Period speech

« previous post | next post »

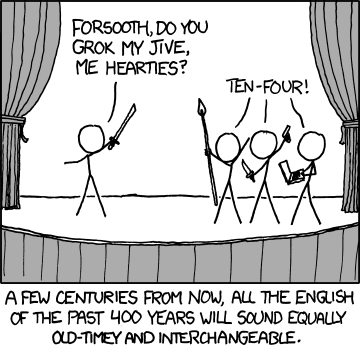

From xkcd a little while ago:

From Terry Gross's interview with David Mitchell ("Mitchell's 'Thousand Autumns' On A Man-Made Island", Fresh Air, 8/5/2010):

MITCHELL: I went wrong twice and had to throw aside about 18 months worth of work at one point. But eventually, by going wrong, I slowly began to work out how I could go right and this historical novel grew out of that.

GROSS: What was one of the mistakes that you made when you went wrong?

MITCHELL: Language, that was the biggest baddest mistake really, Terry. What language are these people speaking? If you try to get it right, if you try to get authentic 18th century speech you end up sounding like "Black Adder," you end up sounding like pastiche. If, on the other hand, you don't, you don't convince your reader that the language, you know, smells authentic, then – bubble of fiction is popped because the reader's thinking, hang on, this sounds like speech that could have been from a sitcom I saw last week.

So you have to sort of create what I came to think of as a bygone-ese kind of dialect, which is not in fact completely plausible. It doesn't really work if you have characters using the word harken, for example. But which still smells and has the right texture of 18th century speech. And it's tough to do that. It's tough to work out exactly how to do it.

GROSS: And then you have to be consistent once you've figured it out.

Mr. MITCHELL: Oh, you have to be consistent. And then, of course, you have to avoid the trap where my rather large cast in this book – I think someone worked out there's about 150 speaking parts in it – they mustn't all sound the same because that also pricks the bubble of fiction. That also makes the reader think, well, why are all these people speaking the same voice? That doesn't happen in life. So you have to work out bygone-ese but then subdivide it amongst the Dutch, the Japanese, the British.

GROSS: It sounds like you really made life hard for yourself.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Patrick O'Brian worked hard (and I think successfully) at this kind of historical recreation (see here, here, here, here , here, here, here, here for some exemplification and discussion).

It's easy to point to other series of historical novels, including some very enjoyable ones, where this problem is not handled very well. But since I don't spend my weekends at Re-enactment Festivals, I won't name names.

Jonathan Badger said,

August 15, 2010 @ 10:05 am

Not the David Mitchell I (and I expect most people) had in mind when first reading the interview. Not that it was immediately obvious, as the other David Mitchell also has a strong interest in both history and language, as evidenced by the number of sketches with a historical or linguistic flavor that he's done.

[(myl) The woods are full of 'em, as my first Latin teacher used to say when we failed to recognize an ethical dative or a genitive of memory.]

Twitter Trackbacks for Language Log » Period speech [upenn.edu] on Topsy.com said,

August 15, 2010 @ 10:11 am

[…] Language Log » Period speech languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=2554 – view page – cached August 15, 2010 @ 9:37 am · Filed by Mark Liberman under Language and culture, Linguistic history Tweets about this link […]

Jonathan Lundell said,

August 15, 2010 @ 11:48 am

Something similar but geographic happens for regional accents, especially noticeable in trans-Atlantic English TV productions.

Actor Michael Kitchen narrates some of author Michael Dibdin's Aurelio Zen novels (detective Zen works for the Italian police). I'm reliably informed that Kitchen's Italian accents (the books and reading are in English) are grossly inauthentic, but they sound entirely convincing to me, who knows no better. The key, I think, is that Kitchen confidently sells the accent. I suppose that something like that obtains on the page: just make me believe it.

Nick A said,

August 15, 2010 @ 11:48 am

Cf. Ursula le Guin's essay 'From Elfland to Pougkeepsie' on style in fantasy novels, where she illustrates the bubble-popping effect by producing a convincing passage for a modern political novel by changing four words in a passage of fantasy dialogue.

Nick A said,

August 15, 2010 @ 11:50 am

Oops: 'Poughkeepsie', I meant.

Vasha said,

August 15, 2010 @ 11:57 am

After reading some of Patrick O'Brian's stories set in the present day, I'm inclined to think that he falls into the "just make me believe it" school of period speech rather than accuracy. The modern stories have quite similar dialogue, i.e. something you'll never hear: they're speaking "O'Brianese", but it's a savory enough dialect that we're willing to believe that it's the sound of the early 19th century.

Jongseong Park said,

August 15, 2010 @ 12:44 pm

I was recently consulted on the transcription of proper names into the Korean alphabet for an ongoing translation of English author Bernard Cornwell's Warlord Trilogy. This is a work of historical fiction based on Arthurian myth and has a jumble of names from Welsh, Latin, French, and English sources with orthographies reflecting disparate time periods. The linguistic inconsistencies and sometimes impossibilities are mind-boggling at times.

For instance, Guinevere's sister is named Gwenhwyvach (it would be Gwenhwyfach in Modern Welsh orthography). The author states that he wanted to keep the familiar form Guinevere instead of Gwenhwyvar (Gwenhwyfar), but he could have harmonized the sister's name as Guinevak. Ceinwyn, a Welsh name which would have been exclusively male at this time period, is used for a female character. Cadalcholg is given as an Irish name for Excalibur instead of the correct Caladcholg or Caladbolg. Curiosities such as Britons with Middle French names are numerous.

Of course, most readers would simply see a whir of exotic, authentic-looking names. It was only by doing research on these names that I discovered the many inaccuracies. I suspect even the names used in most works of historical fiction will fail to live up to scrutiny in general.

Jean-Pierre Metereau said,

August 15, 2010 @ 12:56 pm

Walter Scott in "Ivanhoe" and other novels invented a sort of faux medieval English that moderns can understand. This "language" has a name, and I came across it once, but I've forgotten it. If anyone knows what that name is (it originated with a 20th century scholar, not with Scott) I'd love to know what it is.

And yes, I've used the Google, but got no joy.

Jongseong Park said,

August 15, 2010 @ 2:14 pm

I found out during the aforementioned research that Ivanhoe is responsible for introducing the name Cedric, a metathesized version of the original Cerdic, which itself is probably the Saxon adaptation of an early British name corresponding to Modern Welsh Caradog.

john riemann soong said,

August 15, 2010 @ 2:16 pm

actually the timespan of the illusion is kind of interesting.

mutual intelligibility seems to be "reverse-logarithmic" — that is, you hardly notice if two different dialects are 10% different (by say some arbitrary algorithm of lexical similarity); the difference may be akin to the differences between Canadian and Continental French, but at 15% the difference becomes annoying; at 25% difference you need footnotes but 35% difference you need a complete translation. (the numbers are rather arbitrary but that's what I feel like it is)

m said,

August 15, 2010 @ 3:05 pm

One name for Scott's English is "tushery" because the characters always said "tush." First google hit defines it as "the use of affectedly archaic language in novels, etc.

[coined by Robert Louis Stevenson" — Scott DID have his characters say "tush" a lot.

Debbie said,

August 15, 2010 @ 3:29 pm

How about Emma Thompson's screenplay for Sense and Sensability? And her acceptance speech? Just make me believe if the purpose is entertainment.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q5prYhXQtCk&feature=related

John Cowan said,

August 15, 2010 @ 5:16 pm

Nick A.: The work Le Guin's referring to is the original edition of Katherine Kurtz's Deryni Rising. This book and its two immediate sequels have been revised by the author, but I don't know if this passage remains intact.

Jean-Pierre: "Wardour Street English" is the term I know, referring to a London district where fake antiques were sold.

Vasha said,

August 15, 2010 @ 6:01 pm

I actually love some of the best examples of Victorian faux-medievalism, such as William Morris or Howard Pyle's Robin Hood. Why not go to Wardour Street shopping for beauty instead of authenticity?

Ran Ari-Gur said,

August 15, 2010 @ 7:24 pm

I wonder if that xkcd is right. Suppose we take "a few centuries" to be, say, 250 years. I mean, I don't think think that most English-speakers today would consider all English between 1360 and 1760 — pre-Chaucer to post-Swift — to "sound equally old-timey and interchangeable", would they? (I suppose that English changed more, in many ways, between 1360 and 1760 than between 1610 and 2010, meaning that the comparison isn't perfect, but still.)

Will Steed said,

August 15, 2010 @ 8:50 pm

Australian fantasy author Traci Harding used modern idiom with thou pronouns and conjugations to represent colloquial speech in Old Welsh. It's quite the clever idea, even if it's a little jarring at first ("I will kick thy royal butt", for example). On the other hand, her editor didn't pick up the inconsistently conjugated verbs and case marking that went with it ("Thee must go", "Thou doth…", etc.). With matching reference and conjugation, it would have made a much more entertaining read.

Peter said,

August 15, 2010 @ 9:48 pm

@Jonathan Lundell,

Being an Australian it's very noticable when Australian characters in American TV shows don't sound anything like any Australian I've ever heard.

Of course, the worst one I've come across mispronounced the name of the town he was supposedly from. I bet 99% or more of the viewers didn't even know it was wrong, but it amused me.

Joyce Melton said,

August 16, 2010 @ 4:59 am

Both Al Capp and Walt Kelly invented their own southern dialects for their successful comic strips, Li'l Abner and Pogo. They're pretty funny whether you're a southerner or not.

And in the Beverly Hillbillies, none of the four main actors had an authentic mid-South "hillbilly" accent. Buddy Ebsen was from Ohio, Irene Ryan from West Texas, Donna Douglas from Louisiana and Max Baer, Jr. from California. Max and Buddy were closest though, the "Ahiya" Valley accent is sort of near-South if not mid-South and Max's famous father was from the Ozarks, providing a live model.

As an authentic hillbilly (I was born on Crowley's Ridge), Max, Buddy and Irene were convincing and Donna Douglas sounded like someone doing the accent phonetically. All Irene had to do was avoid saying "y'all" in that peculiarly Texan way which she did by saying "y'uns" instead. :)

phrontisterion said,

August 16, 2010 @ 5:39 am

Watching the Beverley Hillbillies reruns a few years ago, I was struck by the scriptwriters' attention to linguistic detail. As Joyce Melton said, the actors were all non-Hillbillies but they all regularly for example said 'hep' for 'help'. Is this a recognised dialect marker in the US?

[links] Link salad goes creeping now through the night and the poison gas | jlake.com said,

August 16, 2010 @ 8:00 am

[…] Period speech — Language Log on a perennial problem for authors. […]

Nicholas Ostler said,

August 16, 2010 @ 9:18 am

I thought the last word on all this had been said at http://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/Ptitlebb330lv9nf12 on the "The Queen's Latin", where much evidence is offered that simple use of RP is good enough to satisfy most English-speaking audiences (well, US ones) that "we are in the past, here".

stephen said,

August 16, 2010 @ 2:23 pm

Regarding period speech–what if I'm writing a story set in ancient times, or even prehistoric times? Shall some characters sound like they're from the American midwest, some sound like Victorian Britons, some sound like geishas and some sound like pirates? (I'd avoid using words like "aroint". But shall I use "thee" and "thou"?)

Regarding accents–

I know somebody who was born in Virginia, but who sounds *exactly* like Jonathan Winters, who was born in Bellbrook, Ohio (according to Wikipedia.)

I don't know if that's significant or interesting, but the accents are so similar.

Rich Little was on a documentary doing Richard Nixon; they compared the voiceprints, and Rick Little's voiceprint was completely different from Nixon's. Why do they sound the same if the voiceprints are different?

G.W.Bush Jr. was born in New England; I wonder how much his accent has changed–I can't tell what region his accent suggests. I wonder if he had a coach to help change his accent.

I was told John Kennedy's accent is unique to the Kennedy family. Nobody else in New England sounds like that? Is that true?

Jim said,

August 16, 2010 @ 2:51 pm

"As Joyce Melton said, the actors were all non-Hillbillies but they all regularly for example said 'hep' for 'help'. Is this a recognised dialect marker in the US?"

Yes, and it's highly marked socially. It's the equivalent ot what dropping the "h' used to be.

Richard said,

August 16, 2010 @ 2:56 pm

Ran:

Huge changes in the English language between 1360 and 1760. However, if an author mixed & matched words, phrases, and grammar from Shakespeare and Austen (and the 250 years in between), how many modern English-speakers would notice the incongruity?

Ran Ari-Gur said,

August 16, 2010 @ 6:56 pm

@Richard: I suppose it depends. I would certainly notice anachronistic Shakespeareanisms in a play set during Austen's time, as I think would most people who've read any of her novels. But in a play set in Shakespeare's time, I'd probably accept anachronistic Austenisms (modernisms, really), much as I'd accept a work that's set in France but all of whose dialog is in English. (But anachronistic Austen-era slang/jargon, like some of xkcd's examples, would probably stick out, not so much as anachronistic as as unintelligible.)

Jonathan Lundell said,

August 16, 2010 @ 7:22 pm

@Peter, I can distinguish several Australian accents (not identify, but recognize as different), but I have no way to anchor them to a location or milieu. I worked for several years with a Kiwi who lived much of his life in Sydney, and that experience has no doubt led to terminal confusion on my part.

I'm listening to a recording of Reginald Hill's Bones & Silence, and am hearing a wondrous variety of Yorkshire accents. The reader is Brian Glover, so I assume they're more or less authentic.

OTOH, I can usually distinguish between Manitoba, Minnesota and Wisconsin accents, having lived in that area long enough to have a lot of referents.

[Last & least: obligatory mention, in this context, of Riddley Walker.]

Amy Stoller said,

August 16, 2010 @ 7:45 pm

@phrontisterion: The pronunciation of "help" as (roughly) "hep" is an accent feature that can – and does – occur in American English in various parts of the American South. But you can expect to hear it speakers from these various regions regardless of whether they are speaking local dialect or "standard" AmE.

@Stephen: I suspect that what we hear in Rich Little is the highlighting of certain features of Nixon's idiolect, including intonation. It isn't necessary to reproduce every authentic detail in order to create the impression of authenticity. Think of the difference between a photograph and a caricature. In both cases the subject will be recognizeable – and in some cases, the caricature will be held to have captured more of the subject's essence than the photograph.

As for historical novels, it is a very tricky job. I am sometimes jarred by anachronisms that I suspect most readers wouldn't notice; and I do notice when English novels get fundamental aspects of American English wrong. I also notice many instances the other way round, but since I am American, not English, I am likelier to miss some of those. (I'm fluent in BrE, but I'll never be a native speaker.)

Peter said,

August 16, 2010 @ 8:21 pm

@Jonathan, I'm not saying there aren't different Australian accents (although they don't seem to be as different as regional accents in America or Britain), I'm saying the accents don't match what's usually used in American TV (and movies for that matter). I'm often watching for half an hour or more wondering "is that character supposed to be Australian or British?"

And for the record, I've been to all mainland Australian states and lived on both sides of the country.

Mabon said,

August 16, 2010 @ 10:02 pm

Re: Stephen: I was told John Kennedy's accent is unique to the Kennedy family. Nobody else in New England sounds like that? Is that true?

Yes, that seems to be true. I suppose there may be a person around who was raised in similar circles whose accent approximates the Kennedys' — but nobody comes to mind.

Can anyone come up with an example?

Jerry Friedman said,

August 16, 2010 @ 11:41 pm

@Jongseong Park: I don't read much historical fiction. My record anachronism in names is in The Physician (1986), by Noah Gordon, which begins in England in 1020. The hero's name is Rob J. Cole.

Jonathan Lundell said,

August 17, 2010 @ 1:41 am

@Peter, I'm not disputing your point, either one of them. And I've wondered the same thing: Australian or British? I'm halfway convinced that there's at least a British accent that's in some sense "closest" to an Australian. But maybe it's just bogus….

Rodger C said,

August 17, 2010 @ 8:42 am

@Jerry Friedman: I found this so amusing that I went and looked up Noah Gordon. Apparently he wrote a trilogy about physicians in three different historical periods, each descended from the previous one and all named Rob J. Cole. So apparently Gordon made a conscious decision to use this as a linking device and let name plausibility go hang.

Jongseong Park said,

August 17, 2010 @ 10:20 am

@Rodger C: Although at least according to Wikipedia, the success of The Physician led to the extension into a trilogy, so he didn't necessarily have the name as a linking device in mind when he came up with Rob J. Cole as the name of an English boy during the rule of Canute.

Rodger C said,

August 17, 2010 @ 11:11 am

@Jongseong Park: How strange. Even Robert by itself is an implausible name for an Englishman before 1066.

Jongseong Park said,

August 17, 2010 @ 12:08 pm

@Rodger C: The Pase Index of Persons records a number of individuals named Robert in Anglo-Saxon England, including a brother of Ely Abbey (Cambridgeshire) c. 970-1030, with the note, 'Perhaps a Frank or a Norman'. So I guess it's not completely outside the realm of possibility…

What I'm struck by is that Rob J. Cole is the incongruous middle initial. How many London boys have surnames at this time period, let alone a middle name?

Rodger C said,

August 17, 2010 @ 6:18 pm

Harold J. Godwinson?

Jerry Friedman said,

August 18, 2010 @ 10:29 pm

@Jongseong Park: If he was a Frank or a Norman, how could he be a Robert? :-)

Yes, that middle initial is the master touch, and to emphasize it, the narration sometimes refers to him as Rob J.

By the way, the Wikiparticle says The Physician sold much better in translation, especially in Spain and Germany, than in the original. It adds without a reference that in "1999, Madrid Book Fair attendees called The Physician, 'one of the ten most beloved books of all time'."

I thought it was engaging and didn't take it to be a history lesson.

John Crowley said,

August 20, 2010 @ 9:08 am

T.H. White in The Once and Future King (the Arthur story) had a wonderful solution to the language problem. Though his Normans/Englishman all speak like Englishmen of White's time (1920-50), when a knight must say something deeply felt, or make a vow, or challenge another, he uses what White calls the "high language," i.e. Malory's English, intact.

Terry Collmann said,

August 22, 2010 @ 7:22 pm

Jonathan Lundell: "I'm halfway convinced that there's at least a British accent that's in some sense 'closest' to an Australian". As I believe I've said here before, Londoners report that in America they're regularly mistaken for Australians.

Mithras The Prophet said,

August 26, 2010 @ 7:28 am

@john riemann soong: Fascinating. I suppose by "reverse logarithmic" you might mean "exponential," eh? And your point strikes me as almost certainly correct.