Phonemic diversity decays "out of Africa"?

« previous post | next post »

A striking recent paper by Quentin Atkinson ("Phonemic Diversity Supports a Serial Founder Effect Model of Language Expansion from Africa", Science 4/15/2011) has been the subject of a lot of discussion recently. Its abstract:

Human genetic and phenotypic diversity declines with distance from Africa, as predicted by a serial founder effect in which successive population bottlenecks during range expansion progressively reduce diversity, underpinning support for an African origin of modern humans. Recent work suggests that a similar founder effect may operate on human culture and language. Here I show that the number of phonemes used in a global sample of 504 languages is also clinal and fits a serial founder–effect model of expansion from an inferred origin in Africa. This result, which is not explained by more recent demographic history, local language diversity, or statistical non-independence within language families, points to parallel mechanisms shaping genetic and linguistic diversity and supports an African origin of modern human languages.

This paper's premises are intriguing, if far from obvious, and its results are pretty compelling:

However, I have some concerns about what lies in between the assumptions and the results, especially concerning the way "Total Phoneme Diversity" is estimated. This measure gives (what seems to me to be) excessive weight to certain features, ignores syllable structure, and (as a result) is heavily influenced by a few areal characteristics that are as likely to be innovations as survivals.

Let's start by looking at what Prof. Atkinson did. From the Supporting Online Material:

Data on phoneme inventory size were taken from the World Atlas of Language Structures (WALS – available online at http://www.wals.info/) (S1-S4) together with information on each language’s taxonomic affiliation (family, subfamily and genus) and geographic location (longitude and latitude). WALS contains information on three elements of phonemic diversity – vowel (S2), consonant (S3) and tone (S4) diversity – in a total of 567 languages. Due to uncertainty in ascertaining exact inventory counts across languages, the WALS data are binned into ranges for vowel (small [2-4], medium [5-6], large [7-14]), consonant (small [6-14], moderately small [15-18], average [19-25], moderately large [26-33], large [34+]) and tone (no tone, simple tone and complex tone) diversity. Uncertainty associated with these diversity assignments is only expected to weaken any clinal relationship with geography. WALS values for the three items were standardized (subtracting the mean value and then dividing the difference by the standard deviation) so that they were on comparable scales (mean = 0, standard deviation = 1). The standardized scores were then averaged to produce a measure of total phonemic diversity in each language.

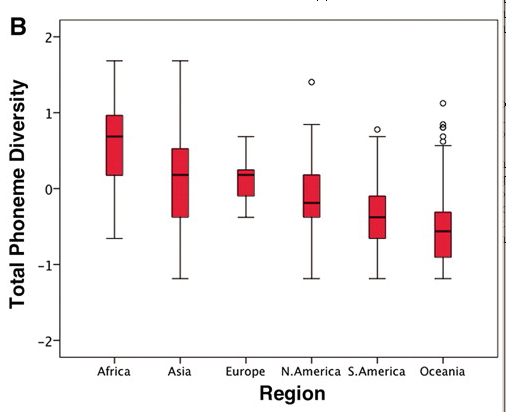

Here is a boxplot giving the distributions of scores by region:

Given the continent-level distributions, it's not surprising that a plot of individual languages by distance from a putative origin in Africa falls off in a convincing way:

As the plot's caption explains,

Distance from the origin alone explains 30% of the variation in phonemic diversity (fitted line; r = –0.545, n = 504 languages, P < 0.001) and 19.2% of the variation after controlling for modern speaker population size.

The text tells us that

The relationship also holds for vowel (r = –0.394, P < 0.001), consonant (r = –0.260, P < 0.001), and tone diversity (r = –0.391, P < 0.001) separately.

But there's something about Atkinson's "Total Phoneme Diversity" that should strike you as odd. Tone, vowel, and consonant "diversity" are weighted equally, although the numbers of alternatives and the contribution to syllable- or word-level "diversity" are radically different in the three cases. Thus losing a single tone would generally reduce "Total Phoneme Diversity" by as much as losing about 10 consonants would. Worse, the lost tonal feature would probably give us only one pair of phonological "alleles" per syllable, at most, while the consonant choices would probably be available (to different extents in different languages) in several places in a syllable, so that the equivalent reduction in "phonemic variants" — seen as alternative symbols in different functional locations — might be numbered in the hundreds.

So let's take a closer look at how "Total Phoneme Diversity" was calculated. The data comes from M. Haspelmath, M. S. Dryer, D. Gil, B. Comrie, Eds., The World Atlas of Language Structures Online (Max Planck Digital Library, Munich, 2008), where (for plausible typological reasons) the phonological inventories of up to 567 languages are treated in a coarsely granular way.

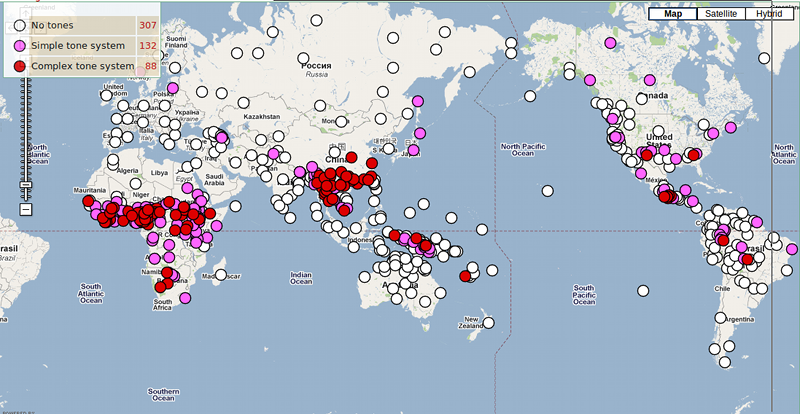

The WALS tone inventories are divided into three classes, "no tones", "simple tone systems", "complex tone systems". After Atkinson's "normalization" (subtraction of the mean and division by the standard deviation) the three possible values for tone-inventory size turn into the numerical values -0.769, 0.547, and 1.862. Given that the "Total Normalized Phoneme Diversity" is the average of tone, vowel, and consonant measures, the contribution of the three possible values of "Normalized Tone Diversity" to the total will be -0.256, 0.182, 0.621.

| No tones | (307 languages) | diversity = -0.769 |

| Simple tone system | (132 languages) | diversity = 0.547 |

| Complex tone system | (88 languages) | diversity = 1.862 |

Here's corresponding map:

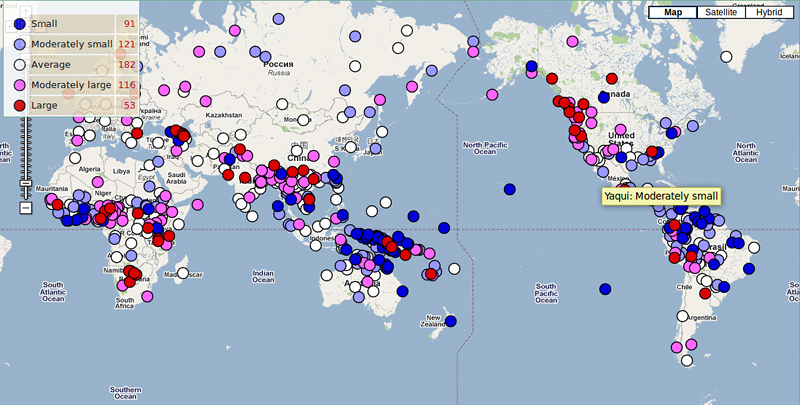

Here are the consonant inventories:

| Small | 6-14 | (91 languages) | diversity = -1.554 |

| Moderately small | 15-18 | (121 languages) | diversity = -0.717 |

| Average | 19-25 | (182 languages) | diversity = 0.120 |

| Moderately large | 26-33 | (116 languages) | diversity = 0.958 |

| Large | 33+ | (53 languages) | diversity = 1.795 |

And the corresponding consonant map:

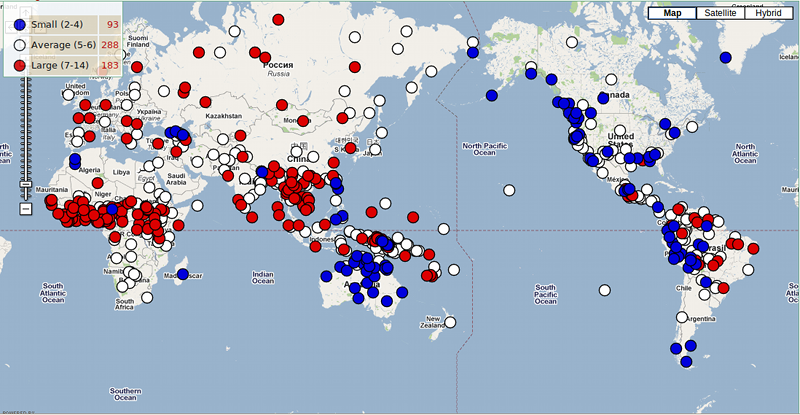

The WALS vowel inventories:

| Small (2-4) | (93 languages) | diversity = -1.235 |

| Average (5-6) | (288 languages) | diversity = -0.485 |

| Large (7-14) | (183 languages) | diversity = 1.390 |

And the corresponding vowel map:

It was plausible for the people who put the WALS data together to bin the phonological inventories so coarsely. (Ian Maddieson wrote the relevant chapters, but I suppose that the decision about how to quantize inventories was a joint one.) For a start, this coarse quantization avoids a lot of detailed argumentation about exactly how to analyze specific languages, like our recent discussion over whether /hw/ is a doubly-articulated consonant (and thus an addition of one to the consonant count) or a sequence of two consonants (and thus omitted from the count). I'm not sure that I would have made the same choice, but anyhow, it's done, and the facts on the WALS ground thus limited Atkinson's options.

However, this combination of coarse binning into ranges, for functionally-defined subsets of elements with radically different numbers of members, seems to me to be much more problematic for Atkinson's purposes. It's as if a human genomic survey made geographically localized counts of the number of alleles involved in color vision and in blood physiology, divided each set of counts into a few bins ("a little variation", "a medium amount of variation", "a lot of variation"), standardized the binned counts for each functional class separately, and averaged the results, thus giving as much weight to each color-vision variant as to several orders of magnitude more blood-physiology variants. This might be OK, but choosing to give this kind of boost to features that happen to be enriched in one region or another will obviously push the results around by a considerable amount.

And indeed in this case, a few areal features (which might well be innovations rather than retained characteristics) have an outsized effect on the results. For example, nearly all the languages of sub-Saharan Africa have lexical tone. To quantify the effect of that single feature, I downloaded the WALS data and crudely segregated the data for Africa, Europe, and South America (using latitude and longitude rectangles, since continent is not noted in the database). On that basis, the average "Normalized Tone Diversity" of those three regions was 0.934 for Africa, -0.450 for South America, and -0.637 for Europe — a difference of more than one and a half standard deviations, reflecting an areal distribution of what is basically a single phonological feature.

Dividing by three and subtracting, this would shift Africa by -0.524 in "Total Phonemic Diversity" relative to Europe, and by -0.461 relative to South America, which is roughly what the overall mean regional differences are.

There are some similar effects for vowels — many African languages use vowel nasality and/or the "advanced tongue root" feature to double or quadruple their vowel inventories, while keeping their syllable structure simple. Such things happen to vowels elsewhere in the world, but (in most places) not as often; roughly in compensation, languages elsewhere tend on average to have more complex syllable structures.

Overall, as I noted above, it's not at all obvious what we ought to count in creating data for such a project. Should we generally count long and short vowels as separate entities or as sequences? What about monophthongs and diphthongs? Or nasal and oral vowels? If we delete syllable-final nasals (retaining syllable-initial nasals) and instead encode the same information in nasality of an inventory of 4 vowels, it looks like we've doubled the number of vowels — moving us from a small (2-4) number of vowels to a large (7-14) number of vowels — while leaving the consonant inventory unchanged.

These questions (and many others having to do with syllable and morpheme structure) don't just add noise to the data. Many such features are "areal" — spread over geographical areas of related (and even unrelated) languages, and also spread over local descriptive practices among linguists. The areas in question often approach continental size, and thus these phenomena (and our choices about how to code them) can have a big influence on the outcome of algorithms that look for world-wide clines in the "diversity" measures that result from these choices.

Finally, it's worth adding a few words on a key assumption of this work, laid out with admirable clarity in the opening sentences:

The number of phonemes—perceptually distinct units of sound that differentiate words—in a language is positively correlated with the size of its speaker population (1) in such a way that small populations have fewer phonemes. Languages continually gain and lose phonemes because of stochastic processes (2, 3). If phoneme distinctions are more likely to be lost in small founder populations, then a succession of founder events during range expansion should progressively reduce phonemic diversity with increasing distance from the point of origin, paralleling the serial founder effect observed in population genetics (4–9).

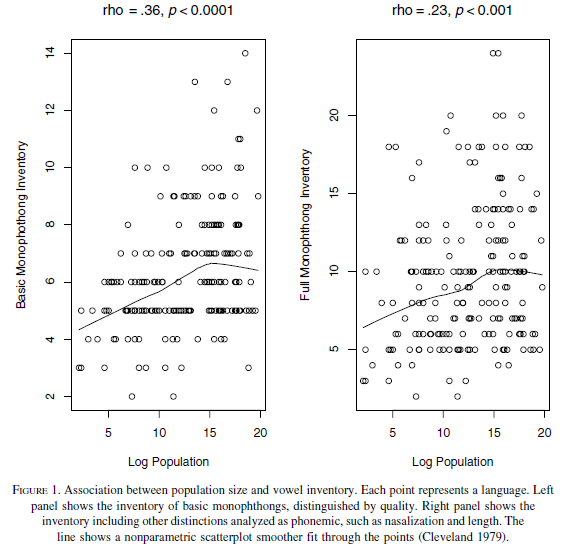

Reference (1) is Jennifer Hay and Laurie Bauer, "Phoneme inventory size and population size", Language 2007. The data reviewed in that paper is certainly consistent with the hypothesized "founder effect", as exemplified by their Figure 1:

I was initially somewhat skeptical of this result, but the effects seem to be quite robust over data sets, modes of analysis, correction for various possible confounding factors, etc. The most plausible remaining possible artefact seems to be the issue that Hay and Bauer describe this way:

A reviewer of this paper suggested that it could be possible that the number of ‘phonemes’ in a language tends to increase as the language is studied, and that languages spoken by more speakers tend to receive more attention. This is an intriguing suggestion, which would provide a sociological explanation for our observed effect. However this portion of our analysis has reduced each language family to one data point – investigating the mean population size and phoneme inventory by language family. This eliminates the possibility that a few highly studied language families (such as Indo-European) might be driving the effect in this way. The fact that the correlation is robust both across languages and language families suggests strongly that there is something here that requires explanation.

As is often the case, this territory has previously been explored by the eminent American linguist, Dave Barry (Dentists in Paradise), including a discussion of the concomitant increase in average morpheme length:

The Hawaiian language is quite unusual because when the original Polynesians came in their canoes, most of their consonants were washed overboard in a storm, and they arrived here with almost nothing but vowels. All the streets have names like Kal'ia'iou'amaa'aaa'eiou, and many street signs spontaneously generate new syllables during the night.

Let me close with a plug for the forthcoming report, "Fashion Diversity Supports a Serial Founder Effect Model of Expansion From North-Central France", extending my own seminal work in "The Hunt for the Hat Gene". I can't reveal too much, since the work is still under embargo, but it has been conclusively established that smaller populations have fewer styles of dress (including fewer kinds of hats), so that we should expect the global distribution of diversity in clothing and headgear to show the effect of population bottlenecks in the migration of humans from our ancestral home in the valley of the Seine.

Sili said,

April 16, 2011 @ 4:06 pm

But hats support Panspermia!

D said,

April 16, 2011 @ 4:18 pm

I am getting more and more skeptical about the use of the WALS for these types of comparative studies. It seems to filled with either inaccuracies, or one language not being treated the same way as another one.

Since it seems to gather its information from different academic texts by unaffiliated authors, it's not very surprising. Different authors have different ideas of what exactly consists say a tonal language or a grammatical gender. If someone of persuasion A is the source for language X, and someone of persuasion B for language Y, any comparison will be inaccurate.

Richard Sproat said,

April 16, 2011 @ 4:35 pm

It's not always easy to determine the scope of Mark's irony, so perhaps he intended to cast doubt on the population/phoneme-inventory-size correlation too.

In any event, one point that I would like to add is that we have yet to see any demonstration that the Hay/Bauer correlation is valid for population ranges plausible for the Paleolithic. Paleolithic languages would all have been spoken by small populations. Is there any serious reason to believe that a migrant population of a few tens of individuals would have shown less diversity than the "mother" population of a few hundreds of individuals?

Because that's what you gotta believe if you accept Atkinson's thesis.

[(myl) I'm not sure that this is true. For example, Dixon (in The Rise and Fall of Languages) argues that under the conditions of contact existing in pre-colonial Australia, borrowing (even across language families) due to contact phenomena was so prevalent that feature after feature spread in an areal fashion, to the point where a tree-structured model of development doesn't apply any more. On his account, tree-like linguistic history only happens when you have rapid expansion of a human population over a previously-unpopulated area, as in the IE expansion over the Asian steppes.

There's certainly room for discussion of how true that is, but Dixon is neither stupid nor ignorant, to say the least, and his ideas are (as far as I can see) exactly the linguistic equivalent of the "serial founder effect".]

YM said,

April 16, 2011 @ 4:44 pm

Personally, I don't see much of any correlation in Hay and Bauer's scatterplots. They really don't offer much support for a model of phoneme inventory size.

NB "log population" in their diagrams seems to be the natural logarithm, not base 10.

[(myl) You don't see much correlation because there isn't much — r=0.23 means that only 5% of the variance is accounted for; r=0.36 means that 13% is. But a low correlation is not no correlation, and it's often true in evolutionary dynamics that a small effect, iterated over many generations, is amplified rather than reduced.

Whether that's going to work in the case under discussion depends on the balance between the rate of phonetic innovation (over the historical period since hypothetical out-of-Africa migrations) and whatever the phonological consequences of a small population-size effect might have been under whatever conditions applied during those historical migrations. This is the part that worries me most here — 10,000 or 100,000 years seems to be plenty of time for enough phonemic splits and mergers to have occurred to obscure any "serial founder's effect".]

Razib Khan said,

April 16, 2011 @ 4:45 pm

bravo! incredibly illuminating post for us civilians.

YM said,

April 16, 2011 @ 4:59 pm

…and another exercise in subjective correlation: look at the diagram of phoneme diversity vs. distance from Africa. Cover with your hand first the area to the left of ca. 14,000 km, then the area to the left. What you have are two uncorrelated lumps, with the far lump slightly lower than the left one. These correspond roughly to the old world and the Americas.

In other words, all this graph says is that phoneme diversity in the Americas, taken as a whole, is somewhat less than Eurasia+Africa, taken as a whole. No more. And of course it doesn't account for the great diversity of phoneme inventory size within the Americas.

African ur-language reconsidered | Gene Expression | Discover Magazine said,

April 16, 2011 @ 5:30 pm

[…] Mark Liberman at Language Log has looked through the Science paper Phonemic Diversity Supports a Serial Founder Effect Model of Language Expansion from Africa. Overall he seems to think it is an interesting paper, but he has some pointed criticisms. Here's the utility of the post: Liberman uses analogies to domains (e.g., genomics) which are comprehensible to me. My main issue with linguistic evolution is that I'm so ignorant that I barely understand the features being discussed. I may know their dictionary.com definition, but I have pretty much no deep comprehension with which to test the inferences against. By analogy, imagine trying to evaluate a morphological cladistic model with no understanding of anatomy. Here's the part which may be of particular interest to readers of this weblog: However, this combination of coarse binning into ranges, for functionally-defined subsets of elements with radically different numbers of members, seems to me to be much more problematic for Atkinson's purposes. It's as if a human genomic survey made geographically localized counts of the number of alleles involved in color vision and in blood physiology, divided each set of counts into a few bins ("a little variation", "a medium amount of variation", "a lot of variation"), standardized the binned counts for each functional class separately, and averaged the results, thus giving as much weight to each color-vision variant as to several orders of magnitude more blood-physiology variants. This might be OK, but choosing to give this kind of boost to features that happen to be enriched in one region or another will obviously push the results around by a considerable amount […]

J.W. Brewer said,

April 16, 2011 @ 5:48 pm

I see the point about the limitations of WALS (either because of lack of consistency in the underlying sources of info for different languages or the lack of granularity), but that I suppose raises the broader question of whether we really have the sort of data that will make *any* sweeping claims of a comparative/typological nature sufficiently data-driven. If not, how would we get it? There's also the question for this sort of thing as to how one measures distance from Africa. The assumption seems to be that the process of migration that brought Polynesian-speakers to Hawaii is relevant but the process of migration that brought IE-speakers to Hawaii is irrelevant. But the lag between the two arrivals seems to be estimated at somewhere between 600 and 1500 years, which all seems rounding error in a theory about the last 75,000 years.

Tyrone Slothrop said,

April 16, 2011 @ 5:58 pm

The issue concerning vowels is important. Consider, Navajo, for example, where, when adding in tone (high tone and default low tone), vowel length, vowel length pluse tone (high tone, rising tone, falling tone, and default low tone), and oral versus nasal vowels (which can also be long or short, high or low, rising or falling), the phonemic inventory for vowels becomes 48. Or you could claim that Navajo has four vowels (i,e,a,o). That seems a rather large difference.

German Dziebel said,

April 16, 2011 @ 6:02 pm

@Richard Sproat

"Is there any serious reason to believe that a migrant population of a few tens of individuals would have shown less diversity than the "mother" population of a few hundreds of individuals?'

I agree. At the dawn of out of Africa idea, geneticist James Neel, famous for his work on tribal genetics,published a paper entitled Estrutura populacional de amerindios e algumas interpretacoes sobre evolucao humana. In it, he criticized out of Africa for exactly the same reasons. Pleistocene populations were small and subdivided and all founder effects negligible. The out of Africa theory takes an expanded intermixed African population (think of Tokyo or New York) and then derives smaller, more isolated non-African populations from it. Then comes Atkinson, falls into the trap and finds the same pattern in phoneme inventories. Truth be told, I was intrigued by his Fig S6, Suppl Mat, in which the best-fit second origin region is South America (Suppl. Mat Fig. S6). This is precisely the area of world highest language diversity measured in terms of independent stocks. Amazonia is the area with the greatest number of language isolates, which are also small populations.And small populations apparently tend to maintain smaller phonemic inventories.

John said,

April 16, 2011 @ 6:29 pm

I like YM's comments.

I'd also be curious about the way in which distance was measured and defined. Given a range over which a language was/is spoken, how is the distance measured? Also distance is different from travel time, as anyone who has tried to cross the Mediterranean on foot can tell you.

J.W. Brewer said,

April 16, 2011 @ 6:39 pm

Another things just from eyeballing the maps myl did: the indigenous languges of Australia seem less "complex" in all 3 dimensions (or, more precisely, to have less variation away from simplicity) than the indigenous languages of the Americas, but on most accounts the immigrant ancestors of the aboriginal Australians got there tens of thousands of years before anyone crossed the Bering land bridge, so the Australian languages are closer to Africa both in mileage and in time.

I think the standard account is that tone is an innovation in Sinitic languages within historic times. Is there any consensus on how ancient versus recent the prevalence of tone in sub-Saharan African languages is?

Dw said,

April 16, 2011 @ 7:15 pm

Perhaps one could count the number of distinctive syllables, rather than phonemes, to get a somewhat less subjective measure of phonological complexity. Using this measure, for example, a variety of English with the wine-whine merger is unambiguously less complex than one without the merger.

Ryan Denzer-King said,

April 16, 2011 @ 8:55 pm

I think the question of "diversity" is an interesting one and requires a significant amount of thought. For instance, do all languages with the same number of phonemes have equal phonemic diversity? It seems to me that a hypothetical language L with 7 consonants at 7 places of articulation would have more "diversity" in some sense than a language M with 7 consonants at 3 places of articulation. Perhaps discussion of phonemic diversity would be well-served by reference to phonological features?

[(myl) There's diversity in features (though this depends more than a little on what features you use), there's diversity in what segmental combinations of features occur, there's diversity in what sequences of segmental combinations of features occur, …

You could treat syllable- or foot-sized units as setting up the framework in which features can vary, and treat each feature-in-a-syllabic-position as the analogue to an "allele". This is what would be most closely analogous to the notions of genetic diversity, as far as I understand the situation (which is not very deeply).

It's also not completely obvious that inventories per "language" are what should be counted. Maybe an area with a large number of different languages should count has having greater "phonological diversity" than a comparably-sized region with only one language, even if the single language has a much larger phonological inventory (by whatever language-internal count) than the multiple languages do.

The consequences of different choices are going to be quite different assignments of "diversity" to geography, I think.

But anyhow, it seems to me that Prof. Atkinson deserves a lot of credit for taking what WALS made available, and looking into what it seems to suggest.]

Dw said,

April 16, 2011 @ 9:50 pm

@Ryan Denzer-King:

a hypothetical language L with 7 consonants at 7 places of articulation would have more "diversity" in some sense than a language M with 7 consonants at 3 places of articulation

In this scenario your language M would presumably be making some orthogonal contrasts — e.g. of voicing or phonation — that language L is not making.

Jerry Friedman said,

April 16, 2011 @ 10:03 pm

@Dw: Yes, precisely as a variety with the spas-spars merger is less complex than one without it.

Steve Kass said,

April 16, 2011 @ 10:39 pm

I can add a less-subjective assessment of YM’s earlier observation, and then some.

In the scatterplot, it looked to me like there could be a “sawtooth” relationship. Is it possible that within each individual continent, an upward-sloping line segment fits better then the overall fit the authors find? (In other words, is the so-called ecological fallacy of statistics at play in the analysis?)

The authors didn’t provide the variable “Continent” in their supplemental tables, so I didn’t compute exact continent-by-continent correlation coefficients. But just about half the languages in the data set are located at least 13,500 km “from Africa,” and these languages comprise roughly Oceania, North America, and South America. (More detail below on exactly what the distance number means.)

Within this subset of languages, there was no explanatory linear relationship (r=0.03) between the distance from Africa and that other variable the authors studied, which I’ll call NUBEWVCTDfWS. (NUBEWVCTDfWS, for normalized, non-uniformly binned, and equally weighted vowel, consonant, and tone data from a web site. They call it phonemic diversity. Mark sharply questioned its value in representing that concept.)

A linguist (I am not one) might be able to code each language group’s continent fairly quickly. Perhaps there are correlations for some individual continents, perhaps not, but they are almost surely weaker within continents, and weaker to a greater degree than expected only from the “restriction of range” phenomenon.

If this is the case, why would the authors’ hypothesis hold between continents, but not within them, especially if migration into each continent has a well-defined point of origin?

[There was a correlation for the languages less than 13,500 miles from Africa, but I didn’t look closely, and at a glance, I think the trend stops or reverses when it gets beyond the Indian subcontinent and into East Asia.]

[More about distance from Africa, as promised:

According to the supplemental materials, distance from Africa, one of the key variables in the analysis, is defined by the length of a piecewise great-circular path from the origin location. Piecewise, in that the path is required to pass between continents via specific waypoints (at about what are now Suez, Istanbul, the Bering Strait, Ho Chi Minh City, and Panama).

This was done so that distances “more accurately reflected plausible migration scenarios.” Notwithstanding the relative novelty of intracontinental air travel, this makes some sense as at least an approximation.]

Kai said,

April 16, 2011 @ 10:42 pm

One major problem with this hypothesis concerns the fact that people can learn new languages; learning new genes or phenotypes is considerably harder.

Any study which combines Spanish speaking Mexicans and South Americans of Native American descent with Spanish speaking Europeans and professes to say something about human genetic diversity is flawed. Indo-european was a language once, spoken by a specific group of people. Who are their direct descendants? Iranians? The English? Ukranians?

A geneticist said,

April 16, 2011 @ 10:54 pm

As a geneticist i am agnostic about the basic claim of a single origin for language, but this argument based on an analogy with genetic diversity strikes me as ludicrous. True, genotypes are more varied in Africa; but there's more to it than that. In general, the genes found outside of africa are a subset of those found within africa, indicating that african genes passed through a bottleneck. With language, the argument is only superficially similar; in fact, the argument is analogous to the claim that individual humans living further from Africa have fewer than the 20K genes of Africans. (in fact, all humans have the same number of genes. What varies is the diversity of variants of each gene within a population. ). Unless I am really misunderstanding something, the basic argument is nonsensical.

Dw said,

April 16, 2011 @ 10:56 pm

It just occurred to me that this hypothesis explains why cot-caught merged speakers tend (on average) to live in the west of the US.

It's not because of historical migration patterns: it's because the Western US is further away from Africa than the East :)

Steve Kass said,

April 16, 2011 @ 11:28 pm

Dw: Except that the Western US is closer to Africa for this theory; the only road from Africa to North America passes through the Bering Strait. (And “English” is closer to Africa than either coast of the U.S., being at 52ºN 0ºW in the data set.

(It’s Mary=merry=marry and caught=cot, for me, in any case.)

Jens Fiederer said,

April 16, 2011 @ 11:57 pm

Dave Barry's flotsam theory of Hawaiian seems reasonable, but my theory that the Hawaiians were once united with the Czechs, divorced, and in the settlement one got the vowels and the other the consonants explains far more.

D.O. said,

April 17, 2011 @ 12:29 am

Maybe I am beating the same drum as German Dziebel and A geneticist, but still. Looking at Hay and Bauer chart and assuming that horizontal axis is natural log, we see that increase in morphological inventory continues to approximately ln(pop)=15 that is pop = 3 mil. This is surely a very large population for single language, achieved only after the initial migration from Africa. This suggests that if morphological inventory dependence on population is not spurious, it is maintained by expansion/contraction of the inventory on relatively short historical times. And thus has no relation to the founding effect.

maidhc said,

April 17, 2011 @ 3:34 am

If the number of phonemes in a language is a function of group size, why would prehistoric people in Africa have more phonemes than migrants out of Africa? As far as I know, there isn't any evidence that prehistoric Africans lived any differently than non-Africans. Until a few thousand years ago, everyone lived in small groups of hunter-gatherers. Was it proximity to the fabled phoneme mines of the Rift Valley?

[(myl) From the wikipedia article on the "Founder Effect":

(I've edited the passage lightly to correct some apparently non-native ungrammatical English). The general idea is that the effect size of the gene pool in an isolated migrating population is smaller than in the homeland. In some cases, the migrating group may become very small due to the rigors of the journey, but this assumption is not necessary. As I understand it, the key point is that the gene flow between the migrating group and the homeland is substantially reduced or cut off entirely.

Obviously in the case of linguistic rather than genetic diversity, we're talking about a "meme pooll" rather than a "gene pool". But the same arguments might in principle apply.]

I don't know about phonemes, but areas where people still live in small groups, like Australian aborigines and the natives of New Guinea, are generally cited as examples of linguistic diversity. Are Australian aboriginal languages phonemically similar despite their many other differences?

That's a particularly interesting case because genetically it appears that the number of original migrants into Australia may have been quite small, perhaps even just a single group. There's not any good evidence about the state of ocean navigation 50,000 years ago. The aborigines did manage to get to Tasmania. Unfortunately there are not any Tasmanian aborigines left, so it's not possible to do a genetic study to determine when this happened. I presume there's not much in the way of records about their languages either.

It's a bit shocking and not much of a credit to our "civilization" that a people could live somewhere for thousands of years, preserving all sorts of valuable information, and then suddenly disappear, thanks to us, before we knew enough to make use of it.

(A couple of ABC shows I have heard have said that there are still a few people around who claim Tasmanian aborigine ancestry, descendants of aboriginal women who were taken by white men to some remote places.)

army1987 said,

April 17, 2011 @ 4:58 am

In the scatterplot, it looked to me like there could be a “sawtooth” relationship. Is it possible that within each individual continent, an upward-sloping line segment fits better then the overall fit the authors find? (In other words, is the so-called ecological fallacy of statistics at play in the analysis?)

Well, the authors were trying to find out whether bottlenecks would decrease the number of phonemes, and bottlenecks presumably would mainly occur between one continent and the next rather than within a continent. (Not that I find this whole thing that convincing.)

GeorgeW said,

April 17, 2011 @ 5:25 am

This is an outstanding post and the comments are interesting and enlightening. These express some reasonable scepticism.

I would be interested in reading alternate explanations for Atkinson's findings. Is the 30% correlation just a statistical fluke, a mistake, or is there some other factor at work?

[(myl) Take a look at Anscombe's quartet to see how a bunch of different data patterns can lead to (in that case) a correlation of r=0.816.

In the present case, we start with some nearly-continent-sized areal features, clearly visible in the WALS plots. Geographical non-homogeneity of that kind is likely to lead to correlations with geographically-defined variables. So the question is not why such geographical correlations exist — the most obvious general answer is a combination of "locality of related languages" and "contact phenomena" — but why they have the particular properties that they do.

Atkinson's hypothesis is that there's a "serial founder's effect" on phonological inventories, superimposed on areal effects from other causes, and we can see it in the WALS data. The null hypothesis, I think, would be that the geographical correlations are caused by areal effects which are random relative to migratory distances; and that the particular data applied in this test is biased by the choice of some features and methods of quantification that happen to make Africa look like an area of high diversity.]

Richard Sproat said,

April 17, 2011 @ 6:31 am

[(myl) I'm not sure that this is true. For example, Dixon (in The Rise and Fall of Languages) argues that under the conditions of contact existing in pre-colonial Australia, borrowing (even across language families) due to contact phenomena was so prevalent that feature after feature spread in an areal fashion, to the point where a tree-structured model of development doesn't apply any more. On his account, tree-like linguistic history only happens when you have rapid expansion of a human population over a previously-unpopulated area, as in the IE expansion over the Asian steppes.

There's certainly room for discussion of how true that is, but Dixon is neither stupid nor ignorant, to say the least, and his ideas are (as far as I can see) exactly the linguistic equivalent of the "serial founder effect".]

Maybe it's too early in the morning but this seems orthogonal to me. My point was simply that if Atkinson is to be taken seriously, one has to believe that a small population gives rise to an even smaller migrant population and this is the source of the purported reduction in phoneme diversity as one proceeds away from Africa, because the even smaller population is prone to loss of phoneme diversity.

Dixon could well be right on these points but this doesn't seem to bear on the point here which is the sequence of events one must believe in if one is to believe Atkinson's theory. If nothing else, Dixon's suggestion seems to be more informed by what we do know about language contact.

[(myl) For there to be a "serial founder effect" in "phonological diversity", it would have to be true that in the homeland, there's enough contact (with other dialects, related languages, or entirely different languages) for phonetic innovation to spread via diffusion (just as gene flow spreads mutations in the homeland's gene pool), while in a situation of migration into relatively empty territory, this process of diffusion (of both genes and memes) stops.

Otherwise you're right, it's hard to see why a band of 10 people should undergo a process of phonetic impoverishment that wouldn't afflict a band of 100.]

GeorgeW said,

April 17, 2011 @ 7:47 am

@Richard Sproat: Are you saying that there can be a loss in phonemic diversity due to founder effect on a smaller geographical and time scale, but not the scale claimed by Atkinson?

Claire Bowern said,

April 17, 2011 @ 7:59 am

This comment is particularly in relation to Mark's annotation to Richard Sproat's comment. The role of diffusion in language change has been vastly overstated in Australia. Yes, there is contact, but the cases that have been taken as typical (Heath's (1978) study of Eastern Arnhem Land and McConvell's work on Gurindji) are not typical. Moreover, there are pretty good methodological and theoretical (as well as empirical) reasons to doubt Dixon's conclusions. I set some of them out in a 2006 paper (available here). For example, rapid expansion is not correlated with more branching tree-like structure. Regarding tree structure in Australian languages, see my 2011 LSA paper, which I think showed fairly convincingly that phylogenetic reconstruction is possible for Australia.

The original comment is here.

[(myl) Thanks, Claire! Your 2006 paper certainly makes a strong case that Dixon goes too far — it was one of the things that I had in mind when I wrote that there's plenty of room for debate about those ideas. In this case, though, what's relevant is the relationship of these ideas to the hypothesis that there might be a "serial founder effect" somehow visible in "linguistic diversity", however quantified. And my point was just that even in a situation of low population density of small hunter-gatherer bands, there can apparently be diffusion of linguistic features across a wide geographical area. Dixon may well have overstated the role of contact, but as you observe, diffusion does exist at some rate in such situations.

It's less clear that the circumstances of "out of Africa" spread would generally have reduced or eliminated such diffusion. But apparently this happened for genes, and so it's not beyond the bounds of plausibility that it should have happened for memes.]

David Nash said,

April 17, 2011 @ 8:45 am

@maidhc (and @ J.W. Brewer)

In short, yes; as was outlined in a paper almost 50 years ago, which also can be seen as prefiguring a part of Atkinson's:

'Obtaining an index of phonological differentiation from the construction of non-existent minimax systems', by Voegelin, Wurm, O'Grady, Matsuda, and Voegelin, IJAL 29.1(1963),4-28

The authors proposed an index of phonological differentiation (of phonemic inventories), and calculated it for six language areas, the last and in a way least of which is Australia.

Doug said,

April 17, 2011 @ 9:37 am

MYL wrote: "[(myl) For there to be a "serial founder effect" in "phonological diversity", it would have to be true that in the homeland, there's enough contact (with other dialects, related languages, or entirely different languages) for phonetic innovation to spread via diffusion (just as gene flow spreads mutations in the homeland's gene pool), while in a situation of migration into relatively empty territory, this process of diffusion (of both genes and memes) stops. . . .]"

I'm not sure I understand this, at least if "phonological diversity" is being measured by the phoneme count, as in the original article.

In biology, there would be a founder effect even if, after the migration of the "founder" group, there was no diffusion or mutation at all affecting either the homeland or the new split-off founder group. The small founder group would almost certainly possess fewer gene variants than the larger home population. They left behind a large portion of the original population's genes.

But with languages, if the language was essentially uniform to start with, then the split-off founder group, no matter how small, brought with it all the vowels and consonants of the original group's language. So if there is indeed a correlation between language size (number of speakers) and the size of the language's phoneme inventory, the explanation must be different.

Also, greater diffusion in the homeland would not explain a larger phoneme inventory, as far as I can see. Mergers eliminating distinctions can spread just as well as new phonemes can, so I don't see why a language more exposed to diffusion would on balance be expected to have a larger phoneme inventory.

German Dziebel said,

April 17, 2011 @ 12:24 pm

@A geneticist

"In general, the genes found outside of africa are a subset of those found within africa, indicating that african genes passed through a bottleneck."

But from 1492 on, genes found outside of the Americas have grown to become a subset of those found within the Americas, the latter having absorbed populations from every region of the world. Not only that the out of Africa argument is ludicrous for phonemes, it's ludicrous for genes as well.

Steve Kass said,

April 17, 2011 @ 12:30 pm

Doug said,

In the paper’s supplementary materials (which are not behind a paywall), the authors mention (and give some references) that the split-off group might bring with it only “part of the dialect variation from the parent population.” So while bringing with them no fewer consonants and vowels (because they bring the whole language) they might bring with them fewer distinct sounds — a smaller repertoire of sounds that could over time come to distinguish meanings.

Ives Goddard said,

April 17, 2011 @ 1:52 pm

Only the WALS consonant number could possibly be significant here, since the way vowels (qualities only) and tones are binned they tell us almost nothing about the size and variety of attested syllable nuclei. But look at the WALS map for the 53 “large” consonant inventories (with 34 and up): Asia 16 (Caucasus 7, others 9), Africa 13 (click languages 7, others 6), North America 12 (Northwest and northern California 9, others 3), Europe, South America, and Oceania 4 each. So, large consonant inventories (on these data) are not more apt to be found in Africa, but they do have a distribution that is non-random and unexplained. And of course the numbers could be increased if WALS had correctly classified Abkhaz (say 58) and Slavey (37) and had included, for example, Ubykh (80), Tanaina (36), and conservative Peel River Eastern Gwich’in (53).

Teo said,

April 17, 2011 @ 4:36 pm

I'm assuming Atkinson only used phonemic diversity because there were prior studies claiming that the number of phonemes is correlated with founder effects.

[(myl) There are no such studies, as far as I know.]

>, it's not at all clear why this particular set of data should be used, apart from the fact that it, and not other sets of data, is somehow consistent with OoA. What if they had used S, O & V orderings? Surely, the number of orderings and patterns found outside South America is a subset of those found there. So?

[(myl) No doubt the WALS dataset was used because it's well-regarded and it's available. The idea of using word-order diversity — at least at the SVO level — is a non-starter, I think, since there are so few possible alternatives, and such a short half-life for particular options in the attested history of languages.]

Also, why not take a look at the number of language families? Even if we take into account the fact the the current family count for Africa may be underestimated (there are many unclassified languages and problematic groups like Nilo-Saharan and even Khoisan), Africa seems to have relatively few family-level linguistic groups considering its size, certainly very few if we compare the numbers to those of New Guinea or the Americas. Of course, entire language families may have been wiped out, but the same may be true of phonemic patterns there and elsewhere due to the effects of contact and cultural subjugation.

[(myl) I'm not at all sure that Africa does have fewer family-level linguistic groups than other areas. It happens that Joseph Greenberg, a well-known lumper, has persuaded most people to accept his (strongly lumped) classification of African languages. But several of the family groups, such as West Atlantic, have little or nothing to hold them together except for geographical proximity and a few shared features that might well have been borrowed.]

Richard Sproat said,

April 17, 2011 @ 4:46 pm

[GeorgeW

@Richard Sproat: Are you saying that there can be a loss in phonemic diversity due to founder effect on a smaller geographical and time scale, but not the scale claimed by Atkinson?]

No that's not what I'm saying. My point is simply that Paleolithic populations were all tiny, and Atkinson has no evidence whatever that there is any correlation of population size and phoneme diversity in population size ranges plausible for the Paleolithic. That was the substance of my main argument in my review for Science.

When you add in Mark's excellent observations about the biases in how the various components of diversity are calculated, and the other arguments, the whole theory evaporates.

Richard Sproat said,

April 17, 2011 @ 4:59 pm

[(myl) For there to be a "serial founder effect" in "phonological diversity", it would have to be true that in the homeland, there's enough contact (with other dialects, related languages, or entirely different languages) for phonetic innovation to spread via diffusion (just as gene flow spreads mutations in the homeland's gene pool), while in a situation of migration into relatively empty territory, this process of diffusion (of both genes and memes) stops.]

Fair enough. (And by the way this is not unrelated to a point I made in my review of the paper for Science, namely that one possible explanation for the Hay-Bauer correlation, assuming it's real, is that larger languages have more chance for dialectal variation and thus more variation than small languages.)

But in any case even if the sources of phonemic diversity are indeed lost with an initial band of migrants, once the population grows and they come in contact with other languages — something that clearly happened time and again over the last 50-70K years, there's ample opportunity to gain all that diversity back.

[(myl) Yes, this seems to be the weakest part of the argument. Given what we can observe about the rate of phonetic innovation and phonemic splits in recorded history, it seems implausible that a 'serial founder effect" in phonological inventories could have lasted so long.]

PL Monteiro said,

April 17, 2011 @ 5:05 pm

The graph of Total Phoneme Diversity by Region (second graph), may have a misleading ordering: if we put Oceania (mostly New Guinea) before North and South America, and further question if Europe should not come before Asia, the whole effect breaks down.

Further, the first graph, seems to get the slope from a first cluster of data points up (perhaps Sub-Sahara Africa), and a second cluster down (perhaps India? or South East Asia). Languages considered in groupings of family, culture or contact, in what you describe as an alternate explanation to the results in your reply to GeorgeW, as "a combination of 'locality of related languages' and 'contact phenomena'," would bring the number of real data points to half a dozen.

Now if only Dave Barry was available for comment ;-).

[(myl) Perhaps he would echo Donald Rumsfeld: "You go to WALS with the phonemes you have…"]

German Dziebel said,

April 17, 2011 @ 6:24 pm

@myl

"[(myl) I'm not at all sure that Africa does have fewer family-level linguistic groups than other areas. It happens that Joseph Greenberg, a well-known lumper, has persuaded most people to accept his (strongly lumped) classification of African languages. But several of the family groups, such as West Atlantic, have little or nothing to hold them together except for geographical proximity and a few shared features that might well have been borrowed.]"

Even after Greenberg's legacy in Africa has been corrected, there are only 20 language families there. See Language Ecology and Linguistic Diversity on the African Continent, by Gerrit J. Dimmendaal (2008). This is compared with 140 stocks in the New World.

@Teo

"What if they had used S, O & V orderings? Surely, the number of orderings and patterns found outside South America is a subset of those found there. So?"

There are many features of Amerindian languages, cultures and kinship structures just like your word order example that suggest that an out of America theory is at least just as likely as out of Africa. I outlined the former in "The Genius of Kinship: The Phenomenon of Kinship and the Global Diversity of Kinship Terminologies" (2007).

marie-lucie said,

April 17, 2011 @ 8:50 pm

GD: Even after Greenberg's legacy in Africa has been corrected, there are only 20 language families there. … . This is compared with 140 stocks in the New World.

These statements assume that the definitions of "families" and "stocks" (normally a higher level classification than "families") are correct in every case. In fact those words are often used very loosely. I can't comment about the African situation, but 140 "stocks" for the Americas is a ridiculously large number, while Greenberg's "Amerind family" which encompasses most of those "stocks" is a gross exaggeration.

Sigga said,

April 18, 2011 @ 5:48 am

I'm mostly just upset they have a dot on Greenland but nothing on Iceland. Sure we're small but we exist!

James Wimberley said,

April 18, 2011 @ 1:01 pm

As a student of Professor Barry, I'd like to submit a hypothesis that explains the geographical distribution of tones in ML's pretty map more economically than out-of Africa. Tonal languages are in the tropics. In higher latitudes, everybody has a cold in winter, so tones become impracticable. A-choo.

marie-lucie said,

April 18, 2011 @ 2:06 pm

North China is not in the tropics, and neither are Alaska and the Canadian Northwest Territories, among other locations with tone languages.

[(myl) And the Germans, among other inhabitants of temperate climes, seem able to sing at all times of year without let or hindrance. It would be an unusually selective upper-respiratory infection that wiped out lexical tone but left lieder intact.]

ohwilleke said,

April 18, 2011 @ 5:37 pm

There are specific classes of phonemes where the serial founder effect theory makes some sense. Click consonants probably were found in the proto-Eurasian population, nor probably were labial-velar consonants, and neither of those were reinvented in large, influential populations elsewhere. Frictive consonants probably were lost in the founding populations of Australia and New Zealand. The distinction between nasal and non-nasal vowels may have been an African feature that didn't leave the continent and was reinvented only rarely elsewhere. One can imagine phyrangeal consonants originating in East Africa and not making it much beyond the Caucasus. These are probably the signals that drive the trend.

But, there are also many phonemic features that don't show this kind of trend. The loss of just some frictive consonants doesn't seem to remove any of them from the available set of down the line linguistic innovations. The "th" sound's distribution looks like it was independently developed in many places. The Amazonian area shows innovations that can't be explained by serial founder effects, nor generallly, does the pattern of tone systems and the number of vowels in a language.

Wimberley may be incorrect in his "a-choo" supposition, but he is surely right in observing that high latitudes and deserts have far fewer vowels and are far less prone to have tonal languages than moist places in lower latitudes, a trend that describes these data sets much better than the distance from Africa theory. If one wanted to tell an evolutionary biologist just so story, one could reason that people in moist warm places have far more dense bird songs to listen to to survive and understand their environment, and that being attuned to bird calls makes language innovation that uses similar sounds more natural. One could come up with other "just so stories" as well. But, the fact that latitude and humidity better explain the trend than a serial founder effect or distance from Africa, which is a poor fit for vowel inventory or tone system presence and add a lot of noise to the data in support of Atkinson's theory is a fact.

Arjan said,

April 18, 2011 @ 6:05 pm

And still, the number has not yet been adequately reduced by convincingly relating the recognized families and isolates. No doubt the number will be reduced in the future, but (except for some recent proposals) the counts are around 75 lineages for North and Central America (1), and 117-118 for South America (2,3) – with hardly any overlap.

(1) Campbell, Lyle, and Marianne Mithun. 1979. The Languages of Native America: Historical and Comparative Assessment. Austin: University of Texas Press.

(2) Loukotka, Čestmír. 1968. Classification of South American Indian languages. Los Angeles: Latin American Center, UCLA.

(3) Kaufman, Terrence. 1990. Language History In South America: What We Know and How to Know More. In Amazonian Linguistics: Studies in Lowland South American Languages, ed. Doris L. Payne, 13-73. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Richard Sproat said,

April 18, 2011 @ 9:22 pm

@ohwilleke

[The distinction between nasal and non-nasal vowels may have been an African feature that didn't leave the continent and was reinvented only rarely elsewhere.]

Eh? Let's see just off the top of my head I can think of French, Portuguese, Breton, Polish (I think), Athabaskan languages, various South American languages including Piraha, Shanghainese, all of which have nasal/non-nasal vowel distinctions apparently independently developed. (Well Breton may plausibly have borrowed that from French.) Doesn't seem that rare to me.

marie-lucie said,

April 18, 2011 @ 9:54 pm

Nasal vowels are not rare at all. Phonetically nasal vowels typically arise as allophones of oral vowels before nasal consonants (compare the vowels in English can and cat) and if there is subsequent loss of the nasal consonants, the nasal vowels become phonemic. (English can't, want and don't are commonly pronounced with nasal vowels before the t, not before the n, which is lost, but these examples are too isolated to result in a phonemic reinterpretation).

Dw said,

April 18, 2011 @ 10:58 pm

The "th" sound's distribution looks like it was independently developed in many places

Even within Indo-European, a "th" sound is known to have developed independently in Germanic (surviving in English and Icelandic), Greek, Avestan and Castilian Spanish.

German Dziebel said,

April 19, 2011 @ 8:02 am

@marie-lucie

"140 "stocks" for the Americas is a ridiculously large number, while Greenberg's "Amerind family" which encompasses most of those "stocks" is a gross exaggeration."

Even if the truth is somewhere in the middle (although undocumented language extinction in the Americas after 1492 is another thing to consider), linguistic diversity in the Americas is at odds with the serial bottleneck theory advanced by geneticists. Nor is it consistent with 12-15,000 years time horizon for the peopling of the Americas suggested by archaeologists.

PL Monteiro said,

April 19, 2011 @ 1:31 pm

My point is that, independently of the huge amount of obfuscating detail we throw into it, the slope in the graph seems to be just the spurious result of just two major cultural groupings of languages.

This is not so much a consequence of the necessity to work with what we have. It is more the artifact of applying sophisticated mathematical methods to obscure, in ways very difficult to see through, either Mickey Mouse results or propositions untenable on analysis.

Fact driven studies tend to progress building on each other. Studies of the future will rely on studies done today, just like studies today refer to studies produced before. If our methods or data today do not warrant some conclusion, shouldn't we refrain from claiming it? If we do, we are no longer doing fact driven studies, I think.

Bill Walderman said,

April 19, 2011 @ 1:42 pm

"North China is not in the tropics, and neither are Alaska and the Canadian Northwest Territories, among other locations with tone languages."

Not to mention Swedish and Norwegian.

Damon said,

April 19, 2011 @ 4:30 pm

It's too bad people have raised so many objections to this, because it's such an interesting idea. As Agent Mulder used to say, I want to believe.

I've always had this half-assed theory that something like this was in play in the Austronesian languages, because it seems like you get fewer and fewer possible syllables as you trace their expansion through the Pacific step-by-step. But I've never even tried to really verify if it's true. It just sort of seems like it is.

PL Monteiro said,

April 19, 2011 @ 7:55 pm

@ Damon: I can't see why your idea is unworkable or dependent of a global out of Africa plot that we can't be certain about. Picking up islands individually, and the languages spoken in those islands, trying to see if there is a pattern that emerges, that is pretty fact driven to me.

kip said,

April 22, 2011 @ 1:52 pm

I'd like to see the correlation between absolute value of latitude and total phenome diversity. I suspect that the correlation would be even stronger than the distance from Africa correlation.

Florian Blaschke said,

April 26, 2011 @ 5:49 pm

I'm no Africanist, but from what I've read and heard, any conclusion that there are only, say, 20 genetic units in Africa seems quite premature. There are lots of understudied languages (and families!) in that continent, or languages only known from wordlists, if at all. In the past, Africanists were quick to assign little-known languages and even families to larger groupings, on typological, ethnic, racial or simply geographical grounds, glossing over such lack of data. Roger Blench has specifically pointed out a couple of scattered obscure languages mostly in West Africa and thereabouts whose classification is not at all clear and that actually seem to be isolated. But even some families that are so small that you would think they should be easy to demonstrate, or even reconstruct, are not even firmly demonstrated at all. I remember these comment: http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=980#comment-17543 and http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=980#comment-17592. (I tried to link to it using HTML, but the href command didn't seem to like the question mark. Weird.)

If we add up all isolated, unclassified or insufficiently securely classified languages and smaller families, who knows how high the number of genetic units in Africa rises. And that's just counting languages that are mostly still spoken (if barely), or have recently (20th century) gone extinct. I'm disregarding Meroitic or obscure ancient North African languages, and not even talking about what may have gone extinct in more recent centuries. It's well possible that the genetic linguistic diversity of Africa is quite underestimated, and that there is still too much lumping going on.

This makes me wonder why we should give more credence to Greenberg's results in Africa than in the Americas; after all, they were arrived at using the same, heavily controversial, method. Perhaps Africa is not all that different from America, despite the effects of the Bantu and other such expansions (Arabic, for one).

I'm fairly clueless about South America as well, so I have to resort to Wikipedia, which talks about Macro-Je, but also about a proposal linking this one to Tupi and Carib, based on irregular morphology. Which sounds much more interesting than most proposals linking well-known, large and geographically widespread language families. Interestingly, looking at the accompanying map, I get the distinct impression that a possible proto-Je-Tupi-Carib would have radiated out of a centre at the mouth of the Amazon.

Seems every continent/macro-areal has its mega-families: Trans-New Guinea in New Guinea, Pama-Nyungan in Australia, Uto-Aztecan, Algic and Athabascan-Eyak-Tlingit in North America, Oto-Manguean in Mesoamerica, Indo-European and Uralic in Eurasia, Austro-Asiatic and Sino-Tibetan in East Asia, Austronesian in Oceania, in addition to a proliferation of smaller families and isolates, which would, again, make Africa thoroughly unexceptional. Probably not even unexpected. Of course, if Africa is the centre of dispersion of humanity's languages, you might expect it to look more like the Americas than it does, without any family dominating the continent as clearly as Bantu does (but then, that's true only for the southern half), but then, Africa would have had many millennia more time than the Americas for such a thing to happen. Also, typologically speaking, Africa is clearly exceptionally diverse, even within families (possibly reflecting, albeit indirectly, absorbed earlier diversity), and I might add that the major areal groupings among themselves are radically different from each other, not to be outclassed by the Americas.

Therefore, I do not think that the conclusion that Africa is "too undiverse" to be the cradle not only of humanity, but also its languages, is justified.

Alan said,

April 27, 2011 @ 9:07 pm

I'm not going to read it again right now, but my recollection is that the author doesn't explain in what way he thinks language evolves, and there are a lot of comments on here expressing confusion about that. I don't know whether this is exactly the theory he had in mind, but it's worth considering:

Christiansen, M. H., & Chater, N. (2008). Language as shaped by the brain. The Behavioral and brain sciences, 31(5), 489-508; discussion 509-58. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X08004998.

Language evolves on its own, it's not (necessarily) based on a genetic metaphor.

In small populations the rate of evolution increases because it is easier for mutations to spread throughout the population and become fixed. It would follow that during bottlenecks you are likely to find a decrease in diversity. It's possible that this kind of dynamic holds of things like phonemes. The evolution of language in this sense is sensitive to the population size of speakers, but it is not a straightforward (and horribly flawed) analogy to genetic evolution. Language may very well constitute its own evolutionary system.

Was the Tower of Babel in Africa? « The Chameleon's Tongue said,

April 27, 2011 @ 10:54 pm

[…] will be weighted unfairly, argues Mark Liberman from the University of Pennsylvania. He points out, in his post on Language Log, that while all languages have vowels and consonants, tones are rarer. Only some regions of the […]

German Dziebel said,

May 11, 2011 @ 5:08 am

@Florian Blaschke

20 language stocks in Africa already reflects a post-Greenbergian state of African language classification. Greenberg lumped all African languages into only 4 genetic groups: Niger-Congo, Nilo-Saharan, Khoisan and Afroasiatic.

"If we add up all isolated, unclassified or insufficiently securely classified languages and smaller families, who knows how high the number of genetic units in Africa rises. And that's just counting languages that are mostly still spoken (if barely), or have recently (20th century) gone extinct."

This is true of the New World, maybe even more so than of Africa.

"Of course, if Africa is the centre of dispersion of humanity's languages, you might expect it to look more like the Americas than it does, without any family dominating the continent as clearly as Bantu does (but then, that's true only for the southern half), but then, Africa would have have had many millennia more time than the Americas for such a thing to happen."

This would be true under the assumption, per Dixon, that languages tend to gravitate toward uniformity over time due to contact. This assumption remains unproven – see Claire Bowern's critique of Dixon – and somewhat teleological. On the other hand, recent genetic history shows that the argument that greater diversity indicates greater age is falsified in places like the New World post 1492. The influx of genes from all continents has made the New World the continent of highest diversity, but the origin of this diversity is most recent. The same may be true of Sub-Saharan Africa prior to 1492: populations simply continued to aggregate over the millenia (agricultural and pastoralist gene flow into foragers are the most recent attested processes of genetic hybridization). Correspondingly, linguistic diversity has gone down first in Sub-Saharan Africa and most recently in the New World.

So, genetic and linguistic diversity work on cross-purposes and aren't isomorphic with each, contrary to what the paper assumes. Consequently, America could be considered the center of human dispersals for a wrong reason (highest post-1492 genetic diversity) and for a good reason (highest pre-1492 linguistic diversity), if we keep one master, cross-disciplinary assumption, namely that diversity is always positively correlated with age.

Link love: language (29) « Sentence first said,

May 15, 2011 @ 3:25 am

[…] diversity and language origins: abstract; discussion and criticism from Language Log, Richard Sproat, Language Hat, The Economist, and Nicholas […]

Before Babel? « Panther Red said,

August 14, 2011 @ 11:22 pm

[…] mention only the two posts about it that appeared on the incomparable Language Log, Mark Liberman analyzed Atkinson's methodology, and Sarah Thomason reproduced a letter that anthropologists Ives […]

rbanerjee said,

February 1, 2012 @ 3:12 pm

articulation maps may reveal much interesting structure as compared to this coarse study.

sub saharan africa south asia australia and western europe may share an older kinship disrupted by a levantine east/southern european component.

Rory Van Tuyl said,

February 9, 2012 @ 6:31 pm

Science Magazine has, at long last, published three "Technical Comments" in response to Atkinson's original article. All are unstinting in their criticism of his paper "“Phonemic Diversity Supports a Serial Founder Effect Model of Language Expansion from Africa” Science 15 April 2011, p. 346.

To view these detailed critiques, go to:

http://www.sciencemag.org/content/current#TechnicalComments

Replicated Typo said,

March 6, 2012 @ 1:37 pm

[…] Atkinson's (2011) paper on a serial founder effect is criticised (although not as tough as some other responses), but the authors suggest that "Regardless of the outcome of this debate, […]

Dan S said,

August 28, 2012 @ 12:56 pm

In case I'm not the only one to come back to this posting on the basis of the LL discussions of Atkinson's more-recent article in Science on PIE origins, here's a still-working link to the three critiques mentioned above by Rory Van Tuyl, plus a response by Atkinson, all of it freely accessible:

http://www.sciencemag.org/content/335/6069.toc#TechnicalComments

Florian Blaschke said,

November 10, 2012 @ 1:57 pm

@German Dziebel:

I know. Still, if African linguists were as conservative as American linguists, and equally prone to splitter tendencies, the number of acknowledged genetic units in Africa would be several times more than 20. Keep in mind the comments I linked to, which indicate that the evidence even for relatively low-level groups is often tenuous.

Note that I am firmly on the side of the splitters, and that I am extremely sceptical of the conclusions from this study and other studies by Atkinson.

Das egoistische Phonem – Sprachlog said,

December 12, 2012 @ 2:12 pm

[…] nicht unproblematisch (Mark Liberman hat das im Language Log vor einigen Tagen ausführlich diskutiert). Wahrscheinlich wäre es besser, die Berechnung separat für jeden dieser Aspeke durchzuführen, […]

What do I really, really love West African languages? | said,

April 29, 2013 @ 5:06 pm

[…] how did these language get so cool? Well, there's some evidence that these languages have really robust and complex sound systems because the people speaking them […]

I once knew a guy named Anatoly who had a bicycle… does that count? | Rated Zed said,

July 8, 2013 @ 1:00 am

[…] were the marks of "phonemic diversity" used and are they appropriate (Mark Liberman noted that tonal diversity seems to be being over-weighted and as a result places where tonal languages […]