Physiological politics

« previous post | next post »

Carl Zimmer, among other readers, has pointed me to the latest outbreak of bio-political punditry. This time it isn't David Brooks, but rather Nicholas Kristof, "Our Politics May Be All in Our Head", 2/13/2010:

We all know that liberals and conservatives are far apart on health care. But in the way their brains work? Even in automatic reflexes, like blinking? Or the way their glands secrete moisture?

That’s the suggestion of some recent research. It hints that the roots of political judgments may lie partly in fundamental personality types and even in the hard-wiring of our brains.

Researchers have found, for example, that some humans are particularly alert to threats, particularly primed to feel vulnerable and perceive danger. Those people are more likely to be conservatives.

Kristof's "recent research" link goes to Kevin Smith, Douglas Oxley, Matthew Hibbing, John Alford, and John Hibbing, "The Ick Factor: Disgust Sensitivity as a Predictor of Political Attitudes". The abstract:

Mounting evidence suggests political attitudes connect to broad, dispositional, perhaps biological temperaments. We add to these empirical results by reporting a correlation between certain political attitudes and physiological reactions to disgusting stimuli such as human excrement and worms being eaten. Specifically, we find that individuals whose skin conductance levels increase when viewing disgusting images are more likely to adopt “conservative” positions on homosexuality and perhaps a broader range of “sex and reproduction” issues, a result that serves as a useful illustration of the larger point that political attitudes cannot be separated from generic physiological traits.

This is listed as a "Paper prepared for presentation at the annual meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association", April 2008; but unfortunately, the copy available at the link given is almost impossible to read (because the type is so small, with no method that I could find to enlarge it), and I couldn't find another copy on line. [Update — a helpful reader showed me how to get a .pdf, and so I'll blog about Ickology as time permits.]

However, a similar set of ideas and experiments are presented in a more accessible way in Douglas Oxley, et al., "Political Attitudes Vary with Physiological Traits", Science 321:5896, 9/19/2008:

Although political views have been thought to arise largely from individuals’ experiences, recent research suggests that they may have a biological basis. We present evidence that variations in political attitudes correlate with physiological traits. In a group of 46 adult participants with strong political beliefs, individuals with measurably lower physical sensitivities to sudden noises and threatening visual images were more likely to support foreign aid, liberal immigration policies, pacifism, and gun control, whereas individuals displaying measurably higher physiological reactions to those same stimuli were more likely to favor defense spending, capital punishment, patriotism, and the Iraq War. Thus, the degree to which individuals are physiologically responsive to threat appears to indicate the degree to which they advocate policies that protect the existing social structure from both external (outgroup) and internal (norm-violator) threats.

In other words, the Science paper deals with reactions to sudden noises and theatening visual images, correlated with political attitudes toward level of support for what the authors call "protective policies". The nearly-unreadable conference paper makes an analogous argument about reactions to disgusting images correlated with political attitudes towards "sex and reproduction issues", especially homosexuality. So I'm going to discuss the Science paper — if someone can point me to a readable copy of the "disgust" paper, I'll be happy to apply the same analysis there.

(By the way, you can see from the quoted abstracts that Kristof's account of this work is not very different from what the authors themselves have to say about it. This is not a case of egregious journalistic misunderstanding or over-interpretation.)

In the rest of this post, I'm going to go over some aspects of the analysis in the Science paper, and argue that the explanation offered is at least excessive and possibly wrong. I'm somewhat hampered in doing this by the fact that some relevant aspects of the authors' data are not published, and also by (what I found to be) some ambiguities in the presentation of their data and their models. If as a result I've misunderstand what they did or how they interpreted it, I apologize in advance. I plan to write to the authors and ask for clarification and for a copy of their original data, which would allow me (and others) to make a more full and fair evaluation.

First, who were the subjects?

Subjects were recruited in May of 2007 by the Bureau of Sociological Research at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln (BOSR). BOSR contacted a random sample of residents of Lincoln, Nebraska. This initial telephone call followed an introductory letter and was used to pose a limited number of items to respondents with the intention of obtaining a group of individuals with strong political convictions toward whom intense and more focused investigation would be directed. The following three questions were used to screen potential subjects. Yes or no response categories were given for all three questions.

1. Do you follow politics or political issues closely?

2. Is there a certain political issue or set of political issues you feel strongly about?

3. Have you ever supported a particular political issue or cause?

A total of 1310 people were contacted and 608 of them completed the screening items. Subjects were recruited for this particular project only if they responded “yes” to all three questions. A total of 143 respondents did so and were agreeable in principle to coming to the lab. BOSR was able to schedule (and secure the attendance of) 48 individuals at both sessions (survey and physiological) of this project. Health problems rendered the data from one individual unusable and mechanical problems with a sensor spoiled the data from another, leaving a final total of 46 participants.

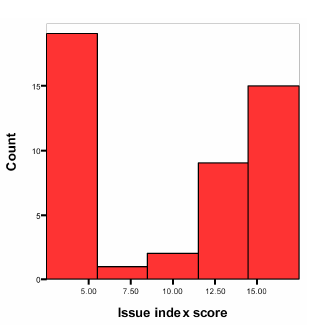

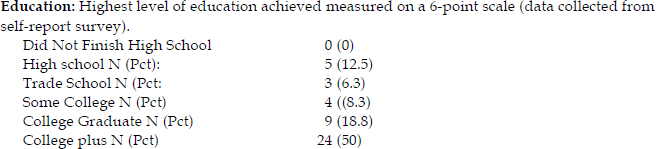

Their sample of 46 subjects included 29 males and 17 females; and the distribution of education levels was also rather skewed:

So how did Oxley et al. measure the subjects' political attitudes about "protective policies"?

The dependent variable … is an additive index of 18 issue items based on a standard Wilson-Patterson battery. For each issue, respondents were asked to “please indicate whether you agree or disagree with the topic listed,” and were given “agree,” “disagree,” and “uncertain” response options. These options were coded as “1” when they indicated support for protective policies (e.g. for agreeing with the death penalty, or for disagreeing with pacifism), “0” when they indicated opposition to protective policies (e.g. for disagreeing with the Patriot act, or agreeing with pornography), and “.5” for an uncertain response.

As I understand it, they made no special efforts to create the bimodal distribution of summed opinion scores that resulted:

They then ran two psychophysiological tests on the same set of subjects. One was a measure of "skin conductance level" (SCL) recorded while

[e]ach participant was shown three separate threatening images (a very large spider on the face of a frightened person, a dazed individual with a bloody face, and an open wound with maggots in it) interspersed among a sequence of 33 images.

"Conductance" here is the inverse of resistance, measured in log μ-Siemens:

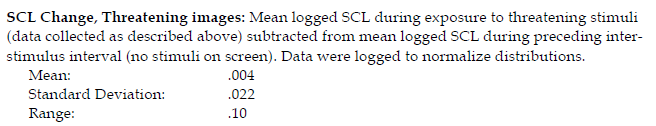

After logging the data to normalize the distribution, we computed the change in the mean level of skin conductance (SCL) from the previous interstimulus interval (10 s) to the stimulus of interest (20 s). This calculation isolates the change in skin conductance induced by the stimulus and reduces the effects of baseline variations across participants.

(Issues of units, normalization, and measurement intervals aside, this is basically the same phenomenona that goes under the older and somewhat more familiar name of "Galvanic Skin Response" or GSR, and is caused by changes in the autonomically-induced activity levels of sweat glands.)

The other physiological measure was the EMG associated with startle blinks, elicited in response to unexpected noise bursts, where "higher blink amplitudes … are indicative of a heightened 'fear state'".

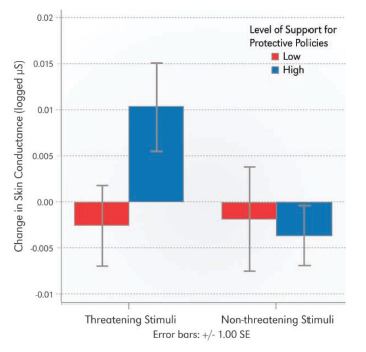

Here's the authors' graphical presentation of the basic result for the SCL measurements. They divided their 43 subjects into those who scored above the median on the "support for protective policies" questionnaire, and those who scored below the median. There was little difference between the groups in response to the non-threatening pictures, but a statistically-significant difference in response to the threatening pictures:

Nicholas Kristof describes the analogous results in the sex-disgust paper this way:

Liberals released only slightly more moisture in reaction to disgusting images than to photos of fruit. But conservatives’ glands went into overdrive.

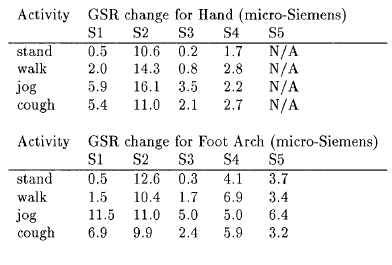

"Overdrive" is a bit of a stretch, I think — for comparison, here's a table from Rosalind Picard and Jennifer Healey, "Affective Wearables", ISWC97, showing SCL changes for five subjects as a result of some simple activities such as standing up or coughing:

The difference in means between Oxley et al.'s "high" and "low" protective-policies groups is about .0125 log μS. Assuming that they used natural logs, this difference seems to be about two orders of magnitude less than the (unlogged) amounts that Picard and Healey measured as the effect of coughing — log(2.4) = 0.88; log(9.9) = 2.29. (This seems like such a preposterous difference that I wonder whether I've got something seriously wrong here — but in any case, I hereby register some skepticism about the "going into overdrive" description…)

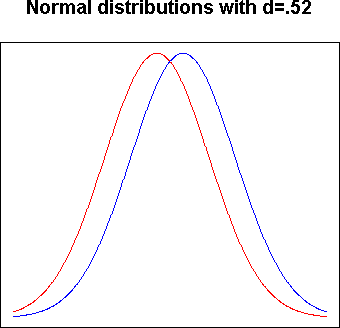

Without making any cross-study assumptions, we can evaluate the effect size in Oxley et al.'s results. From the graph reproduced above, you can see that the difference between the mean (SCL response to threatening pictures) of the "high" and "low" protective-policies groups is about .0125 log μS, with a standard error of about .005 log μS. Given that there were 23 subjects in each category, this translates to a standard deviation of about .005*sqrt(23) ≅ .024 log μS, so that the effect size is about d = .0125/.024 ≅ 0.52.

Though statistically significant, this is only a moderate-sized effect — the associated overlap between the two distributions can be represented graphically this way (assuming normal distributions with equal variances):

We can quantify this difference in intuitive terms by calculating how often a randomly-selected person from the "high support for protective policies" group would have a greater average skin-conductance change, on viewing threatening pictures, than a randomly-selected person from the "low support for protective policies" group would: about 64% of the time.

We can also compare another effect from the same study, namely amount of education. This factor is presumably a matter of "individuals’ experiences" rather than biology — but contrary to what (Kristof's description of) this line of research might lead to you to think, its predictive effect in this experiments was as large as or larger than the effect of the "biological" variables.

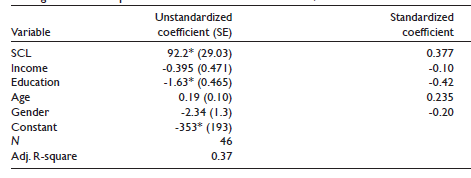

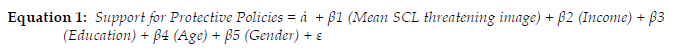

As a result of fitting this regression equation

they derived the following coefficients:

The coefficient of -1.63 for the six-level Education scale means that someone in the "College-Plus" categories was predicted to be 5*1.63 = 8.15 (out of 18) points lower on the "protective policies" scale than someone with a high school education (other things in the regression being equal).

What about the magnitude of the skin-conductance effect? Well, the coefficient is 92.2, which means that the more a subject's SCL reacted to threatening images, the higher their "protective policies" attitude scale was. But recall that the average SCL measurement for the high-protective group was about 0.01, and the average SCL measurement for the low-protective group was around -0.0025 (these measures are log μ-Siemens, so a negative value just means that the conductance measurement was below 1). So the predicted average effect is around 0.01*92.2= 0.922 for the high-protective group, and -0.0025*92.2 = -0.2305 for the "low-protective" group, or an overall mean difference of about 1.15 (out of 18) between the groups attributable to the skin-conductance differences.

In the Supplementary Online Material, we learn the the overall standard deviation of their SCL data was 0.022 log μ-Siemens. So to equal the predicted effect of 8.15 political-attitude points between high-school and college-plus, we'd need an SCR difference of 8.15/(92.2*0.022) = 4.02 standard deviations.

We can draw a similar conclusion by comparing the standardized regression coefficients of 0.377 for SCL and -0.42 for education.

So the SCL "effect size" was modest, not only in the sense that the difference in means between two politically-defined groups was only about half of the within-group standard deviation, but also in the sense that it appears to have somewhat less predictive leverage than educational level does.

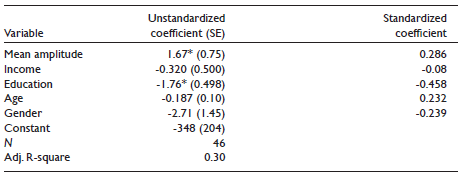

The same comparisons for eye-blink amplitudes lead to similar conclusions. The easiest way to see this is by comparing the standardized regression coefficients for Mean (eye-blink) amplitudes (0.286) and Education (-0.458):

For this model, the predicted effect of the span from highschool to college-plus is 5*-1.76 = -8.8 political-attitude units, and (since the SOM gives the standard deviation of eye-blink amplitude as 0.93) we'd need 8.8/(0.93*1.67) = 5.7 standard deviations of change in eye-blink amplitude to have the same effect as the educational span.

All of this suggests that the "biological" factors of SCL and eye-blink amplitude are somewhat less potent, in this experiment, than the "social" factor of educational level. But it seems to me that in this case, the "biological" factors might turn out to be partly "social" factors after all.

Why? Well, it's likely that political opinion in Lincoln divides to some extent along town-gown lines. It's also plausible that town-gown uneasiness is not unknown in Lincoln, and that a non-academic with conservative opinions, coming into a University laboratory to get wired up with electrodes for a study of political opinions, might have a somewhat higher overall anxiety level than university faculty, students or staff would. This could be true independent of educational level — my own experience is that non-academic lawyers and doctors, for example, often seem a bit uneasy around academics. (And vice versa, but in this case it's the academics who are wielding the electrodes.)

Furthermore, people who are more on edge, in an unfamiliar environment that they perceive as potentially hostile or at least potentially embarrassing, are likely to show greater autonomic reactions to negative stimuli. (In a crude analogy, suspenseful music and unsettling camera angles tend to make you jump higher when the cinematic equivalent of "threatening images" appear.)

An argument of this form suggests that (at least some fraction of) the (already modest) statistical effect of the physiological variables on political opinion might not reflect individual "dispositions" at all (whether innate or acquired), but rather might be the result of greater social distance (from the experimental setting) for a significant fraction of the people at one end of the political spectrum being tested.

Despite my skeptical comments, it seems to me that this work is interesting and worthwhile. It's entirely plausible that political attitudes are associated with "dispositional temperaments", and it's also plausible that "dispositional temperaments" owe something to nature as well as nurture. But it seems to me that it's exactly when theories are plausible that we should be most scrupulous in examining the evidence: as Dick Hamming used to say, "Beware of finding what you're looking for".

Dan Lufkin said,

February 15, 2010 @ 5:26 pm

Just offhand, it looks as though any selection process that ends up with 50% college-plus education has got some fundamental weakness somewhere.

[(myl) The authors write: "These distributions are generally unremarkable except perhaps for the high percentage of participants with at least a college degree—a function no doubt of the population being drawn from a college town as well as of our practice of screening for individuals with substantial interest in politics (a group more likely to be well-educated)."

I wonder if it's really true that interest in politics correlates substantially with degree of education — that's not what I would have guessed, based on personal experience. But anyhow, you have to give the authors credit for going beyond the usual experimental subject pool of undergraduates participating for course credit.]

On the other hand, I must say that my personal experience with conservatives validates the finding of a low disgust threshold. They tend to disgust easily and stay disgusted longer by many aspects of life.

[(myl) I guess it depends on what you mean by "conservative". I grew up with conservatives who had low expectations for their fellow humans, but generally responded to the confirmation of their prejudices with amused tolerance rather than disgust.]

ilana said,

February 15, 2010 @ 5:45 pm

Hi Mark.

You should be able to enlarge each page of the copy you've already linked using the zoom function of your browser (tested with firefox and chrome on mac – some older browsers may break page formatting when you zoom). The text of each page of the document is also reproduced (unformatted) in a box at the top of the corresponding web page.

Ewout ter Haar said,

February 15, 2010 @ 5:51 pm

A difference of the log of 0.0125 means that they are measuring differences in conductance of the order of 10^0.0125 = 3% (1% if its the natural log).

As you said, those are pretty small changes they are measuring, compared to the order of magnitude changes when people cough, stand up, etc.

Mr Fnortner said,

February 15, 2010 @ 6:18 pm

At the link given a panel displays at the top of every page, in my browser at least, titled "Unformatted Document Text" in which the entire page of the original document is presented as a stream of text in full size. This may prove useful. Alternatively, one could cut and paste any page of interest into a fully featured word processor and increase the type size.

[(myl) Yes, with a large amount of labor, a readable version could be (re-)constructed. But why?]

Carl Zimmer said,

February 15, 2010 @ 7:09 pm

The University of Minnesota psychologists Jonathan C. Gewirtz and Bruce N. Cuthbert wrote into Science about the paper and also raised the possibility that unfamiliar social environments are playing a role:

"If such speculation were justified, then we would predict that the results would be reversed if the experiment were repeated in a context that is particularly threatening to liberals, such as a gun show. Until this prediction is put to the test, it is safer to assume that political attitudes are related to people's responses to threat under specific circumstances rather than to a phenotypic difference in physiological responsiveness to threats in general."

Now *that's* an experiment I'd love to watch.

http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/eletters/321/5896/1667#12395

Ran Ari-Gur said,

February 15, 2010 @ 11:32 pm

I imagine that most IRBs are quite happy with experiments being conducted in contexts that are particularly threatening to conservatives, as long as the term for such contexts is "carefully controlled academic laboratory settings". By contrast, referring to contexts that are particularly threatening to liberals as "gun shows" seems less likely to win them over.

[(myl) Doing ethnography at gun shows would be fine. Bringing liberals to gun shows and attaching electrodes to them, not so much. Frankly, I doubt that the gun show organizers would be all that enthusiastic either. But you could reverse the polarity by doing the study somewhere like Liberty University or Regent University, starting (for example) with the theory that conservatism is a more independent and stoical sort of ideology, whereas liberalism tends to arise among people who want nanny-state protections because they don't have the grit to stand up to threats on their own.]

uberVU - social comments said,

February 16, 2010 @ 8:54 am

Social comments and analytics for this post…

This post was mentioned on Twitter by PhilosophyFeeds: Language Log: Physiological politics http://goo.gl/fb/suSz…

Matthew said,

February 16, 2010 @ 9:24 am

ctrl+ to enlarge font on a pc browser.

Nathan said,

February 16, 2010 @ 10:25 am

As usual with stories involving statistics, I see the tendency here (often remarked on at Language Log) to turn a small but statistically significant difference in group measurements into a sweeping statement about all individuals in a group. It's interesting how our monkey brains do that.

E. said,

February 16, 2010 @ 12:24 pm

I've always thought psychopolitical claims like this were bunk, based on myself: I sometimes feel physically ill over "threatening" photos(at least ones involving injury), I jump if I see something odd at the edge of my visual field(which often turns out to be a plastic bag or leaf), and unusual noises often make me start sweating; after these stimuli pass it takes several minutes for my heart rate and breathing to get back to normal. (I also get test anxiety, which means I'd probably feel fairly on-edge if experimented upon.) Nonetheless, I'm very far left and opposed to what this study calls "protective policies".

Kenny V said,

February 16, 2010 @ 12:42 pm

This seems to follow on the heels of the work of Jonathan Haidt, which seeks to describe the differences in the values/morals of liberals and conservatives, one of the findings of which was that conservatives value "purity" (i.e. absence of disgust) much more highly than liberals; as well as the recent philosophy of Martha Nussbaum (Hiding From Humanity: Disgust, Shame, and the Law 2004, and From Disgust to Humanity: Sexual Orientation and the Constitution 2009), wherein she argues that disgust is one of the main contributing factors in the resistance to gay marriage.

Intuitively it makes sense. I wonder if these scientists are merely attempting to empirically confirm these lines of thought. It seems to me, however, (not that I am any expert) that a better method than this purely physical-response method would be simply to ask people to rate their own feelings about things. The reduction of an extremely complex set of human mechanisms that comprise our reactions to things and subsequent views about them to simple physiological responses doesn't sit well with me.

[(myl) It's an interesting fact, often noted here, that many people seem to feel that if a psychological phenomenon can be measured physiologically, so that it's shown to be "in the brain" as well as "in the mind", that this makes it somehow more likely (or even certain!) to be genetically determined/innate.

This is a peculiar connection, since it seems to apply even in the thinking of materialists, for whom every psychological phenomenon is somehow "in the brain".]

Nick Lamb said,

February 16, 2010 @ 2:09 pm

and the stranger for the fact that we know the mind definitely has considerable direct power over parts of the body which are far more remote from it than the brain. Your mind is definitely capable of inducing otherwise unexplained (but quite real) rashes for example.

I'd characterise the current state of most brain scanning type research as equivalent to you noticing that when you a very compute-intensive program on your PC the fan spins faster and makes more noise (note to those at home, your PC may or may not exhibit this behaviour depending on numerous factors). "So what?" seems very often to be the most reasonable reaction to these studies.

ThomasH said,

February 16, 2010 @ 2:19 pm

In addition my question would be why an inate feer factor (if there is such a thing) makes "conservtives" fear terroirist and criminals who can be deterred by gun ownership but not global warming and gun bearing friends and neighbors?

E. said,

February 16, 2010 @ 2:43 pm

@Thomas H: It might have something to do with the relatively long-term impersonal nature of global warming– it doesn't have the immediacy of someone holding a gun to your head. As for why "gun bearing friends and neighbors" are less scary than terrorists and criminals, it's probably an ingroup/outgroup thing.

Another idea: could having a stronger emotional reaction to pictures of gory injury actually be linked to pacifism, empathy, and related "liberal" values?

Spell Me Jeff said,

February 16, 2010 @ 3:20 pm

Even if we take the evidence at face value, I don't see how it points to a causal relationship. It's equally likely that whatever produces political views also contributes to certain physiological responses.

Messing up correlation and causation is the great bugbear of the popular media. Seems to me too, if you want some trivial research results to get you some attention, you might be willing to provide fodder for such gaffes.

Forrest said,

February 16, 2010 @ 3:47 pm

I'm glad somebody mentioned Jonathan Haidt – the similarity to his work was going to be the bulk of my comment, but I can see that's already been brought up.

I find it a little odd that liberals are supposed to be unafraid of disturbing stimulus, and as a result want more "protective policies." Especially that unafraid lefties want tighter control over the guns that they're less frightened by. I think the reason that the left is almost synonymous with gun control is a desire to be protected from people who would acquire guns and then misuse them; this seems a bit at odds with the less fear response notion. Of course you could rephrase things as conservatives wanting guns to protect themselves from dangerous criminals, which does fit the fear-inducement part of the hypothesis a bit better.

I'm also a little skeptical that there could be gene for being aligned with one or the other political party. That's probably a bit unfair of me, and might even be drawing the arrows of causation backwards, but I'm still incredulous. Haidt describes a set of moral domains and says that people feel some of these more or less strongly, so that the sum total of their moral makeup gives them an affinity for one or the other end of the political spectrum. But I wonder how this type of research would treat political opinions that don't easily fall under the "left/right" dichotomy?

required said,

February 16, 2010 @ 7:01 pm

What I find interesting is the conclusions drawn from the test.

From the Science article we can conclude (with the same confidence) that those opposed to "protective measures" are unsympathetic towards other people and less attuned to their environment .

The blink amplitude test is just pointless for the results Oxley, et al use it to obtain. Higher amplitude startle response in an individual correlates with fear, but relative amplitudes across individuals does not indicate which are more fearful. This may be why there was not significant correspondence with bivariate analysis. At best what Oxly, et al are describing is a test (assuming statistical significance, a problem) which shows that those opposed to "protective measures" are less responsive to stimuli.

Given the 3 "threatening pictures (a very large spider on the face of a frightened person, a dazed individual with a bloody face, and an open wound with maggots in it) it doesn't seem Oxley, et al were actually testing threatening images as much as empathy. If one wanted threatening images one would instead use a large spider or the barrel of a gun pointing at viewer, something which actually might be seen as threatening to the viewer.

a straight PDF of the disgust paper can be downloaded from a link here:

http://www.allacademic.com/one/prol/prol01/index.php?cmd=prol01_search&offset=0&limit=5&multi_search_search_mode=publication&multi_search_publication_fulltext_mod=fulltext&textfield_submit=true&search_module=multi_search&search=Search&search_field=title_idx&fulltext_search=The+Ick+Factor%3A+Disgust+Sensitivity+as+a+Predictor+of+Political+Attitudes

Aviatrix said,

February 16, 2010 @ 7:45 pm

A military base would seem to be the most obvious opposite facility to the university lab at which to test the uneasiness at test surroundings bias.

D.O. said,

February 16, 2010 @ 9:55 pm

Here you can download pdf of the conversation-starter.

[(myl) Thanks! As promised, I'll blog about it as time permits.]

Graeme said,

February 17, 2010 @ 7:44 am

I'm no social scientist, but couldn't cause-effect run the other way? Eg someone acculturated in a 'conservative' environment to be wary and fear the unknown may thereby come, mentally and physically to reflexively respond negatively to unusual or unexpected stimuli.

As E.Said said, the headlines that people who are more easily threatened are more likely to be conservative fail the 'look around you' test. I and many other 'liberals' of my acquaintance feel more vulnerable than the conservatives we know. You might as well say that this maps onto a desire for collective protections, a welfare state model, as to take this research and imply that progressives are innately more trusting.

ps – I'm a relatively newbie here. So forgive the impertinence. But I am wondering about the regular threads covering science in the news, and nature vs nurture. How do they fit into 'Language Log'? (Aside from the fact that Prof Liberman et al are ardent and exacting analysts on these topics?)

J. Goard said,

February 17, 2010 @ 8:40 am

I'm with Forrest in being majorly surprised that favoring more gun control would correlate with a higher threshold for fear. Among my many anti-gun friends and acquaintances, many have been unfamiliar with guns and expresed considerable nervousness at the idea, say, of keeping a loaded handgun in their nightstand. Conversely, among my many pro-gun friends and acquaintances, it's hard to think of anybody who ordinarily expressed fear about criminals breaking in, except perhaps for one friend for a short time after he was in fact a burglary victim. It seems clear to me that the antigun view owes most of its power to an inability to get over the visceral reaction to a gun, and thus reason coolly about cause-and-effect. I guess I could just be projecting my own personality, which is very low in neuroticism (not disturbed by holding a spider, treating an open wound, seeing gay porn, eating balut, etc).

Now, the conservative side does strike me as overly neurotic about the likelihood of government taking their guns away, but that seems like a rather different issue, a reflection of the nearly-universal pessimism about the political trajectory. (Too many people I know seem to think either that all MSM except Fox News is extreme left, or else that it's all extreme right, period.)

Stephen Jones said,

February 17, 2010 @ 4:17 pm

The point is that the NRA has successfully sold the gun as part of a defence of individual freedom. There is also the simple fact that there are more guns in rural areas, which now tend to be Republican.

Descriptive and Bivariate Statistics | The Glaring Facts said,

August 3, 2010 @ 9:50 pm

[…] « IR Thoughts Statistics for Business and Economics « Khmer Campus – for unde.. Language Log » Physiological politics Data Analysis Part 1: Database Management, Distributions, and Bivariates &l.. A Little Primer […]