Decreasing definiteness

« previous post | next post »

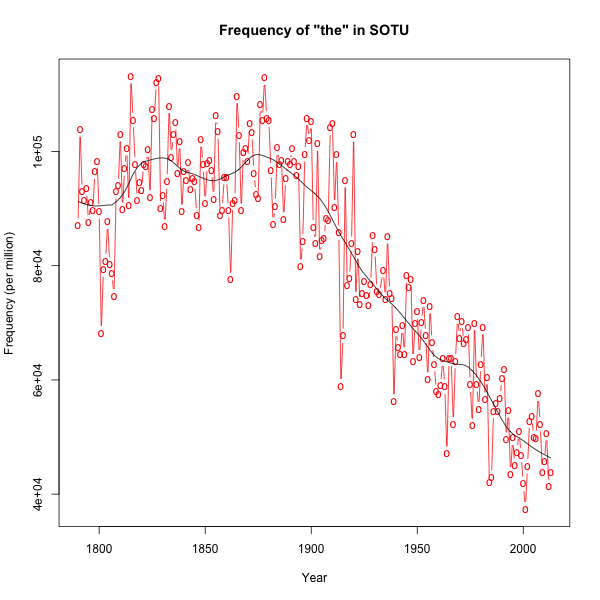

During the course of the 20th century, the frequency of the English definite article the decreased gradually and radically. I first noticed this effect about a year ago, in a post about the history of State of the Union addresses ("SOTU evolution", 1/26/2014), where I observed, in reference to the graph on the right, that

The average frequency of the in the most recent 10 SOTU addresses (2004-2013) was 47,458 per million words; in the first 10 addresses (1790-1799, all delivered as speeches to Congress) it was 93,201 per million words, almost double the frequency. And the decline during the 20th-century era of oral addresses seems to have been a gradual one.

The average frequency of the in the most recent 10 SOTU addresses (2004-2013) was 47,458 per million words; in the first 10 addresses (1790-1799, all delivered as speeches to Congress) it was 93,201 per million words, almost double the frequency. And the decline during the 20th-century era of oral addresses seems to have been a gradual one.

I speculated that

Maybe the style of speeches has been getting gradually less formal, and therefore gradually less like written style. Or maybe even formal styles have been changing.

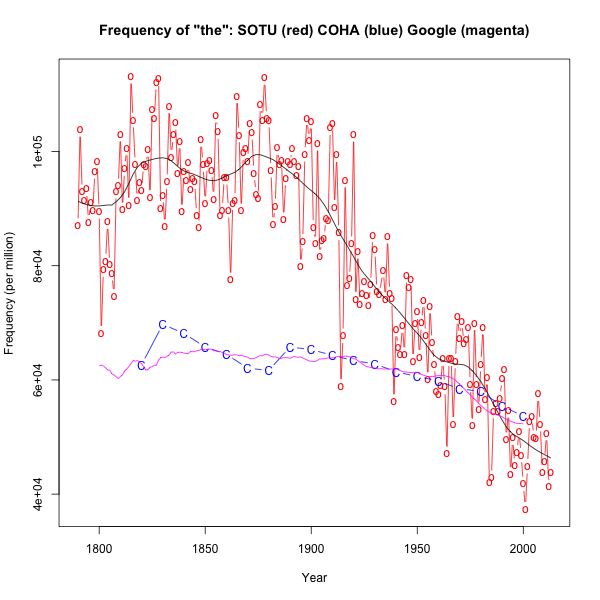

And I noted that a corresponding effect can be seen in two other sources, the BYU Corpus of Historical American English (COHA) and the Google Books N-Gram viewer (GNG), though it is considerably smaller in magnitude:

COHA and the Google Books data pretty much agree, which is reassuring; and they both suggest a slight decline in the frequency of the; but the change that they show is very modest compared to the change in SOTU frequencies. So I feel that the explanation for the SOTU change remains to be found.

COHA and the Google Books data pretty much agree, which is reassuring; and they both suggest a slight decline in the frequency of the; but the change that they show is very modest compared to the change in SOTU frequencies. So I feel that the explanation for the SOTU change remains to be found.

At that point, I turned my attention to other aspects of SOTU evolution. But a student paper recently reminded me of this issue.

In my undergraduate Introduction to Linguistics course, one of the assignments is a final project that asks the students to do some original analysis. Grading these reports (165 of them in the most recent batch) is always interesting and informative — this year, I learned about things like the rhetoric of professional wrestlers' "promos", or the differences between Dominican and Puerto Rican Spanish, or verbal auxiliaries and epenthetic vowels in Hindi film songs.

One of this year's projects, by He Chen, was "Analyzing the Differences in Journalism Style though the Percent Difference of Definite Articles and Indefinite Articles". Mr. Chen, a freshman in the Engineering School who gave me permission to use his name, created his own small historical corpus by selecting and downloading articles at random from the New York Times and Guardian indices, five articles per decade from 1860 to 2010. He then wrote programs to count articles, and to calculate confidence intervals for the difference in frequency between definite and indefinite articles. And despite the small size of his corpus, he found a statistically significant change in that difference, in the direction of decreasing definiteness. Overall, this was an impressive piece of work for a first-semester student in an introductory course.

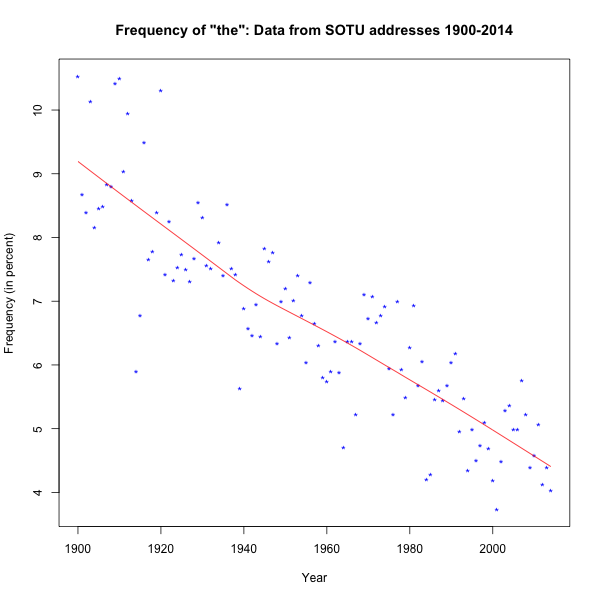

And it inspired me to look at the frequency of a/an as well as the, in various larger historical collections where the counts are easy to do, starting with the SOTU addresses. Focusing on changes since 1900, and plotting the counts in individual addresses as well as a lowess fit:

|

|

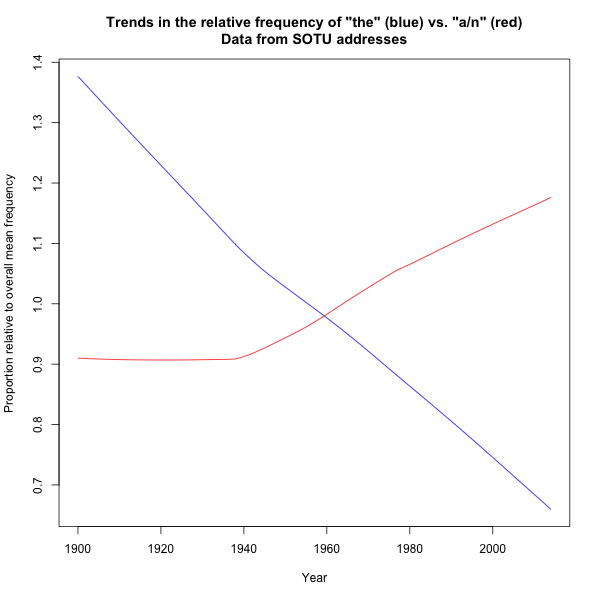

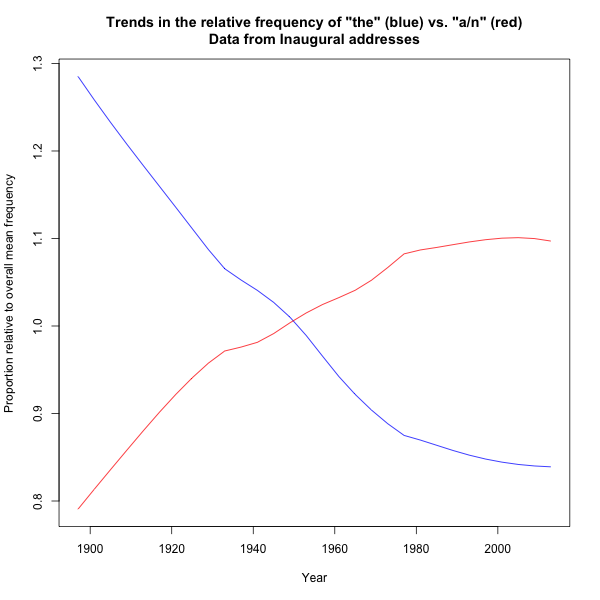

And scaling both the lowess trend lines in proportional terms relative to their average values in the plotted interval, we get

Again, the frequency of the has decreased by about half; the frequency of a/an has increased by about a third (though of course the overall frequency of a/an is much lower).

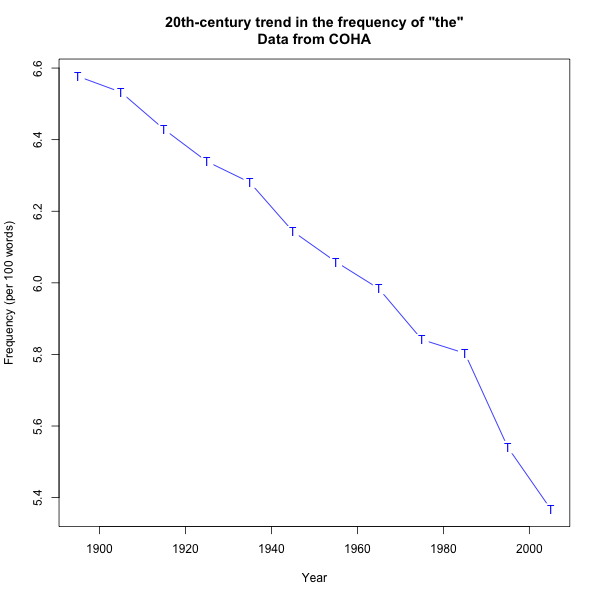

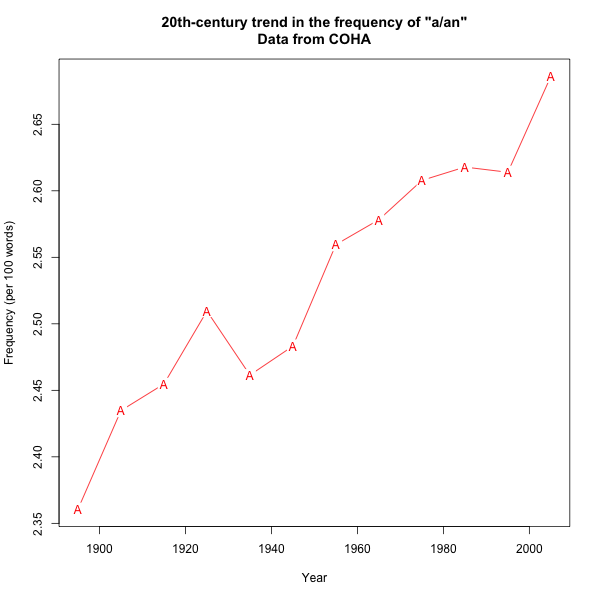

What if we look at the same frequencies in COHA, where there's enough data for us to use the raw values rather than the results of fitting a trend line?

|

|

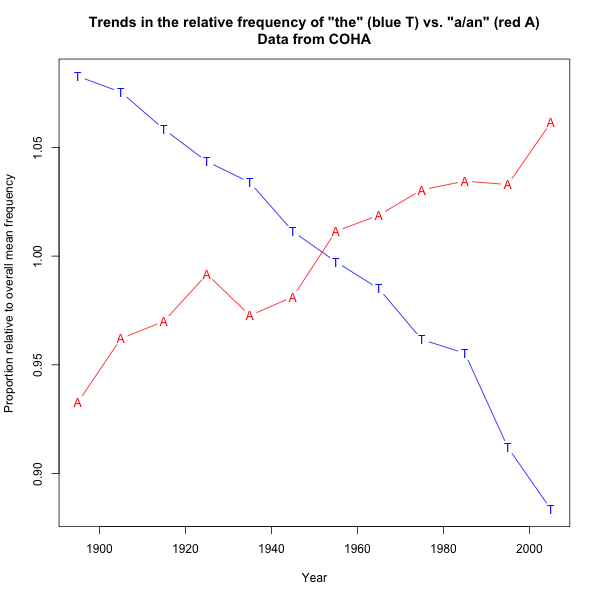

Again, in proportional terms, on the same plot:

Here the effects are much smaller — the decreases in frequency by about 22% in relative terms, from 6.6% to 5.4%, while a/an increases in frequency by about 14%, from 2.4% to 2.7%. Still, these words are common for these changes to be stylistically as well as statistically significant.

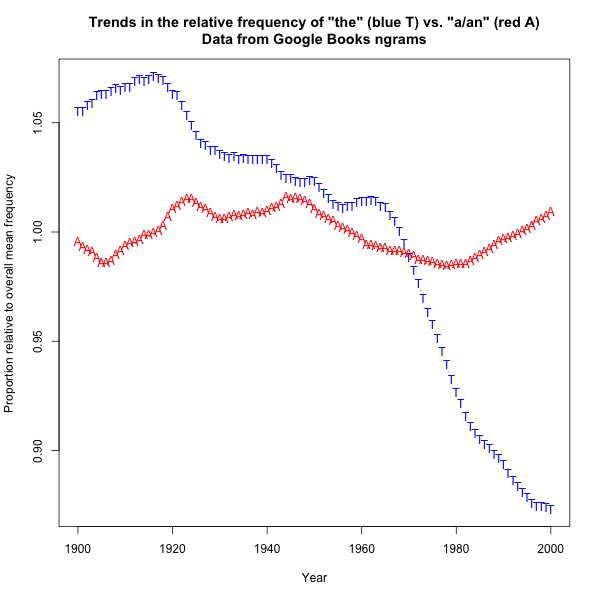

What about in the Google Books ngram index? Here are the analogous plots:

|

|

Here the changes in a/an, as well as being relatively small, are no longer monotonic. But the again falls by about 22% in relative terms, from 6.4% to 5.2%.

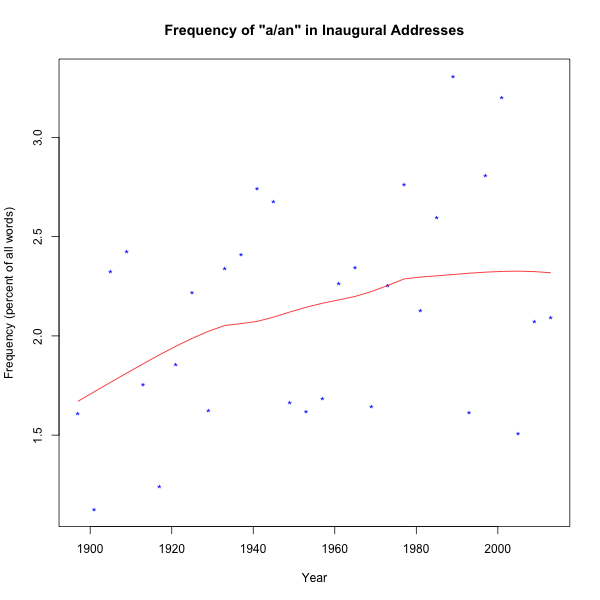

And to add one last source of evidence to this morning's Breakfast Experiment™, here are the results for (U.S. presidents') inaugural addresses, from 1897 to 2013:

|

|

In this dataset, the decreases in frequency by about 35% in relative terms, from about 8.0% to about 5.2%., while a/an increases by about 39%, from about 1.7% to about 2.3%.

So in all of the four data sources considered so far, the consistently declines in frequency over the course of the 20th century, monotonically and by a relatively large proportion. The behavior of a/an is less consistent, and in any case the changes are not large enough to suggest a simple trading relation between definite and indefinite reference.

What's the explanation for these changes? That's the really interesting question — but I've run out of time this morning, and this post is already far too long. So more on that later.

Update:

"Why definiteness is decreasing, part 1", 1/9/2015

"Why definiteness is decreasing, part 2", 1/10/2015

"Why definiteness is decreasing, part 3", 1/18/2015

kaleb said,

January 8, 2015 @ 7:39 am

interesting!

Anson said,

January 8, 2015 @ 7:56 am

I find these analyses fascinating. Lately I've been wondering about the use of "to be sure" to qualify an assertion. Here's an example from a recent Salon.com posting:

"According to Kristeller, an understanding of art as an autonomous sphere arose only in the eighteenth century, coincident with the rise of the new discipline of aesthetics.

"To be sure, there are also contrary voices. Perhaps the most incisive critic of the view…" [emphasis added]

It seems to me that this usage of the phrase has been cropping up more often recently. I've also noticed that John Oliver uses the phrase in this way quite a bit on his HBO show Last Week Tonight. If use of the phrase really is increasing, does it track the popularity of Last Week Tonight? If so, what other phrases might have experienced a similar "John Oliver Effect" in the past?

Victor Mair said,

January 8, 2015 @ 9:28 am

This is an elegant and interesting breakfast experiment (as they nearly all are).

Three points:

1. I find Mark's choice of blue vs. red color symbolism to be intriguing. If it were me, I'd probably switch them around.

2. It may not be a simple trading relationship between decreasing definiteness and increasing indefiniteness, but I sense that there is an overall correlation.

3. Since my college days until the present, I personally have experienced this change in my own writing and speech, so that nowadays I often pause before deciding whether to insert "the" before a noun, whereas I've been using "a / an" with less deliberation than heretofore.

Adrian said,

January 8, 2015 @ 9:32 am

Reading some SOTU statements from the 1870s, two things occur to me. One is that we use bare nouns more often these days. This could be analysed by comparing collocations such as "(the) relations", "(the) regions" and "(the) correspondence" between then and now. Another is that leaders used (perhaps) to be more impersonal. I see, for example "the country" where today I'd expect "our country" (or some other formulation such as "this great country of ours"). Again, this can be analysed. A third matter to analyse would be the ratio of nouns to verbs.

Dan Shore said,

January 8, 2015 @ 9:34 am

One ready-made explanation for these sorts of changes in article usage: urbanization, or at least a general increase in the percentage of people who live in relatively large population centers. (Hugh Craig has written about this with regard to people living in 16th- and 17th-c England.)

In simple terms, when you live in small parish, you talk about "the priest" or "the butcher." In a larger town or city you talk instead about running into "a priest" – one out of many in the town. In describing your day you're more likely to report stipping by "a grocery store" than "the grocery store" if you live in a place where there are multiple grocery stores. More people living in areas of dense populations where common nouns for social reference points have multiple referents = an increase in definite and a decrease in indefinite articles.

This is *an* hypothesis, anyway.

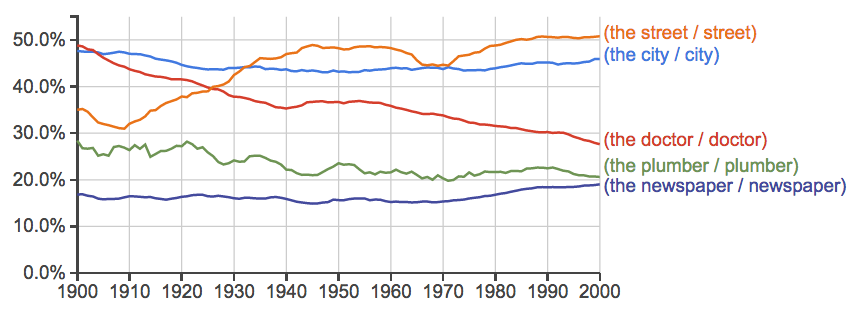

[(myl) Luckily, this hypothesis is easily subject to various tests, and it seems to come up short. For instance, here's a plot showing what percentage of instances of "priest", "butcher", and "grocery store" are preceded by "the", in the Google Books ngram index for American English books published between 1900 and 2000:

You may well be right about changes in how people talked — though that remains to be seen — but you seem to be wrong about how they wrote, at least with respect to these three cases. The arthrousness of "priest" and "butcher" decreases (non-monotonically) by about 13% (relative) over the course of the century, while that of "grocery store" increases by about 220%. Trying a few other nominal heads gives similar results:

]

KevinM said,

January 8, 2015 @ 9:49 am

@Anson. I associate "to be sure" with journalism. There's something called the "to be sure paragraph" that every story is supposed to have. (That is, the qualifying paragraph that renders the story non-falsifiable.)

GeorgeW said,

January 8, 2015 @ 10:00 am

Without a great deal of thought, I think I find it easier to drop 'the' than 'a/an.' In addition, sometimes 'a/an' can be substituted for 'the.' Example (from comment above):

According to Kristeller, an/the/_ understanding of/_ art as an/*the autonomous sphere arose only in the/*an eighteenth century, coincident with the/a rise of the/a new discipline of aesthetics.

Maybe, more generally 'a/an' can give the speaker/writer a little more wiggle room or deniability than the more specific 'the.'

Andrew (not the same one) said,

January 8, 2015 @ 10:11 am

One factor may be the tendency of various institutions to drop 'The' from their names, or at least the popularly used versions thereof; for instance, the recently formed unified police service for Scotland is not called The Scottish Police Service, but Police Scotland. I find that use of such names often produces sentences which feel a bit ungrammatical, but the institutions tend to insist on it. (And indeed, people who say 'The Language Log' are liable to be corrected.)

Victor Mair said,

January 8, 2015 @ 10:48 am

On the other hand, it is still The Ohio State University, and I think that you're also supposed to say The Johns Hopkins University.

cameron said,

January 8, 2015 @ 11:03 am

@Victor Mair:

Broadcasts of NFL games often feature photomontages of players stating their names and where they played college ball. I've noticed that former Ohio State players often strongly stress the definite article when naming that school.

kaleb said,

January 8, 2015 @ 11:10 am

@Dan Shore, you hit the nail..

Tim Morris said,

January 8, 2015 @ 12:11 pm

Very interesting data and comments. I wonder if conscious de-gendering of English is a factor. Instead of phrases like "the man who," "the woman who," one might choose "people who" (conveniently enabling the non-gendered pronoun "they").

david said,

January 8, 2015 @ 12:21 pm

http://thefacebook.com still works, though not many people remember it started that way

J. W. Brewer said,

January 8, 2015 @ 12:29 pm

One way of testing Dan Shore's hypothesis is to use the google books n-gram viewer to compare the frequency of, let's say, "went to the grocery store" vs. "went to a grocery store" over time. SPOILER ALERT: the trend over the course of the 20th century, especially since c. 1970, turns out to be the opposite of what the hypothesis would predict.

Now, that's only one datapoint and maybe it's because the "the" is part of a fixed phrase (for example, the AmEng "in the hospital" contrasts with the BrEng "in hospital," and does not on either side of the Atlantic depend on whether there is more than one hospital in the relevant geographical area). But there are a lot of fixed phrases like that. For example, I would say "I'm going to be late for work next Tuesday because I have to take my kids to the dentist" even though there are lots of pediatric dentists in the area where we live and the person I am speaking to may have no idea which one I'm talking about (which, to be fair, is not really salient to the point being communicated, since it's not as though taking them to Dr. A would be a better excuse for being late for work than taking them to Dr. B).

Neal Goldfarb said,

January 8, 2015 @ 12:49 pm

I agree that Dan Shore's hypothesis seems promising, but I think that focusing on urbanization in particular is too narrow and doesn't fully capture the generalization that I think underlies his idea.

The grammatical features definiteness and indefiniteness are markers of whether the the noun they go with refers to something that the speaker/writer expects the hearer/reader to be familiar with, or at least be able to identify. If the referent is assumed to be known or identifiable, the definite article is used, and if not, the indefinite article is used.

The familiarity or identifiability can be result from a variety of factors including the linguistic context (the referent has already been mentioned in the discourse), the physical context of the conversation (the referent is right there in front of the listener's eyes), or—and this is the important part—common knowledge. For instance, when we talk about the U.S. government we use the, even if the government hasn't previously been mentioned in the conversation and isn't in the room, because it's common knowledge that the United States has a government.

So what this suggests is that the decrease in the use of the and increases in the use of a/an is evidence that people are increasingly talking about things that they assume are not familiar or identifiable to their listeners. Or stated otherwise, they are increasingly introducing new entities into the discourse. One possible explanation for this would be that the universe of things that people talk about is expanding. To use Dan's examples, a village may have only one priest, one butcher, and one grocery store, but a big city will have many of each.

Urbanization is only one of many factors that can cause the universe of discussion topics to expand. Others would presumably include industrialization (the invention of new kinds of objects and methods of production), improved transportation and communication (people become exposed to new things, new ideas, new people), increased literacy (reading expands your world).

Generalizing from this, we could say that the increase in the number of things to talk about results from (or at least corresponds to) culture becoming more complex, and society (and societies) becoming more interconnected.

Therefore, the hypothesis is that changes in the relative use of definite and indefinite articles is a reflection of the ever-increasing complexification and connectedness of human culture and society.

Is this merely a just-so story? Beats me. But if anyone writes a paper exploring the issue, please send me a copy.

richard said,

January 8, 2015 @ 1:25 pm

Hmm, it occurs to me that there may be different mechanisms at work in different types of writing. I know in my academic discipline (ethnomusicology) and related fields (anthropology, sociology, historical musicology…), there was a determined shift from grand narrative starting in the 1980s and 1990s. One feature of this shift was a desire to show multiplicity of meaning and experience, and an effort to avoid suggesting that only one approach was valid. To do this, writers pluralized core concepts (music–>musics, culture–>cultures, world–>worlds), and used phrases using "one" or "a/an" instead of "the." Scholars using "the" in a context in which there could be disagreement or multiple interpretations (which quickly became any context…) were sometimes attacked for anything from premature synthesis to neocolonialism. And this shift still characterizes much of the writing in these disciplines.

But I doubt that relationship obtains in other kinds of writing.

Joe said,

January 8, 2015 @ 1:57 pm

While Neal Goldfarb's "complexification" or Dan Shore's urbanization theories sound very interesting, the reason may simply be just a shift in styles, as Mark initially suggests. If we follow the theories thorugh, we'd probably see the uptick of "a/an" as more consistent or directly proportional with "the" decreases (that is, a substitution of articles as Neal describes: "If the referent is assumed to be known or identifiable, the definite article is used, and if not, the indefinite article is used").

Could it be that "the" is just superfluous in many cases and we're just seeing a trend where it is just dropped? An example in one of George Washington's SOTU addresses: "…those who are intrusted with the public administration…" could likely be renderred nowadays without the "the".

BZ said,

January 8, 2015 @ 2:16 pm

Re urbanization / context change thing:

I think these things are much less quick to change if at all. After all, people are still "in the hospital" or "on the bus" no matter how many hospitals or buses exist in the speakers vicinity. It's only when the location/identity of the entity being talked about is relevant that this type of construction begins to break down. In this case, one can use either the brand name or address (or both) to disambiguate things. The former can potentially lead to loss of article depending on whether the name has one and if so, how readily it can be dropped. I cannot imagine how an indefinite article can be inserted during this type of change. No one would say "I bought this at a supermarket" (groceries and butchers seem to be going away in general). Either you'd say "the supermarket" or its name. I wouldn't worry about location because chain supermarkets typically have the same selection of items at similar prices.

Re: "to be sure", I'm pretty sure I learned of this construction by reading it rather than hearing it, and in classical fiction (which was what I was mostly reading at the time), which lead me to believe that it was somewhat old-fashioned. Sure enough, the Google n-gram viewer shows a consistent decline in use since the 1940s.

Bloix said,

January 8, 2015 @ 2:22 pm

@Dan Shore – really? Did you ever ask your spouse, "Did you go to a grocery store?" Has anyone ever said to you, "My dad's in a hospital"? Did a colleague ever say, "Sorry I'm late, I had to take my kid to a doctor"? Do you ever say, "I'm on my way, but first I have to stop at a bank"?

BZ said,

January 8, 2015 @ 2:43 pm

@Bloix,

I lived and worked in Morristown, NJ for 5 years. My place of work was downtown which was dominated by banks (5 of them, I think). During lunch, I would often walk along thee square and enter the first bank that had no line inside or at the ATM, depending on what I needed at the time. I can almost imagine saying your final sentence because I did not know which bank I would stop at until I was there. Once I was there or after I left, it would become "the bank".

Coby Lubliner said,

January 8, 2015 @ 2:54 pm

If I remember correctly, in the 1980s Internet was used anarthrously alongside Bitnet and ARPAnet, and it took me a while to get used to saying "the Internet"; that may, however, have been a peculiarity of my environment.

I also remember Ronald Reagan's fondness for saying "the Congress," though I don't see any blip on the SOTU chart that might reflect that.

J. W. Brewer said,

January 8, 2015 @ 3:08 pm

I suspect the overall slight (outside of SOTU context) but noticeable shift over time in the a/an v. the ratio is probably the aggregate result of a lot of smaller and more specific phenomena, not all of which point in the same direction. Maybe there are twelve sorts of contexts where there's been a shift from definite to indefinite and eight sorts of contexts where there's been a shift the other way (plus a bunch where there's been no shift at all) and myl's graphs show how all of those net out without there being any single overall grand explanation. And of course as noted above in various ways there's also the wild card of shifts between arthrous and anarthrous constructions, which influences the trendlines on myl's graphs without being shown as a trendline of its own.

Nick Barr said,

January 8, 2015 @ 3:31 pm

I wonder if part of the decline of "the" is due to the way we talk about feelings and states — "I haven't had the pleasure," "She has the suspicion that," "I have the impression" etc. all feel old-timey to me. We seem to prefer adjectives today: "I'm pleased," "I suspect," etc.

Definitely not a sufficient explanation but maybe a part of the puzzle.

Also doesn't explain why "a/an" would be eating away at "the."

Neal Goldfarb said,

January 8, 2015 @ 3:58 pm

@ J.W. Brewer:

I'm sure that's right. I've come over time to the view that the only true linguistic universal is "It's more complicated than you think."

Regarding the grocery store-type phrases: I agree that these don't bear out the complexification hypothesis, but neither do they t rule it out as one factor among many.

More broadly, it's easy to come up with examples that support one view or another, but that doesn't do much to answer the question "Why?"

Victor Mair said,

January 8, 2015 @ 3:58 pm

Very interesting real time datum.

I was just writing to my colleagues and typed this sentence:

"It seems to me that XXX would be a good nominee for

thea Presidential Professorship."I had actually just finished typing "the", then instantly backspaced over it and entered "a", without giving it too much thought.

I've probably done something similar thousands of times in recent years.

David Morris said,

January 8, 2015 @ 4:06 pm

Other words which work similarly in sentences to 'the' are 'this/that/these/those'. A decline in talking about, for example, 'the nation' might be matched by a rise in talking about 'this nation'. This is obviously not the complete explanation, but may be an additional factor. My intuition is that there isn't likely to be *one* explanation, but rather a range of inter-related factors.

Rubrick said,

January 8, 2015 @ 5:11 pm

This trend is unquestionably a sign that we are nearing an End Times.

Victor Mair said,

January 8, 2015 @ 5:30 pm

@Rubrick

"we are nearing an End Times"

Which one?

Because we are unwilling to commit ourselves to anything specific?

Minivet said,

January 8, 2015 @ 5:49 pm

I'm sure there are a lot of aspects to this, but I think part of the story is how we slam nouns together much more readily today.

I went through Obama's 2014 SOTU and found at least 123 combinations (I skipped some duplicates which in retrospect I shouldn't have): graduation rate, farm exports, housing market, breakthrough year, trade partnerships, budget cuts, intelligence community, etc., etc. Then I went through Wilson's 1914 address, which contains just about exactly 1/3 fewer words, and found only 12, many more of them set phrases and with more repetitions: merchant marine, water power, coast line, business sense, reserve army.

Also, I did a search for "of the" in both speeches to see how much that has decreased. from 58 instances in 1914 (1.3% of the total words, counting "of the" as one word), versus 28 in 2014 (0.4%).

Of course, many noun combinations today would only be linked by "of", not "of the", in the past. Examples in the Wilson speech: "program of legislation", "regulation of business", "processes of production", "lines of trade".

Interestingly, "of" dropped by more than "the" between this pair of speeches, from 4.8% to 2.3%. Something else to examine more closely?

Anson said,

January 8, 2015 @ 5:50 pm

@KevinM I understand the use of the phrase to indicate journalistic fairness. It just seems to me that the use of "to be sure" in that sense has been increasing recently. It could just be that I'm more attuned to it lately. Having said that…

@BZ the Google n-gram viewer does indeed show a steady decline in the use of "to be sure" since the forties, but it also shows a definite uptick since around 2000. I wonder what prompted that change? The increase started before Last Week Tonight did so my John Oliver Effect hypothesis doesn't seem valid.

More on-topic, I wonder how much the decline of the definitive is purely an American English phenomenon. For example, British English regularly says "So-and-so went to hospital" while American English usually says "So-and-so went to the hospital." There are probably other examples.

Pflaumbaum said,

January 8, 2015 @ 6:32 pm

Hypotheses like Dan Shore's 'urbanisation/more butchers' one seem plausible at first glance, but there are a lot of assumptions involved.

For instance, does a reduction in grammaticalised definiteness necessarily mean that the reference system of the language is overall becoming less definite to that degree (especially that the increase in a/an seems less pronounced)? Or might definiteness be being marked in other ways?

Russian for instance has no article but variation in word order can resolve ambiguities, and (though I'm only a beginner in the language) my sense is that choice of verbal aspect can influence the definiteness of noun phrases too.

Also, does a grammatical change like this require an explanation in terms of real-world referents? So Greek gained a definite article while Latin retained the article-less IE system, but then the Romance languages developed articles… do we really want to posit a series of societal changes that led to a need for more definiteness in different times and places (perhaps along the lines of urbanisation)?

Isn't something internal to the language – like the aggregate influence of the first-language nominal systems of a global non-native English-speaking population – just as likely?

(It occurs to me that I have no real idea why I chose a before global in the sentence above…)

Alicia said,

January 8, 2015 @ 6:37 pm

Regarding the urbanization etc thesis. I side with the people who say that they will never tell their spouse that they are going to "a" store. However many stores there are, most households still do most of their shopping at a short list of defaults. If I were wanting to make clear to a member of my household that I intended to buy food somewhere other than our local Shoppers Food Warehouse, I would probably say something like "I'll try to stop somewhere on the way home."

However. I can easily imagine increased density, population mixing, etc causing some definite articles changing to possessives. Where one would previously have said "As I said to The Preacher…" one might now say "As I was saying to our preacher." Or "my kid's school." Doesn't explain the rise of a/an, but then that hasn't gone up as much as the has gone down.

Matt S said,

January 8, 2015 @ 6:38 pm

Kaleb, you didn't finish the aphorism.

Did he hit the nail on its head, or on the head?

hector said,

January 8, 2015 @ 7:43 pm

I'm just throwing this out as a suggestion: nineteenth-century writing tends to be much more verbose than the more journalistic style that started developing between the two world wars. Sentences tend to be shorter and punchier now. Perhaps the rhythm of modern writing produces less "the's" and more "a/n's"?

John Walden said,

January 9, 2015 @ 4:08 am

I don't think there's one answer to this either.

Do we tend to generalise with plurals more?

"The African elephant has bigger ears"

has a whiff of the archaic about it; I think most people would opt for

"African elephants have bigger ears"

and I doubt if as many people say "The French" as they used to. "French people" seems less Edwardian.

Another tiny contribution might be dropping "The" from country names like Lebanon, Gambia, Ivory Coast. In fact I hear "I'm going back to UK" from time to time.

Lane said,

January 9, 2015 @ 6:24 am

My first hunch was Neal Goldfarb's. My version: in the past, education was the same thing for most people, so nonfiction books would refer to presumed common knowledge like "The historian Thucydides" or "The Roman philosopher Seneca". Today, we have so much more specialized education that book-writers know they may be writing for an electrical engineer, and so write "Thucydides, a Greek historian" or "Seneca, a Roman philosopher".

But Google n-gram is thwarting me – it doesn't find any results for "Seneca a Roman philosopher", because it probably is looking for the comma that would normally appear in "Seneca, a Roman philosopher." (Google BOOKS does turn up 1,210 mentions of "Seneca, a Roman Philospher.") But since commas delineate search terms in the N-Gram Viewer, I can't figure out how to search for the comma'd version there. Maybe someone else can figure it out and give it a spin. How could we search for the contrasting frequencies of

[Name], a [common noun]

and

The [common noun] [Name]

?

Missing “The”: Is There an Upside to Ambiguity? | The Misfortune Of Knowing said,

January 9, 2015 @ 7:20 am

[…] as much as it used to be. I wouldn’t have noticed its absence without those fine folks over at Language Log, who found that “[d]uring the course of the 20th century, the frequency of the English definite […]

Tam said,

January 9, 2015 @ 9:49 am

I've been wondering about this myself after having noticed recently that you can make yourself sound older/out of touch by introducing spurious definite articles (try "the Facebook" or, as I heard on tv recently, "the identity theft").

chris said,

January 9, 2015 @ 10:57 pm

What's the explanation for these changes? That's the really interesting question

Well, it is *a* really interesting question…

Maybe an explanation (not necessarily the only one) is that people are becoming more aware of the complexity of life and things having multiple causes? Which sounds somehow different than saying that *the* people are doing the same thing.

Although not as different as "The people are revolting" and "People are revolting", but that's because of ambiguity elsewhere in the sentence.

P.S. I'm somewhat skeptical of Dan Shore's idea upthread, because it seems to me that I'm still likely to talk about going to "the" grocery store or bank even when I have several to choose from; but John Walden seems to me to be on to something.

Andrew said,

January 10, 2015 @ 12:34 pm

I notice that recent advertising tends to avoid using the definite article with product or service names. You can also see this in Apple keynotes where it's now always iSomething and never the iSomething. That might be an interesting corpus to compare.

Ellie Kesselman said,

January 16, 2015 @ 6:56 am

I was too lazy to read the entire post, but I did read all the comments! Usage frequency changes of "the" versus "a/an" might be due to increasing ignorance about what is, or is not, a proper noun. Also, a sample based exclusively on President Obama's speeches is not sufficient. That was dealt with quite thoroughly by student He Chen's commendable work… yes, I did read some of the post.

In case you missed it, The Guardian UK devoted an entire article to these findings, see "Use of definite article shows ‘radical decline’ in last century, research shows"

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/jan/15/definite-article-radical-decline-last-century-research (Academic’s analysis of American English usage shows striking fall, suggesting ‘trend towards greater informality in writing’)

Language Log garners attention from global media. Well done!