catalan; I am not Spanish', 'I am (northern) Irish; I am not British', 'I am Quebecois, I am not Canadian'. China is more jealous than most". Thank you very much for your insightful response. From a purely personal perspective, I would strongly support the right of a Kurd, a Catalonian, or an Irish person (from the North) to make the statements you suggest, but am less certain about the Québécois. This probably says far more about me and my views than it does about the facts of the case.

Philip Taylor said,

July 26, 2018 @ 2:27 am

P.S. What does surprise me is the number of highly-educated, intelligent and patriotic Canadians with whom I have spoken who assert "I am Canadian and I am American" (where the "and" is almost an ergo) — it seems to me as a Briton that while we (the British) tend to think of America (qua America, rather than "the Americas") as being synonymous with "the United States of America", Canadians (and perhaps Americans, in the British sense of the word) think of "America" as designating a continent, not as a country.

Ellen K. said,

July 26, 2018 @ 10:15 am

Not all Canadians. I've heard Canadians refer to "coming to America" meaning coming to the United States. Which I personally found strange, because, to me, "coming to America" would mean coming to the U.S. from outside the Americas. (Though I suppose it's also possible they use "American" and "America" differently. But different people using the terms differently seems more likely.)

Christian Weisgerber said,

July 26, 2018 @ 3:12 pm

@Philip Taylor

This is completely opposite to my experience where Canadians are very vocal that they are not "Americans" and it is very clear that in Canadian English "America" is synonymous with the USA.

richard said,

July 26, 2018 @ 4:25 pm

When I went to Indonesia in 1999 to begin roughly two years of field work in Minahasa, I also was preparing to go from there to either Japan or Korea (hadn't made up my mind yet…you know how it is.) So I brought with me materials to study both languages to keep my facility up and be ready to go either place. To bring them into the country I had to certify that they were not, in fact, in Chinese, as importing books in that language was, as they say, ganz verboten. This being Indonesia, signing a piece of paper that had nothing meaningful on it, and paying an "unscheduled fee," took care of the matter–but had I tried doing the same thing only two years earlier, life would have been far more difficult (and expensive). And I should say I have a number of friends who have been questioned coming back into the US with books in what looked like Arabic to the customs folks.

This is not to minimize Bathrobe's experience, but to observe some commonalities across the globe.

Bathrobe said,

July 26, 2018 @ 5:51 pm

@richard

That is a very interesting example. In Mongolia (the country), I don't believe there is a ban on using Chinese characters, but you will not find any Chinese restaurants in Mongolia with their names written in Chinese on the outside of the restaurant. Names are usually in Cyrillic. My understanding is that this is a result of the activities of a minority of diehard anti-Chinese nationalist vigilantes, who were particularly virulent in the past. Japanese restaurants are exempted, so you will find Chinese characters on the outside of Japanese restaurants.

(In the light of what we have discussed at other threads, it is also interesting that the Chinese government has been very concerned about the treatment of "ethnic Chinese" (read "Han Chinese") in places like Indonesia. By contrast, they do not appear to be at all concerned at the treatment of non-Han "Chinese" anywhere outside their borders, except in a negative sense, such as successfully stopping the teaching of Uyghur in universities in neighbouring countries of central Asia.)

Eidolon said,

July 26, 2018 @ 8:20 pm

@Philip Taylor @Bathrobe

> Would you not agree that one should also be able to say 'I am Mongol; I am not Chinese' or 'I am Tibetan; I am not Chinese' without fear of persecution or penalty if that is one's true self-identity ?

> Nation-states are extremely jealous of the loyalty of their citizens. In this case the problem might simply be that 'Chinese' is an unsuitable word, historically and semantically, for 'citizen of the PRC', as we have discussed previously. …

Excellent discussion, and I think both statements have merit. But I'd like to make a caveat about structuring the debate in terms of loyal Han vs. rebellious minorities. The Chinese government is just as sensitive to "subversion" from Han, in fact perhaps even more so, since they depend on Han to carry out their policies. Recent events, like the removal of term limits for Xi Jinping and the expansion of the state security apparatus, have been immensely unpopular among Han, so I wouldn't argue the Chinese government has a consistent track record of appealing to Han loyalty.

But the difference is that they can manage and control Han "subversion" directly – such as in the recent case of a woman who spilled ink on Xi Jinping's portrait in protest – because they can monitor the lines of communication between Han with relative ease, in spite of all the code words Han netizens use to trick the censors. Minorities and foreign nationals, by contrast, have linguistic channels the Chinese government are not privy to, except through translation – which is both more expensive and less reliable; consequently, they are treated with suspicion and extreme caution, as in this case where it has become illegal to mail books that cannot be read and validated by local bureaucrats.

This is also the reason I don't expect the Chinese government to approve or promote any additional Romanizations, scripts, or languages, regardless of the policy's potential benefits to affected minorities. Perhaps Han attitudes does play into it, as Bathrobe has argued in the past, but the security aspects are even more significant – a proliferation of scripts and languages in China would make monitoring the lines of communication exponentially more difficult. At least, until machine translation becomes sufficiently mature that they could monitor all languages at the same time.

Bathrobe said,

July 26, 2018 @ 9:12 pm

I don't see the issue in terms of loyal Han vs rebellious ethnics and I haven't presented it as such. I see it as a form of cultural discrimination against a segment of their own citizenry.

I can only speculate why the Chinese government should be concerned about Mao and the Cultural Revolution. They presumably have their reasons. But the insistence on Chinese characters (汉字) is inherently discriminatory. (As an aside, I wonder how they would treat Japanese books.) Why not allow for the Chinese-language publication details that are found in all minority ethnic books? Either they don't trust people writing in those languages, or just as bad, they barely gave them any thought when they issued their instructions. The first is plain discrimination; the second is the kind of subtle discrimination that non-whites in the US often complain of.

Minorities and foreign nationals, by contrast, have linguistic channels the Chinese government are not privy to

The Chinese government is privy to these linguistic channels because they have people of these ethnicities working for them and loyal to the Chinese government. Given the astronomical amounts China is spending on internal security, hiring a few more Tibetans, Uyghurs, Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, or Mongols to monitor what's going on in these languages should not be a big strain on the budget.

I find it interesting, by the way, that you group 'minorities and foreign nationals' together.

Bathrobe said,

July 26, 2018 @ 9:30 pm

Let me clarify a little. The staff member who refused to take the books kept opening them and saying "I can't read that". She refused to accept the publication details.

If she had said, "Our Mongolian-speaking staff member is not here today so I'm really sorry, I'm going to have to ask you to get certification for these books", I would have been annoyed but I would have understood. But it was clear from what she said that there was a blanket ban on sending books not written in Chinese characters (including Mongolian-language books published in China) unless accompanied by certification from the Cultural Bureau. That is a slight to recognised minorities. The idea that "Chinese books" are "books written in Chinese" is the kind of slight that, in my understanding, some non-mainstream Americans frequently get upset about. The exclusion from consideration on the basis of unspoken assumptions about what is "standard" or "normal".

Eidolon said,

July 26, 2018 @ 10:00 pm

@Bathrobe

It seemed you were implying that swamping the areas with Han Chinese was the Chinese government's solution to the problem of "allegiance." Doesn't that assume Han Chinese are "loyal"? Mind you, I disagree with this statement; I think it has much more to do with the Chinese government's perception of international law and its confidence in being able to control Han populations better.

> The Chinese government is privy to these linguistic channels because they have people of these ethnicities working for them and loyal to the Chinese government. Given the astronomical amounts China is spending on internal security, hiring a few more Tibetans, Uyghurs, Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, or Mongols to monitor what's going on in these languages should not be a big strain on the budget.

I think this is a gross underestimation of the cost of having reliable translators and monitors at every local government office, though I'm sure they are working on it, any way. We've talked about the limitations of bilingualism in China, in the past, so this shouldn't come as a surprise.

> I find it interesting, by the way, that you group 'minorities and foreign nationals' together.

Well, in this context, what I'm saying is that they all speak languages the vast majority of Chinese government officials do not understand, and so cannot as easily control or monitor. The fact that no exception is being made for foreign languages and nationals indicates that this is a censorship issue, above all – they're worried about the spread of "subversive" material in *any language* in China, but can only generally verify Chinese.

Bathrobe said,

July 26, 2018 @ 10:48 pm

swamping the areas with Han Chinese was the Chinese government's solution to the problem of "allegiance."

That is an interesting point. Personally, I think that the broad mass of Han can often be more unruly than ethnic minorities. And perhaps you are right that the difference is that they are more easily monitored and controlled in a practical sense.

I'm not sure that swamping areas with Han Chinese is a way of securing allegiance, although I'm sure it might have been a consideration for previous dynasties (including the Qing, who seemed almost Stalinist in their willingness to move people around). I do think the Han might be perceived as more "reliable" and familiar to deal with.

Han are probably also easier to use within established systems. For instance, rather than training Uyghurs as oil drilling or software engineers, it's no doubt easier to just ship Han in. Reliable, familiar, minimum of fuss.

This highlights a difference between "autonomy" and "independence". Foreign miners operating in Mongolia must employ a large numbers of Mongolians at all levels, even if the top levels are dominated by foreigners and English-speaking Mongolians. I don't think the same logic applies to Mongols in Inner Mongolia.

Philip Taylor said,

July 27, 2018 @ 2:36 am

Ellen K + Christian Weisgerber (OT discussion of Canadians' use of the term "American") — it may be that attitudes and/or language usage vary with province. I should have said that I was speaking only of Ontario citizens, the one group of Canadians with whom I have had significant contact (95% Ontario; 5% Québec; 0% all other provinces). And perhaps significant, specifically those in the Guelph and Waterloo/Kitchener communities, but not including Mennonites with whom I have never had such discussions.

Bathrobe said,

July 27, 2018 @ 7:36 pm

@Eidolon

Perhaps speaking of 'flooding' these areas with Han Chinese is not a precise way of putting it. It would be useful if we could actually do research into why Han Chinese moved/move to places like Tibet, Xinjiang, or Inner Mongolia. That research is obviously not going to happen (too sensitive), but sorting out when immigrants came and why would give a better picture of the situation.

The Chinese have traditionally used 屯田 / 军屯 methods to secure and develop unsettled or outlying areas. This involved sending military brigades and their families to form settlements, usually farming settlements. This was used in the early period after 1949 and was partly related to national security (defending the borders). Han settlers were also sent in to develop industrial production brigades.

But that is not enough to explain the current huge numbers of Han settlers in places like Xinjiang. I assume that many would have come to develop industry, for weapons development, etc. Many would have been posted with the government as administrators, teachers, policemen, soldiers, etc. And once Han settlement was well established, a momentum would have built up as shopkeepers, merchants, tourism operators, business opportunists, and many others would have been attracted by opportunities to service Han populations and visitors. I think it fair to say that this represents a process similar to colonisation.

In Inner Mongolia, it is possible to find areas where Han settlement dates back to the late Qing or Republican periods, motivated by land hunger and a desire to escape the chaotic conditions of the central provinces. There are areas like Wuhai, where the Mongol herding population was fairly sparse and Han were brought in to develop coal, power, metal-working and chemical industries. But the government has also been engaged in encouraging people to move to Inner Mongolia in large numbers, which is easily discovered if you speak to people there.

What is plain is that the Communist Party's belief that the Han must take the lead in bringing these people out of their backwardness and the concept that 'developing outlying regions' means bringing in the Han, has set in motion a dynamic leading to the marginalisation of the original people, resistance and pushback, and finally the government's current conviction that the job needs to be completed through thorough Sinification (or Hanification).

Adrian Morgan said,

July 28, 2018 @ 2:19 am

I once sent a copy of a children's book I authored to a friend in China (not Beijing), and do not know that she ever received it. This is the book. These things can happen for perfectly innocent reasons. But is it plausible that something political happened, and just for fun, can you think of a way to interpret the content as a Chinese political allegory?

Bathrobe said,

July 28, 2018 @ 3:35 am

Incidentally, in discussing Han settlement in Eastern Inner Mongolia, the role of the local Mongolian nobility renting or selling land to Han settlers during the Qing should also be mentioned. Despite government segregation between Han and Mongols, large amounts of land were rented or sold to Han agriculturalists because they could pay higher taxes than herders. Eventually many Mongols also moved from herding to cultivation. There are a lot of sources out there outlining historical developments in different areas.

With regard to Xinjiang, the Chinese government's Great Leap West, an ambitious undertaking to develop China's western frontier launched in 1999, has most obviously contributed to the recent influx of Han immigrants into the area.

James Wimberley said,

July 31, 2018 @ 7:35 am

Re the "Cultural Revolution" in quotes. For a long time the epicenter of typographical geopolitics was around Skopje. As a European civil servant I had to write the name of the country as "the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia", thus, with the quotes. The acronym FYROM was deprecated by the Macedonians, who feared it might stick. The Greeks insisted on the quotation marks round the suspect irredentist "Macedonia". I can't remember whether "former" was capitalised or not. The saga looks to be ending, as the Greek and Macedonian Prime Ministers have struck a deal: the name of the country will be the Republic of North Macedonia, without quotes.