Homa Obama

« previous post | next post »

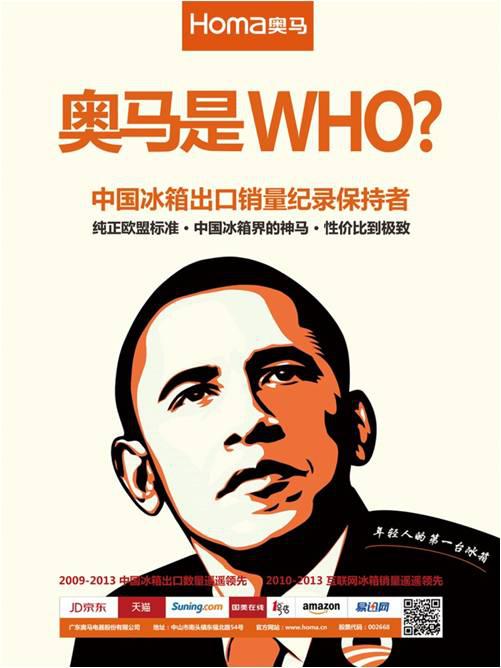

Tom Mazanec sent in the following ad that he saw in a Guangzhou (China) apartment complex:

I'll transcribe and translate all the main parts of the ad:

Àomǎ shì WHO?

奥马是WHO?

("Who is Homa?")

Never mind that Àomǎ 奥马 is often used as a sinographic transcription for "Omar", "Omagh" (place name in Northern Ireland), "Alma" (place name in Malaysia), etc.; here it is meant to transcribe the name of the company, viz., Homa. The character ào 奥 means "abstruse; obscure; profound; mysterious", etc. and mǎ 马 means "horse", but in this instance their primary role is for transcriptional purposes.

So far as I know, the name of this company has nothing to do with the ancient, sacred, presumably entheogenic, ritual drink of the Indo-Iranians known as soma or haoma.

Zhōngguó bīngxiāng chūkǒu xiāoliàng jìlù bǎochí zhě

中国冰箱出口销量纪录保持者

("Chinese refrigerator export sales record holder")

chúnzhèng Ōuméng biāozhǔn

纯正欧盟标准

("Genuine EU standards")

Zhōngguó bīngxiāng jiè de shénmǎ

中国冰箱界的神马

("Divine horse / Pegasus of the Chinese refrigerator industry")

xìngjiàbǐ dào jízhì

性价比到极致

("Extreme performance to cost ratio")

The main joke is the play on the Chinese versions of the names of Homa (Àomǎ 奥马) and Obama (Àobāmǎ 奥巴马), with references to the famous "Hope" poster from 2008. There's also the corny play on the graph mǎ 马 in the smaller slogan — Zhōngguó bīngxiāng jiè de shénmǎ 中国冰箱界的神马 ("Divine horse / Pegasus of the Chinese refrigerator industry") — which is also part of the names Àomǎ 奥马 and Àobāmǎ 奥巴马.

Why the slogan uses the English "who" instead of shuí 谁 is a bit more puzzling. What were they trying to achieve by inserting this English word? To catch people's attention? To seem trendy? Cool? In some of their other ads, they stick a yellow post-it on one of their refrigerators with these three English words: "It is cool." In any case, it's clear that the ad expects its readers to know enough English vocabulary to get something from "who".

There's a follow-up to this ad on Homa's website, with a banner saying Àomǎ bùshì Àobāmǎ 奥马不是奥巴马 ("Homa isn't Obama"):

My first impression was that this was a cheap extension of an already forced comparison between Àomǎ 奥马 and Àobāmǎ 奥巴马. But looking at the two ads together once more, I noticed some subtleties that convey a clever message.

The first ad says "Who is Homa?" with an obvious — though unspoken — visual allusion to a dreamily hopeful Obama looking upward to the future. The second ad says "Homa isn't Obama", with the President turned away, hands in his pockets, and head facing downward.

The three phrases in small characters under the main slogan of the second ad are the same as in the first ad. As for the characters in the circle, they say, "13% shàng bànnián chūkǒu xiāoliàng dì yī 13% 上半年出口销量第一 ("13% export sales in the first half number one"). I'm not sure whether that is supposed to mean 13% increase in sales during the first half of this year, or 13% of total sales in China / the world, or something else, and I also don't know why the arrow is pointing at Obama? In any event, they want you to know that Homa is "number one", a frequent theme in their advertising.

This is not the first time that a Chinese company has capitalized on the fame of President Obama to push its products ("Real fake"), and I'm sure that it won't be the last.

GeorgeW said,

September 22, 2014 @ 3:00 pm

Out of curiosity, how is Obama viewed in China? (if there is any common view) That might make these ads more understandable to us (Americans, westerners).

carl said,

September 22, 2014 @ 3:05 pm

you mean "shéi," not "shuí."

Yuanfei said,

September 22, 2014 @ 4:02 pm

Perhaps "who" serves as a pun of the "ho" part of "Homa" since 奧馬 is not spelled as Aoma in its English name of the brand. Homa also reminds me of the epic poet Homer whose Chinese name is 荷馬. And 荷 is pronounced the same as 何, which means "which" "what," and if paired with "人" 何人 means "who?"

Victor Mair said,

September 22, 2014 @ 5:02 pm

@carl

No, I meant what I wrote.

Having learned most of my Mandarin in Taiwan 40 years ago, I always pronounce 誰 as shéi, and would feel very awkward forcing myself to say shuí.

誰

http://dict.revised.moe.edu.tw/cgi-bin/newDict/dict.sh?idx=dict.idx&cond=%BD%D6&pieceLen=50&fld=1&cat=&imgFont=1

http://www.zdic.net/z/24/js/8AB0.htm

On the other hand, most reference works from the Mainland give preference to the pronunciation shuí.

谁

http://baike.baidu.com/subview/356606/5096145.htm

http://www.zdic.net/z/24/js/8C01.htm

http://www.iciba.com/%E8%B0%81

http://www.nciku.com/search/all/%E8%B0%81

Yet, even the authoritative Xīnhuá zìdiǎn 新华字典 and Xiàndài Hànyǔ cídiǎn 现代汉语词典 give both shéi and shuí as variants for 谁, though showing a preference for the latter.

Guy said,

September 23, 2014 @ 6:27 am

"Aoma shi who?" is an extremely awkward headline to say the least.

At its worst, it's probably teaching a bunch of Asian kids that "Obama is who?" is correct English.

Also, "13% 上半年出口销量第一" means in the first half of the year they were the leading exporter with 13% market share. I don't think it makes any sense unless you are used to reading nonsensical Chinese ad copy. I guess its like British news headlines, makes no sense to non Brits or non-native English speakers.

Michael Watts said,

September 23, 2014 @ 6:51 am

Well, anecdotally, shéi is beating shuí in Shanghai by some margin approaching 100 percentage points, as far as I can tell.

Less anecdotally — as viewed through pleco for android, the xiandai hanyu guifan cidian (I don't know if this is the same as the xiandai hanyu cidian you mention) gives both shéi and shuí, but has a very marked preference for shéi:

谁 shéi – has four definitions listed, with examples, and a note:

注意 又读shuí。在古诗文中一般读shuí。 [N.B. Also pronounced shuí. In ancient literature, normally pronounced shuí.]

Whereas the entirety of the entry for

谁 shuí – is…

"谁(shéi)"的又音。见谁的提示。 [The additional pronunciation of “谁(shéi)". See the note for shéi.] [In the app, the 谁 of 见谁的提示 is a link to the entry for 谁shéi.]

Yiyi Luo said,

September 23, 2014 @ 9:45 am

Another layer of meaning in the phrase "冰箱界的神马"–the phrase 神马 not only draws on its literal meaning, "divine horse," but also conveys a sense of humor. 神马 nowadays is used (especially online) as a fashionable alternative to 什么 (“what”). For example, instead of saying 今晚吃什么,one says 今晚吃神马. So the phrase not only brags about its quality, but also is meant to be funny.

Victor Mair said,

September 23, 2014 @ 10:24 am

@Michael Watts

The Xiàndài Hànyǔ guīfàn cídiǎn you mention is definitely NOT the same as the Xiàndài Hànyǔ cídiǎn that I cited. Although the former arrogates to itself the designation "standard" (guīfàn), it is the latter that is the de facto official one volume dictionary of MSM (Modern Standard Mandarin), inasmuch as it is compiled by the Institute of Linguistics of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. (There have actually been court cases in China, brought by high officials of CASS, over the misleading name of the former dictionary.) I do not have in my office a copy of the latest edition of the Xiàndài Hànyǔ cídiǎn, but I will check a more recent edition when I go home this evening, unless someone gets to it sooner.

Anecdotal Shanghai evidence is not a good test for MSM usage.

You may not be aware, but ABC-Wenlin is a main source for Pleco (I am the founding editor of the ABC Chinese dictionary series). The latest print edition of our dictionary is the ABC English-Chinese Chinese-English Dictionary. The main entry for this term is on p. 898a, where the pronunciation shuí is given and the 6-line entry ends with "See also shéi." The 4-line entry for shéi is on p. 874a; it begins with the notation that this is the "coll[oquial] pronunciation" and ends with "See shuí."

But, oh my goodness, none of this is of any great importance. Some people say shuí and some people, including me, say shéi. Just because I pronounce that morpheme as shéi, I don't think that I have a right to impose that pronunciation on others who pronounce it as shuí. Ditto for 李白 and 白居易, which I — and millions of others — pronounce as Lǐ Bó and Bó Jūyì, and have been doing so for half a century or more. We do not appreciate being told that we are wrong, and that these two names should be pronounced as Lǐ Bái and Bái Jūyì.

Victor Mair said,

September 23, 2014 @ 7:15 pm

Today in my Classical Chinese class, of the six native (PRC) speakers of MSM, four of the students (from different parts of China) pronounced 谁 as shéi. One student, from Shanghai, pronounced it as shuí. When I asked him why he pronounced it that way, he told me that's the way he had always pronounced the character and that he thought it was the right way.

The most interesting case, however, was the last student, a girl from Chaozhou who made it sound like this: shueí. I requested that she repeat herself several times, and it kept coming out as shuéi. That sounded very peculiar to me, so I asked her how she acquired such an unusual pronunciation, which sounded like a combination of shuí and shéi. The answer she gave me was incredibly revealing and almost bowled me over.

She said, "Well, I always used to say 'shéi', since that's the way I learned it from my parents, but then when I went to Beijing, my teachers from Beijing Normal University insisted that we students pronounce it as 'shuí'." !!!!

Language teachers from Beijing Normal University are famous for being sticklers when it comes to the "correct" pronunciation. Clearly, they maintained that "shuí" was correct and "shéi" was incorrect. My student had probably done everything possible to meet their demands, but now, no longer under their tutelage, was slipping back to her old, natural pronunciation, "shéi", yet was still retaining some of the PRC standard pronunciation forced upon her by the Beijing Normal University teachers, viz., "shuí".

Michael Watts said,

September 23, 2014 @ 9:35 pm

I don't understand the difference between shui and your form shuei. Is "shuei" supposed to be two syllables? The -ui suffix already indicates the sound 'wei'.

Akito said,

September 23, 2014 @ 10:27 pm

In my understanding, Pinyin writes the phonemic sequence /wəj/ as wei if it is not preceded by an initial, and as ui if it is. The latter doesn't mean that the nuclear vowel /ə/ is completely absent and in fact is very much present in third and fourth tones (and sometimes in other tones). Shuei is orthographically nonstandard but just emphasizes this fact. It doesn't mean there's an extra syllable.

Victor Mair said,

September 23, 2014 @ 11:52 pm

I just checked the 2002 edition of the Xiàndài Hànyǔ cídiǎn (there surely must be later editions, but that's the most recent one that I can find in my study at home). On p. 1118ab, it devotes 17 lines to defining the word shéi and giving examples of its usage; this is followed by five disyllabic entries that include the initial syllable. Right after the pronunciation shéi, it has this note: yòu yīn shuí 又音 shuí ("also pronounced shuí"). On p. 1182a, the same word is given the pronunciation shuí, after which comes this note: '谁' shéi 的又音 ("a variant pronunciation of '谁' shéi"). There are no definitions or illustrative sentences. For these the reader must go to shéi 谁. In this edition of Xiàndài Hànyǔ cídiǎn, the two pronunciations are given equal standing, with shéi having all the definitions and example sentences because it comes first in the alphabetical order.

As for the odd pronunciation of the Chaozhou student, which I indicated with the nonstandard spelling shueí, Akito understands correctly. It is not meant to be two syllables. If I could have done a small, superscript letter, I would have raised the "u" to indicate that there was just the hint of a "w" sound. All the other students either very clearly said shéi or shuí, but the Chaozhou student said something in between those two pronunciations. It was basically shéi, but with slight "w" rounding before the "éi" part of the syllable. As I mentioned in the note above (http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=14740#comment-1389957), the shape of the syllable that she uttered was so uncanny that I had her repeat it several times, and each time it came out "shueí", where the "u" was only minimally present.

L said,

September 24, 2014 @ 12:03 pm

"Pegasus of the Chinese refrigerator industry" is a phrase I did not expect to ever read.

Brian said,

September 27, 2014 @ 1:44 am

Not to belabor an already tired point, but I'd be curious to hear native opinions on this shei-vs.-shui question. I had the impression that shei was the usual pronunciation in everyday life, and that shui sounds bookish or pretentious. I believe I acquired this impression while at university in Beijing. But it would be interesting to know whether people have ideas about the different readings, beyond "right" and "wrong."

(And, irrelevantly, how did an American like me come to write the phrase "at university"?)

William Locke said,

September 27, 2014 @ 9:19 pm

At college in the US, I was exclusively taught the "shei" pronunciation by my Beijing-educated teacher (I'm not clear on whether she was native to Beijing–she had also been living in the United States for the last 20+ years). It wasn't until I went to Kaifeng, Henan in China that I encountered the "shui" pronunciation, and it confused me terribly at first. This was compounded by the fact that I was almost certain the lady who asked me "ni shi shui" (Who are you?) had moments earlier asked me if I wanted a cup of "shei" (water–MSM "shui"). This might have been a trick of my own reeling, overstimulated ears and brain after barely a week in China.