Empirical Foundations of Linguistics

« previous post | next post »

I gave a talk a few weeks ago at the Laboratoire de Phonétique et Phonologie in Paris, founded in 1897 by L'abbé P.-J. Rousselot. Antonia Colazo-Simon took this picture of l'abbé and me:

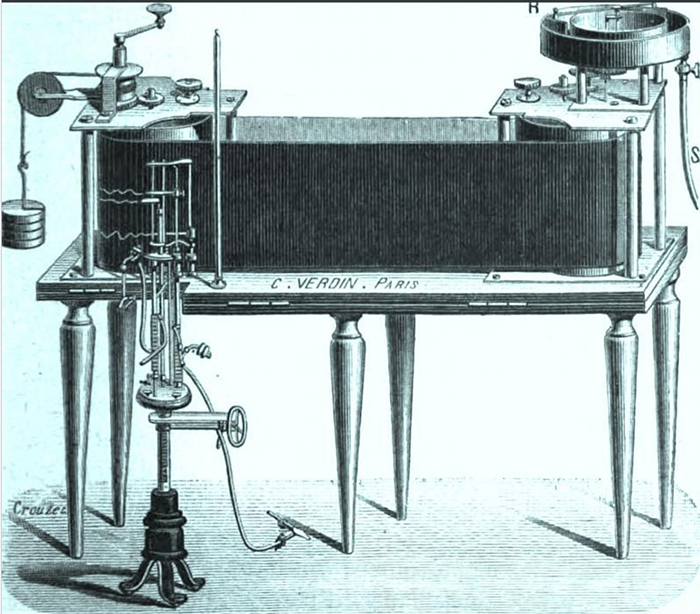

The picture below, from the cover of the first volume of L'abbé Rousselot's Principes de phonétique expérimentale (1897), shows the elegant mechanical complexities that used to be the basis of phonetic measurements:

Using an a device of this type, Rousselot was the first scientist to note the lengthening of phrase-final syllables.

The current occupant of L'abbé Rousselot's chair is Jacqueline Vaissière. She is also the director of the newly-formed Projet EFL, which joins the LPP with 13 other Paris-area UMRs ("unité mixte de recherche" = "mixed research unit") in a Laboratoire d'excellence. EFL is an English acronym — "Empirical Foundations of Linguistics" — for an organization whose full name in French is Fondements empiriques de la linguistique : données, méthodes, modèles ("Empirical foundations of linguistics: data, methods, models").

This is one of the 100 "Laboratoires d'excellence" ("labex") recently established by the French government. The fact that at least some of these have official English-language names may surprise you. Even more interesting is the fact that the applications for these 10-year grants, submitted last year, were encouraged or perhaps even required to be in English. This is apparently part of the French government's effort to increase the international visibility of French science.

EFL's proposal included this summary of planned research activities:

Planned research activities are organized in seven collaborative strands corresponding to areas where the partnering research teams have already got successful results. The five vertical strands each take on a new challenge, on:

(1) Phonetic and phonological complexity;

(2) Experimental grammar in a cross-linguistic perspective;

(3) Typology and dynamics of linguistic systems;

(4) Language representation and processing from a lifespan perspective

(5) Computational semantic analysis.

The two transversal strands (Language resources; Experimental methods) allow for the

sharing of resources (lexica, corpora, databases), existing methods and platforms. They will foster scientific breakthroughs and innovation through the development of new resources and platforms and corresponding methods and best practice. These transversal strands will play a crucial role for the project as a whole.

[It will no doubt occur to some of you that the English-language acronym "EFL" is already in common use for "English as a Foreign Language". This is not unknown to Jacqueline and others in Paris, though I'm not sure what it means for future modes of reference to the new organization, which is barely getting started. During my visit, I mostly heard it referred to as "le labex".]

Dan T. said,

July 26, 2011 @ 11:11 am

Why is a French group using an English initialism, when English-speaking groups feel compelled to use bizarre letter-orderings like IOL for International Linguistics Olympiad in order to avoid offending the snooty French?

Coby Lubliner said,

July 26, 2011 @ 12:59 pm

How about FIFA (Fédération Internationale de Football Association), which is usually misrendered in English as "Federation of International Football Associations"? (Its actual name in English is International Federation of Association Football.) Similarly for UEFA.

Barbara Partee said,

July 26, 2011 @ 1:01 pm

@Dan T — There are 4 presuppositions in your question that I heartily disagree with. Why does a chauvinistic and parochial English speaker feel compelled to describe majority word orders as bizarre and gratuitously offend our open-minded English-speaking readers and our non-snooty non-English-speakers? (Hmm, how many presuppositions I got in depends on how many of my modifiers you take as non-restrictive, I guess.)

Chris Waigl said,

July 26, 2011 @ 1:46 pm

I've come to the point that I'd appreciate a Like button on blog comments (Oh, no!) for Barbara Partee's comment. (As an aside, another initialism that's not quite right for either English or French – a nice idea to share the not-quite-rightness – is "UTC".)

Thanks, Mark, for the dispatch from France. Also, if "EFL" may feel slightly tortured, "labex" on the other hand is such a typical French way of clipping an overlong institutional name.

Ran Ari-Gur said,

July 26, 2011 @ 1:46 pm

@Dan T.: Even if we accept your position that the reason for these letter orders is to avoid offense — the rest of your comment makes no sense. You seem to assume that offense avoidance should be unidirectional: "If English-speakers seek to avoid offending the French, then why should the French seek to avoid offending English-speakers?" I guess I should therefore do my best to offend you, so as to prevent your offending me; so whereas my first instinct was to point that your assumption is far out of line with normal social interaction, I will instead just say that you must be a sociopath or an idiot.

JFM said,

July 26, 2011 @ 1:52 pm

They could have gone with EFoL.

J. W. Brewer said,

July 26, 2011 @ 2:11 pm

I couldn't come up with a good quick and dirty way to see if the French initialism FEL means something to Francophones as prominent as EFL might mean for Anglophones. But there's an interesting related question here raised by myl's note about the EFL people seeking grant proposals written in English. Different academic disciplines vary in terms of how English-focused they have become worldwide. My impression is that in some parts of the humanities (e.g. classics and philosophy; also theology and biblical scholarship) lots of scholarly articles and monographs are still being cranked out in French and German, with scholars at home in those languages not feeling obligated to publish in English if they want to have any impact outside their home countries. In physics and other hard sciences, by contrast, my impression is that these days French- and German- speaking researchers are more likely to feel the need to publish in English for maximum impact. So where is linguistics on that continuum? Has it reached the point where if you want a critical mass of other scholars to care about the really cool data you've discovered doing years of fieldwork on a language with only 300 speakers somewhere in the Amazon, you'd better publish your results in English?

Mark Liberman said,

July 26, 2011 @ 2:30 pm

@J.W. Brewer: "… myl's note about the EFL people seeking grant proposals written in English."

Actually, as I understand things, it was the MInistère de l’Enseignement supérieur et de la Recherche ("Ministry of Higher Education and Research") who encouraged the use of English in the proposals for this large nation-wide program. English-language proposals may have been preferred because of the need to recruit experts from other countries to judge the submissions.

John Roth said,

July 26, 2011 @ 6:21 pm

I've always heard it as ESL – English as a second language. EFL is a new acronym for me. A quick Google shows approximately 93 million hits on ESL; only one of the first page hits is not for English as a second language (it's the Eighth Street Lounge.) It shows approximately 18 million hits for EFL, split 4 for English as a Foreign Language and 5 for several others. So for a first approximation ESL is about ten times as frequent as EFL. I wouldn't think there would be all that much confusion.

J Lee said,

July 27, 2011 @ 12:13 am

@ John Roth

i believe EFL refers more specifically to the teaching of English as a second language while physically in non-English-speaking countries.

[(myl) Unfortunately, the proposal to call the pseudo-language of bilingual phrase books "effle" has never caught on.]

Ben Hemmens said,

July 27, 2011 @ 2:31 am

My posting finger was twitching when I saw Dan's post, but sometimes it pays just to wait ;-)

Yes, grant proposals are routinely prepared in English all across Europe because they are sent to international referees.

[(myl) But France is really not "all across Europe" in this respect, as in several others. For example, the Ministère de l'Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche doesn't (as far as I can tell) have an English-language version of its main web page, though the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung does.]

I tend to just say ELT.

Ben Hemmens said,

July 28, 2011 @ 4:43 am

I wouldn't venture an all-across-Europe generalization about the prevalence of decent English versions of ministerial websites, except to guess that it's patchy and may vary a lot even from ministry to ministry in a country.

But for grant proposals, I'm pretty sure that across a wide spectrum of academic disciplines they are usually written in English from beginning, not translated. The switch has happened in Austria within the last 15 years, and on the introduction of international peer review for all academic grants, it became a requirement.

Slowest on the uptake of things like this are regularly not the French, but the Italians and especially the Spanish.

Damien Hall said,

July 28, 2011 @ 10:08 am

@John Roth: In the UK, EFL is a more usual abbreviation than ESL for something that means 'English for non-native speakers', I think. It was certainly the first acronym I (a Brit) knew for that. On a very quick-and-dirty Google (the two acronyms in sites with the .uk country-code), in the UK EFL seems to mean 'English as a Foreign Language' much more often than ESL means 'English as a Second Language'. There are 766,000 results for EFL and, on the first page, only one is not 'English as a Foreign Language'; while there are 1,710,000 results for ESL, on the first page six of the ten mean something other than 'English as a Second Language'.

As to where linguistics stands with regard to publishing in English if you want international impact: as far as the French are concerned, I think the subject is quite far towards the 'publish in English' end. The vast majority of modern publishing by French people on phonetics is done in English, and other sub-disciplines are similar. That said, in some sub-disciplines there is a 'French sub-culture', if I can call it that; a distinctive French way of doing things which the French themselves might call franco-français, and which means that in those sub-disciplines more publication happens in French, as more of the people who will be interested in reading things done in that approach are themselves French. An example is sociolinguistics: what the French call (unadorned) sociolinguistique is often what Anglophones might these days call 'interactional sociolinguistics' or 'sociology of language', and so a 'sociolinguistic study' of a given area may mean something quite different to a French person than it would to someone trained in the Anglophone world. Thus(?), there is more publication in French about the sociolinguistics of France than there is in some other fields, because many people interested in reading work done in the French approach (though not all) will themselves be French. There is, of course, also some publication in English about the sociolinguistics of France, but what the two sets of authors mean by 'sociolinguistics' may or (more probably) may not be the same.