How powerful is sisterhood?

« previous post | next post »

Yesterday, the "most viewed" and "most emailed" item on the New York Times website was Deborah Tannen's essay, "Why Sisterly Chats Make People Happier", which opens this way:

"Having a Sister Makes You Happier": that was the headline on a recent article about a study finding that adolescents who have a sister are less likely to report such feelings as "I am unhappy, sad or depressed" and "I feel like no one loves me."

These findings are no fluke; other studies have come to similar conclusions. But why would having a sister make you happier?

The usual answer — that girls and women are more likely than boys and men to talk about emotions — is somehow unsatisfying, especially to a researcher like me. Much of my work over the years has developed the premise that women's styles of friendship and conversation aren't inherently better than men's, simply different.

Prof. Tannen goes on to give some of the reasons that she finds "the usual answer … somehow unsatisfying", and her thoughts deserve the attention that NYT readers gave them. But I was curious about the power of sisterhood, whether it might come from "styles of friendship and conversation" or from something else, and so I took a look at the recent study that she links to: Laura Padilla-Walker et al., "Self-regulation as a mediator between sibling relationship quality and early adolescents' positive and negative outcome", Journal of Family Psychology, 24(4): 419-238, 2010.

There's a lot to like about this study. For example, the authors worked with a large sample that was not limited to undergrads in a psych department's subject pool — an on-going longitudinal study of nearly a thousand children in a demographically balanced set of nearly 400 families.

The dependent variable that they used to measure "(un)happiness" was self-report of what they call "internalizing behaviors":

Externalizing and internalizing behaviors were assessed at Time 1 and 2 from a measure taken from the Youth and Family project assessing antisocial behavior (9 items) and depression/anxiety (13 items). Sample items for externalizing include, "I lie or cheat" and "I steal things from other places than home;" and for internalizing include, "I am unhappy, sad, or depressed" and "I feel that no one loves me." Participants answered these items in regard to the adolescent's behavior on a scale ranging from 0 (not true) to 2 (very true or often true).

Unfortunately, the authors give us only a highly digested form of the results. We don't get the raw tables of independent and dependent variable values — a row for each child, with demographic variables including sibling(s) sex along with that child's measure of "externalizing and internalizing behaviors". We don't even get mean values and standard deviations for the "internalizing behaviors" measure among sisterful and sisterless children (unless I managed to read past them). Instead, we get the "betas" (standardized regression coefficients) and associated significance levels from an SPSS AMOS "path analysis":

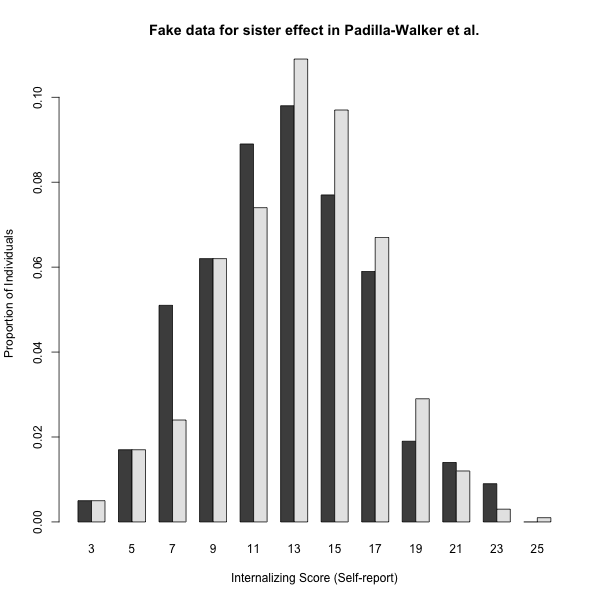

So in order to give you a more concrete idea of what the beta=-0.13 (connecting Sibling Gender to Internalizing Behavior in two-parent families) and beta=-0.12 (for the same connection in single-parent families) might mean, I created some fake data (by running the obvious regression equation as a generator). A histogram from a typical run looks like this:

For this particular set of fake data, the standardized regression coefficient for predicting "internalizing score" from presence of absence of a sister is -0.128, significantly different from 0 at the p<.05 level, just as in the authors' analysis of the real data. The mean internalizing score for the 500 "children" with sisters is 13.11, and the mean score for the 500 "children" without sisters is 12.60. (Recall that these scores are the result of summing the answers to 13 questions like "I feel that no one loves me" on a three-point scale, "from 0 (not true) to 2 (very true or often true)". So -0.51 — the average effect of having a sister — might be interpreted as meaning that half of the sisterful respondents lowered their response to one of the 13 questions by one unit.)

Pearson's r for the correlation between sisterlessness and unhappiness is 0.0638, so the proportion of variance (in "internalizing score") accounted for by having a sister is r^2 = .004.

(The difference in mean values in the true experimental data might have been larger or smaller than this, and the actual percent of variance accounted for might have also been larger or smaller. I's not possible to tell from the information given in the paper, as far as I can see, though I'd be surprised if the truth were radically different from this simulation, which represents the results of my first guess about what some fake data with the observed normalized regression coefficients might look like.)

These fake results, like the real results, are statistically significant — but how meaningful are they?

The answer depends on why you want to know. If you want to know why you're so (un)happy, then not very much of the answer can be expected to depend on whether or not you have any sisters. One way to express this in an intuitive way is to observe that if we randomly pick from this (fake) distribution a child with sister(s) and a child without, the sisterful child will have a lower "internalizing" score — report themselves as less depressed — about 53% of the time. 47% of the time the sisterless child will be happier on this measure.

This is a long way from the statement that "Adolescents with sisters feel less lonely, unloved, guilty, self-conscious and fearful", which is how ABC News characterized the study's findings, or "Statistical analyses showed that having a sister protected adolescents from feeling lonely, unloved, guilty, self-conscious and fearful", which is what the BYU press release said. At least, if you take predications about generic plurals ("A's are X-er than B's") to be statements about typical members of the groups involved, then such statements are false. On the other hand, such statements are true if you take "A's are X-er than B's" to mean simply that a statistical analysis showed that the mean value of a sample of X's was higher than the mean value of a sample of Y's, by an amount that was unlikely to be the result of sampling error.

Unfortunately, I think that most people interpret general statements about generic plurals as claims about typical members of the groups involved — even when the sentences are hedged with statistics-talk like "tend to" or "are less likely to". In this particular case, the results of misunderstanding are probably harmless or even beneficial — no doubt thousands of NYT readers were motivated to have sisterly chats, and even some of the sisterless may have thought to look around for an honorary sister or two, which is surely all to the good. The fact that the misinterpretation reinforces a commonly-held stereotype is part of the reason for the enthusiastic uptake. But not all commonly-held stereotypes — and not all generic plural statements by scientists — are so benign.

Jonathan Badger said,

October 27, 2010 @ 6:50 pm

Of course, even ignoring the small statistical difference, I'm not very convinced that self-reported measurements of "happiness" based on those types of "internalizing behaviors" surveys are very informative — they remind me of those personality surveys you have to take at some job interviews — half the time I don't even know what the correct answer is for me and I just pick one to get on with it.

John Cowan said,

October 27, 2010 @ 8:12 pm

""I have heard it said that all foreigners will do anything for gold. I am glad to see it is not so."

"Any saying that claims all of some group will do a particular thing is not to be trusted," Park observed.

"Spoken like a judge."

—Harry Turtledove, "The Pugnacious Peacemaker"

Michael Watts said,

October 27, 2010 @ 8:36 pm

Do these studies showing a positive effect of having a sister control for number of siblings? In a world where small numbers of children are the norm, it seems easy to confuse "has a sister" with "has a sibling" ; might that be (part of) the effect?

[(myl) They appear to have controlled for such things in an appropriate way.]

Robert said,

October 27, 2010 @ 11:03 pm

"Any saying that claims all of some group will do a particular thing is not to be trusted."

I couldn't help but be reminded of Lagrange's theorem. Never mind.

Will said,

October 28, 2010 @ 2:27 am

You know, having grown up with many siblings, including an older sister, I do intuitively feel like I'm about 5% happier for it. I think the study is spot on, even if it is misinterpreted by some media outlets.

D.O. said,

October 28, 2010 @ 2:46 am

Maybe its too late now, but I do not see which type of bars represent "sisterless fakes" and which one "sisterfull fakes". It is all to the good, because I am unable to decide it just from the graph itself — another proof that the difference is very small.

D.O. said,

October 28, 2010 @ 2:51 am

Given it another look, I think lighter bars are sort of more to the right and the darker ones are sort of to the left. So the lighter ones have to be "sisterless". It might be another test of significance — whether and how many people can tell the difference by just looking at the graph of a distribution.

Rubrick said,

October 28, 2010 @ 3:26 am

I cannot tell if Will is making a rather subtle (and actually quite funny) joke or not.

GeorgeW said,

October 28, 2010 @ 5:44 am

@Rubrick: I am confident that Will is quite serious as I have two sisters and am 11.8743% happier as a result.

Diane said,

October 28, 2010 @ 7:39 am

I was struck that the author went out of her way to insist that any benefit to having sisters is not about women's communication style. I would never have thought it was. My uninformed guess would be that women are better at building a sense of family and people are happier when they feel more connected to a group.

Certainly that is true in my own family. My sister and I do a lot more for the family than our brothers do. We call our brothers and our parents more frequently than they do, we (with our mom) plan the family holiday celebrations, we're the ones who remember to buy flowers for our parents' anniversary,etc. Can't speak for my sister, but I do these kinds of things consciously and deliberately because I think they're necessary to keep the family close.

But then, I am allergic to talk of the virtues of "women's communication style" because it is just about opposite to the way I am. Nice to know there's not something wrong with me because I don't communicate like the typical woman!

Nijma said,

October 28, 2010 @ 10:08 am

In many families it is the women who do the social planning. If I want to know when my brother will travel, say, for a holiday, the fastest way to find out is to call my mother, who will have talked to his wife, who keeps track of all their school, doctor, and children's appointments. Even if I could get through all the electronic devices that shield my brother from his telephones, he would be unlikely to give me an answer without checking with her.

I'm not sure a sister-in-law can substitute for a sister though. Since my brother got married, I would say I have become only about 1.5% happier.

Ginger Yellow said,

October 28, 2010 @ 11:05 am

The usual answer — that girls and women are more likely than boys and men to talk about emotions — is somehow unsatisfying, especially to a researcher like me. Much of my work over the years has developed the premise that women's styles of friendship and conversation aren't inherently better than men's, simply different.

This seems like a bit of a non-sequitur. Assuming for the sake of argument that the "usual answer" is correct, that doesn't lead to the conclusion that "women's styles of friendship and conversation [are]inherently better". They could be better at alleviating depression, but worse in other ways (mooching, to give a made up example).

groki said,

October 28, 2010 @ 1:13 pm

of course it's helpful having someone as sister: she's one who assists!

J. Goard said,

October 30, 2010 @ 12:40 am

This study is totally bogus. When I was a baby, I was 93.7% happy: no school, no work, just fingerpainting all day and crapping right in my own pants with someone to clean it up for me! Then I got a sister, and since then, just look at all this tedious responsibility… doing my best to slack off now, and I'm still barely breaking 70%. Where's my latte, damn it?

Around the Crib | Savage Minds said,

December 14, 2010 @ 11:42 pm

[…] Language Log responds to a NYT piece on linguist Deborah Tannen's current research on why having a sister makes you happy. […]