The degendering of the third person pronoun in Mandarin

« previous post | next post »

One of the first things a student learns when studying Mandarin is the third person pronoun, tā. This was originally written 他 (with "human" radical), and it stood for feminine, masculine, and neuter — "he", "she", and "it". During the early 20th century, however, some bright folks — undoubtedly in emulation of European languages — thought it would be a good idea to introduce gender into the Chinese writing system, so 她 (with "female" radical) came to be used for the feminine and 它 (with "roof" radical) for the neuter. I always thought that rather odd, because no attempt was made to differentiate the three forms in speech, only in writing, hence 他, 她, and 它 were still all pronounced tā.

Well, it's not quite right to say that no attempt was made to differentiate the three forms in pronunciation, since there was a half-hearted effort to introduce yī for feminine and tuō for neuter, but it didn't catch on.

Beyond 他, 她, and 它, there are also 牠 (with "bovine" radical) for animals and 祂 (with "spirit" radical) for deities, etc. All of these were — and still are — pronounced tā.

In recent years, however, there has been an attempt to get rid of the gender distinctions for the third person pronoun and go back to a genderless stage. What is most curious, though, is the manner in which this is being done, namely, through Pinyin. Instead of 他, 她, 它, 牠, and 祂 — all pronounced tā — these are now being replaced by none other than "ta"!

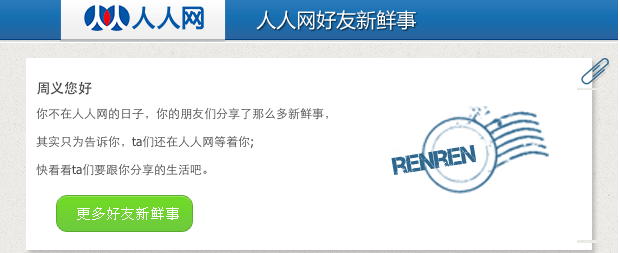

As a specimen of how this is being done, let us look at this interesting notification from Rénrén wǎng 人人网 ("Renren Network" [rénrén means "everybody"]). Rénrén wǎng 人人网 ("Renren Network") is one of a few Chinese Facebook clones which have been more or less popular with younger Chinese.

Here is a screen shot of the notification from Renren:

The pronoun "ta" (actually the plural "ta们" ["they"]), referring to your friends, occurs twice. Here's the first instance: ta men hái zài Rénrén wǎng děngzhe nǐ / ta们还在人人网等着你 ("they're still waiting for you on Renren").

The same usage was also in the subject line of the e-mail from Renren with the following formula:

X, nǐ de hǎoyou Y, Z hé nǐ fēnxiǎngle tamen de shēnghuó, kuài qù kànkàn ba / X, 你的好友Y、Z和你分享了ta们的生活,快去看看吧

("X, your good friends Y and Z have shared their life with you, hurry up and take a look").

In Taiwan, the gendered nǐ 你 ("you") (e.g., 妳) is also in evidence.

In any case, it is noteworthy that some native speakers feel the need to resort to using Pinyin in order to avoid indicating gender. My guess is that they do so, instead of simply junking all the concocted gendered forms of the second and third person pronouns and just going back to genderless tā 他 ("he, she, it") and nǐ 你 ("you"), because the characters seem somehow to be palpable and eternal. Once they come into existence, it is hard ever to let go of them. This is why dictionary makers and font designers have to contend with tens of thousands of characters, even though the vast majority are completely obsolete.

One final observation: once again, this switch from 他 and 她 to "ta" mirrors / emulates the collapsing of "he" and "she" into "they" in English, about which so much has been written on Language Log.

[Thanks to Eric Pelzl]

Carl said,

December 13, 2013 @ 12:02 am

Of possible interest, the parallel effort to introduce a gendered pronoun into Japanese succeeded, more or less.

In classical Japanese, 彼 kare was gender neutral. To translate Western novels, the circumlocution 彼女 kano jo (literally, "this female") was introduced.

Today, kare is pretty much exclusively male. However, for the most part, Japanese speakers avoid the use of pronouns and prefer to either use the person's name or just omit the subject from a sentence when it can be inferred from context. (In the English sentence, "he gave him it," how much work do the pronouns actually do? You have to know from context who the two men are and what it was the one gave the other.) When kare and kanojo (now one word, conceptually) are used, it's often used to mean "boyfriend" or "girlfriend." (Again, seems strange to English speakers, but then we say, "She's his girl," and the like.)

Steve Kass said,

December 13, 2013 @ 12:38 am

Wow. It seems like this "Ta" is all over the place.

Here are three examples of Ta们 from the website of the official state news agency, Xinhua. If I'm not mistaken, the first one refers to actors and actresses, the second to restaurants (If so, will Ta们 begin to replace 它们?), and the third, perhaps least surprisingly and/or most helpfully, to transsexuals.

http://news.xinhuanet.com/fashion/2013-11/15/c_125666667.htm

http://news.xinhuanet.com/food/2013-05/14/c_124706628.htm

http://news.xinhuanet.com/society/2010-06/04/c_12180061.htm

Googling for "ta们," it looks like Ta and TA might both be more common ways to write the word than "ta," which fits other Latin-letter uses in Chinese, like QQ and T恤衫. I'm curious to know if a native speaker/reader who grew up with Pinyin would think of this as Pinyin.

Google Translate consistently puts Ta into its translation of anything containing "Ta." Ta们 need to catch up with this trend!

Simon P said,

December 13, 2013 @ 1:19 am

Cantonese never intruduced the gendered pronouns, of course, and still uses 佢 (keoi5) for "he", "she" and "it". What about Taiwanese?

Simon P said,

December 13, 2013 @ 1:21 am

Also, it's funny that it's been going the other way in many Western languages, such as Swedish, where the gender-neutral pronoun "hen" has been gaining ground in later years.

jfruh said,

December 13, 2013 @ 1:33 am

My girlfriend in college's father was ethnically Chinese from the Philipines — I think his native language was either Cantonese or Hokkien? Anyway, he definitely had problems with gendered third person pronouns, and would routinely refer to people, animals, and things (in English) as "it."

Jason said,

December 13, 2013 @ 1:33 am

"He gave him it" sounds like an absolute blasphemy to me. "He gave it to him," however, is much easier to disambiguate.

English has many rules which have exceptions when it comes to pronouns. For example, the particles found in phrasal verbs can often either precede or follow the complement of the verb ("He knocked out the boxer" –> "He knocked the boxer out"), but they can only follow a pronoun ("He knocked her out" vs. *"He knocked out her").

When using a series of object pronouns, word order is too simple; most native speakers draft a preposition to help out.

This is completely different from, say, "she's his girl," where there is only one pronoun co-indexed with with the noun ('his' isn't a pronoun; it's a possessive adjective).

Matt_M said,

December 13, 2013 @ 2:20 am

@Jason: Blasphemy? Really? "He gave him it" struck me as just a little odd. I am often puzzled by the way in which small differences between dialects are so often referred to in terms that evoke moralistic outrage.

David Morris said,

December 13, 2013 @ 6:08 am

My Chinese ESL students very often refer to their mother as 'he' or boyfriend as 'she'. Very recently my colleague and I were discussing a problematic student with our academic manager, a Chinese woman of long residence in Australia, and she referred to him as 'she'.

Victor Mair said,

December 13, 2013 @ 6:22 am

@David Morris

That strikes a poignant chord with me. I have Chinese friends who have been in the United States for 40 years or more and still cannot distinguish between "she" and "he".

Craig said,

December 13, 2013 @ 9:35 am

@Victor Mair, @David Morris

My boss's default is actually to call everyone "she", which on any given day can still throw me off when she refers to male colleagues, but usually gets a small smile at its subversion of the patriarchy. Or at least that my reaction that it falls on the spectrum of funny to strange to degender "she" might mirror a similar strangeness for some speakers with "he". If only we had a good singular "they" for even when the gender is known or could be deduced by both speakers.

Coby Lubliner said,

December 13, 2013 @ 9:35 am

Turkish is another language with a genderless 3rd-person plural (o), and therefore it never surprises me when Turks have trouble with English he and she. What always has surprised me is that Italians often have the same problem, what with egli/lui/esso and ella/lei/essa. Could it be too much of a good thing?

un malpaso said,

December 13, 2013 @ 10:12 am

Georgian also has the genderless pronoun… ის (is), and my friends in Georgia often had the same issue… using English "he" for everything in most situations.

Levantine said,

December 13, 2013 @ 10:54 am

"He gave him it" is pretty unremarkable to me, and I can imagine various contexts in which I might hear it said, or say it myself (I'm a BrE speaker from London). If I'm not mistaken, the archaic "he gave it him" survives in Northern English dialects.

Alexander said,

December 13, 2013 @ 11:28 am

I wonder, could it be that Mandarin speakers who learned to read in childhood, as a function of their early literacy, actually have two (or three) homophonous 3s pronouns in their idiolect, differing in this way from the idiolects of non-literate speakers? I have always assumed the gendered spellings, even today, had the same purely orthographic status they did when introduced. But do at least some speakers today actually have more than one 3s pronoun?

Go for aesthetic appeal said,

December 13, 2013 @ 11:53 am

Victor Mair said,

December 13, 2013 @ 6:22 am

@David Morris

That strikes a poignant chord with me. I have Chinese friends who have been in the United States for 40 years or more and still cannot distinguish between "she" and "he".

I came across a comment about window close for making an intuitive differentiation between the two if the exposure comes after a certain young age.

Ran Ari-Gur said,

December 13, 2013 @ 2:16 pm

> In any case, it is noteworthy that some native speakers feel the need to resort to using Pinyin in order to avoid indicating gender. My guess is that they do so, instead of simply junking all the concocted gendered forms of the second and third person pronouns and just going back to genderless tā 他 ("he, she, it") and nǐ 你 ("you"), because the characters seem somehow to be palpable and eternal.

Do these speakers recognize that 他 and 你 are supposed to be "genderless"? I mean, if they've been masculine-specific since the early twentieth century, it seems hard to just start using them generically again, since it could seem like you're excluding women rather than being gender neutral.

(It sounds a little bit like how "man", which was gender-neutral in Old English, is now absolutely masculine — at least when it's a count noun — such that terms like "fireman" and "policeman" are non-gender-neutral and required coinages like "firefighter" and "police officer". Of course, in English it was an actual linguistic change, rather than just a spelling change, and happened much much longer ago, so has had more time to become fixed. So it's obviously quite possible that the process is more reversible in Mandarin.)

Eric P Smith said,

December 13, 2013 @ 6:05 pm

Here's another BrE speaker for whom "He gave him it" is normal.

Sara Scharf said,

December 13, 2013 @ 7:01 pm

"What always has surprised me is that Italians often have the same problem, what with egli/lui/esso and ella/lei/essa. Could it be too much of a good thing?"

I have never found Italians or French people to make these mistakes *except* when using possessives when different genders are involved, e.g. "her father" often comes out as "his dad" because in Italian it's "il suo babbo," and in French, "son papa," etc.

stanbot said,

December 13, 2013 @ 7:19 pm

Ta would be an excellent word to borrow for a degendered 3rd person pronoun in English. I remember reading something about kids in Baltimore using "yo", but "ta" has a better ring to it.

David Morris said,

December 13, 2013 @ 8:12 pm

Another pattern I notice from Chinese students is 'she's' and 'he's' as possessives: 'she's book' or 'he's computer'. It kind of makes sense grammatically ('Mark has a book > it is Mark's book' : 'She has a book > it is she's book') and it is certainly understandable pragmatically.

Dave Cragin said,

December 13, 2013 @ 10:24 pm

In her book, Dreaming in Chinese, Deborah Fallows offers a few perspectives on why it is common for Chinese to mix up he & she (as Victor noted).

One is a different angle on the concepts offered by Alexander, i.e., a Chinese speaker doesn't make the distinction between he/she until they start to write. By this time, the idea of a gender neutral pronoun is well established as part of the thinking process.

A 2nd idea of Fallows’ is that: “Pronouns just aren’t that important to Chinese, and they omit them frequently. A good rule of thumb for Chinese would be: unless you really need to use the pronoun to clarify the context, or highlight the antecedent pronouns, or otherwise draw attention in some way, just leave them out.”

She noted when learning Chinese, she used pronouns too frequently. I likely do too: I asked friends about how to complement a speaker on their talk and most said "speech was very interesting" 演讲很有意思。" (yanjiang you yisi). However, as an English speaker, I wanted to add "your", i.e., "your speech was very interesting 你的演讲很有意思。(Ni de yanjiang you yisi).

Other opinions on this by those who know both Mandarin & English would be of interest…..

Bryan said,

December 13, 2013 @ 11:40 pm

In lecturing about Chinese (in my introductory course on Chinese literature and culture), I sometimes remark on the irony of the fact that while we struggle in English to find gender-neutral ways of expressing ourselves (including awkward expressions such as "he or she" and "him or her"), Chinese speakers have gone out of their way to introduce the pronominal distinctions we now find so problematic! Apparently things are starting to come full circle.

Brian Spooner said,

December 14, 2013 @ 9:40 am

I found this very interesting. But I have a somewhat different take on it: I think it is another case of the way language use has been changing everywhere over the past century as literacy has gradually become universal (instead of the badge of a small literate class), and the primacy of the written language over the spoken has declined. People no longer see the written language as some sort of model for speaking, but vice versa. The same thing is happening in every language with any record of literacy. It just works differently in each language. (So far as I know Persians have never felt the need to distinguish gender in either speech or writing, even though they work with Arabic, which does; in their poetry I think they have always prefered the ambiguity.) Of course, this is essentially what I was saying in the long introductory essay in the book Bill Hanaway and I published last year (Literacy in the Persianate World) with a chapter by you. But I think it's time something more detailed was written about it. It's historically very important, because written language had another function: it standardised communication. Spoken language is therefore now losing its standards–with all sorts of fascinating implications for what is happening generally to linguistic communication in the current century.

Levantine said,

December 14, 2013 @ 11:55 am

Why would the fact that Persian uses (a variant of) the Arabic script have led its speakers to adopt Arabic linguistic gender anyway? Turkish, which was likewise once written in an Arabic-derived script, also lacks any sort of grammatical gender, and I don't think it has anything to do with a penchant for poetic ambiguity.

Victor Mair said,

December 14, 2013 @ 1:51 pm

@Levantine

Professor Spooner said "work with Arabic", which means a lot more (e.g., grammar, morphology, lexicon, etc.) than just adopt the Arabic script. He knows what he's talking about.

Brian Spooner said,

December 14, 2013 @ 2:12 pm

Actually, what is interesting is that the relationship between Persian and Arabic has been mainly between the written languages (relating to the study of the Qur'an), and the relationship between Persian and Turkish is entirely between the spoken (vernacular) languages (except within the Ottoman empire several centuries ago). Persian and Turkish/Turkic vernaculars continue to coexist from western Iran through northern Afghanistan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, as the dominant languages within an interesting Sprachbund, in which gender neutrality is standard.

Levantine said,

December 14, 2013 @ 4:45 pm

With all due respect, Professor Mair, Persian grammar has remaine largely unaffected by Arabic. The lexicon, of course, is another matter.

Brian Spooner said,

December 14, 2013 @ 5:26 pm

I suppose it depends to some extent on how you draw the line between grammar and syntax. There is as much Arabic in Persian as Latin and Greek in English, and Arabic grammar (including the gender distinction) is maintained in the Arabic words used in Persian. However, as with English, the amount of Arabic in Persian speech varies with register.

Victor Mair said,

December 14, 2013 @ 10:46 pm

From an American colleague who taught in Australia for about a decade:

I’m interested that collapsing of “he” and “she” into “they” has had “so much written” about it on Language Log. [VHM: see below for archives] Sorry I’ve missed that thread. Could you refer me to a particularly representative example of the discussion? I was stunned to encounter this first when we moved to Australia in 1996, where it was already well established; somehow I had avoided it before that time, while living in the States. I confess I’m not reconciled to the usage and always try to avoid using it, one way or another. But then I also criticize my daughter when she misuses the case of a pronoun, as in “You gave it to Mommy and I”, or the reverse, like “Her and I went to town today”; the first is more common, I think, but the other is also often heard, usually by much imitated celebrities on tv. I have seen tv footage of Prince Charles using it, and I think also of QE II using it. So it’s “royal English” now.

http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?category_name=singular-they

Chau Wu said,

December 14, 2013 @ 10:54 pm

@ Simon P.

In Taiwanese, the third person pronoun is "i" 伊, pronounced [ee]. It is gender-neutral, used for he/him, she/her, and they/them. 伊 is almost never used for animals or inanimate objects. The British missionary Rev. Thomas Barclay translated the Bible into Taiwanese in 1933. In this version we find lots of places which are grammatically correct in English but sound very strange in Taiwanese. Thus, Luke 17:31, "On that day, let him who is on the housetop, with his goods in the house, not come down to take them away…" The "them" in the last phrase "not come down to take them away" is translated as 伊 (莫得落來提伊 bóh-tit lóh-lâi théh i…). It sounds very confusing to Taiwanese readers: Is there another person in the house?

Owing to the gender-neutral 伊, some of my Taiwanese friends who have lived in the US for over 50 years still have trouble telling "he" and "she" apart in English.

reader_not_academe said,

December 15, 2013 @ 6:06 am

i'm coming from hungarian, another language with no grammatical gender and a strong tendency to drop pronouns, and for the past 10+ years i've been working in an environment where english is the main working language for a mix of native and ESL speakers. the occasional "slip of the tongue" on the hungarian speakers' side, confusing he and she, is such a well-established fact of life that it gets noticed but no longer commented on at all.

one similar thing that still throws me off on a daily basis is how in german grammatical gender overrides human gender. "das mädchen" for a girl is neuter, and referring to a girl with "es" (it) is something i've gotten used to, but using "sein" (its) instead of "ihr" (her) in the possessive still requires genuine mental effort every time i hear it or must produce it – particularly because "sein" (its) coincides with the masculine possessive "sein" (his).

but for me the most troubling aspect of this has to do with the whole "does language define one's thinking" discourse. when people come up with infographics about how speakers of languages with strong future-time-reference tend to save more (or be more hedonistic, i forget), it's relatively easy to dismiss that. but then you come to proper controlled experiments in which speakers of polish, whose lexicon distinguishes warm and cold blue, can tell the two shades apart with more ease than speakers of, say, english. do polish speakers have a different conceptual breakup of the color spectrum? apparently so. do they "see" the world in a different way? head-scratching in response to a question that has no refutable answer. and now, obviously, he vs. she. all the evidence in the discussion so far is purely anecdotal, but i'm convinced one can construct cunning experiments where responses from one group are primed or otherwise affected by their language's grammatical gender, while responses from another group are not. in fact, i'm pretty sure those experiments have been done. can anyone cite references?

Victor Mair said,

December 15, 2013 @ 8:06 am

@reader_not_academe

Thank you very much for your valuable comments on Hungarian and other languages.

However, we need to do a little unpacking of what you write here:

=====

but for me the most troubling aspect of this has to do with the whole "does language define one's thinking" discourse. when people come up with infographics about how speakers of languages with strong future-time-reference tend to save more (or be more hedonistic, i forget), it's relatively easy to dismiss that.

=====

Actually, it makes common sense to assume that speakers of languages with strong future-time-reference tend to save more, etc. I think, though, that you may be referring to Keith Chen's widely hyped theory about the supposed superiority (in terms of saving, health, etc.) of languages that are said to lack grammatical future, which is just the opposite of the common sense assumption. (My purpose here is not at all to support the latter claim.)

It's unfortunate that people continue to cite Keith Chen's arguments, since they have been thoroughly discredited (in terms of empirical data, linguistic description, and other criteria) in this very long Language Log comment and elsewhere (see links embedded therein):

http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=6821#comment-424777

The third paragraph from the bottom of that comment reads:

=====

I submit that, while Chen's methodology may be elegant, his conclusions are bunkum and not at all a good test of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. I was going to call his proposals "voodoo economics" or "zombie economics", but I found that those expressions have already been used to designate different kinds of economic fallacies, so I refer to Chen's variety as "mumbo-jumbo economics" instead.

=====

See also:

http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=6821#comment-425752

http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=6821#comment-426751

http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=6821#comment-428242

http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=6821#comment-426082

http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=6821#comment-426220

http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=6821#comment-426431

and other comments to the same post.

Chau Wu said,

December 15, 2013 @ 9:23 am

Correction of my previous comment: "In Taiwanese, the third person pronoun is "i" 伊, pronounced [ee]. It is gender-neutral, used for he/him, she/her, and they/them."

The third person plural pronoun in Taiwanese is "in" (which has no corresponding Chinese character). The singular "i" 伊 is used for plural only rarely, such as in set phrases "bô i hoat" 無伊法 'cannot deal with him/her/them'.

Victor Mair said,

December 15, 2013 @ 12:31 pm

N.B., in the previous comment by Chau Wu: "The third person plural pronoun in Taiwanese is "in" (which has no corresponding Chinese character)." Another of the many common (and uncommon) morphemes in Taiwanese and other Sinitic languages that lack a corresponding Chinese character.

Sid said,

December 15, 2013 @ 4:02 pm

reader_not_academe said:

In my experience German speakers aren't really strict about it. From what I have heard being used, the neuter forms are only mandatory for the articles and relative pronouns.

– ein Mädchen, das…

– *ein Mädchen, die…

– ****eine Mädchen

For personal and possessive pronouns I hear the feminine forms more often than the neuter ones, with the probability of it being neuter becoming higher the closer it is to the noun.

– unremarkable: Wir sahen ein Mädchen mit einer Handvoll Füllwörter um Abstand zum Pronomen zu schaffen. Sie hatte auch…

– […] Es hatte auch…

– ein Mädchen und ihre…

– ein Mädchen und seine…

Sid said,

December 15, 2013 @ 4:05 pm

Sorry, hit submit too fast. The last few lines were supposed to read:

– unremarkable: Wir sahen ein Mädchen mit einer Handvoll Füllwörter um Abstand zum Pronomen zu schaffen. Sie hatte auch…

– rare: […] Es hatte auch…

– both are equivalent: ein Mädchen und ihre…

– or: ein Mädchen und seine…

hanmeng said,

December 17, 2013 @ 4:14 am

I have witnessed conversations in Mandarin where someone is talking about a third party unknown to the listener, so at some point the latter asks if the unknown party is male or female. (Astonishingly, they don't ask if they're deities or animals!) So I guess even if you don't have a word for it, you can still grasp the concept.