Simplified vs. complicated in New York state

« previous post | next post »

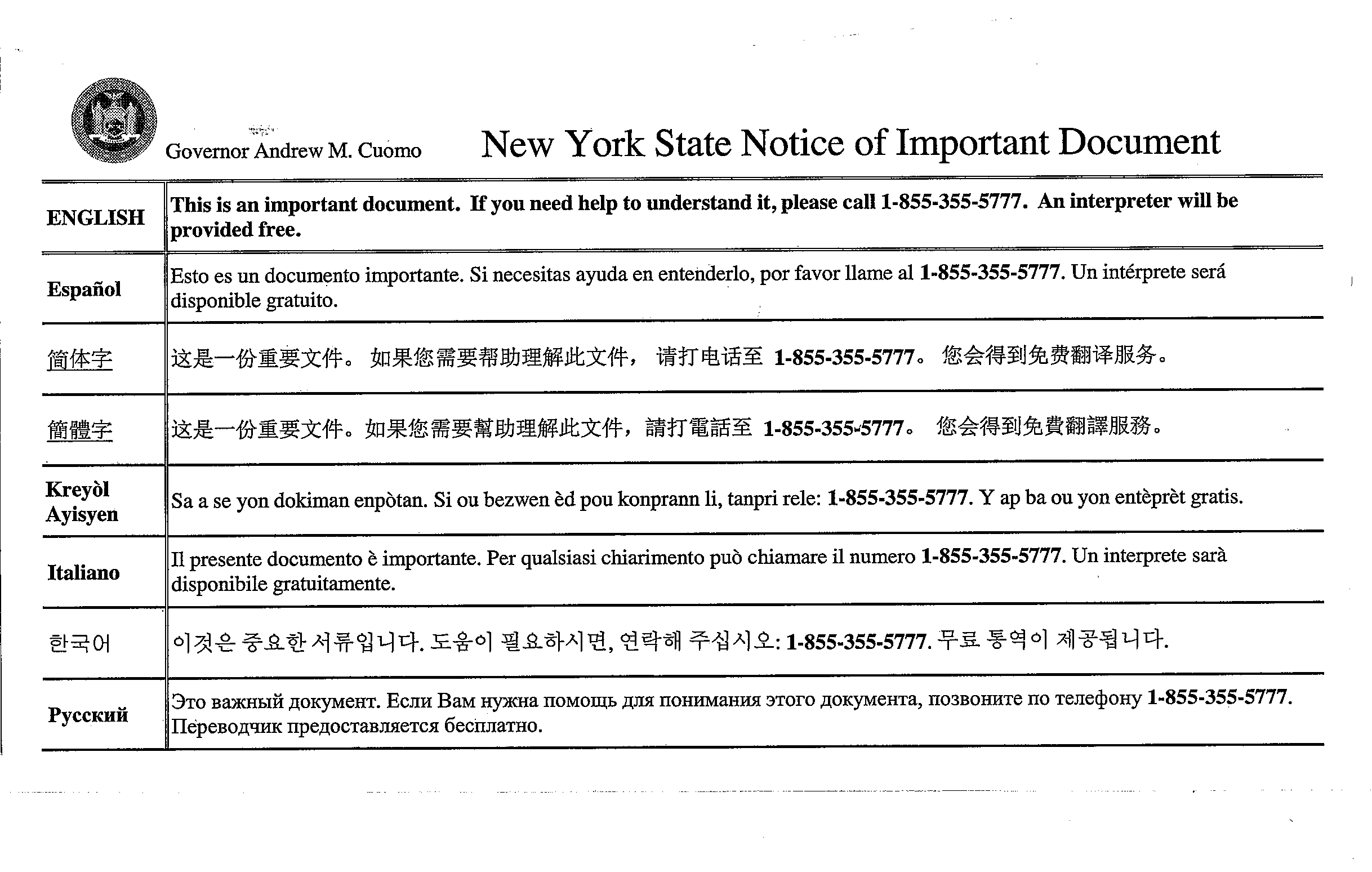

Cullen Schaffer sent me the following scan (click to embiggen):

It was accompanied by this note:

A couple of years back I sent you the attached scan of the back of an envelope sent out by the New York State health insurance exchange, drawing your attention to the headings for the two Chinese entries in the list of languages. I wonder if you got a chance to look at it. I still get exactly the same envelope in the mail from them every month.

I am a little bit embarrassed because, upon looking in my back e-mail, I see that I did indeed receive this scan on 9/6/14, and that, on the very same day I replied, "I'll turn to it before long". Ahem! I usually don't neglect things this way, but sometimes I do get snowed under.

Better late than never!

Now that I contemplate the multilingual notice on the back of the envelope, I think I understand why I was stymied the first time and didn't feel like I had anything useful to say. Namely:

1. If they only had room for eight languages, I can't understand why they'd make two of them the same language, viz., bastardized Mandarin, and one of them Haitian Creole.

2. The bànwén bànbái 半文半白 ("semiliterary-semivernacular" — that's what I was referring to as "bastardized" in the previous item) quality of the Chinese in a notice that is intended for the general Chinese-speaking population, which includes cooks, waiters, mechanics, carpenters, garment workers, and so forth, put me off a bit.

Still harboring the same reservations and doubts, I asked several colleagues and students their opinion about the two Chinese versions. The broad variety of their views underscores my own uncertainty about the wisdom of including these two lines of Chinese on the back of the envelope that goes out to so many people in the state of New York every month. Here are the questions I asked:

1. Do you think it's necessary to have both the simplified and the traditional versions of the characters in an official announcement from the New York state government?

2. What do you think of the language of the notice? It seems like a somewhat odd mixture of báihuà 白话 ("vernacular [Mandarin]") and wényán 文言 ("literary [Sinitic]").

Here are the replies I received:

1. A mainland graduate student in Chinese history:

I think I am not qualified to answer the first question since I can read both simplified and traditional Chinese. As for the second one, it is not odd to me. I think it is written by a person who has learned Chinese very well.

2. A mainlander who received their Ph.D. in Chinese literature in America and has been teaching Mandarin here for more than twenty years:

I read the notice and did find the Chinese translation awkward. Classical Chinese is very much alive in the written or formal vernacular language, but this translation is not a good representation of it. Unfortunately I noticed that many people even expect this type of awkward wording in translation.

To answer your other question, personally I don't think it's necessary to use both simplified and traditional characters, especially for this notice, since there are few characters that are different. But for people who are only familiar with one form of the characters, the need to provide both might be there.

3. An M.A. candidate in Chinese Studies who is from the mainland:

In terms of the grammar per se, it's more like a word for word translation from English, intelligible but not 100% idiomatic for sure. Wenyan style is considered formal and suitable for governmental documents in mainland China today, to say nothing of Taiwan, whose wording and phrasing seem more ancient style (or, let's say traditional “正统”). The choice of language is very well a representation of how the user images itself.

4. An instructor of Mandarin from Taiwan who has been teaching in the United States for more than twenty years:

Yes, I think it is necessary to have both simplified and traditional characters as most of the old immigrants from China or any immigrants from Taiwan still read traditional characters and there are plenty of them in the New York State. As for the language, it is quite baihua to me. I would say it's a mixture of colloquial and formal wording. For example, "lijie" and "ci" sound a bit too formal here, though the other words sound ok. Also, the sentences sound a bit odd because of the way they were translated. The grammar sounds more English than Chinese to me.

Regarding the quality of the language, I realize that some people do write like this (mix vernacular and literary) when they want to seem learned or official, but it's a practice that pure Mandarin stylists from Hu Shih up through the present time have decried.

For the record, here are the two versions of the Chinese:

Jiǎntǐ zì || Zhè shì yī fèn zhòngyào wénjiàn. Rúguǒ nín xūyào bāngzhù lǐjiě cǐ wénjiàn, qǐng dǎ diànhuà zhì 1-855-355-5777. Nín huì dédào miǎnfèi fānyì fúwù.

简体字 || 这是一份重要文件。如 果您需要帮助理解此文件,请打电话至1-855-355-5777。您会得到免费翻译服务。

簡體字 || 這是一份重要文件。如果您需要幫助理解此文件,請打電話至1-855-355-5777。您會 得到免費翻譯服務。

It's strange that, in the years since this envelope has been circulating, no one (including all of my informants) has corrected a flagrant error right at the beginning of the Chinese notice. In the second version, jiǎntǐ zì 簡體字 ("simplified characters") should be fántǐ zì 繁體字, but therein lies the rub. People are reluctant to call the full / original / traditional forms of the Chinese characters fántǐ zì 繁體字 because that means "complex / complicated characters", and can even connote "cumbersome" or "difficult". On the other hand, I don't know of any other common way to refer to the full / original / traditional forms of the characters in Chinese than as fántǐ zì 繁體字.

[Thanks to Maiheng Dietrich, Melvin Lee, Yixue Yang, and Fangyi Cheng]

Tom said,

March 18, 2016 @ 9:36 am

Also, zhè ("this") is written in both versions as 这, the simplified form—another mistake in the complex version!

J. W. Brewer said,

March 18, 2016 @ 9:41 am

Haitian Kreyol fwiw is these days one of the more significant minority languages in New York, and is frequently seen in governmental contexts when the "menu" of non-English options is larger than three or four. Actually probably once you get past English/Spanish/"Chinese" the order in which additional minority-options appear as the list gets longer is not all that stable/predictable, and depends either on context (some sorts of governmental services will have different patterns of language use in the relevant user population than others) or semi-arbitrary whim. For example, the website for the New York state Department of Taxation and Finance gives six non-English options for LEP taxpayers: "Chinese," Italian, Korean, Kreyol, Russian, and Spanish. I am not competent to identify characters as traditional vs. PRC unless two pieces of running text are shown side-by-side, but the tax authorities only offer one version of "Chinese," which can be seen here: https://www.tax.ny.gov/language/chinese/.

Victor Mair said,

March 18, 2016 @ 9:46 am

@J. W. Brewer

That page from the tax authorities is all in traditional characters.

Lai Ka Yau said,

March 18, 2016 @ 10:38 am

To be honest, I don't think it's basterdised because it's semi-vernacular, semi-classical. On the contrary, I find it too vernacular to be used in an official text – I think 此乃 would work much better than 這是一份, for instance…

But the main problem with the translation, as I see it, is the iffy syntax: 如果你需要幫助理解此文件。The 幫助 has no subject or object…

Bruce Rusk said,

March 18, 2016 @ 10:44 am

In Taiwan, fantizi 繁體字 are called zhengtizi 正體字 ("standard-form characters" or "orthodox characters") in official contexts. For example, at one time the National Palace Museum in Taibei had both traditional and simplified versions of its homepage. The simplified version has disappeared (the result, no doubt, of a political decision), but the language menu still labels it zhengti Zhongwen 正體中文 ("Chinese in orthodox characters").

Of course, this appellation could be offensive to users of simplified characters, since it bears the implication that the latter are "unorthodox" or "incorrect."

Cullen Schaffer said,

March 18, 2016 @ 4:20 pm

Funny, I *only* sent this in because of the "flagrant error" mentioned at the very bottom of the response. I like that the two headings for Mandarin are "Simplified characters" in simplified characters and then "Simplified characters" again in traditional characters.

Chau said,

March 18, 2016 @ 5:27 pm

Echoing Bruce Rusk,

here is a page from Wikipedia on 太陽花學運 the Sunflower Movement – today is the second anniversary of that eventful day in Taiwan's political history. Look at the task bar above the title of the entry, it says 台灣正體 Taiwan orthography.

https://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%A4%AA%E9%99%BD%E8%8A%B1%E5%AD%B8%E9%81%8B

AntC said,

March 18, 2016 @ 8:03 pm

@J.W.Brewer, yes when you think what a melting-pot is New York, I'm surprised at the choice of languagess

Russian but not Polish? Spanish and Italian [fair enough], but no northern European languages — German, Yiddish, Dutch (NY was originally New Amsterdam). No African languages? It would demonstrate a more welcoming regime to include Arabic. I'm looking at the spoken languages list here https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_York

Perhaps (trying to be generous) New York State has done a scrupulous analysis of its 'customer base'? And it knows that speakers of those other languages also have enough competence at English?

But a phone number; no website where you could access a translation into a gazillion languages. So you phone the number and start talking Xhosa. Where's that going to get you?

John said,

March 18, 2016 @ 11:12 pm

@Tom

"Also, zhè ("this") is written in both versions as 这, the simplified form—another mistake in the complex version!"

There are many more errors than just this.

Although putting the name of the language itself isn't strictly necessary, if they were including Serbocroatian, would there just be a heading of "Latin" and "Cyrillic"?

Victor Mair said,

March 19, 2016 @ 7:03 am

From Tom Bartlett:

I don’t really consider this to contain “literary” Chinese features, but I suppose that judgment depends on what standard one holds for the distinction between colloquial and literary. I’d say it’s a mix of colloquial and written styles that are common in modern 白話 Chinese. But this is an area of concern that I have not thought much about, so my standards may not be very refined.

I do agree that the syntax of the second clause 如果您需要幫助理解此文件 is very awkward, and reads like what it is, an unnaturally parallel (and unnecessarily full) direct translation from the original English.

English is typically more explicit in details than Chinese. So this entire clause could be omitted, since its meaning is clearly implied by the following two clauses, which could be rewritten quite adequately as 免費翻譯服務, 請撥 1-855-355-5777. But maybe 撥 is too “literary” for some tastes. In that case, maybe use 打 instead of 撥 (?).

Victor Mair said,

March 19, 2016 @ 8:02 am

From JSR:

This old article cited a dispute in NY schools between Chinese parents as to which characters to teach:

Ni Ching-ching. “Which Character to Teach? School’s Class in Chinese Splits.” Newsday. (Nassau and Suffolk editions). May 2, 1999.

Sorry I have lost the link to the original article.

Victor Mair said,

March 19, 2016 @ 8:29 am

Both in his original message and in his follow-up, Cullen Schaffer mentioned "the headings for the two Chinese entries", but there were so many other problems with the biscriptal Chinese notice that I didn't focus on the headings until I was almost done writing the post.

Grover Jones said,

March 19, 2016 @ 10:18 am

The English doesn't even sound right. Most in my background would say "help understanding it" not "help to understand it." And the last sentence sounds much naturaler as "provided for free."

Levantine said,

March 19, 2016 @ 10:44 am

Grover Jones, the English sounds fine to me. "Free" is traditionally used without a preceding "for", and I believe this usage is still widespread (and perhaps slightly more formal than "for free").

Out of interest, was your use of "naturaler" jocular?

sugarloaf said,

March 19, 2016 @ 11:06 am

Whatever about the Chinese language(s), even the Spanish is wrong, I think. necesitas > llame.

Generally, why are translations so bad? Everywhere around the world? Most languages are fully known and described, and there are plenty of proficient speakers. Just laziness, I suppose.

Catanea said,

March 19, 2016 @ 4:13 pm

Often parsimony rather than laziness, I suspect.

David said,

March 19, 2016 @ 5:41 pm

Sugarloaf, that it is a small mistake. The last phrase in the spanish translation is completely wrong. So probably the remaining translations are also full of mistakes.

David Morris said,

March 20, 2016 @ 5:33 am

I am always intrigued when the name of the language (in the left hand column here) is given *in that language* and *in that script* – eg 한국어 rather than 'Korean'. This is not helpful for the vast majority of people. The people who can read the main information (in the right hand column here) already, don't need to be told the name of that language, while English-only-speaking helpers, trying to find information for a non-English speaker, can't find that information.

I can't check, but I think that on similar notices in Australia, the languages are given as '한국어 – Korean'.

/ said,

March 20, 2016 @ 12:48 pm

@sugarloaf

"Generally, why are translations so bad? Everywhere around the world?"

Laziness, parsimony, or perhaps just ignorance.

Problem is, How do you know what you don't know? Let's say a Chinese shopkeeper in China wants a sign translated. He asks around and someone says: "Chan is very good in English! He's translated letters for me into English! He lived in America for three years! He teaches English in middle school!" Thing is, Chan can have all those qualifications but still has poor English. Chan is then asked to translate the sign and none of the Chinese people around the shopkeeper realizes it is not in good English. ….A personal experience: My father (Chinese) had a group of close Chinese buddies (all middle-age), among them one Sherman. Sherman was greatly admired because they all thought his English was exceptionally good. They'd say: "Sherman studied in America. His English is so-o-o good." I grew up hearing how great Sherman's English was. Years later, my mom showed me, admiringly, a letter Sherman had written in English. I read it. It was in English, yes, but in poor, ungrammatical, English. And all those years Sherman was to me this glamorous figure, all because he had good English.

julie lee said,

March 20, 2016 @ 12:49 pm

oop, that "/" was me. I forgot to type my name.

Levantine said,

March 20, 2016 @ 4:41 pm

sugarloaf, it could also be the result of asking under-qualified heritage speakers (perhaps those employed in the relevant offices) to do the work. I suppose this is an unlikely explanation in the case of Spanish in New York, where there are many truly bilingual speakers, but I've seen translations into Turkish here in London that have clearly been authored by heritage speakers who don't have a full command of the language.

Rodger C said,

March 22, 2016 @ 6:54 am

I suppose this is an unlikely explanation in the case of Spanish in New York, where there are many truly bilingual speakers

Many of whom are quite fluent in a Spanish full of Anglicisms, which would explain clangers like "disponible gratuito," referenced above.

Alyssa said,

March 23, 2016 @ 10:39 am

"For free" may be new, but it's become common enough that personally "provided free" strikes me as ungrammatical as well. Something can be free, or it can be provided for free, or provided free of charge, but not provided free. "I got it free" sounds somewhat better, but I still wouldn't say it.

Levantine said,

March 23, 2016 @ 5:21 pm

Alyssa, I'm surprised you say it sounds ungrammatical to you rather than just less natural. To me, the difference is akin to that between "On Monday" and plain "Monday" — neither sounds wrong, even I prefer one form over the other