Cattle raid, spray, whatever

« previous post | next post »

In a Yuletide email message, Victor Mair found holiday cheer in the American Heritage Dictionary entry for spree — not so much the definition (just "A carefree, lively outing", "A drinking bout", or "A sudden indulgence in or outburst of an activity"), but in the etymology and "Word History":

[Perhaps alteration of Scots spreath, cattle raid, from Irish and Scottish Gaelic spréidh, spré, cattle, wealth, from Middle Irish preit, preid, booty, ultimately from Latin praeda; see ghend- in Indo-European roots.]

Word History: A spending spree seems a far cry from a cattle raid, yet etymologists have suggested that the word spree comes from the Scots word spreath, "cattle raid." The word spree is first recorded in a poem in Scots dialect in 1804 in the sense of "a lively outing." This sense is closely connected with a sense recorded soon afterward (in 1811), "a drinking bout," while the familiar sense "an overindulgence in an activity," as in a spending spree, is recorded in 1849. Scots and Irish dialects also have a sense "a fight," which may help connect the word and the sense "lively outing" with the Scots word spreath, meaning variously, "booty," "cattle taken as spoils," "a herd of cattle taken in a raid," and "cattle raid." The Scots word comes from Irish and Scottish Gaelic spréidh, "cattle," which in turn ultimately comes from Latin praeda, "booty." This last link reveals both the importance of the Latin language to Gaelic and a connection between cattle and plunder in earlier Irish and Scottish societies.

So, he explained, "when you go out on your Christmas shopping spree this year, you are essentially raiding the stores and bringing home the booty!"

This clearly falls into the "Too Good to Check" category, so as expected, the metaphor is less vivid in Wiktionary's etymology:

1804, from Irish spraoi (“fun, sport”), of North Germanic origin, from Old Norse sprækr, sprakr (“lively, vigorous, sprightly”), from Proto-Germanic *sprakjaz, *sprakją, *spruką (“branch, sprout, splinter”), from Proto-Indo-European *(a)sp(h)arag-, *(a)sprāg- (“sprout”). Cognate with Icelandic sprækr (“sprightly”), Norwegian spræk (“cheerful, lively”), Swedish dialectal sprygg (“active, brisk”). More at spry.

And the OED's etymology (from 1914, it's true) is a total buzz kill:

Etymology: A slang word of obscure origin: compare spray n.4

The OED gives that 1804 citation as

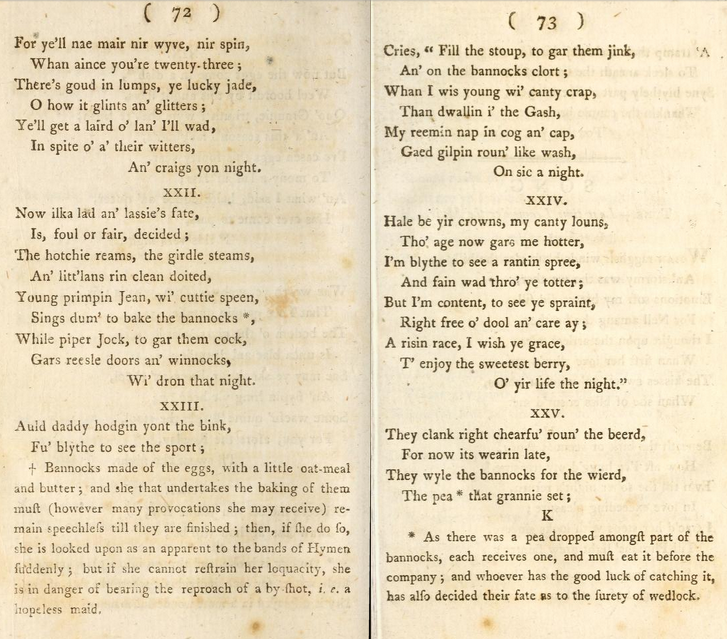

1804 W. Tarras Poems 73 I'm blythe to see a rantin spree.

John Jamieson's Etymological Dictionary of the Scottish Language (Supplement, Vol. 2), 1825, glosses spree as "innocent merriment" and gives a bit more of the poem:

Tho' age now gars me hotter,

I'm blythe to see a rantin spree,

And fain wad thro' ye totter.

According to the Dictionary of the Scots Language, it seems that gar here means "make"; hotter means "shake"; rantin means "boisterous"; and totter is either an adjective meaning "unstable, precarious, unreliable, uncertain", or a verb meaning "to waver, oscillate".

I'm not sure what "thro'" is — maybe what the Dictionary of the Scots Language has under the lemma Throuch, Thruch, Through, meaning "to put into effect", or "to contrive (something's) passage through (a place or process)"; or maybe just the preposition usually spelled "through".

The rest of the poem is here, in William Tarras, Poems, Chiefly in the Scots Dialect, 1804:

John Lawler said,

December 21, 2013 @ 5:27 pm

The entry for the PIE root *ghend- in the 2000 edition of the American Heritage PIE Roots Dictionary.

AntC said,

December 21, 2013 @ 6:04 pm

Idea for a last-minute stocking-filler for LL readers: the dictionary of speculative and mischievous etymology, showing how all words in all languages are derived from (fill in you language of choice).

Yuletide greetings to all!

languagehat said,

December 21, 2013 @ 7:40 pm

The much more recent (than OED) M-W 11th ed. is also a buzzkill: "origin unknown." I dearly love the AHD, but it's willing to get more speculative with its etymologies than I'm sometimes comfortable with (I still remember their suggestion in the 1st ed. that PIE *ekwo- 'horse' might be a prefixed form of the word for 'dog').

Piotr Gąsiorowski said,

December 21, 2013 @ 7:58 pm

Apparently in auld Scotland a cattle raid was regarded as haeing a wee bittie innocent fun.

J.W. Brewer said,

December 21, 2013 @ 8:55 pm

The Táin Bó Cúailnge (often Englished as "The Cattle Raid of Cooley") is about as core a canonical text as there is in the surviving corpus of Old Irish, so, yeah, there's some basis for believing that cattle-rustling was an important form of social/political expression in early Goidelic culture. (The Tain is set in Ulster; the possible impact of the dialect of Ulster Anglophones via Scotch-Irish immigrants on the way cattle rustlers stereotypically talk in mid-20th-century Hollywood westerns can be addressed in another post . . .).

dw said,

December 21, 2013 @ 10:21 pm

The previous poem features the memorable phrase "canty crap". It sounds even better in an imaginary Scottish accent.

djbcjk said,

December 22, 2013 @ 2:16 am

What's the meaning of 'spraint' (two lines down from 'spree' in Tarras' poem? Is it a verb, past tense of some word connected with 'spree'?

maidhc said,

December 22, 2013 @ 2:17 am

May your crowns be healthy, my brisk chaps,

Though age now makes me shake

I'm glad to see a frolicsome spree

And I would like to make my uncertain way through you all

But I'm content to see you leap forward

Ever free of grief and care

It's about traditional festivities on Fastren's E'en, the night before Lent (Shrove Tuesday). Also Fastern's Even, from "fasting". They're making bannocks (recall that this is Pancake Tuesday in England). There are a lot of customs having to do with seeing the future mentioned.

In XXII the piper starts to play, shaking the doors and windows. In XXIII an old fellow sitting on a bench (by the fire, this would be the old kind of fireplace that you could sit in) and hodgin' (trembling) calls out to drink up to make them jink (leap about) as he did in his youth. In XXIV it sounds like they are dancing. The old man would like to totter along with them, but he contents himself with watching.

I find the connection between spraoi and spréidh a bit doubtful because of the different quality of the initial consonants. The Norse connection seems more likely. Gaelic has quite a few words of Norse origin.

I can't find spraoi in the older dictionaries (Dinneen, Dwelly's, MacLennan's and MacBain's), although there is spraidh (the report of a gun) and spréidh (a spark–a different word than the one meaning cattle). Is it used in Scots Gaelic at all? The newest dictionary I have is 1925.

It may have come into Irish from Scots (with the tattie howkers?). The first Scots citation is 1804. If it came from Norse, what happened to it in between?

Quite a mystery.

Victor Mair said,

December 22, 2013 @ 9:04 am

It would be helpful for readers to know a bit more about the "spray n.4" that is referenced in the 1914 OED etymology cited thus:

=====

Etymology: A slang word of obscure origin: compare spray n.4

=====

Presumably it is the same sense of "spray" as that being referenced in the title of the original post, and not what we usually think of when we use the word "spray".

Victor Mair said,

December 22, 2013 @ 9:12 am

Many thanks to John Lawler, Piotr Gąsiorowski, J. W. Brewer, and maidhc for their helpful comments.

This comes from a young Irish-American friend:

=====

Interesting discussion there. The first thing to come to mind when I saw your message last night was the Táin Bó Cúailnge, which J.M. Brewer mentioned in the comments. That epic was translated into English as The Tain by Thomas Kinsella and more recently by Ciaran Carson; a Chinese translation based on Kinsella’s English translation uses the much less cool-sounding 夺牛记 [VHM: Duó niú jì (A Record of Robbing / Capturing / Seizing / Snatching / Reaving / Reiving Cattle)] as a title. In any event, the word for “raid” in that title is Táin.

I’ll run the proposed etymology of ‘spree’ past the Irish-speakers in my household tomorrow. Thomas Kinsella actually used to teach at Temple and lived somewhere in my folks’ neighborhood; not sure whether or not either of these things is still true. The OED is infamous for having “etymology unclear” for words of Irish or Scottish origin, or at any rate that’s the reputation it has.

=====

Victor Mair said,

December 22, 2013 @ 9:15 am

I present this strictly as a source of data:

The Dialect of Cumberland: sproag

d.waugh said,

December 22, 2013 @ 11:34 am

Sorry folks but this is just plain wrong. The word spreidh does not mean a (cattle) raid in any form of Gaelic. I have checked Dinneen, Dwelly and the Dictionary of the Royal Irish Academy – all of them just say cattle or wealth.

Phillip Jennings said,

December 22, 2013 @ 1:41 pm

I dearly wanted to derive 'razz(a)matazz' from the medieval fabric 'rakematiz' (heavy silk with inwoven gold threads), but alas, many centuries intervened.

Victor Mair said,

December 22, 2013 @ 1:58 pm

Nothing to be sorry about, d.waugh.

There's no doubt that spreidh means "cattle" and, by extension, "dowry", etc.

link

link

link

This last citation is particularly interesting for our current inquiry.

The following citation from William Hutchison Murray's Rob Roy MacGregor: His Life and Times is essential for our inquiry, because it directly relates spreidh to cattle raiding. It also provides fascinating information about the causes and mechanisms of cattle raiding. See esp. p. 29, where we find this amazing quotation:

=====

Harsh seasons with heavy loss of stock by starvation hit different districts year by year, and to tide communities over the bad spell, those who suffered most lifted stock from clans with a temporary abundance. The latter would take in turn when their own time of need came. This practice had such real value to clan life that Gaels otherwise law-abiding viewed cattle-raiding not as theft but as a robust form of social welfare, to which everyone contributed. [VHM: emphasis added]

=====

On p. 28, Murray specifically refers to spreidh as "livestock plunder" and discusses it in the context of the great Táin Bó Cúailnge cycle on cattle raiding, which has already been mentioned in the above comments.

Victor Mair said,

December 22, 2013 @ 3:09 pm

From the original post:

=====

According to the Dictionary of the Scots Language, it seems that gar here means "make"; hotter means "shake"; rantin means "boisterous"; and totter is either an adjective meaning "unstable, precarious, unreliable, uncertain", or a verb meaning "to waver, oscillate".

=====

Eric Hamp tells me that the last verbal meaning may be thought of as modified by the adverb "drunkenly".

John Lawler said,

December 22, 2013 @ 4:23 pm

The spr- assonance seems attracted to extrusion, of one kind or another.

maidhc said,

December 22, 2013 @ 4:35 pm

I've always known "totter" as a common English word.

Victor Mair said,

December 22, 2013 @ 6:28 pm

All the entries From 'Foclóir Gaeilge Béarla' under "Spraoi", sent to me as a photograph by Brendan O'Kane, have to do with "sport, fun, merriment, entertainment, spree, and drinking (bout)". Just below, at the bottom of the photo Brendan sent is is an entry on spré1, which is defined as "1. cattle, property…". I'm dying to know what the rest of the entries are for spré.

—————

All right, Brendan just now sent the rest of the spré1 entry to me. It continues with "wealth (in cattle and sheep), dowry". Spré2 is a separate word altogether meaning "spark, ember, small fire".

Eric P Smith said,

December 22, 2013 @ 6:52 pm

Some would go further and remove the word 'otherwise', taking the view that cattle-raiding within Scotland by the needy was fully in accordance with (customary) Scots law.

maidhc said,

December 22, 2013 @ 10:41 pm

In Scots Gaelic spréidh just means cattle. The meaning dowry is only in Irish; it comes from the meaning cattle because in olden times wealth was reckoned in cattle. There's a traditional song "Gan Dhá Phingin Spré" (Without Two Pennies Dowry) that Maighread Ní Dhomhnaill did a very nice recording of, a few years ago. The meaning is that the girl is so desireable that the boy will marry her without a dowry — great praise indeed.

Spré2 is a different word; it even has a different plural form.

d.waugh said,

December 23, 2013 @ 5:19 am

Spreidh just means cattle or property; all this stuff about raiding is beside the point. Etymology is not guesswork. It is possible that the word was borrowed from Gaelic by Scots and underwent a semantic change but there are problems with the form of the word as well – the Scots forms all end in a voiceless fricative but the Gaelic word does not.

Victor Mair said,

December 23, 2013 @ 10:14 am

@d.waugh

Those aren't "problems". Semantic and phonological change are part and parcel of borrowing.

Dan Lufkin said,

December 23, 2013 @ 3:17 pm

Another Norse word in there is gar. Still around in Bokmål as gjøre, Nynorsk as gjere. Not to mention ilka, cuttie, blythe, hale, clank, beerd and wile.

Victor Mair said,

December 23, 2013 @ 6:32 pm

@Dan Lufkin and others

In light of the conversation we're having over here ("Cantonese as Mother Tongue, with a note on Norwegian Bokmål",

which several times mentions Old Norse, I'm deeply impressed by the importance of Old Norse in far more ways than I previously was.

Seonachan said,

December 23, 2013 @ 8:42 pm

@maidhc Actually sprèidh can mean dowry in Scottish Gaelic. Dwelly gives 4 definitions: "1. cattle of any kind; 2. sheep; 3. livestock; 4. marriage portion of cattle."

Furthermore, there is a popular song called "Mo Nighean Donn nam Meall-Shùilean" (My brown-haired maiden of the beguiling eyes) that has this very meaning of sprèidh in its refrain:

Nam faighinn thu le òrdugh clèir

Chan iarrainn sprèidh no fearann leat.

[If I could get you with a clergyman's rite

I wouldn't need a dowry of cattle or land from you]

Granted, one could also interpret this simply as "I wouldn't need cattle or land [if only I were] with you", but it's always been interpreted as dowry as far as I know.

link to sound file with notes:

http://www.tobarandualchais.co.uk/fullrecord/99728/1

link to text:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/alba/oran/orain/mo_nighean_donn_nam_meall_shuilean/

Seonachan said,

December 23, 2013 @ 8:50 pm

The first link I posted (with the sound file) gives the notes in Gaelic; here's the English version:

http://www.tobarandualchais.co.uk/en/fullrecord/99728/1

Victor Mair said,

January 2, 2014 @ 8:34 am

The Irish form is explained in the Lexique étymologique de l'irlandais ancien (the only real and unfinished etymological dictionary of early Irish) as a variant of preid < Latin praeda.

Victor Mair said,

January 2, 2014 @ 10:37 am

From Brendan O'Kane:

Interesting! And probably not surprising — there’s a ton of Latin vocabulary in Irish, as well as more recent loans. The most(?) common word for “boy” in the Donegal dialect of Irish that my father speaks is “gasúr,” from Anglo-Norman “garsun,” which is related to the modern French “garçon.”

My favorite product of the intersection between Irish and Church Latin is the 9th-century “Pangur Bán” (“White Fuller”) — a poem written by a monk (in the margin of a copy of St. Paul’s Epistles) about his life with his cat. Robin Flowers’ translation is pretty hard to beat:

I and Pangur Bán, my cat

'Tis a like task we are at;

Hunting mice is his delight

Hunting words I sit all night.

Better far than praise of men

'Tis to sit with book and pen;

Pangur bears me no ill will,

He too plies his simple skill.

'Tis a merry thing to see

At our tasks how glad are we,

When at home we sit and find

Entertainment to our mind.

Oftentimes a mouse will stray

In the hero Pangur's way:

Oftentimes my keen thought set

Takes a meaning in its net.

'Gainst the wall he sets his eye

Full and fierce and sharp and sly;

'Gainst the wall of knowledge I

All my little wisdom try.

When a mouse darts from its den,

O how glad is Pangur then!

O what gladness do I prove

When I solve the doubts I love!

So in peace our tasks we ply,

Pangur Bán, my cat, and I;

In our arts we find our bliss,

I have mine and he has his.

Practice every day has made

Pangur perfect in his trade;

I get wisdom day and night

Turning darkness into light.

(Original plus literal gloss at http://www.asnc.cam.ac.uk/spokenword/i_pangur.php?d=tt.)

My cat back in Beijing is named after the poem’s protagonist — Pangur Breac (“stripey Pangur”), since she’s a tabby — though I mostly call her 胖胖 or “Lunchbox” these days on account of her prodigious laziness and obesity. Not a huntress, and neither street-smart nor book-smart, but a very affectionate girl all the same. She kept me company on a lot of late-night translation sprees.

Victor Mair said,

January 3, 2014 @ 10:18 am

From the marine whom I mentioned in the original "Kimchee" post (http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=9336):

=========

I read this LL entry through to the end; nice poem there by the monk.

I recently read Stephen Greenblatt's Will in the World, and then watched two memorable period films, Mary Queen of Scots and Anne of a Thousand Days, both now nearly 45 years old. Glenda Jackson remains the best film Queen Elizabeth, and Burton the best Henry VIII.

Cattle raiding was a way of life, with regular cross-border raids that often included low-level military skirmishes. These "raids" included large military forces and the raiders could bring a thousand or more cattle across the border.

After one series of insults the Scots advanced into England on 24 November, 1542, with an army of 15,000 men. According to accounts of the battle, the Scots failed to acknowledge a command structure for the battle, and were routed by an English force of 3,000.

In the resulting debacle hundreds of Scots drowned in the marshes along River Esk and the remainder were captured. 1200 nobles were taken to London as captives of Henry VIII. The remaining solders were sent home, wearing nothing but their shirts; many of them perished of exposure on the way home.

James V, who was not present at the battle, withdrew to Falkland Palace where he died of two weeks later at the age of 30, leaving behind a 6-day old daughter, Mary Queen of Scots.

per incuriam said,

January 3, 2014 @ 11:53 am

The Irish form is explained in the Lexique étymologique de l'irlandais ancien (the only real and unfinished etymological dictionary of early Irish) as a variant of preid from Latin praeda

……

Murray specifically refers to spreidh as "livestock plunder" and discusses it in the context of the great Táin Bó Cúailnge cycle on cattle raiding, which has already been mentioned in the above comments

It seems surprising they should have borrowed the word if all this was indeed such an ancient tradition…

Táin Bó Cúailnge is not actually about a "cattle raid" in any sense in which that expression would normally be understood. The casus belli happens to be a particular bull which the queen craves in order for her various possessions to match exactly those of her husband. She initially arranges to rent it from its owner, on generous terms, and it is only when that agreement breaks down that force is resorted to. There follows a major military expedition to seize the bull, with hostilities conducted largely by way of single combat. There is precious little of "cattle-raiding", as far as I can see.

Also, in response to another comment above, while the Tain is undoubtedly the great Irish epic it can hardly be described as a "core canonical text". It has come down to us not as a single text but as various recensions, from different periods, none of them canonical.

And virtually none of the action takes place in "Ulster" in the modern sense. The Cooley area passed to Leinster many centuries ago, before the Ulster plantations, so it has no "Scotch-Irish" connection. In fact it appears to have been within the English Pale.