Absolute pitch: race, language, and culture

« previous post | next post »

A couple of days ago, Geoff Pullum illustrated "The science news cycle" by citing an article that told us "You can develop musical skill comparable to Hendrix and Sinatra — if you learn an East Asian language." Geoff might have cited some other articles exhibiting a depressingly wide range of other misunderstandings of the same research, like "Find Out If You're Tone Deaf; Plus, Are Asians Naturally Better Musicians"; "The key to perfect pitch lies in tonal languages"; "Chinese languages make you more musical: Study"; etc.

The basis of the news reports was a paper presented at the Acoustical Society of America's 157th Meeting: Diana Deutsch, Kevin Dooley, Trevor Henthorn, and Brian Head, "Absolute pitch among students in an American music conservatory: Association with tone language fluency", Paper 4aMU1, presented on Thursday Morning, May 21, 2009.

The link just presented was to the 200-word abstract in the (now online) conference handbook. The source of the media connection was probably the "lay language version" also offered on the conference web site: "Perfect Pitch: Language Wins Out Over Genetics". The route of the media connection was (I believe) via a story by Hazel Muir in the New Scientist, "Tonal languages are the key to perfect pitch", April 6, 2009, along with a press release by Inga Kiderra in the UCSD publication relations office ("Tone language is key to perfect pitch, 5/19/2009).

The provisioning of "Lay Language Papers" is part of the Acoustical Society of America's effort to reach out to the media (the online "press room" is here). I'm a member of the ASA, and I applaud this effort. One obvious benefit is that the "lay language papers" are written by the researchers themselves, not by PR people. More scientific societies should do this kind of thing.

But I'd like to draw your attention to a couple of points that were left out of yesterday's discussion.

First, we have a somewhat-controlled experiment in media uptake here — there are 37 Lay Language Papers available from the 157th ASA Meeting (out of hundreds of presentations at the meeting), and it's predictable that Geoff didn't see a story on "Prediction of Noise from the Portland International Raceway", or "Singers' preferences for acoustical characteristics of performing spaces", or "Passive Acoustic Detection of Herring Size". (Though I must note for the record that analysis of herring sounds has previously been covered in Language Log, following the lead of that great popularizer of linguistic research, Dave Barry.)

On the other hand, I'm surprised not to see more uptake (so far) of Suzanne Boyce et al., "Women get more nasal when they're sleepy", or Benjamin Munson et al., "What Makes a Vowel Sound Gay?", or David Baslau, "Can Noise from Race Cars Break Glass?", or Lawrence D. Rosenblum, "Are Hybrid Cars Too Quiet?".

Perhaps the race-language-music connection trumps women who want to go to bed, fast cars, and possibly-unsafe green alternative vehicles? I doubt it. There's no doubt a random factor involved here, but also, many researchers have their own media connections, and Prof. Deutsch is known to be especially well plugged in. (The skills of the UCSD publication relations people, and Prof. Deutsch's good relations with them, probably also played a role.)

I need to warn you that my second point is neither a joke nor a criticism of the media, but a discussion of the the scientific questions raised by Prof. Deutsch's research.

OK, for those of you who are still here: Leaving aside entirely the question of whether absolute pitch will make you a better musician or not, it's well established that absolute pitch is more common among Chinese music students than among American music students. One source of evidence is an earlier study by Prof. Deutsch and colleagues, whose lay-language version is "Perfect Pitch in Tone Language Speakers Carries Over to Music: Potential for Acquiring the Coveted Musical Ability May be Universal at Birth", 148th ASA Meeting, 2004.

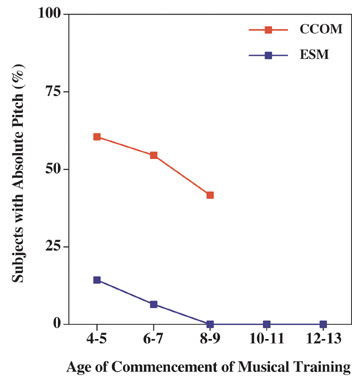

This earlier study found a much higher rate of absolute pitch ability among students at the Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing, compared to students at the Eastman School of Music in Rochester:

That 2004 paper argues that the striking difference between Chinese and American music students is due to the effects of early experience with a tone language, but grants that

It may alternatively be hypothesized that the differences between the two groups found here are due to dissimilarities in brain structure which might be genetically determined. Indeed, both critical period and genetic factors might be involved.

The 2009 Deutsch et al. paper, so egregiously misreported in the article that Geoff cited, is an attempt to tease apart these hypotheses, by looking at the prevalence of absolute pitch in students of Chinese ancestry with varying degrees of tone-language fluency. And it certainly accomplishes one of its goals, which is to undermine the view that the effect is largely or entirely due to genetic effects.

However, it seems to me to be less convincing in making the argument that experience with a tone language is the critical factor, since an alternative explanation in terms of the process of selecting and training music students in China remains viable.

Because the admirable ASA "lay language versions" are not (necessarily) more popular presentations of more substantial scientific papers — rather, they're popular presentation of research whose only other version may be the 200-word abstract in the meeting handbook — there are lots of things about the 2009 research that we don't know. And if I play the advocatus diaboli role traditionally assigned to the reviewers of scientific papers, it's easy to think of alternative explanations for the data that Prof. Deutsch presents.

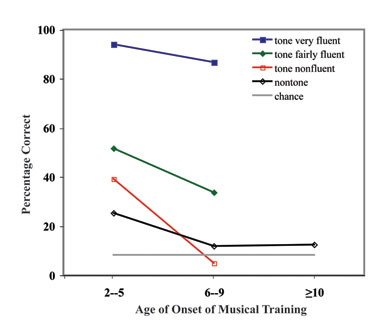

She and her colleagues tested 203 students at the USC Thornton School of Music. These were divided into four groups:

- nontone (Caucasian, speaking only "a nontone language such as English");

- tone very fluent (both parents primarily speaking an East Asian tone language)

- tone fairly fluent (both parents primarily speaking an East Asian tone language)

- tone nonfluent (both parents primarily speaking an East Asian tone language, but "I can understand the language but don't speak it fluently")

The basic finding was that those in the tone very fluent group were much better at identifying and naming musical pitches than the others, with the tone fairly fluent group somewhat better than the rest:

But there's another factor that must be highly correlated with the categorization of music students by tone-language fluency, namely the country where the students were raised and initially educated. Presumably most of the tone very fluent students were raised and initially educated in China; none of the nontone students were; the tone nonfluent students almost certainly weren't; and the tone fairly fluent students probably were mixed in this respect.

And perhaps there's something about early musical training in China that selects students with absolute pitch, and/or develops this ability in students who have the potential to do so. This might be a set of testing procedures for identifying musical talent in young children, which explicitly or implicitly tests the ability to recognize pitch classes; it might be a way of teaching music that favors or rewards the ability to recognize pitch-classes as well as intervals; it might simply be a wide-spread belief that the ability to identify pitches is an important aspect of musical talent.

Such cultural and educational structures might encourage the development of skill in identifying pitches (which is certainly trainable to a degree), or they might simply select and promote kids who natively possess this skill to a greater extent.

Other factors, such as the type of instrument taught at a young age to the Chinese students who wind up at USC, might also play a role; the point is that it's potentially misleading to identify fluency in Chinese as the key factor in a situation where it's almost perfectly correlated with other perhaps-relevant factors, specifically the extraordinary winnowing process that leads a microscopic proportion of Chinese native speakers to end up in music school in California.

(Note, by the way, that the performance of the tone very fluent group from USC seems to be quite a bit higher than that of the CCOM students cited earlier; this is consistent with the hypothesis that absolute pitch confers an advantage on Chinese music students even at the level of selection for study abroad.)

In their lay-language paper, Deutsch et al. do attempt to address the question of early selection and training in China:

In a further analysis we divided the ’tone very fluent’ speakers into two groups: those who had been born in the U.S. or arrived in the U.S. before age 9, and those who had arrived in the U.S. after age 9, and we found that the performance of these two groups did not differ significantly.

But as advocatus diaboli, I don't find this very convincing, for two reasons. First, the key selection process might well take place before age 9. And second, especially in a study this small, the phrase "the two groups did not differ significantly" may not be very meaningful.

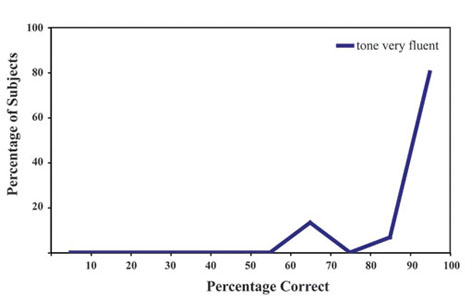

We are not told how many subjects were in each of the four categories — but a graph showing the percentage of subjects across scores for the tone very fluent group, suggest that this subset may have had just 20 subjects in it altogether:

(There are three scores with non-zero numbers of subjects, which appear to correspond to 15% of subjects at 60-70% correct, 5% of subjects at 80-90% correct, and 80% of subjects at 90-100% correct. This would work out if the number of subjects at the three non-zero scores were 3, 1, and 16, respectively, explaining the quantization. Note that the comparable figure for the nontone group is much less coarsely quantized.)

So it might well be that the number of students in the tone very fluent group who "were born in the U.S. or arrived in the U.S. before age 9" might be very small indeed — and lack of a significant difference might therefore not be very meaningful.

Let me be clear that Deutsch's hypothesis that (tone-language experience leads to perfect pitch) remains viable. There's nothing in any of this discussion to suggest that it's wrong — I've only expressed some (standard scientific) skepticism about the argument that it's right. A more convincing argument, it seems to me, would compare groups in which ancestry and linguistic experience were orthogonally varied. And these should not be music students — or rather, the sample should treat musical affinities as irrelevant — so that we can be sure that we're not looking at the effects of variation in the cultural process that selects would-be professional musicians

dr pepper said,

May 23, 2009 @ 10:47 am

Perhaps when foreign researchers arrive, the administrators of the chinese school hide the less talented students. And perhaps they cherry pick the initial data when reporting performance.

[(myl) There's absolutely no reason to accuse the administrators and researchers involved of dishonesty. I considered deleting this comment, since it makes an unpleasant, perhaps defamatory, and (I think) highly implausible suggestion without offering any evidence. There have been enough replications of the basic (and quantitatively very large) result that I think we can eliminate falsification of data as an explanation. (See e.g. Gregersen, P. K., Kowalksy, E., Kohn, N. & Marvin, E.W. "Absolute pitch: prevalence, ethnic variation, and estimation of the genetic component" American Journal of Human Genetics, 65, 911-913, 1999.)

It's true that I also offer no evidence that Chinese testing and training techniques for musical education might select for absolute pitch in young children. But this is a reasonably plausible hypothesis that doesn't require us to attribute bad faith to anyone, and it's also reasonably easy to control for it, by looking at the prevalence of absolute pitch (or its functional equivalent) among students in other career tracks.

The hypothesis that someone faked the data is always available; but the usual practice, for good reason, is to rely mainly on the process of replication for smoking it out. ]

D.Sky Onosson said,

May 23, 2009 @ 11:02 am

As a professional musician (making my living at it for nearly 20 years), and part-time linguist, I can say that I know very few, if any musicians who have "perfect pitch". The lack of it in no way impedes anyone from developing incredible musical talent.

Robert Cumming said,

May 23, 2009 @ 12:24 pm

Is this a case where what we really need is interdisciplinary research to sort things out, but where single-discipline research is (for the usual reasons) more or less all we've got?

[(myl) I'm sure that more disciplinary perspectives would be helpful, as usual, but there are already a number of different disciplines represented in the literature on this topic. My impression is that the best thing would not so much be more broadly-based research, as just more research, period. ]

Bill Walderman said,

May 23, 2009 @ 12:26 pm

Dr. Deutsch's website also refers to a 1999 study she conducted that tested for absolute pitch in native speakers of Vietnamese as well as Mandarin. (It was the results of the 1999 study that led her to conduct the 2009 study to determine whether absolute pitch in speakers of tone languages was due to genetic or linguistic factors.) Apparently, in the 1999 study, the Vietnamese-speakers had no musical training, so there was no selection for musical abilities, but it turned out that the Vietnamese-speakers produced results similar to those of the Mandarin speakers, i.e., an ability at a rate greater than chance to replicate pitches in speech more or less precisely. Doesn't this support the argument for a linguistic basis for absolute pitch, as opposed to a process of selection for musical ability?

[(myl) That study deals with production, not perception; and speech, not music. I would predict that English speakers, given a task that leads them to use stereotyped intonational patterns in a controlled setting, would also produce results in which the average pitches for the samples of a given word as read on two different days would differ by an average of about 1.5 semitones (which for a typical adult male speaker, reading in a quiet environment, might about 10 Hz.)]

Thomas Westgard said,

May 23, 2009 @ 12:44 pm

I'm a bit weirded out by the automatic defense of the Chinese linguistics studies. Of course people lie to researchers, and of course researchers fudge results. If there's any verifiable fact about conducting linguistics research, there it is. Linguistic studies raise social class issues, and people feel shame and change their behavior. If that isn't expressly taken into account, questioning the results is good science.

Now, on non-scientific standards, it's rude to question people's conclusions, and scientists, being human, routinely drop scientific standards and behave as social animals, defending "character" of the people who conducted studies. And it's fine and good to be a socially-adept person, it's a goal I'm sure we all share.

However, if there was no protection in a scientific study against introduction of bad data, being polite about it isn't going to make the data any more reliable. In fact, insisting that people be polite will distract them from considering whether good scientific standards were followed. If science always had to be polite, there would never be a study of the prostate. There needs to be an acceptance that rudeness sometimes leads to scientific results that are more reliable and therefore more useful.

[(myl) Science is a conversation, and like all conversations, it requires a certain minimal level of trust in the people you're talking with. When someone says "I found X", it's normal to ask "wait a minute, did you control for Y?", or "couldn't your results be due to Z?". But to ask "did you fake your data?" is a completely different sort of interaction.

And unless someone is using data previously gathered and published by someone else for some other purpose, the only real protection against fraud — other than replication — is trust in the researcher's basic honesty. In the case of Diana Deutsch, who has been doing interesting research in the general area of pitch perception for many years, questioning her basic honesty would be like asking your insurance agent, "wait a minute, how do I know that if my house burns down, you won't just hire a hit man to kill me instead of paying off the claim?"

That might be a reasonable question under certain circumstances, but in the middle of a normal conversation about buying insurance, to ask that question, other than as a bad joke, would bring things to a halt in an unexpected and uncomfortable place — among things, because you could hardly expect that your interlocutor would admit to such plans, and so the question is basically just an empty insult. ]

Tom O'Brien said,

May 23, 2009 @ 12:58 pm

A side question is what exactly "perfect pitch" is. Can it mean the same thing in the A=440 era as it did in the A=415 era?

[(myl) You can read Diana Deutsch, "Absolute Pitch, Speech, and Tone Language: Some Experiments and a Proposed Framework", which says that absolute pitch "is generally defined as the ability to name or produce a note of particular pitch in the absence of a reference note". Obviously the names would be different if the pitch reference is different. I once had a (Japanese) colleague with no musical training or interests, who named pitches in terms of frequency in cycles per second, which she had learned by listening to signal generators. Obviously her naming would have been different in English or in Japanese; or in kilocycles per minute; or whatever. But the point would remain that she could identify a pitch on some absolute scale, without having recently heard a reference tone.]

David Eddyshaw said,

May 23, 2009 @ 1:52 pm

The thing that perplexes me about this,is that tone languages *don't* rely on absolute pitch level, but on relative pitch differences.

So there remains the question: Why *should* speaking a tone language mean that you're more likely to possess absolute pitch?

[(myl) Good point. To the extent that the connection makes any sense, it would have to be something like "speaking a tone language makes you pay more attention to pitch, creating memories that somehow allow you to identify frequencies on an absolute scale without a recent reference point."

For an idea of how Deutsch thinks this might come about, see Diana Deutsch and Trevor Henthorn, "Speech Patterns Heard Early in Life Influence Later Perception of the Tritone Paradox", Music Perception 21(3):357-372, 2004. ]

peter said,

May 23, 2009 @ 1:55 pm

Tom O'Brien, your question is a very good one. The answer has to be "No". Since tuning prior to equal temperament was always relative to a specific key (ie, an instrument would need to be re-tuned in order to play in tune a piece written in a very distant key from the prior tuning), then the labels given to specific sounds are context-dependent. A person with absolute pitch could tell that a note he or she heard was the same as a previous one heard, but he/she could not have given that note a name, since its name depends on the tonic key in question. While an absolute pitch-sense is possible, the names of pitches are essentially relative in non-equal temperament systems.

mollymooly said,

May 23, 2009 @ 2:18 pm

FWIW, The Economist did mention Rosenblum's research on "Are Hybrid Cars Too Quiet?" this month.

Electric cars and noise: The sound of silence

Michael Moncur said,

May 23, 2009 @ 5:23 pm

Whenever I hear about perfect pitch studies, I always hope they'll answer my two pet quandries, and they never do:

1. Is there, in fact, a reliable methodology for testing for absolute pitch? The "absence of a reference note" is harder than it sounds:

a) The room would have to be completely silent except for the note. (I have a suspicion that some cases of "absolute pitch" are people who can detect 60Hz hum in speakers and compare pitches to that.)

b) They could only test one note at a time. If they played more than one, the student could just be using relative pitch after their guess at the first note.

c) They would have to wait a while after each note – an hour at the very least. You could test me for "perfect pitch" and I'd pass with flying colors if I was practicing guitar two hours ago, because some of the tunes I was playing are still running through my head. So they would also have to isolate the students in a silent room for at least an hour before testing them.

d) They should be using pure sine waves as the test notes. Otherwise, as some people mentioned in the previous post's comments, students could be detecting the particular tone quality of the instrument at different frequencies.

2. Is there any evidence at all that absolute pitch makes one a better musician?

Considering the many examples of great musicians who didn't have absolute pitch (Hendrix certainly didn't) and the questionable utility of absolute pitch in the days of classical composers, when an A could be a wide variety of different frequencies…

As far as I'm concerned any absolute pitch study has to answer those two questions before I'll give any credence to its conclusions.

Michael Moncur said,

May 23, 2009 @ 5:31 pm

In response to David Eddyshaw's question about tone languages relying on relative pitch – the study says this:

> The study found that Mandarin and Vietnamese speakers displayed a remarkably precise and stable form of absolute pitch in reciting lists of words 1, 2.

In other words, I think they're saying that while understanding a tone language uses relative pitch, habitual speakers develop their own standard (and often absolute) pitches to use while speaking.

[(myl) Deutsch et al. did find that in reading a fixed list of words, one at a time, in an identically controlled environment, Chinese and Vietnamese speakers produced average per-word pitches that generally differed in pairwise comparisons by only 0.5 to 1.5 semitones, even across two successive days. But others who have studied the production of lexical tones in more lifelike (and thus more variable) physical and linguistic contexts (for the same languages) have found a very different sort of result, namely variation that spans every pitch-class in the octave, and indeed may vary across several octaves.

As far as I know, Deutsch et al. make no claim to the contrary.

If they were claiming that "habitual speakers develop their own standard … pitches to use while speaking", and meant by that that a given tone pattern, even on a given word, will generally be produced in the same way across occasions, then their assertion would be trivially falsified by the extensive literature on the phonetics of lexical tone. But I don't think that's what they're saying.

In the 2004 paper cited above ("Absolute Pitch, Speech, and Tone Language: Some Experiments and a Proposed Framework"), they found that English speakers were just about as consistent as Chinese speakers across blocks of trials within a a single day, but varied somewhat more from one day to the next. But the difference was not an enormous one, and it's easy to think of ways to change the experimental design that might result in a different outcome.

(See Bob Ladd's comment below for an argument that speakers of languages like English and Dutch are in fact just as consistent as speakers of tonal languages in their lab-list-reading pitch productions…)

]

Michael Moncur said,

May 23, 2009 @ 5:38 pm

Following up to my already too-long comment about test methodology…

The study used 36 notes played a second or two apart, using a "piano" sound, and I can hear a low 60Hz hum in their example recording. They don't say anything about isolating the students before the test to account for the possibility of pitch memory.

So I question whether they found any examples of people with absolute pitch at all.

They certainly found *some* difference between the two populations, but it could have just as easily been a difference in relative pitch ability or pitch memory.

Mark Liberman said,

May 23, 2009 @ 6:17 pm

Michael Moncur: Whenever I hear about perfect pitch studies, I always hope they'll answer my two pet quandries, and they never do:

1. Is there, in fact, a reliable methodology for testing for absolute pitch?

Perhaps this is less problematic if we don't assume that "absolute pitch" is something that people either have or don't have, but instead conjecture that there are internal pitch references that may be more or less accessible and more or less stable. That actually seems to be Deutsch's theory. So she's happy to rely on pitch-identification methods that yield individual differences in whatever subject populations she's working with, without worrying too much about whether pitch-memory over a period of hours — or 60 Hz hum from an amplifier — might be provided a reference that would be missing if the subjects were tested after sitting in a sound-isolated chamber for a week.

But there do seem to be some people whose responses to musical pitches are just different from those of the rest of us. I once listened to a recording with a friend with perfect pitch, who insisted on turning it off because the recording engineers had apparently sped it up just a bit to make it sound brighter, so that (according to him) it was about a quarter tone sharp. He'd never heard the piece before — the problem was that as far as he was concerned, it was in (say) G half-sharp major, which was Just Wrong.

2. Is there any evidence at all that absolute pitch makes one a better musician?

None that I'm aware of. But there's good evidence that absolute-ish pitch is much commoner among skilled musicians than among members of the species at large. Of course, the arrow of causation might point in several directions here — perhaps A tends to cause B, perhaps B tends to cause A, perhaps some third factor tends to cause both.

To give a somewhat whimsical example, there's good evidence that dementia (due to traumatic brain injury) is much commoner among professional football players than in the general population. This is obviously not evidence that dementia makes you a better football player.

Thomas Westgard said,

May 23, 2009 @ 6:18 pm

But to ask 'did you fake your data?' is a completely different sort of interaction.

If I understand correctly, your point is this: The scientific process is to accept the representation of honesty, pending an attempt to replicate the data if you feel there's a question. Making an unfounded speculation without following up with a new experiment is not a part of the scientific process. When the question has a nonscientific function, it's reasonable to measure it against nonscientific standards, like rudeness.

Yes, that's very clear and good point!

[(myl) Yes, this is exactly right.

Of course, there are obviously cases where, short of failed replication, accusations of fakery would be appropriate. It's sometimes possible to argue on internal groups that data can't be valid as given — two famous examples are Fisher's (perhaps wrong) argument that Gregor Mendel faked his data on plant genetics (on the grounds that the results were too good to be true), and Leon Kamin's argument that Sir Cyril Burt faked some of the data in his twin studies (again because of too-good-to-be-true results).

(I should also hasten to add that most failures to replicate are not because the original experiment was faked, but because of differences in one or more of the innumerable perhaps-relevant but uncontrolled factors that exist in every experiment. ]

Bob Ladd said,

May 23, 2009 @ 6:52 pm

I mentioned the Deutsch et al. 1999 study (cited by several commenters above) in my response to Geoff Pullum's original post the other day. It seems pretty clear that Deutsch et al. over-interpreted their findings in that case, because in my experience speakers of non-tone languages are just as consistent in pitch level as speakers of tone languages. Brief details here.

dr pepper said,

May 23, 2009 @ 7:37 pm

I didn't mean to offend. But we are talking about people working under a repressive regime with an interest in making their country look good.

[(myl) This might make sense if the only evidence came from the one study at CCOM — though even there, it would require collusion by Deutsch's co-author at the Capital Normal University in Beijing, which is a very different matter from some administrators putting their best foot forward. But there are at least two other studies done on music students in American schools, showing a significantly higher rate of absolute pitch among students of Chinese or "Asian" origin. Specifically, Deutsch et al. 2009 looked at USC students — the regime in California can't even persuade its citizens to balance the state budget, and no one at USC has any motivation to make their "tone language fluent" students seem more likely to have absolute pitch than their Caucasian students. ]

Noetica said,

May 23, 2009 @ 8:07 pm

First, with no small measure of trepidation I comment on the reception of Dr Pepper's post, which I note did not "accuse the administrators and researchers involved of dishonesty". Unfortunately it was the first response, and we cannot rule out that this heightened its salience and its vulnerability. Nevertheless, politics and various modes of correctness (or must I say "caution"?) aside, as Thomas Westgard has pointed out: "Of course people lie to researchers, …". Politics not so aside, some who have had a few unmediated glimpses of the Chinese tertiary education system, or who receive candid reports from participants in it, will not be startled by the hypothesis offered. It is to the credit of Language Log that Dr Pepper's post was not censored. But let's not dwell on the topic of censorship.

Second, without having explored all of the many links, I want to submit another hypothesis. As Mark points out in his later post, "there's good evidence that absolute-ish pitch is much commoner among skilled musicians than among members of the species at large." To add anecdotal evidence, the few élite pianists I know all have absolute pitch. I suspect that absolute pitch is present at the highest levels of musical talent even more strongly than we might predict from its presence at middling levels. Next, ask about the concentration of such élite, egregiously talented students at Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing as compared to their concentration at Eastman School of Music in Rochester. To borrow Mark's wording, a "microscopic proportion" of the pool ends up at the Central Conservatory; its students might be concentrated at the very tip of musical talent more than, say, the students at the Eastman school are. Perhaps, indeed, there is no institution in America sufficiently comparable to the Central Conservatory in this respect.

From this conjectured non-linearity we should expect absolute pitch to have higher representation at the Central Conservatory, even without any of the other factors adduced above. But as usual, the true picture may be a mosaic of causes.

Michael Moncur said,

May 23, 2009 @ 9:58 pm

Mark Liberman: Perhaps this is less problematic if we don't assume that "absolute pitch" is something that people either have or don't have, but instead conjecture that there are internal pitch references that may be more or less accessible and more or less stable. That actually seems to be Deutsch's theory.

That's a good point, and it validates my crackpot theory that absolute pitch is really just a combination of relative pitch and a low-grade case of Tinnitus.

I'm definitely in the camp that believes that being an elite musician is likely to cause absolute pitch, rather than the other way around, but to be fair, the "perfect pitch will make you into Sinatra" argument was purely the media's and not the study's.

Bob Ladd said,

May 24, 2009 @ 2:58 am

The literature makes it pretty clear that early and/or intensive musical training contributes to absolute pitch, and undoubtedly there are ways in which "having" absolute pitch is a matter of degree. But it's important not to lose sight of the fact that, whatever it is, some people just have it and most of the rest of us never will. One of my sons, at the age of about 7 or 8 and having had ordinary middle-class non-intensive piano lessons for at most a year or so, inadvertently revealed that he had absolute pitch: we were talking about a choral piece that he had heard for the first and only time the day before, when I sang in an amateur choral performance, and he named some of the notes. He had no idea he was doing anything unusual – he was just trying to identify which part of the melody he was talking about. (I was so astonished I went to check the score to make sure he was right.) Obviously he was growing up in an environment where music was taken seriously and where he had been provided with names for notes at a relatively early age, but that applies to many many people (like myself) who don't have absolute pitch. This is part of why I concur with Mark's skepticism in the main post – I don't believe that simply speaking a tone language can have such a large effect on an individual's ability to name pitches, and I do believe that other factors, not addressed in Deutsch et al.'s paper, are likely to play an important role in explaining their findings.

Jonny Rain said,

May 24, 2009 @ 7:15 am

Absolute pitch *does* run in families, and nations are very big families.

Bill Walderman said,

May 24, 2009 @ 10:35 am

"Is there any evidence at all that absolute pitch makes one a better musician?"

I've heard some musicians with absolute pitch complain that it's as much a nuisance as a blessing. They find it irritating to hear a piece they know well performed at a slightly different reference standard of pitch (e.g., A=something other than 440) than what they're used to.

A personal anecdote (if I can be indulged): though I don't have absolute pitch, I recently heard a "period" recording of a piece I know well and have even played myself–the Bach d minor concerto for two violins–and it drove me crazy. On reflection, I figured out why: it was performed at a substantially lower reference pitch than the A=440 I'm used to (supposedly at a pitch that was prevalent in Bach's day, though I have my doubts).

Bill Walderman said,

May 24, 2009 @ 10:38 am

As usual, my previous comment was anticipated by myl. Consider it validation of his point.

Benjamin Munson said,

May 24, 2009 @ 11:40 am

Apologies for going somewhat off-topic, but since I was cited in Mark's original post I think I have at least temporary license to do so.

One question that I have struggled with in the last month is what effect, if any, these popular-media lay-language versions of work has. Does it benefit us as individuals our field collectively if our work gets wide attention in the popular media, even if it mischaracterizes our findings? When E. Allyn Smith, Kathleen Hall, and I wrote our lay-language version, we were very careful to write it in a way that conveyed that this was a serious scientific investigation and that it was part of a two-pronged program of research (a) examining social meaning in light of recent developments in formal semantics (i.e., Potts's dissertation), and (b) developing deterministic models of sociophonetic variation, with an eye on the implication that these models have to spoken word-recognition and speech-sound acquisition. Surely we would have increased the likelihood of getting cited in the popular media if we had written a frivolous version of our paper and giving a title like "Work those /æ/s, Girl! Sounding Gay through Phonetic Variation" or something similarly undignified. Kathleen, E. Allyn and I really struggled with this because we wanted to balance the desire to make our work known broadly (particularly important for two brilliant young scholars like Assistant Professor Kathleen Hall and ABD Grad Student E. Allyn Smith, but also important for Perpetually-looking-for-large-grants Associate Professor Benjamin Munson) with the desire to preserve the scientific integrity of our work. Would we really be served well by having our work cited in the Sunday Styles section of the Buffalo News? I ask this question to this group very seriously: would we? Or would this run the danger of making our entire profession look frivolous?

If we consider the plusses and minuses to be cited widely in the popular media, maybe it's easier to understand why Diana Deutsch promotes this line of research (which surely is only a small portion of what she researches) in the popular media. Perhaps we can see her bold speculations about her data as just that, plain ol' bold speculation (which we all do and which is part of the research process), and not as something sinister. For what it's worth, after the 1999 Columbus ASA when her work was first cited widely, I pictured her as a ruthless ball of credentialist ambitions. I was surprised to finally meet her at this ASA (albeit briefly, when she was lost and looking for a meeting room) and see that she's an academic just like the rest of us–very thoughtful and rather Bohemian. (Indeed, when I looked up and saw her my first thought was of Vicki Fromkin, so much so that I almost expected her to turn to me and say in that familiar New Jersey falsetto the statement I heard so often at UCLA in the early '90s, "Ben, would you go upstairs and get my mail for me?")

D.Sky Onosson said,

May 24, 2009 @ 12:28 pm

If some people who have perfect pitch become annoyed or irritated at hearing atypical pitches, I wonder how they react to non-Western music that may use a completely different system and/or set of pitch references?

I find it interesting that most of the discussion on "elite musicians" seems to revolve around Western Classical music (with the exception of Jimi Hendrix, I believe). I can see the utility of perfect pitch in that system, but I wonder if anyone has looked at it in the context of Karnatic music, or Inuit throat-singing, or Argentinian tango? – just to name a few wildly divergent forms of music.

Mark Liberman said,

May 24, 2009 @ 1:15 pm

Benjamin Munson: Does it benefit us as individuals [and] our field collectively if our work gets wide attention in the popular media, even if it mischaracterizes our findings?

Yes, in my opinion. We certainly need better popular discourse about science, and about rational investigation in general; but my (perhaps naive) view is that the best way to get more high-quality discussion is to promote more (and wider) discussion, good and bad both. I argued this at somewhat greater length in a post "Raising standards — by lowering them", 3/7/2005.

So if your ASA "lay language paper" were to promote MSM headlines like "Work your a's, girl", that would still be a step on the road to a better future.

Jeffrey Kallberg said,

May 24, 2009 @ 1:34 pm

Bill Walderman wrote "I recently heard a "period" recording of a piece I know well and have even played myself–the Bach d minor concerto for two violins–and it drove me crazy. On reflection, I figured out why: it was performed at a substantially lower reference pitch than the A=440 I'm used to (supposedly at a pitch that was prevalent in Bach's day, though I have my doubts)."

If you have access to Grove Music Online (or to a library with the print-version Revised New Grove), I recommend reading Bruce Haynes's excellent article on "Pitch", which might help assuage your doubts. The fact of lower pitch in Bach's milieu is quite well established.

Bill Walderman said,

May 24, 2009 @ 2:12 pm

"The fact of lower pitch in Bach's milieu is quite well established." Yes, yes, I know. The standards of pitch in Bach's day can be verified from surviving organs, etc. But I wonder whether there wasn't more flexibility for instruments that didn't have fixed tuning and for vocal music, and more regional variation in pitch, than we can measure today.

J. W. Brewer said,

May 24, 2009 @ 9:21 pm

Korean and Japanese are non-tonal, but native speakers thereof (and their less-fluent or non-fluent American descendents at least in the first generation or two) tend to have somewhat more in common culturally and presumably genetically with Chinese-speakers and their descendents than either do with generic white Americans. Why wouldn't comparing the Chinese or Chinese-American students with other, "toneless" East Asian or East-Asian-American students be the more obvious way to test the tonality-does-it hypothesis? I don't know what the ethnic breakdown of the student body at USC's music school as such is, but it can't be that hard to find, e.g., Korean-American kids with some degree of formal Western-classical-music training within a reasonable radius of the USC campus.

Rory said,

May 25, 2009 @ 11:25 am

Mark's original post remarks that:

"However, it seems to me to be less convincing in making the argument that experience with a tone language is the critical factor, since an alternative explanation in terms of the process of selecting and training music students in China remains viable."

Indeed, Gregersen et al (2007, American Journal of Medical Genetics, 143A pp104-5, DOI: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31595) claim that "the development of A[bsolute ]P[itch] is more highly valued as a pedagogical goal in many Asian countries".

Any Asian music teachers here who can corroborate that statement?

Chaon said,

May 27, 2009 @ 3:25 am

Test native speakers of staccato-sounding languages (Wolof?) to see if they have a better sense of rhythm.

Wednesday Round Up #65 « Neuroanthropology said,

May 27, 2009 @ 10:24 am

[…] Liberman, Absolute Pitch: Race, Language, and Culture Absolute pitch in Chinese vs. Americans – is it due to “race”? Some debunking, as well as […]

Geoff Nathan said,

May 29, 2009 @ 3:20 pm

There is a whole alternative view of absolute pitch discussed (and researched) by Daniel Levitin which argues that everybody has 'absolute pitch' if by it we mean 'ability to reproduce some specified pitch from memory'. If, on the other hand, it means 'ability to name some note having heard it' or vice versa, 'ability to sing some specified note having been given the classical label (e.g.'middle C') then that ability seems to be learned. Levitin showed that virtually anybody, asked to sing some song they learned from the radio/CD/mp3 player (e.g. 'Sing the Beatle's Yesterday') normally start singing at almost precisely the pitch on which the original recording was issued. Apparently we all store absolute pitches.

What is specialized is the ability to label those pitches.

There's more, but it certainly sends the discussion in a different direction.

References can be found in Chapter 5 of Levitin, Daniel. 2006. This is your brain on music. New York: Dutton.

Warren D Smith said,

March 27, 2010 @ 11:49 pm

I suspect AP is caused by neural circuitry (banks of oscillators or resonators) not by the ear.

My reasons:

1) Sacks Musicophilia mentions an MS attack shifted somebody's AP high.

2) Claims have been made that drugs can shift your AP (they did not say what drugs, but I assume neuroactive)

3) Never saw a claim getting a cold or ear infection shifts AP. Never saw a claim getting an ear injury shifts AP (maybe abolishes, but not shifts).

4) AP and RP both break down above about 4500 Hz, although people can still tell in that regime which of two pitches is the higher one.

5) People's AP often shifts high with age, supposedly significantly more than a shift toward low.

Re (1), MS attacks myelin, and reduced myelin would slow down your nerve conduction velocity which would cause your AP to shift high, if it is neurons. If it is ear, I don't see why MS should have effect and why it should have uniform effect.

Re (2), be better if we knew what drugs, but I'm unaware of drugs altering your inner ear elasticity.

Re (3), the absence of evidence is sadly not as good as evidence… too bad none of the scientists studying AP ever asked this question (far as I can tell).

Also it would be interesting to test if getting a high fever temporarily shifts your AP due

to the temperature change.

Re (4), the reason for the breakdown is because consonance is recognized by neural circuitry and neurons cannot operate that fast. So beyond 4500 Hz you can still tell "note X is the higher one" via geography on the cochlea, but cannot perceive consonance.

Well, so, this seems to clearly say AP is about neurons not cochlea geography. Therefore commonly advanced theories that your cochlea changes elasticity with age causing AP shift, are bullshit. In fact, if it were neurons such a change would not shift AP.

Re (5) this is compatible with neurons slowing down and/or lengthening as get older.

Neurons are simply better engineering than cochlea because that way your AP is more immune to ear infections, common cold etc. Also it is known special brain region involved in AP and it is known genes have something to do with AP.

Finally, I have taught myself (I am 99.9% sure I do not have AP)

to measure time (20 seconds) purely mentally to about +-1%. I think everybody can do that with a little practice. Therefore we know neurons have the necessary accuracy to accomplish the job.

Suggested simple tests: if D2O not H2O introduced into inner ear, and perhaps if change the atmosphere to make it He-rich or SF6-rich (helium, sulfur hexafluoride) then the speed of sound changes in the air (or water) but frequencies of test tone do not change. If AP does not shift, that proves it is neurons not ear.

Perhaps can do this with animals not humans. (More ethical.)

Some animals supposedly have AP, like birds.