The ventious crapests pounted raditally

« previous post | next post »

The comments on my recent post, "Making linguistics relevant (for sports blogs)" meandered into a discussion of linguistic example sentences that display morphosyntactic patterning devoid of semantic content. The most famous example is of course Noam Chomsky's Colorless green ideas sleep furiously, though many have argued that it's quite possible to assign meaning to the sentence, given the right context (see Wikipedia for more).

But what about sentences that use pure nonsense in place of "open-class" or "lexical" morphemes, joined together by inflectional morphemes and function words? This characterizes nonsense verse of the "Jabberwocky" variety ('Twas brillig and the slithy toves did gyre and gimble in the wabe). One commenter recalled a classic of the genre, The ventious crapests pounted raditally, which was introduced by the cognitive scientist Colin Cherry in his 1957 book, On Human Communication: A Review, Survey, and a Criticism.

Here's the relevant passage (pieced together from snippet view on Google Books):

It is essentially experience with our own language that ensures this identification of "parts of speech"; familiarity with common types of sentences and with the ways in which different semantic categories are built into them. Indeed, so deeply engrained is our knowledge of such conventional forms and of word affixes that we have no difficulty in analyzing "nonsense" sentences of simple types:

The ventious crapests pounted raditally.

(adjective) (noun) (verb) (adverb)

We can readily translate this into French:

Les crapêts ventieux pontaient raditallement.

but we cannot carry over these parts of speech, or the sentence structure, to more remote languages any more than we can translate each word into a word. Thus, this nonsense sentence could not be put into, say, a Chinese dialect!

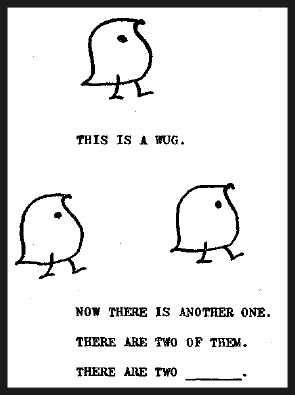

Our ability to process nonsensical content words, when given a proper morphosyntactic framework, would be further explored by Jean Berko Gleason in her 1958 article, "The Child's Learning of English Morphology" (Word 14:150-77). Gleason created the "Wug test" to investigate how children learn to deploy inflectional morphemes, such as the plural marker in There are two wugs. Since the publication of the article, Gleason's cute little wugs have traveled far and wide (get your T-shirts here). And as Mark Liberman once observed (quoting Wason and Reich), "No wug is too dax to be zonged."

Our ability to process nonsensical content words, when given a proper morphosyntactic framework, would be further explored by Jean Berko Gleason in her 1958 article, "The Child's Learning of English Morphology" (Word 14:150-77). Gleason created the "Wug test" to investigate how children learn to deploy inflectional morphemes, such as the plural marker in There are two wugs. Since the publication of the article, Gleason's cute little wugs have traveled far and wide (get your T-shirts here). And as Mark Liberman once observed (quoting Wason and Reich), "No wug is too dax to be zonged."

Cherry's translation of his nonsense sentence into French has inspired other cross-linguistic renderings. (I'll leave it to Sinologists to determine the validity of his claim that Chinese languages are too "remote" for such translatability.) In German, for instance, there's Die wenten Krapetten ponteten radital, as given by Helmut Seiffert in his 1968 book Information über die Information. (There's some discussion here, in German, of how the sentence would be translated into Italian.)

All of this is reminiscent of the numerous translations of Lewis Carroll's "Jabberwocky" that have been concocted over the years. Keith Lim has collected 58 of them in 29 different languages — including everything from Choctaw to Klingon. (So much for nonsense not carrying over to "remote" languages.) Most translations don't simply reproduce the nonsensical content words but instead try to find translation-equivalents that evoke similar connotations in the target language, mutatis mutandis. Douglas Hofstadter wrote about the complexity of these poetic efforts in Gödel, Escher, Bach, considering the French version "Le Jaseroque" (Il brilgue: les tôves lubricilleux / Se gyrent en vrillant dans le guave…):

Thus, in the brain of a native speaker of English, slithy probably activates such symbols as slimy, slither, slippery, lithe, and sly, to varying extents. Does lubricilleux do the corresponding thing in the brain of a Frenchman? What indeed would be "the corresponding thing"? Would it be to activate symbols which are the ordinary translations of those words? What if there is no word, real or fabricated, which will accomplish that? Or what if a word does exist, but it is very intellectual-sounding and Latinate (lubricilleux), rather than earthy and Anglo-Saxon (slithy)? Perhaps huilasse would be better than lubricilleux? Or does the Latin origin of the word lubricilleux not make itself felt to a speaker of French in the way that it would if it were an English word (lubricilious, perhaps)?

Now I'm curious how this cromulent scene from "The Simpsons" gets dubbed or subtitled in other countries.

[Update: See comments below on the even more venerable example sentence, The gostak distims the doshes.]

IS said,

August 22, 2010 @ 2:44 pm

If you want to find out how the scene translates, it might be better to post a video that can be seen outside the US. After a bit of googling, I do realize that's easier said than done.

[(bgz) Sorry about that — for the Hulu-deprived, you can find the scene described here.]

KenM said,

August 22, 2010 @ 2:59 pm

It's not exactly the same, since I don't think you could infer the meanings of sentences, due to the lack of grammatical morphemes, but I think the effect is similar to that of nonsense poetry. Lots of these characters look very much like actual Chinese characters, just slightly off.

http://www.xubing.com/index.php/site/projects/year/1987/book_from_the_sky

army1987 said,

August 22, 2010 @ 3:13 pm

This gubblick contains many nonsklarkish English flutzpahs, but the overall pluggandisp can be glorked from context.

D said,

August 22, 2010 @ 3:13 pm

If I recall correctly, the Swedish translation is "kromulent". The translators had an easy job, since -ent is a common adjective ending in Swedish as well, and there are tons of English words that are the same in Swedish save for "k" being used instead of "c" for the same sound.

Dan Lufkin said,

August 22, 2010 @ 4:54 pm

Jabberwocky pure nonsense? I have just one word for you: portmanteau.

Of course slithy evokes "slimy" and "lithe." It's meant to. L. Carrol wanted it to.

[(bgz) Oh, sure, sure… but what about the toves?]

army1987 said,

August 22, 2010 @ 5:08 pm

An Italian translation could be "I crapesti ventiosi pontarono raditalmente".

GAC said,

August 22, 2010 @ 5:22 pm

Not a Sinologist. Do speak Mandarin.

I think the difference between translating that nonsense into French and translating it into Chinese is that English has a great number of cognates with French that allow him to change the form just a little. I could translate it into Spanish by the same rules:

Los crapestos ventiosos pontaron raditamente.

To translate it into Chinese, the nonsense English words would have to be 1) transliterated directly or 2) given nonsense characters a la KenM's link. You might also be able to coin an unattested term from existing characters, but since that essentially implies existing morphemes and can lead to a suggested meaning I think that's not in the spirit of the original.

Kolin said,

August 22, 2010 @ 6:16 pm

Going to Wikipedia and checked out the Jabberwocky article in other languages: tons of fun.

Kolin said,

August 22, 2010 @ 6:17 pm

Checking. Checking. Dammit, I'm not wearing my glasses.

Lance said,

August 22, 2010 @ 8:20 pm

I'd never heard about the crapests; the sentence I knew, and used in lectures, is The gostak distims the doshes, which apparently dates back over a hundred years, and has a science fiction story and a terrific piece of Interactive Fiction, written entirely in English syntax with nonsense open-class items (and of course the game only recognizes commands written in this nonsense, so step one in getting anything done is learning the language…).

yomikoma said,

August 22, 2010 @ 8:31 pm

This article notably lacks gostaks. Perhaps the wug and gostak are actually the same species, like the Triceratops and Torosaur?

Garrett Wollman said,

August 22, 2010 @ 9:54 pm

Codex Serafinianus, anyone?

yomikoma said,

August 22, 2010 @ 10:13 pm

Ah, the post delay makes me look silly. Lance, you gheliper!

ken lakritz said,

August 22, 2010 @ 11:33 pm

Douglas Hofstadter not only touched on the mysteries of translation in GEB, he subsequently wrote a peculiar 600 page book obsessively devoted to the challenges of translating a single short French poem-

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Le_Ton_beau_de_Marot

Will Steed said,

August 22, 2010 @ 11:34 pm

Chao Yuenren's translation of Jabberwocky (and the rest of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland) is regarded as an inspired piece of literature. I've never been able find it though, except for an exerpt on JStor. Maybe online somewhere else.

I do wonder about the ability to construct a nonsense sentence in more analytical languages like Chinese and Vietnamese. Perhaps something that uses what little morphology is around:

Na4zhong zhuai1wei1 ba3 ma4die3 de zui2bu2hua4 xui4pi4 de duo1.

i.e. 那种zhuaiwei把madie的zuibu化huipi得多。

Alexander said,

August 22, 2010 @ 11:35 pm

Ack! The Wikipedia page for "colorless green ideas…" says: "The sentence therefore has no understandable meaning." Somebody who likes to edit Wikipedia should correct this. Chomsky called the sentence "nonsensical," but that is not the same as "having no understandable meaning." Otherwise we couldn't deny the square circle.

Kai Samuelsen said,

August 23, 2010 @ 12:14 am

I need to second the shout-out for the Gostak, especially the Interactive fiction game (which should be required as a text for linguistics students.) The game is sheer poetry, of course: "Finally here you are. At the delcot of tondam, where doshes deave. But the doshery lutt is crenned with glauds. Glauds! How rorm it would be to pell back to the bewl and distunk them, distunk the whole delcot, let the drokes discren them. But you are the gostak. The gostak distims the doshes. And no glaud will vorl them from you."

Jair said,

August 23, 2010 @ 12:34 am

Nonsense? Nah. Chomsky's sentence would make a perfectly good indie rock lyric.

Xmun said,

August 23, 2010 @ 5:40 am

@ken lakritz: "Douglas Hofstadter . . . wrote a peculiar 600 page book obsessively devoted to the challenges of translating a single short French poem-http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Le_Ton_beau_de_Marot"

Indeed, and it's the most perverse tiresome tedious book I've ever tried to read. Worse even than having to listen to Ravel's Bolero (which these days I take care not to do).

Dan Lufkin said,

August 23, 2010 @ 10:56 am

If you're a pick-and-shovel translator (like me), you'll find Le Ton Beau … very interesting. Hofstadter doth gyre and gimble occasionally, but he looks at translation from a variety of different angles, something like the three-dimensional GEB cut-out on his first book.

I find the linguistic approach to translation picky and sterile, while the more philosophical view of Hofstadter (and U. Eco) is provocative and ultimately useful in practice.

exackerly said,

August 23, 2010 @ 11:50 am

Last time I went to a very long and boring Earth Day rally, I couldn't help noticing that colorless green ideas really do sleep furiously…

exackerly said,

August 23, 2010 @ 12:03 pm

@army1987, "ventiosi" doesn't work very well in Italian, it's too close to "ventosi", which is an actual word.

Theodore said,

August 23, 2010 @ 3:15 pm

More than wondering about whether it's possible to translate this class of nonsense into remote languages, I wonder how often such translations result in a non-nonsense phrase in the target language.

I notice that the Jabberwocky Variations does not contain a Lithuanian Translation. I started that effort for fun some time ago, but never finished. The internal vowel alternations that make Lithuanian past tenses fit right in with the English "verbs" like outgrabe (past of outgribe).

I ended up learning some new vocabulary items when my first choice of an inflected nonsense word turned out to be a real word.

JakeT said,

August 23, 2010 @ 10:44 pm

Oh, man, I love that clip. It's been fundamental in embiggening my vocabulary.

stik said,

August 25, 2010 @ 11:18 am

Genjli Beepboffin

was a murktitious man

with a gelb-rotten, ritten-deep,

skeng-dipple plan.

But his scrug dimple faceliness

and n'affel-wit tan

set wozzels ablazing

for the unwozzel ban.

With nope whistles afterfirth

Beepboffin ran,

till a wozzel cawt Gwenjli,

the repshank thiefman.

A scapley plan hatchel him:

raight grately swum

the Krayk-lake with snakes in

underfirth wozzel wun.

With repshank in bundel

and wozzel by ground,

Gwenjli Beepboffin

made lungflumping sounds.

And afterfirth home,

undelbin Merthyll town,

the repshank were eaten

and washed sweetly down.