Not marble nor the gilded monuments

« previous post | next post »

Opinions were strikingly divided about Obama's inaugural speech, and not necessarily along ideological lines. George Will called it lyrical and Pat Buchanan called it "the work of a mature and serious man"; but in National Review, Yuval Levin said that within a few weeks not a line of it would be remembered, and Rich Lowry spoke of "overwrought clichés and poor writing." At the New Republic, John Judis called it a "disappointing muddle" that "got no style points," while John McWhorter, moonlighting from his Language Log day job, called the speech "worthy of marble" and pointed in particular to Black English influences on Obama's cadences, though he didn't develop the point in detail. And Stanley Fish pronounced the speech a paradigm of paratactic prose, which in its nature "lends itself to leisurely and loving study," and having duly allowed himself to "linger over each alliteration [and] parse each emphasis," predicted that it would be studied in a thousand classrooms: "canonization has already arrived."

Those are the criteria people always bring to this sort of address: Was it memorable? Marmorealizable? Did he stick the landing? It's understandable, a way of flattering ourselves that ritual oratory still matters. But I have the feeling Obama and his writers knew better.

Of course it was a very memorable event, on a historic, make that epochal, occasion. And the speech is sure to be memorialized — in fact Penguin Books is already on it.

But if the speech was well turned, it wasn't memorable. What's more, it didn't need to be memorable. It couldn't have been memorable. And my guess is that nobody tried too hard to make it memorable. As I put the point in a "Fresh Air" piece that aired today [full text here ]:

Obama’s speech made all the required moves: it was grave but not doleful; resolute but not belligerent, eloquent but not grandiloquent. Its acknowledgments were eclectic: Biblical allusions, a nod to Tom Paine, a shout-out to Jerome Kern.

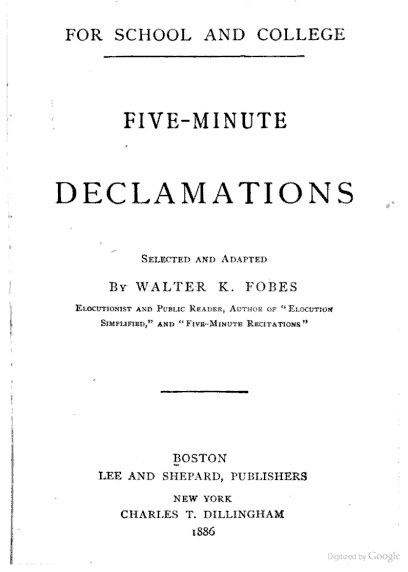

But it wasn’t especially memorable. If we still lived in an age when people compiled collections of great speeches for pupils to memorize and declaim on national holidays, the editor would more likely go with the moving speech that Obama made in Grant Park on the night of the election.

But that isn't necessarily a weakness of the speech.

Ceremonial speechmaking is an unnatural, anachronistic exercise, and I’m not sure whether anybody will ever again give an address as memorable as Kennedy’s in 1961 or Roosevelt’s in 1933 — or that it's a good idea to try.

When you reread Roosevelt and Kennedy’s speeches you realize how rhetorically distant their age was. Take the famous sentence from Kennedy’s inaugural that begins: “Now the trumpet summons us again—not as a call to bear arms, though arms we need; not as a call to battle, though embattled we are, but a call to bear the burden of a long twilight struggle, year in and year out…”

It’s still a stirring line, but you can’t imagine any recent president trying to get away with it. Kennedy was the last president who could comfortably dip into the rich stew of classical figures of speech. “Not as a call to battle, though embattled we are” — that would be both chiasmus and polyptoton. Rhetoricians have been botanizing this stuff for millennia, and by now there's no way to put two words together that doesn't have a Greek label, kept alive by a thin line of English department pedants. There are 67 people in America who live for this stuff.

The medieval scholars called those figures of speech the rhetorical colors, from a Latin term for ornament. They flourished over the centuries when the proper role of literature and oration was the decorous ornamentation of thought, and when politicians and poets drew from the same rhetorical well.

You can still turn up moves like those if you rummage around in T. S. Eliot or Wallace Stevens, but rhetorical ornament is alien to the spirit of modern literature. It still survives in some religious traditions; those flourishes come naturally to a Jesse Jackson or Joseph Lowery, though they sound a bit more forced coming from the energetically affable Rick Warren. But for the most part, the figures are reserved nowadays for advertising slogans, bumper stickers, and the titles of country songs — they’re the linguistic equivalent of stunt riding.

Take the figure in Kennedy’s "ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country” and "we must never negotiate out of fear, but we must never fear to negotiate." The classical rhetoricians called it antimetabole, though modern speechwriters prefer to refer to it as the reversible raincoat. Politicians are still irresistibly drawn to it. Bill Clinton had his "People are more impressed by the power of our example than the example of our power." John McCain had "We were elected to change Washington, and we let Washington change us." And Hillary Clinton went with "The true test is not the speeches a president delivers, it's whether the president delivers on the speeches” (an example not just of antimetabole but of antanaclasis, where the same word is used twice in different senses).

The figure has its roots in Shakespeare and Milton. It's in Blake’s "Never seek to tell your love/Love that told can never be” and Kipling’s "What should they know of England who only England know?" Frederick Douglas used it when he said “You have seen how a man was made a slave; you shall see how a slave was made a man."…

But to modern listeners, the pattern is more likely to bring to mind the syntactic two-step of slogans like "When guns are outlawed only outlaws will have guns" and "I am stuck on Band-Aid, and Band-Aid's stuck on me.” Or in its pure classical form:"Starkist doesn't want tuna with good taste, Starkist wants tuna that tastes good." It’s as catchy as ever, but it can’t be the vessel for a deep idea anymore.

Of course Obama’s speech was dotted with some of the other turns and figures that ceremonial addresses require. "A nation cannot prosper long when it favors only the prosperous” — that was polyptoton, where a word is used in two different ways, as in FDR’s “nothing to fear but fear itself.” It’s a tidy aphothegm; you had the sense somebody fought hard to keep it in there. And there was a soupçon of catachresis in "the bitter swill of civil war and segregation," in a passage that Obama read with rising intonations that I heard as an evocation of the language of Martin Luther King. But Obama didn’t do a lot of rhetorical overreaching — he did just what he needed to do to nail the event. No, it wasn’t a speech for the ages. But I found it reassuring that he kept his coat on right side out.

As I was preparing to tape this piece on Wednesday, when everybody had moved on to the Guantanamo closing and the Clinton and Geithner hearings, a friend said to me, "Was there ever an inaugural address that became old news so quickly?" I don't know. But paratactic or no, nobody seemed to have much interest in lingering over it by then — Obama least of all.

jock burnsnight said,

January 24, 2009 @ 5:06 am

In the best Sam Cooke tradition I don't know much about history, but wasn't the Gettysburg Address similarly disdained for its lack of floridity and anything memorable? Only slowly did it resonate in the American consciousness. A few of Obama's lines are doing that already. Maybe his Chicago speech was better overall but his allusive, discursive style is both effective and impressive — and we'll hearing a lot more of this inaugural speech in the future.

Crito said,

January 24, 2009 @ 8:27 am

Very interesting, GN, thank you.

But can you really declaim a speech (or collection thereof)? 'Declaim' is usually intransitive, and when transitive I think its object is an intentional object; a content. You can declaim your views, or your cause, but not (I think) your speech.

Geoff Nunberg said: Hmm… it wouldn't be the first time I got one of these wrong. But no, the OED gives cites for the transitive use of the verb from the 16th century onwards, including Scott's "He then declaimed the following passage rather with too much than too little emphasis" and Stevenson's "In declaiming a so-called iambic verse, it may so happen that we never utter one iambic foot." And a Google Book search on "declaim * speech" turns up 600 hits, virtually all of them transitive: the first is Dickens's "Kindly declaim Othello's speech." I wouldn't be at all surprised, though, if it turned out that people talk about declaiming things less often than they used to, and like a lot of other things, subcategorizations tend to wither with desuetude.

Dan T. said,

January 24, 2009 @ 8:58 am

Carly Simon had the lyric "So my mind is on my man, got my man on my mind", but here despite the reversal the two phrases actually mean the same thing.

Kennedy's inaugural speech was actually in 1961, not 1963; however, his famous "Ich bin ein Berliner" speech was in '63.

Geoff Nunberg said: Oh boy. How many ways are there to say "Duh"?

Mark F. said,

January 24, 2009 @ 9:24 am

I think the speech to hold this one up against is his speech from the 2004 Democratic convention, and my take is that it doesn't quite meet that standard. In the long term, the measure will be whether there is a quote from the speech that everyone remembers, and right now I'm not seeing what that would be. The "fear/negotiate" line is pretty good, but all most people remember from Kennedy's address was the "Ask not" line. The only words I know from Roosevelt's first inaugural was the "nothing to fear" line.

mgh said,

January 24, 2009 @ 9:43 am

The sustained antimetaboclasiptotons come across, for me, as a rhetorical parlor trick that brings to mind the doubletalk of the superhero "The Sphinx" from the movie "Mystery Men":

and, my favorite:

These devices are better used like exclamation marks than like commas. When such elevated rhetoric is sutained throughout a speech, as in the inauguration, it begins to sound — to me — more like parody than prosody.

For example, I was thrown by a metaphorical series Obama opened with, referring to inaugurals given in "rising tides" and the "still waters of peace" as well as among "gathering clouds". I see they're all weather, but I was mentally aboard the ship of state, peering at the sea, when suddenly he began talking about the sky. I think its placement right at the opening had as much to do with my reaction as the slightly-mixed nature of the metaphor itself.

Mark F. said,

January 24, 2009 @ 9:50 am

Something was bothering me about what Geoff was saying, and I just figured it out.

I don't think that's so. It could have been made memorable, it could even still turn out to be memorable, and it would be a good thing for him if it were. Even with the decline of the place of oratory in our culture, this was a speech people wanted to hear; and if people remember it, and repeat (parts of) it, they will be helping Obama make his case for the things he wants to do. And I think people do remember his 2004 speech, just to prove that it can still be done.

Geoff Nunberg said: Well, as I said it's almost certain to be memorialized, and given the significance of the occasion maybe should be, but I don't know that that will necessarily entail that it was memorable ("Worthy of remembrance or note," as the OED defines it). I don't mean to suggest that a speech can't be memorable for us, only that the rhetorical devices required of ritual oratory (like the inaugural, but not, say, like the 2004 keynote or the Grant Park speech) impede remembrance-worthiness these days. So the question for Language Hat (following post) is whether anyone could utter a remembrance-worthy antimetabole or polyptoton in one of these things anymore. My guess is no — it would be hokey in virtue of its form. Noting to do with left-right.

language hat said,

January 24, 2009 @ 10:26 am

I agree with Mark F.: it goes way too far to say "It couldn't have been memorable." If "nobody tried too hard to make it memorable," that was choice, not necessity. While I take the point that the times call for action, not mere oratory, that doesn't mean oratory is useless, let alone offensive or unthinkable. Great speeches help drill ideas into people's consciousnesses; I happen to think "ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country” is a pernicious idea, but it was far more effective for being so memorably expressed. And (if you will forgive me a momentary lapse into the political discussion I normally deplore on language blogs) the insistence on not being too memorable or eloquent seems to me of a piece with the refusal to be "too progressive," the insistence on watering down the impulses that made so many people so excited about him in the (surely vain) hope of warming the hearts of conservatives so that they will go along with his vision. The man should have the courage of his rhetoric and his ideas.

Fritinancy said,

January 24, 2009 @ 12:08 pm

Thank you for "marmorealizable," an apt, elegant, and memorable coinage.

nichim said,

January 24, 2009 @ 12:44 pm

Thanks for the interesting discussion, here and elsewhere. Since Obama has such a reputation as an orator, and his inauguration was so historic, the expectations for this speech were astronomical. I think the non-compliance of this speech with the expectations can be seen as a counter-measure to what I've heard referred to as the "collective deification" of our new president: now that we've elected Obama, he's going to make everything better by saying magic words. The theme of the speech seemed to be that we have a hard row to hoe and we all have to bend over and get to it, presidents and citizens alike. Before he was president, Obama was criticized for being "only" an orator. Now that he has the power to act, perhaps he's trying to put the oratory in the back seat so that he can let his actions (and those of the citizenry) speak louder than words.

The other Mark P said,

January 24, 2009 @ 4:25 pm

Great speeches help drill ideas into people's consciousnesses

You know, I can't recite a single line from any speech for any of my country's political leaders. They don't put any full speeches on TV or quote them extensively in the papers here.

I can think of a few quotes from non-US leaders, but not since WWII.

On radio or in print, it is the words that matter. On TV it isn't. It's the manner of their delivery.

I'm with Geoff — the day of great speechifying is past. Odd that the US, which brought us the sound-bite should appear to be a laggard in this.

dr pepper said,

January 24, 2009 @ 4:29 pm

Personally, i think the tagline of the inaugural is not something that Obama said, it's what one of the commenters said that was reported on one of those overly chatty news shows: "Mr. President, how can i help?".

language hat said,

January 24, 2009 @ 5:58 pm

the day of great speechifying is past

2004 was so long ago…

jah said,

January 24, 2009 @ 6:33 pm

A shout-out to Jerome Kern? Surely that should be a shout-out to Dorothy Fields.

You're quite right, as I mentioned in an earlier post — or rather it's a shout-out to both of them (when you say "La donna è mobile," after all, you're alluding to Verdi and not just to Francesco Maria Piave). And in a perfect world, Fields's name would be as easy to drop into an NPR piece unexplained as Kern's would.

Rick Robinson said,

January 24, 2009 @ 7:54 pm

For a short speech, appropriate to a 'high' and formal occasion, the inaugural had a lot of policy meat to it, so it may end up being more memorable in retrospect than at first blush.

If I were asked out of the blue whether I remembered any lines I would probably say no. But when I sat down the next day to write a piece for an online journal, language from the speech bubbled to the top of my mind – and I ended up deleting my initial effort and writing about a line in the speech. (Shameless pimping: http://www.europeancourier.org/160.htm)

Tadeusz said,

January 25, 2009 @ 5:26 am

Re "declaim". Aren't you two gentlemen arguing about two different senses (uses) of the word?, one, to recite (transitive), the other, to protest against (intransitive)?

No, Crito is right about there being an intranstive use to mean "To speak aloud with studied rhetorical force and expression,' as the OED defines it, though there is also a use to mean "inveigh." Google Books turns up, e.g., "it is usual for masters to make their boys declaim on both sides of the argument" (William Dwight Whitney), "By 1562, boys in the highest form declaim on play days before large audiences," "He accustomed himself to declaim alone, with his mouth almost full of pebbles," and so on.

Mabon said,

January 25, 2009 @ 12:42 pm

I concur with Nichim, who wisely has Obama putting the emphasis on the doing, rather than the saying. I thought Obama's speech was appropriate to the occasion given the considerations mentioned by Nichim and others; it was not dazzling, nor should it have been.

On another note, I thoroughly enjoyed the benediction given by Rev. Lowery. His oratory started off slowly, almost falteringly, and gained strength and momentum as he steered toward its conclusion. For me, it was the most memorable speech of the day.

Sili said,

January 25, 2009 @ 3:11 pm

Well, the people I hang out with are already cheering the acknowledgement of "nonbelievers" and the promise to "restore Science to its rightful place".

And elsewhere I've seen great joy at the "we reject as false the choice between our safety and our ideals" being accompanied with a closeup of Bush in the transmission.

Whether I'll remember any of this in a month, though …

Kimberly Belcher said,

January 26, 2009 @ 12:29 pm

I wonder if Obama's speech(es) are just being remembered differently?

There are already, no doubt, several hundred of these remix-tributes on youtube. I don't find that one particularly compelling, but that's not the point — if any one of those reaches the power and popularity (perhaps even the power or the popularity) of will.i.am's "Yes We Can," Obama's inaugural address will indeed be remembered.

Of course, that speech was, I think, more rhetorically effective, but the historic moment of the inaugural, as many commenters have observed, motivate its being made memorable in this way. In fact, it's even hard for me to judge how much I remember the rhetorical effectiveness of the "Yes We Can" speech through the lens of such tributes.

Killer said,

January 28, 2009 @ 5:36 pm

Geoff wrote: "I am stuck on Band-Aid, and Band-Aid's stuck on me.”

Should be " 'cause," not "and" … but also, to me it always sounded like:

"I am stuck on Band-Aid, 'cause Band-Aid stuck on me"

— i.e., past tense, making the point that it has remained sticking to me over time. The lyrics are all about how well they stay on, even if used on a flexible joint, underwater, etc.

I would interpret "Band-Aid's stuck on me" as present tense ("Band-Aid is stuck on me"). It could also be perfect tense ("Band-Aid has stuck on me"), which might make the most sense, given that the kids are wearing them in the commercial as well as describing having put them through the paces.

But for 30+ years I'd swear I've been hearing " 'cause Band-Aid stuck on me."

(After awhile they amended it to "I am stuck on Band-Aid brand," by the way — at first in only the first line, but more recently in the ensuing ones, too.)

Famously, Barry Manilow wrote the song; I don't know whether he wrote the lyrics or only the music.