David Brooks, Social Psychologist

« previous post | next post »

According to David Brooks, "Harmony and the Dream", NYT, 8/11/2008:

The world can be divided in many ways — rich and poor, democratic and authoritarian — but one of the most striking is the divide between the societies with an individualist mentality and the ones with a collectivist mentality.

This is a divide that goes deeper than economics into the way people perceive the world. If you show an American an image of a fish tank, the American will usually describe the biggest fish in the tank and what it is doing. If you ask a Chinese person to describe a fish tank, the Chinese will usually describe the context in which the fish swim.

These sorts of experiments have been done over and over again, and the results reveal the same underlying pattern. Americans usually see individuals; Chinese and other Asians see contexts.

When the psychologist Richard Nisbett showed Americans individual pictures of a chicken, a cow and hay and asked the subjects to pick out the two that go together, the Americans would usually pick out the chicken and the cow. They’re both animals. Most Asian people, on the other hand, would pick out the cow and the hay, since cows depend on hay. Americans are more likely to see categories. Asians are more likely to see relationships.

Those who've followed our previous discussions of David Brooks' forays into the human sciences ("David Brooks, Cognitive Neuroscientist", 6/12/2006; "David Brooks, Neuroendocrinologist", 9/17/2006) will be able to guess what's coming.

In this case, Mr. Brooks has taken his science from the work of Richard E. Nisbett, as described in his 2003 book The Geography of Thought: How Asians and Westerners Think Differently and Why, and in many papers, some of which are cited below. I was familiar with some of this work, which has linguistic aspects, and so I traced Brooks' assertions to their sources. And even I, a hardened Brooks-checker, was surprised to find how careless his account of the research is. The relation between Brooks' column and the facts inspired me to model my discussion after the Radio Yerevan jokes that arose in the Soviet Union as a way to mock the pathetically transparent spin of the Soviet media:

Question to Radio Yerevan: Is it correct that Grigori Grigorievich Grigoriev won a luxury car at the All-Union Championship in Moscow?

Answer: In principle, yes. But first of all it was not Grigori Grigorievich Grigoriev, but Vassili Vassilievich Vassiliev; second, it was not at the All-Union Championship in Moscow, but at a Collective Farm Sports Festival in Smolensk; third, it was not a car, but a bicycle; and fourth he didn't win it, but rather it was stolen from him.

Question to Language Log: Is it correct that if you show an American an image of a fish tank, the American will usually describe the biggest fish in the tank and what it is doing, while if you ask a Chinese person to describe a fish tank, the Chinese will usually describe the context in which the fish swim?

Answer: In principle, yes. But first of all, it wasn't a representative sample of Americans, it was undergraduates in a psychology course at the University of Michigan; and second, it wasn't Chinese, it was undergraduates in a psychology course at Kyoto University in Japan; and third, it wasn't a fish tank, it was 10 20-second animated vignettes of underwater scenes; and fourth, the Americans didn't mention the "focal fish" more often than the Japanese, they mentioned them less often.

The research in question was reported in T. Masuda and R.E. Nisbett, "Attending holistically vs. analytically: Comparing the context sensitivity of Japanese and Americans", J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 81:922–934, 2001.

The subjects were 36 Americans at the University of Michigan and 41 Japanese at Kyoto University, who "participated in the experiments as a course requirement". The subjects each watched 10 animated vignettes of underwater scenes, where "Each scene was characterized by having 'focal fish,'which were large and had salient colors and shapes, moving in front of a complicated scene".

After a vignette was presented twice, the subject was asked “What did you see in the animation? Please describe it, taking as much as 2 min.” The subjects' oral responses were recorded, transcribed and coded.

The data were coded as belonging to one of the following categories: (a) focal fish, (b) background fish, (c) active animals, (d) inert animals, (e) plants, (f) bubbles, (g) floor of scene, (h) water, and (i) environment. … The categories were grouped into four superordinate categories. Focal fish remained an independent category. Background fish and active animals were grouped and named active objects, representing peripheral but moving objects. Inert animals and plants were categorized as inert objects. Finally, bubbles, floor of scene, water, and environment were categorized as background.

Here's a table of the results:

Note that each Japanese subject actually mentioned one of the focal fish, on average, 130.32 times in describing 10 vignettes — an average of 1.3 "focal fish" mentions per vignette — while each American subject mentioned one of the focal fish merely 117.91 times on average across 10 vignettes.

Now, to be fair to David Brooks, the authors found another way of looking at the data that accords better with what they hoped to prove. If you collapse everything down to two categories — basically the moving stuff and the stationary stuff — and look only the subject of the first sentence of each description, you find that the Americans did feature the "salient objects" somewhat more often, on average, while the Japanese did feature the "field" more often.

This research is described on pp. 89-90 of Nisbett's book; as far as I can tell, the experiment has never been replicated with Chinese or other Asian subjects (though if I'm wrong, please feel free to tell me in the comments).

Question to Language Log: Is it correct that when the psychologist Richard Nisbett showed Americans individual pictures of a chicken, a cow and hay and asked the subjects to pick out the two that go together, the Americans would usually pick out the chicken and the cow, since they're both animals, whereas most Asian people would pick out the cow and the hay, since cows depend on hay?

Answer: In principle, yes. But first of all, it wasn't the psychologist Richard Nisbett, but rather the psychologist Lian-Hwang Chiu. And second, it wasn't a representative sample of Americans and Asians, but rather some fourth and fifth graders from rural Indiana and rural Taiwan. And third, the American kids didn't usually make their choices on the basis of a shared named category like "animal", but rather they did this about 18% of the time, on average, while the Chinese kids did it about 12% of the time. And fourth, the Chinese kids didn't usually make their choices on the basis of functional interdependence, but rather they did this about 43% of the time, on average, while the American kids did it about 21% of the time.

The source is Lian-Hwang Chiu, "A cross-cultural comparison of cognitive styles in Chinese and American children", International Journal of Psychology 7: 235-242, 1972.

The subjects were "221 fourth and fifth grade children selected from the rural communities in the northern part of Taiwan" and "316 children of same grades sampled from the rural districts in the north-central part of Indiana". They were given a "28-item cognitive style test" where

Each item consisted of three pictures representing human, vehicle, furniture, tool, or food categories. The task for the subject was to select any two out of the three objects in a set which were alike or went together and to state the reason for his choice.

Each response was classified into one of the following categories:

(1) Descriptive — similarities identified on the basis of manifest objective attributes.

(a) Descriptive-analytic — responses denoting observable parts of an item; e.g., classifying human figures together "because they are both holding a gun".

(b) Descriptive-whole — similarities based on the total objective manifestations of the stimuli; e.g. grouping human figures together "because they are small".

(2) Relational-contextual — similarities identified on the basis of functional or thematic interdependence between the elements in a grouping; e.g., classifying human figures as similar "because the mother takes care of the baby."

(3) Inferential-categorical — similarities identified on the basis of inferred characteristics of the stimuli.

(a) Functional — items are grouped on the basis of inferred use; e.g., a saw and an ax are grouped together "because these are things to cut".

(b) Class-naming — classification on the basis of class membership; e.g., and apple and a banana are selected "because they are fruits."

(c) Attribute selection — items classified on the basis of an inferred or non-manifest attribute; e.g., a boat and a jeep are grouped together "because they both have a motor".

(d) Location — inference as to where an item belongs geographically; e.g., a cow and a horse are grouped together "because they both live on a farm".

And here are the results (click on the table image for a larger version):

This is the only way the results were scored — there is no separate tally that would correspond to Brooks' statement that

… the Americans would usually pick out the chicken and the cow. They’re both animals. Most Asian people, on the other hand, would pick out the cow and the hay, since cows depend on hay.

This research is discussed on pp. 140-141 of Nisbett's book. As far as I can tell, this particular experimental paradigm has never been replicated with any other populations of Americans or Asians. (Again, better information is welcomed in the comments.)

Exercise for the reader: Determine how much overlap there probably was between Chinese and American kids in each of Chiu's coding categories, based on the means and standard deviations given. Express your answer in terms of the probability that a randomly chosen Chinese kid would give more/fewer answers of a given type than a randomly chosen American kid.

You'll find that some of the differences are fairly large, in this way of looking at things, though there is still quite a bit of overlap.

Question for Language Log: Is it correct that these sorts of experiments have been done over and over again, and the results reveal the same underlying pattern. Americans usually see individuals; Chinese and other Asians see contexts.

Answer: In principle, yes. But first of all, depending on how the experiments are done and who the subjects are, the effects are sometimes small or non-existent; and second, in some of the experiments, young Asians show as much tendency to categorize as Americans, or even more; and third, "Asian" behavior is found in some other groups of subjects, for example working-class Italians; and fourth, nearly all the experiments are done with words, and when you test bilingual Chinese subjects in both English and Chinese, about half the effect sometimes goes away in the English version of the test. [And, I should add, an increased disposition to group things categorically (or "abstractly") rather than thematically (or "concretely") has been implicated in the world-wide trend towards higher IQ scores known as the "Flynn effect".]

I'll take a look at three papers.

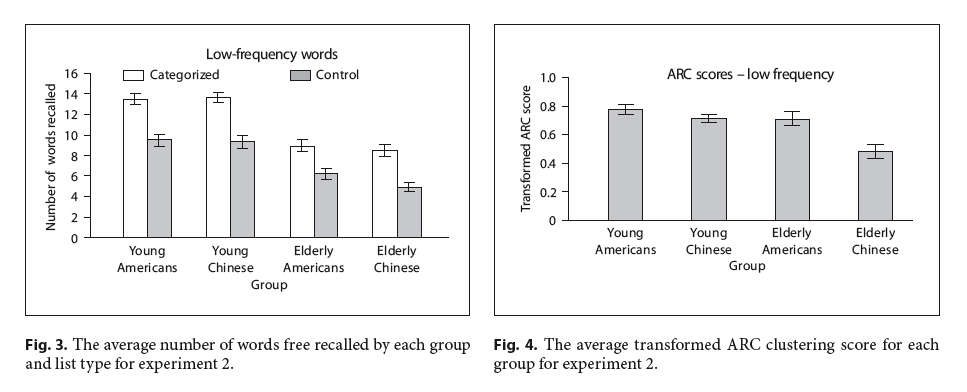

Let's start with Angela Gutchess, Carolyn Yoon, Ting Luo, Fred Feinberg, Trey Hedden, Qicheng Jing, Richard E. Nisbett, Denise C. Parke, "Categorical Organization in Free Recall across Culture and Age", Gerontology 52(5): 314-323, 2006.

Young adults (ages 18–22) and elderly adults (ages 60–78) were recruited and tested in Ann Arbor, Mich., USA, or Beijing, China, with 32 participants in each of the groups. […]

Two lists of 20 words were created: one consisting of unrelated words, and the other consisting of words related by category. For the related list, five items were drawn from each of four categories (fruits, internal organs, times of day, chemical elements) deemed to be equivalent across age and culture. The strongest exemplars (e.g. ‘apple’ for the category ‘fruit’) were avoided to prevent correct guessing of items when participants could not recall items from the related list. Whenever possible, the same category exemplars were included in the American and Chinese lists; however, the response distributions across cultures made it necessary to use different exemplars across cultures in some cases, but the same categories were always used. […]

Participants studied two lists, each containing 20 words arranged in a randomized order for each individual. Words were presented simultaneously aurally, through headphones, and visually, on a computer screen, in the participant’s native language (English or Mandarin Chinese). Words were presented visually for 4 seconds each, with a 1-second blank display before the next item. At the conclusion of the list, there was a 1-min retention interval, filled with a written subtraction by 7’s task. Participants then had 2 min to recall all the words they could remember, in any order, into a tape recorder. The procedure was then repeated for the second word list. The control list always preceded the list of categorized words. This was done to avoid any possible group differences in the expectation of relationships between the control words, which participants may be more prone to search for if they were to encode the related word list beforehand.

But it turned out that neither the young people nor the old people showed any Ann-Arbor-vs.-Beijing differences in recall as a function of categorization:

The authors looked at the data a different way, to quantify the subjects' tendency to recall items in an order that reflected category membership. Here's the paper's description of the analysis:

For the clustering analysis, the number of items generated in succession from a single category was coded. If repetitions occurred within same-category clusters, they were omitted from the clustering analysis, but did not mark a break in the cluster. Adjusted ratio of clustering (ARC) scores are a common measure of clustering, considered suitable across a range of numbers of items recalled. An ARC score of 1 denotes perfect clustering (i.e. all items from a single category are recalled together before moving to the next category), whereas a score of 0 denotes clustering at the level of chance (i.e. item order is ‘zero-order’ or entirely random, given a fixed set of mentioned items). Negative ARC scores (except in rare cases, bounded at –1) are possible when less categorization occurs than by chance (i.e. items from different categories tend to be output adjacent to one another). Comparing across groups using standard statistical techniques requires not only that the means of ARC distributions be the same for any number of mentioned items – and they are, in fact, always zero – but that the standard deviations be the same as well, which they are not. For example, with four categories of five items each, we can compute the ‘by chance’ ARC distribution for any number of mentioned items; for all 20 mentioned, the ARC standard deviation is 0.148, while for 6 items, it is 0.537, or 3.5 times greater. In this way, ARC scores do, in fact, depend upon the number of items recalled: because conditional distributions can differ across groups when recall performance differs, average ARC should not be used for between group comparisons when groups differ on number of items recalled. It is plainly inappropriate to use standard t-type means-based tests, then, on the raw computed ARC score. To address this problem, we transformed the conditional (on number of items recalled) ARC distributions to conform to the same distributional family, one as close as possible to the calculated, empirical ARC distributions. We henceforth refer to these individual level clustering measures as transformed ARC scores.

Here's the result — the young Chinese actually had a higher ARC score than the young Americans, though not significantly so, while the old Chinese had a slightly lower ARC score than the old Americans:

… the young Chinese (mean = 0.90, SD = 0.15) had transformed ARC scores that did not differ significantly from the young Americans (mean = 0.82, SD = 0.28), t (62) = 1.51, p = 0.14, while the elderly Chinese (mean = 0.48, SD = 0.50) had disproportionately lower transformed ARC scores relative to the American elderly (mean = 0.70, SD = 0.31), t (62) = 2.11, p < 0.04.

This essentially negative result surprised the researchers enough that they did the experiment over again:

The surprising disconnect between free recall and categorical clustering found in experiment 1 could reflect the strong categorical associations of the list items. The strong associations could make the categorical organization apparent and evident as a possible strategy, consistent with the finding of high transformed ARC scores. Even though the organizational scheme may not be commonly employed as a spontaneous strategy in some groups, the salience of the manipulation may have contributed to the finding in experiment 1. In order to address this possibility, in experiment 2 we selected words less strongly associated with the categories and assessed memory and categorical clustering in new samples across age and culture. This approach afforded the benefit of a more subtle manipulation that might allow cultural biases to emerge more clearly.

But in fact the results of the second experiment were not very different (click on the image for a larger picture):

This time the cultural difference came out statistically significant when the groups of all ages are treated together, though barely so — the ARC for the Americans were mean = 0.74, SD = 0.33, while for the Chinese they were mean = 0.60, SD = 0.38. They don't tell us what the statistical tests showed for the groups considered separately, but eyeballing the graph suggests that for the young people, the effect of "culture" was still not statistically significant.

The authors are resilient in insisting that these results support the theories of American/East-Asian cultural differences, at least to some extent:

Overall, our results provide some support for the notion that East-Asians use categories as an organizational strategy based on taxonomic categories less than do Americans. Whereas past studies demonstrated this effect in young adults, the difference was demonstrated primarily in elderly adults in the present experiments. The careful selection of words, equated across culture for both familiarity of items as well as overall structure of the category, may have prevented the expression of cultural differences in the young. […]

In conclusion, the present studies suggest that cultural differences in the use of categories as an organizational strategy are more prominent for older adults, with East Asians less likely to organize their recall by category. It is unlikely these effects are due to cohort differences due to careful sampling and similar findings of cross-cultural differences in young adults . Instead, our findings reflect the bias to process information less categorically in East-Asians, with the effect manifest in the older adults who have accrued years of experience in the culture. Despite the overwhelming effects of neurobiological aging, elderly adults express the signature of their culture in their use of cognitive strategies.

An alternative interpretation, which the authors reject because it disagrees with their view of the literature in this area overall, would be that Chinese culture is changing in a direction that makes its effect on this particular task more like the effect of American culture.

For our second paper in support of this joke, let's take a look at Nicola Knight and Richard Nisbett, "Culture, Class and Cognition: Evidence from Italy", Journal of Cognition and Culture 7: 283-291, 2007.

East Asians have been found to reason in relatively holistic fashion and Americans in relatively analytic fashion. It has been proposed that these cognitive differences are the result of social practices that encourage interdependence for Asians and independence for Americans. If so, cognitive differences might be found even across regions that are geographically close. We compared performance on a categorization task of relatively interdependent southern Italians and relatively independent northern Italians and found the former to reason in a more holistic fashion than the latter. Furthermore, as it has been argued that working class social practicesencourage interdependence and middle class practices encourage independence, we anticipated that working class participants might reason in a more holistic fashion than middle class participants. This is what we found – at least for southern Italy.

They tested final-year students in four high schools in Italy. There were two schools with a "classics" orientation, likely to be attended by upper socio-economic status students; one of them was in Milan (in the industrial north of Italy) and the other was in Sicily. And there were two schools of the category known as Istituti Professionali di Stato per l’Industria e l’Artigianato, or "State Professional Institutes for Industry and Crafts", likely to be attended by working-class students. Again, one of the schools was in the north near Milan, while the other was in Calabria, in the south of Italy.

The subjects were given "a printed list of twenty items, each composed of three words (e.g., Monkey, Panda, Banana)", and asked to circle the two that "go together". In seven of the twenty items, the words could be grouped by categorical relations (Monkey and Panda) or by thematic relations (Monkey and Banana). The other 13 items were fillers. "Meaningless" pairings (e.g. Panda and Banana) were ignored. The rest of the responses were coded as 1 (thematic) or 0 (categorical), summed, and divided by seven, to yield a score between 0 and 1, with higher scores reflecting a greater tendency towards thematic answers.

Here are the results:

Figure 1. Proportion of thematic pairings by school and SES. Bars represent ± one standard error.

Thus southern Italians, especially the lower-class ones, are apparently quite Asiatic.

OK, the few of you that are still following along can splash some cold water on your face, pour another cup of coffee, and check out the third and last paper presented in support of our third Radio Yerevan joke: Li-Jun Ji,, Zhiyong Zhang, and Richard E. Nisbett, "Is it culture, or is it language? Examination of language eff ects in cross-cultural research on categorization." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 87: 57-65, 2004.

This paper brings in our old favorite, the Sapir-Whorf "linguistic relativity hypothesis", the concepts of "compound" vs. "coordinate" bilinguals, and for some other reasons as well is worth a longer discussion that I have the time or patience to give it this morning.

Again, there are two studies reported, probably because the results of the first study were problematic from the researchers' point of view.

In Study 1, the subjects were 119 Chinese students at Beijing University, 131 Chinese students at the University of Michigan, and 43 "European American" students at Michigan, who received course credit. (One thing that worries me about many of these studies is the fact that some of the students, presumably recruited from the researchers' own classes, were familiar with the themes and conclusions of the research, and thus knew how they were "supposed" to respond. This property is not always equally distributed among the "cultural" categories.)

The test was similar to the one used in the Italian experiment just described: participants were shown 20 sets of three words, and asked to indicate which of the two of each set were most closely related, and why.

We used very simple words in the task so that it was easy for bilingual Chinese to understand the task in English. There were 10 sets of test items and 10 sets of fillers. The three words in each testing set could be grouped on the basis of thematic relations, categorical relations, or neither. Participants’ groupings were coded as relational if they suggested an object–context or subject–object relationship, such as monkey and bananas, shampoo and hair, or conditioner and hair. Groupings were coded as categorical if they suggested shared features or category memberships, for example, monkey and panda or shampoo and conditioner. Similarly, participants’ explanations were coded as either relational (e.g., “Monkeys eat bananas”) or categorical (e.g., “Monkeys and pandas are both animals”). Examples for filler items included child–teenager–adult and Monday–Wednesday–Friday.

Within each of the 10 testing sets, there were 3 possible ways for participants to select two items. In total, there were 30 possible ways of grouping, 14 of which were coded as relational (such as policeman and uniform, and postman and uniform) and 11 of which were coded as categorical (such as policeman and postman). Thus, the stimuli were biased toward relational grouping.

The Americans were tested in English, while half of the Chinese were tested in Chinese, and half in English.

Here are the results in graphical form:

The first thing to notice is that none of these subjects are nearly as "relational" as the Sicilian vocational-school subjects were. The Sicilian kids gave a relational answer 85.6% of the time, on average — if the Chinese students had answered that way here, they'd presumably have given a relational answer on 8.56 of the 10 test questions, and a categorical answer on 1.44, on average, yielding a score of 8.56-1.44 = 7.12 (even without allowing to any effect of the test's bias in favor of relational answers). But the highest score for any of the Chinese groups was about 3.5.

Then we can notice what obviously struck the researchers most strongly — testing Mainland and Taiwan Chinese students in English eliminates roughly half of the difference between them and the American students. (The Hong Kong and Singapore students behaved about the same in both languages.) This was also true of the explanations offered by the students for their choices:

The authors offer two different explanations for this effect:

Why does language of testing affect categorization? There are at least two explanations. One could be that structural differences in English and Chinese lead to different reasoning styles, such that certain features of the Chinese language make people think in a relational way whereas certain features of the English language make people think in a categorical way. The other explanation does not pertain to language per se. Instead, it is likely that the language used for a task makes certain ways of reasoning more accessible by activating representations that are common in a particular culture.

It also seems possible that something much more superficial is going on: perhaps there is something about the particular set of ten word-triples used in this test, either in their form or in the way they're written, that biases the choice differently in the two languages. Unfortunately, the specific list of words used is among the details that should be reported for such studies, but are not.

The authors also worried that the language effects might be due to some differences in the kinds of students selected for the study. So they did the study again, using 59 Hong Kong University students (52 of whom were women) and 57 Beijing University students (29 of whom were women), and using a within-subjects design, with each subject taking the test twice, once in English and once in Chinese.

The test was also a different one, designed to eliminate the bias in favor of relational groupings: there were 8 test triples that each allowed only one way to be relational and one way to be categorical (at least in the experimenters conception of the relations and categories involved). The results were basically the same:

Note that despite the less intrinsically biased nature of the material, the Mainland subjects in this case showed a much larger bias in the relational direction — a difference of 5 on 8 choices, as opposed to a difference of about 3.5 on 10 choices. This quantitative instability of the results from test to test, even for the same subject pool (in this case students at Beijing University), suggests that the specific choice of test words makes a big difference. Given this apparently very large effect, the quantitative comparison of results across languages seems very problematic to me. This also underlines how unfortunate it is that the norms of this discipline apparently don't include publishing a complete list of the materials used in an experiment.

Overall, it's certainly clear that there's something going on here, and that it has something to do with a differential propensity to group words and pictures by taxonomic categories as opposed to by functional relationships. But the group differences are generally moderate and quantitatively erratic, and I worry about the apparent commitment of the researchers in this field to maintain their initial conceptual framework, no matter how the experiments come out.

As for David Brooks, he wants to use this stuff as the scientific foundation for the hypothesis that western societies are fundamentally and essentially individualist while Asian societies are fundamentally and essentially collectivist. That might be true, but it's a long and winding road to that conclusion from the complex and equivocal results of various experiments on how people group various triples of words and pictures, or describe undersea scenes. And we should be wary of following David Brooks too far down that road, given that he can't be bothered to keep straight who did which experiments, or whether the subjects were Chinese or Japanese, or whether it was the Americans or the Asians who more often mentioned the focal fish, or essentially any of the evocative details that he loves to use to bring his ideas to life for his readers.

Rob P. said,

August 13, 2008 @ 9:36 am

The researchers in the final study guesses that structural differences may account for the categorical groupings in Chinese. That is plausible in that Chinese attaches categorical words to nouns (apologies for any errors in the following, it's been a long time since I studied or used Chinese), e.g., yi zhi gou (one animal-thing dog) vs. yi ge ren (one people-thing person) vs. yi kuai quian (one thing-that comes-in-lumps money). When learning Chinese in school, this factor caused me to have to think of things in terms of groupings that I would not apply in English (first language) or Spanish (second, but far from fluent language). Not sure whether a native speaker would be attuned to or influenced by this, but it could account for the difference.

Adrian Morgan said,

August 13, 2008 @ 9:38 am

Another complication in the chicken/cow/hay thing is that chickens often make their nests out of hay, so there's a relational connection between chickens and hay, just as there is between cows and hay. If I were doing the test, I'd probably go with the categorical connection and put chicken and cow together, on the grounds that the two relational connections cancel out. That tells you nothing about how much importance I place on the different types of connections. There's also the point that results may be skewed by irrelevant cultural factors, such as familiarity with farming practises (or perhaps even the nature of farming practises).

ed said,

August 13, 2008 @ 9:38 am

This may be a naive question, but have you had any response from Brooks on these critiques? I'm curious how he can defend such sloppiness.

Mark P said,

August 13, 2008 @ 9:50 am

Brooks has an opinion, so he looks for evidence to support it. That's no surprise for a columnist. But it's not such good practice for scientists.

James said,

August 13, 2008 @ 9:52 am

http://www.phillymag.com/articles/booboos_in_paradise/

In that story, a reporter calls Brooks on his errors, and his response is something like "well, I think it all rings true, but I expect my intelligent readers to be able to see through the exaggerations"

To me, it look like he relies on things "ringing true", yes, but I not on intelligent readers.

Mark Liberman said,

August 13, 2008 @ 9:57 am

Ed: This may be a naive question, but have you had any response from Brooks on these critiques? I'm curious how he can defend such sloppiness.

I doubt that he's aware of my posts, but in any case he's never responded.

As I've suggested in another connection, I imagine that his reaction would be something like that of an Episcopalian Sunday-school teacher confronted with evidence from DNA phylogeny that the animals of the world could not possibly have gone through the genetic bottleneck required by the story of Noah's ark. "I mean, lighten up, man, it's just a story."

The problem, from my point of view, is that some people take such stories seriously.

Mark Liberman said,

August 13, 2008 @ 10:02 am

@Rob P: The noun classifier system in Chinese is one possible source of linguistic influence. Another is morphological make-up: thus English policeman and fireman share a morpheme in a way that Chinese 警察 jing3cha2 and 消防员 xiao1fang2yuan2 do not.

I doubt that such effects account for all of the results, but they might well influence the results in various directions, depending on the particular set of words used.

It's for reasons like these that I think it's irresponsible not to publish the full list of test items used in such such experiments.

I also worry about the effect of Sesame Street ("One of these things is not like the others"), of typical other typical early-childhood teaching and testing methods, etc.

KYL said,

August 13, 2008 @ 11:14 am

Mark,

Thanks for your continuing efforts in this realm. People take this kind of sloppy extrapolation from "scientific studies" popularized by column writers very seriously, as it gives them a nice "objective" way to support their prejudices.

I have heard this bit about how "Asians" cannot conceive of individuality multiple times as something that has been scientifically proven. My usual response is to explain that actually, at least among the Chinese, the practice before the 20th century was that each person upon reaching the age of majority would choose a "courtesy name" for himself/herself, and that the courtesy name is supposed to represent his own conception of himself as an individual, and that is the name that everyone else (except his parents) will call him by for the rest of his adult life. This, I posit, shows that the Chinese are actually much more individualistic. This kind of argument is no better than the silliness about scientific experiments. But isn't that why folk science is so much fun?

If only the nonsense on all sides would stop.

Stephen said,

August 13, 2008 @ 11:56 am

I've heard/read (but, conveniently, can't remember where) the same "Group A connects cows and chickens while Group B connects cows and hay" thing when talking about literate vs. illiterate groups of people, except that the items were a hammer, a peeler and a potato – The literatre group picked hammer and peeler as both being tools while the illiterate group picked the peeler and the potato because you use those two together. I'm pretty sure I read this in an article in the New Yorker about the effects of literacy on society. Could it be that this fellow just couldn't help but interpret this study through the lens of whichever study this other article's author used?

[(myl) There's the "Flynn effect", discussed here, which is driven to a large extent by things of this kind.]

Ryan Denzer-King said,

August 13, 2008 @ 1:14 pm

I have to admit that I'm quite interested in this kind of research. Three things caught my eye here: the smaller differences among children (who theoretically have acquired less of cultural values than have older people), the at least equal (though it looks like significantly greater) difference among various classes as among various cultures, and the fact that bilingualism cuts the effect in half. I wish people would stick to the facts, because I feel like exaggerated claims like Brooks' devalue this kind of research within many academic circles.

Rick S said,

August 13, 2008 @ 1:19 pm

Larry the Cable Guy, meet Louann Brisendine…

Is it conceivable that the NYT planted Brooks on the op-ed page as a ringer, to mock the conservative viewpoint? If so, how discouraging that it seems to have backfired (and yet, such journalistic shadiness would deserve it).

Karen said,

August 13, 2008 @ 2:39 pm

The vanishing difference between children and older people reminds me of the interview I read with Isao Takahata, director of Grave of the Fireflies. He said that he intended people to see the boy's rebellious behavior as bringing destruction down on himself and his little sister – so that, in a way, their deaths were his own fault; but that younger Japanese viewers identified and sympathized with the boy. Not to justify Brooks, but cultures are mutable.

Mark Liberman said,

August 13, 2008 @ 2:57 pm

Karen: Not to justify Brooks, but cultures are mutable.

Yes, and cultures are different, too.

The question is whether it's in some sense scientifically established that all Asians are collectivist and all Westerners are individualist. Or even that this used to be true and now is changing. The concept is a plausible one on ethnographic grounds, I guess, but it's not clear how far the experiments on word-triple grouping and so forth really take us.

There are plenty of recent experiments of this kind that show college-aged Chinese or Japanese grouping less categorically than Americans, e.g. the Chinese-language experiments on the Beijing students in Ji, Zhong and Nisbett 2004.

From my point of view, the first problem (once we get past the carelessness with details) is that (as often) we're talking about modest differences in group averages, with lots of within-group variance, which are presented as if they were properties of all the individuals involved.

The second problem is that the experimental results seem to be all over the place, in fact, as a function of fairly small differences in experimental design, choice of subjects, etc. This leaves me with many questions about what's really going on.

Mark Liberman said,

August 13, 2008 @ 3:05 pm

Stephen: I've heard/read (but, conveniently, can't remember where) the same "Group A connects cows and chickens while Group B connects cows and hay" thing when talking about literate vs. illiterate groups of people …

You might be thinking about James Flynn's current hypothesis about the origins of the Flynn effect — quoting from the Wikipedia article:

Malcolm Gladwell's review in the New Yorker of Flynn's 2007 book What is intelligence? puts it like this:

john riemann soong said,

August 13, 2008 @ 3:37 pm

As a mere high school grad I get awfully annoyed and depressed by articles like this, in the NYT, especially with the repressiveness of the categorisations implied. (A new spin: Westerners love to categorise [people, pseudoscientifically], hurr hurr …. and avoid context …. hurr hurr).

I wonder what is Mark Liberman's stance on linguistic relativism in general? Are these papers just sloppy works in a respectable field? The acting director for the linguistics department of my new school this year is apparently a strong supporter of linguistic relativism who wishes to qualify the claims of cognitive science. I'm not sure how even a layman can be attracted to Whorfianism, an ideology based on unchecked speculation inspired by the book-study of Native American language that turned out to be ill-founded, after reading an elegantly simple eye-opener of a book like Pinker's The Language Instinct.

Specifically for the experiments mentioned here, it just smells of strong confirmation bias. (And of course, the columnist's crediting of only anglophone psychologists are conducting these studies remind me all too much of an attitude of a documentary filmmaker whose sole aim is to show the amazing strangeness of exotic peoples.) If I guessed correctly, the researchers *created* the categories before collecting their data, which just smacks me of presumptuous arrogance. THEN they go and fit the responses to these categories, looking to prove their hypothesis. This is not counting any overt cherry-picking of course. THEN they go and take these results and say, "surely this is reasonably strong proof of differences in cognition!" What a way to test cognition, when they created the categories themselves! It seems to me that they didn't bother with all sorts of controls for confounding variables, such as controlling for immigration background, multilingualism … is there any hope for this kind of "social psychology"?

In fact, is there any real scientific evidence for linguistic relativism? Contrasting "The Language Instinct" with say, "The First Idea" (a book that has been made fun of on Language Log Classic), it seems the latter has nothing but unfalsifiable speculation and interpretations compared to the hard (medically-backed) evidence of the latter? Has linguistic relativism ever addressed any of the empirical evidence for linguistic universalism, even ignoring convincing theoretical arguments like poverty of the stimulus, etc.?

Nathan Myers said,

August 13, 2008 @ 3:54 pm

It's not possible to "mock the conservative viewpoint". Anything you can come up with will be exceeded — and, indeed, completely overwhelmed — by real life. In any case, the NYT management are deeply conservative themselves, so it would amount to self-mockery.

Read Brad Delong over at http://delong.typepad.com/ to monitor how deeply into self-mockery the NYT (like the Washington Post) has descended.

Tia said,

August 13, 2008 @ 5:44 pm

Stephen may also have read Walter Ong's Orality and Literacy (or some reference to it), which is where I first encountered a description of the tendency of people who lived in non-literate societies to group things functionally, and the tendency of people in literate societies to group them abstractly.

Mark Liberman said,

August 13, 2008 @ 6:42 pm

Tia: Walter Ong's Orality and Literacy (or some reference to it) … is where I first encountered a description of the tendency of people who lived in non-literate societies to group things functionally, and the tendency of people in literate societies to group them abstractly.

The work that Ong describes (pp. 50-51 of Orality and Literacy) is the 1930s research of Lev Vygotsky and Alexander R. Luria in Kazakhstan and Kirghizia, described in Luria's Cognitive Development: Its Cultural and Social Foundations (1976).

And what Richard Nisbett says about this (p. 85 of The geography of thought) is "And the school of psychology that I find myself belatedly belonging to is the historical-cultural one established by the Russian psychologists Lev Vygotsky and Alexander Luria".

Ong emphasizes the role of literacy as such far more than Luria, who was interested in what he called "the sociohistorical evolution of mental processes", construed much more broadly.

ed kupfer said,

August 13, 2008 @ 9:01 pm

Exercise for the reader: Determine how much overlap there probably was between Chinese and American kids in each of Chiu's coding categories, based on the means and standard deviations given. Express your answer in terms of the probability that a randomly chosen Chinese kid would give more/fewer answers of a given type than a randomly chosen American kid.

Mark has referred in a few posts to this presentation of effect sizes, the probability of data point drawn from sample A being greater to that drawn from sample B. I always have trouble explaining effect sizes to non-stats people, and have been using this one of late because it is transparent and so easily interpreted. Turns out it has a name: Probability of Superiority, as outlined in Robert Grissom's book Effect Sizes for Research: A Broad Practical Approach.

seriously said,

August 13, 2008 @ 10:23 pm

Just a thought: in the "monkey, panda, banana" group, the "panda" and "banana" pairing isn't necessarily meaningless. In English, the two words sound rather alike and in a way that might appeal to some. E.g., I can imagine them in a Dr. Seuss book or in something along the lines of Subterranean Homesick Blues.

Imagethief : Olympic match-up: Brooks vs. Fallows said,

August 13, 2008 @ 10:25 pm

[…] his approachable writing style and endearing nerdy streak. Update:Speaking of "nerdy", don't miss Language Log's dissection of Brook's use of scientific studies to support his assertions. It's somewhat academic (perforce, […]

Pete Carlton said,

August 13, 2008 @ 10:45 pm

A comment I saw long ago is appropriate here:

"Kristof and Brooks appear to be competing to carve out a previously unheard-of niche in the chattersphere: the thinking person’s anti-intellectual."

Garrett Wollman said,

August 13, 2008 @ 11:20 pm

Stephen Jay Gould had a nice term for what Mark L. describes as "differences in group averages, with lots of within-group variance, which are presented as if they were properties of all the individuals involved": "The Fallacy of the Reified Mean". It seems to be a cognitive trap that humans are generally prone to. (Could you design an experiment that would measure this?)

Jon88 said,

August 14, 2008 @ 10:45 am

Agreeing with seriously said — When I saw MONKEY, BANANA and PANDA, my first reaction was that BANANA and PANDA have no vowels but A, and are thus related.

Tom Ritchford said,

August 14, 2008 @ 11:19 am

Oh, I am chortling with glee, so rare it is to see such a solid rebuttal of one of the vacuous pieces presented to us by the mainstream media as "science fact real-io trulio."

The very worst is that Brooks' article is the classic "yellow peril" scare story, gussied up with some pseudo-science and a reference to the Olympics.

Good work, Professor Liberman!

I love Language Log. | shep.ca: the writing work of Matt Shepherd said,

August 14, 2008 @ 1:08 pm

[…] Stuff like this is why: a thorough examination (and consequent trashing) of David Brooks' newest foray into the soft s… […]

Fireworks and News from Japan « Mara In Japan said,

August 14, 2008 @ 1:43 pm

[…] Language Log: David Brooks, Social Psychologist explains this New York Times' writer's oversimplification of studies on American vs. Asian psychology. […]

Sili said,

August 14, 2008 @ 4:14 pm

I don't know why you bother, but I appreciate it nonetheless. The Radio Yerevan theme really apportions as much respect to Brooks as he deserves.

I'll admit to skimming rather fast through the last bits (paying attention to your points only), but I still feel educated.

The whole collectivist and authoritarian set-up made me think that he was gonna lash out as us Europeans. It seems to be a common observation that the Danish welfare state is pretty much a (successful) realisation of the (failed) DDR dream. It'd actually be interesting to see if genuine tests for collectivity would show any correlation to state welfare (for which tax level is possibly a good proxe – with the possible exeption of Norway).

It's hardly Richard's fault, but the Nisbett is starting to make me break out in little red spots.

Idly, the phenomenon Rick S and Nathan Myers mention is known as Poe's Law.

Uly said,

August 14, 2008 @ 7:38 pm

"I've heard/read (but, conveniently, can't remember where) the same "Group A connects cows and chickens while Group B connects cows and hay" thing when talking about literate vs. illiterate groups of people, except that the items were a hammer, a peeler and a potato – The literatre group picked hammer and peeler as both being tools while the illiterate group picked the peeler and the potato because you use those two together."

Well, gee, I'd pair potato and peeler not because you use them together (I never peel potatoes if I can help it) but because they're both things you find in a kitchen.

Angela Gutchess said,

August 15, 2008 @ 12:19 am

As an author of one of the cited studies, I would like to note that some of the claims made about our paper are, in fact, in error:

1) Liberman identifies our use of a clustering measure as a “complicated re-analysis of the data”. In actuality, this analysis addresses a different aspect of memory (the organization of information) compared to the measure of the number of words recalled. The use of clusters is a classic finding in memory, and a variant of the analysis has been used over several decades.

The novel use of transformed ARC scores was intended to correct a problem with some measures used in the past. Namely, clustering measures are supposed to be independent of the amount of information recalled (in line with my point above that the measures address two different aspects of memory). This was not true for many of the extant formulas, but our measure corrects for this.

2) Experiment 2 was intended to provide a conceptual replication of experiment 1. We did not conduct it because “(the) essentially negative result bothered the researchers enough that (we) did the experiment over again” (as suggested by Liberman). Replication of results increases confidence that the effects are real, rather than just a spurious “fluke” finding. Given Libermans’s repeated calls for replication of results throughout his piece, this is a surprising misreading of our intent.

I encourage the author to engage in a dialogue with researchers studying cognition across cultures. In my opinion, you would find many points of agreement, such as the acknowledgement of the substantial overlap in cognition across cultures, the call for better understanding of the many aspects of culture (within and across nations), the need for broader and diverse theoretical perspectives, and the importance of replication (although I would argue that many of the mentioned studies do provide conceptual replications of each other).

[(myl) These are fair criticisms. I've modified my discussion of Gutchess et al. in the body of the post to be (I hope) more accurate, specifically removing some speculative negative evaluations for which I had no evidence. I included this paper primarily because its results are relatively weak, or even somewhat contrary to the general stereotype; and secondarily because the authors chose to try to explain why some of their results don't support the stereotype, rather than concluding that perhaps the stereotype is not so strong after all. I believe that this description remains valid.

I've added another post linking to some meta-analyses of quantitative IND-COL research. ]

Asian socities drive like this... | MetaFilter said,

August 15, 2008 @ 1:19 am

[…] socities drive like this… August 14, 2008 7:57 AM Subscribe David Brooks, Social Psychologist, Mark Liberman at Language Log looks at the science behind David Brook's latest column in which he […]

Michael Turton said,

August 15, 2008 @ 2:54 am

Nisbett's stuff seems to get a lot of play in the media. Research results aside, his "cultural" explanations verge on asininity. I blogged on this problem of his a couple of years ago:

Researchers perpetuate cultural stereotypes.

Excellent piece, Dr. Liberman.

Michael

Improbable Research » Blog Archive » Disentangling a fishy, confused mess said,

August 17, 2008 @ 12:02 am

[…] Radio Yerevan jokes that arose in the Soviet Union" — as demonstrated above — enlivens a very sweet piece of b.s. detection and debunking. Here is a nice little chunk of it: Question to Language Log: Is it correct that if you show an […]

OL i Beijing: Mere vrøvl fra Brooks | KINABLOG.dk said,

August 19, 2008 @ 2:22 am

[…] andet Imagethief, Peking Duck, China Law Blog, Pomfrets China, Blurring Borders og ikke mindst Language Log, der laver en grundig gennemgang af det tåbelige argument om at vesten skulle være et […]

Crispus said,

August 20, 2008 @ 8:16 am

Recently, in the last six months, read an article announcing MIT brain wave studies that indicate cultural bias. From the brief newsy articles I got the idea Nisbitt's work got some validation.

As I have lived in China more than six years, in Asia about 14 years, and teach Western Accounting, I found Nisbett's book enlightening. Once the language hurdle has been passed, the very best students, the ones that work and really try, begin to have problems solving problems as they attempt to redefine a much more encompassing problem and seek a more general solution.

In accounting, the goal is to wade through facts and words to focus on making correct decisions about the given information to solve the presented problem. This takes language skills, plus critical thinking, plus problem solving ability. Most of my students are weak in the first two, but, attempt to solve a Western problem in the Chinese way.

I observed some of same responses Nisbett did long before I read his book. Yes, I actually read it and even give away copies I buy at my own expense.

Group orientation and individual behavior are not mutually exclusive unless you see them as polar. Chinese can show a great deal of individualism within the group. I think Nisbett has identified Chinese thinking and cultural bias to be within a group context. I also feel Chinese have a sliding concept of group. At the core is the family, in today's one child Chinese world, the parents are the dominant focus. The next group context, I think of them as concentric rings, is the Middle School class. Now that some of my students are older, working and some have advanced degrees, I detect some affiliation for a university group.

I am not sure if the group context thinking is cultural, that is, has existed for centuries, or, if it is a post 1949 occurrence. Mao was a genius who exploited Chinese characteristics in his non-Marx application of Marx.

In any event, a Canadian friend, PhD., author, and sometime resident of China remarked that in all his travels in only two countries did the citizens rise to defend their country from slanderous comment, China and the U.S.

At the end of the day we all belong to one group or another.

Mary Erbaugh said,

August 21, 2008 @ 6:48 pm

Thanks, Mark, for taking on the implicitly racist orientalism of David Brooks — and for deconstructing the incredible sloppiness of Nisbett's research.

Some ideas are just to bad to go away. One is the relentless search for Sapir-Whorf type effects of grammar on world view — as separate from culture.

Mostly, the urge to stereotype a distant Other seems ideologically driven (Erbaugh 2002b.)

But experimental linguistics has tested decades worth of possible grammatical influences on cognition. The purported grammatical influences keep disappearing under careful analysis. Al Bloom claimed that the Chinese language handicapped its speakers in thinking scientifically and hypothetically. The alleged effect disappeared once Terry Au re-translated the test materials into idiomatic Chinese (Au 1983).

As several commentators to your blog have mentioned, Japanese and Chinese measure words aka noun classifiers (e.g. tiao 'elongated' for ropes or dogs) seem a promising candidate for grammatical shaping.

Yet even classifiers turn out not to effect object sorting or world view. When Mandarin, Cantonese and Shanghai Wu dialect speakers describe Chafe's experimental 'Pear Stories' film, they mention the same objects, in the same order, as English speaking Berkeley students (Erbaugh 2002a, 2006). Cantonese uses over 5x more noun classifiers per noun than Mandarin does — but the contents of the stories are the same. The difference turns out to be grammatical, not conceptual.

Additional reasons why the classifiers turn out not to have a cognitive effect: 1) about 1/2 of all nouns appear without no classifier at all in connected speech. (This is perfectly grammatical for generic or indefinite nouns). 2) Special classifiers (tiao 'elongated') turn out to be surprisingly low frequency: 95% of the Mandarin classifiers used were the general classifier. 3) The special classifiers do not form clear semantic categories (e.g. animal vs human) but highly heterogenous, overlapping sets. For example, the classifier which is often glossed as 'animal' (zhi) in fact also modifies: members of a pair, small roundish objects, watches, phonograph records, and boats. 4) The same speaker would describe the same object with several different classifiers. A goat, for example, on screen for only 7 seconds, received the 'animal', 'head' and 'elongated' classifiers.

Terry Kit-fong Au. 1983. 'Chinse and English Counterfactuals'. Cognition. 15:155-87.

Mary S. Erbaugh. 2002a. Classifiers are for specification: Complementary functions for sortal and general classifiers in Cantonese and Mandarin. Cahiers de Linguistique – Asie Orientale. 31:2;33-69.

Mary S. Erbaugh. 2002b. 'How the Ideographic Myth alienates Asian Studies from Psychology and Linguistics' in M. S. Erbaugh, ed. Difficult Characters: Interdisciplinary studies of Chinese and Japanese writing. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University, Foreign Language Publications. 21-51.

Mary S. Erbaugh and Bei Yang. 2006. Two general classifiers in Shanghai Wu dialect compared to single classifiers in Cantonese and Mandarin. Cahiers de Linguistique – Asie Orientale. 35:2;169-207.

Wednesday Round Up #28 « Neuroanthropology said,

September 10, 2008 @ 6:26 am

[…] Liberman, David Brooks, Social Psychologist Language Log takes down Brooks’ facile “collectivist mentality” […]

“Black or white”, “East or West” are not racially or culturally exhaustive. « Restructure! said,

June 26, 2009 @ 11:30 am

[…] people (including psychologists) even think that if a phenomenon occurs in both a Western society and an East Asian one (since East […]

“Easterners” are not collectivist automatons who are poor at analytical reasoning. « Restructure! said,

September 15, 2009 @ 9:08 am

[…] David Brooks, Social Psychologist by Mark Liberman at Language Log […]

Etl World News | THE LOUSY LINGUIST. said,

November 26, 2009 @ 12:34 pm

[…] Liberman "to refer to Mark Liberman's excellent manner of debunking bad journalism (see here and here for […]

I’m in New Scientist: “Beyond east and west” | Not Exactly Rocket Science | Discover Magazine said,

March 27, 2010 @ 6:14 pm

[…] Following the piece I wrote on FOXP2, this is another of those "the media says this, but here's what's really going on" pieces. It's an exploration of the supposed cultural differences between East Asians and Westerners in the ways they see and think about the world. This is a fairly controversial area and my intention was to shed a bit of light on the debate and go beyond the stereotypes that are so often inaccurately presented by the popular media (and rightfully mocked). […]

How wrong is David Brooks? | Smash Company said,

October 24, 2011 @ 7:14 am

[…] David Brooks is sloppy in his use of sociology: In this case, Mr. Brooks has taken his science from the work of Richard E. Nisbett, as described in his 2003 book The Geography of Thought: How Asians and Westerners Think Differently and Why, and in many papers, some of which are cited below. I was familiar with some of this work, which has linguistic aspects, and so I traced Brooks' assertions to their sources. And even I, a hardened Brooks-checker, was surprised to find how careless his account of the research is. The relation between Brooks' column and the facts inspired me to model my discussion after the Radio Yerevan jokes that arose in the Soviet Union as a way to mock the pathetically transparent spin of the Soviet media: […]