Atlas of True(?) Names

« previous post | next post »

As reported by Der Spiegel and picked up by the New York Times blog The Lede, two German cartographers have created The Atlas of True Names, which substitutes place names around the world with glosses based on their etymological roots. It's a very clever idea, but in execution it enshrines some questionable notions of "truth."

The cartographers, Stephan Hormes and his wife Silke Peust, say they were inspired by J.R.R. Tolkien's maps of Middle Earth, which include names like "Dead Marshes" and "Mount Doom." So they've filled their world maps with similarly descriptive toponyms. "We wanted to let the Earth tells its own story," Stephan Hormes told Der Spiegel. "The names give you an insight into what the people saw when they first looked at a place, almost with the eyes of children. Through the maps, we wanted to show what they saw."

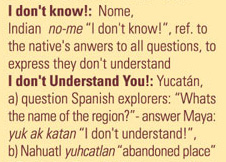

From a brief examination of the "true" names given on the maps, it appears that the cartographers have accepted a good number of disputed derivations and folk etymologies. Some of the popular etymologies are quite persistent. For instance, there's the old story about Yucatán meaning "I don't understand (you)," which goes back to early Spanish sources. The Wikipedia page on the conquistador Francisco Hernández de Córdoba (Spanish, English) traces it back to Fray Toribio de Benavente Motolinia's Historia de los indios de la Nueva España (History of the Indians of New Spain, c. 1541). There are plenty of competing theories, such as Bishop Diego de Landa's story that it's a Hispanicized version of Ci uthan, meaning "they say it." Or perhaps it's from Nahuatl Yokatlan "place of riches" (disputed here), or from a word meaning "massacre" (from yuka "to kill" and yeta "many" — so says Adrian Room's Place Names of the World). Even Hormes and Peust give another possibility: Nahuatl yuhcatlan "abandoned place" (see discussion in this report by David & Alejandra Bolles, who throw a few more potential origins on the fire).

Similarly, the story that the name of the Alaskan town of Nome comes from a phrase meaning "I don't know" (ki-no-me) goes back to 1905 at least. A 1901 letter by George Davidson (recently noted here by Jon Weinberg) provides another popular theory, that the map notation ? Name was misread as C. Nome (for Cape Nome). (The Nome Convention and Visitor Bureau accepts this derivation.) Wikipedians suggest that Nome could actually have been named after a similar Scandinavian toponym, but I don't know how plausible that is.

The Nome = "I don't know" and Yucatán = "I don't understand you" stories are replicated by other popular etymologies that tell of miscommunications between European explorers and indigenous people. Kangaroo is another one, as discussed by Cecil Adams in his column "The Straight Dope." After discovering the parallels between the supposed derivations of kangaroo, Yucatán, and Nome, Adams writes: "Having now had the 'I don't know' yarn turn up in three different parts of the globe, I can draw one of two conclusions: either explorers are incredible saps, or somebody's been pulling our leg."

Some of the etymological glosses given in The Atlas of True Names are misleading in other ways. "New York" is given as "New Wild Boar Village." That's based on the idea that York in England derives from Old English eofor "wild boar" + Latin vicus village. But the Anglo-Saxon name Eoferwic was evidently a folk etymology of sorts, reinterpreting the earlier toponym Eboracum, a Latinization of Celtic Eborakon, said to mean "place of yew trees." So should the "true" name of (New) York relate to boars or yews?

Amazon is given as "The Boat Destroyer," although it's usually said that Francisco de Orellana named the river for the mythical Greek tribe of Amazons after a 1541 battle with local female warriors (or perhaps male warriors whom Orellana mistook to be female). Granted, some take this to be a folk etymology, perhaps a corruption of a Tupi or Guarani word for "wave." The conjecture that it originally came from a native word amassona meaning "boat destroyer" is given by various old sources, but this was disputed as early as 1857 by Daniel P. Kidder and James C. Fletcher in Brazil and the Brazilians. (They say the derivation "has no foundation whatsoever.")

Other examples are more mysterious. Nicaragua means "Here are People"? Many sources say there was a lake the Spanish called Nicaraoagua after a local chieftain named Nicarao combined with agua "water." Regardless, you'd think agua has to figure in there somewhere (Wikipedia suggests "surrounded by water"), so I have no idea where the "people" might come in. [Update: Looking at the website again, I see they explain this as Nahuatl nican "here" + arahuac "people".]

I'm sure Language Log readers could come up with any number of additional problematic names in the atlas. But there's a more fundamental flaw to this project. Calling these glosses "true names" is nothing more than the etymological fallacy on a grand geographic scale. Does rendering New York as "New Wild Boar Village" really tell you "what the people saw when they first looked at a place, almost with the eyes of children"? Or how about Vancouver rendered as "From the Cowford"? (Vancouver was named after George Vancouver, whose name is from Dutch van Coevorden, denoting someone from the town of Coevorden, lit. "cow-ford.")

Even when the toponyms are more descriptive, rather than relating to the settlers' origins, the names are hardly pure and childlike. In many parts of the world, place names actually tell messy narratives of colonial encounters or other cultural contact situations. Wiping away all that history might make the world seem more like Tolkien's Middle Earth, but it doesn't tell us anything "true." The makers of the atlas say it "restores an element of enchantment to the world" — sorry, call me disenchanted.

[Update #1: On her MSNBC show, Rachel Maddow reported on the atlas — video is here, starting about 3 minutes in. She was quite taken with the Yucatán story, commenting, "If ever there was a more perfect summary of colonialism, I do not know of it." A little too perfect, I'd say.]

[Update #2: Stephan Hormes writes in to say that he included numerous caveats in the introduction to the atlas:

Not all translations are definitive. The reader may be offered a number of possible alternatives, or the translation may be prefixed by ‘probably’ or ‘presumably’.

The atlas shouldn't replace a scientific work about etymology, it is meant as an invitation to the people to start looking at the world through fresh eyes.

If you're looking for mistakes, you'll always find some, even in ordnance survey maps. There's a saying in German whether you look if the glass is half full or half emptied. I think we have approximately 80% of true names, 20% are disputed or still remain unknown.

Just take the Atlas of True Names as an idea to visualise the world of etymology to a broad audience at a glance. And these people haven't seen such a world before.

Of course, none of those caveats were picked up by the media accounts that I was going by. My apologies for coming down a bit too hard on a work that was never intended to be scholarly. In a more charitable post, Languagehat treats the atlas more in the spirit of fun in which it was presented.]

Mark said,

November 22, 2008 @ 4:17 am

Where does the kangaroo story from Cecil Adams come from?

I thought that everyone knew that this was a (pretty un-mangled) loan from Guugu Yimidhirr ganguru 'large black wallaby species'? Even if you're not spreading the myth yourself, the fact that we have (a) a perfect match for the sounds, (b) a modern language attesting the form, and (c) 100s of local languages in which kang-oo-roo (as it was recorded) would mean nothing surely is enough that we can not with any dignity say that "the actual aboriginal words for the marsupial in question sound nothing like "kangaroo,"" (Cecil Adams).

Granted, you cite this as a popular etymology, but it's so glaringly disprovable that to not do so is to spread the myth further.

Matthew Stuckwisch said,

November 22, 2008 @ 5:49 am

Perhaps an Atlas like this would be better represented in the on-line or electronic medium, where all the details could be presented. That is, you click on Vancouver and it says:

Direct Source: George Vancouver

Source Etymology: the Dutch surname van Coevorden meaning "from Coevorden"; Coeorden meaning "cow-ford"

That way everybody could decide at which level the truth is there, but also it could allow for providing competing theories as to the origin of names.

j said,

November 22, 2008 @ 7:39 am

Sounds fun, but very unreliable.

Most places around the world have been (re-)named by the European superpowers of the C&-16&17. And we have a notoriously bad ear for anything that sounds strange.

Post revolution in France, map makers were sent round to check spelling of place names, and had a horrendous time of it down Sarf, to the extent that lots of places have 2 or even 3 names on the welcome sign.

dchamil said,

November 22, 2008 @ 10:48 am

Often encountered in place names are pleonasms, names which are the same thing rendered in two different languages. An example is the River Avon — "afon" is Welsh for "river."

Benjamin Zimmer said,

November 22, 2008 @ 10:54 am

Mark: Sorry not to have rejected the kangaroo myth more forcefully. For more on its disprovability, see the alt.usage.english FAQ.

Blake Stacey said,

November 22, 2008 @ 11:20 am

Along similar lines:

In the introduction to his short-story collection Fragile Things, Neil Gaiman reports hearing an anecdote that yeti means "That thing over there." Thus:

"Oh, brave Sherpa guide, what is that animal?"

"Yeti."

"I see."

(Wikipedia has five footnotes attesting that yeti is derived from Tibetan words for "rocky place" and "bear".)

John Ross said,

November 22, 2008 @ 11:29 am

The timing suggests these books have been launched in time for Christmas – stocking fillers for etymologists, perhaps. Truthful or not, they look fun, and I can think of one or two people who might be amused to be given one, so I think I may well be a buyer.

Karen said,

November 22, 2008 @ 11:36 am

This is risible when it comes to toponyms named after people or other places. Even if York means "Wild Boar Village", the people who named New York (a) didn't know, (b) didn't care, and (c) clearly meant "New Big English Not Dutch City".

Eli said,

November 22, 2008 @ 11:52 am

@Karen: Exactly. While I might accept that derivation for York itself, it is obvious that the notation for New York on this map should be "Place We Wanted To Name After York But Is Way Over Here In The New World".

Skullturf Q. Beavispants said,

November 22, 2008 @ 11:56 am

I appreciate all your points. One small positive thing I will say, however, about the Atlas of True Names is that it forces one to look at familiar names in a new light. I'm speaking specifically of place names that weren't "translated" by the makers of the Atlas, such as Oakland, Salt Lake City, Newfoundland, and Oxford. Reading these made me have thoughts like, "Oh, yeah! Oak-Land!" I felt a little bit like Monty Python's Mr. Smoketoomuch when somebody points out to him for the first time why his name is amusing.

Andrew said,

November 22, 2008 @ 12:18 pm

I'm not sure that the authors should be read as claiming that these are 'true names' in the real world. In the light of the Tolkien references, I think this could be seen as an allusion to the fantasy trope acording to which things have 'true names' which reveal their nature, and knowledge of which gives people magical power over the bearer. The sense might be that if places in our world had 'true names' in this sense, this is what they would be.

Bobbie said,

November 22, 2008 @ 12:58 pm

There are plenty of place names that must have stories. For instance, Mount Misery. Blue Ball, and Double Trouble in New Jersey.

As for this whole business about the "natives" naming things or people, I recall a recent story about the number of women in a Native American village that had a "name" which actually indicated their marital status as "widow."

Nicholas Waller said,

November 22, 2008 @ 1:27 pm

Terry Pratchett has a Forest of Skund – "the only forest in the whole universe to be called — in the local language — Your Finger You Fool, which was the literal meaning of the word Skund" – in The Light Fantastic.

@Karen: Even if York means "Wild Boar Village", the people who named New York (a) didn't know, (b) didn't care, and (c) clearly meant "New Big English Not Dutch City"

Similar with any number of US cities called Manchester or Leicester or other -chester and -cester endings … I bet the namers didn't care that there was no Roman camp originally on the site.

Sili said,

November 22, 2008 @ 1:47 pm

So Coevorden = Oxford = Hudevad. The Germanic tribes really weren't all that imaginative were they?

rpsms said,

November 22, 2008 @ 1:58 pm

I always imagined that llama was basically the spaniards calling the animal a whatchamacallit.

Any validity to this wild fantasy?

David Eddyshaw said,

November 22, 2008 @ 2:46 pm

I believe "llama" is in fact Quechua for, er, llama.

I think it's sometimes applied to that foreign animal the sheep too.

John Cowan said,

November 22, 2008 @ 3:20 pm

My guess is that it's called Atlas of True Names because of the etymology of etymology. And in order to make such a map at all, it's necessary to choose between lots of competing stories, particularly in cases where all of them are disputed. I think that picking nits misses the point.

Bloix said,

November 22, 2008 @ 3:42 pm

It's hard to understand how German cartographers could be so lighthearted about this subject.

What is amusing about Gyddanyzc-Dantzike-Danzig-Gdańsk? or Konigsberg-Kaliningrad? Or Vilnia- Wilno-Vilno-Vilna-Vilnius? Just typing that last one makes my blood run cold.

language hat said,

November 22, 2008 @ 4:42 pm

I agree with John Cowan. It's not a scholarly work of etymology, it's a fun/popular language-related stocking-stuffer, for Pete's sake, and as such, it seems to me a lot better done than most such. If people really get into the topic, they can certainly find more accurate references, but "accepts some dubious etymologies" is not exactly the same as "is a piece of crap," which seems to be the attitude here.

To Karen's point about "toponyms named after people or other places," the point is not to provide an analysis of the history of the name but to give the earliest available meaning for the name. If you don't care about that, fine, but don't blame them for not doing something they weren't trying to do.

Andrew said,

November 22, 2008 @ 5:17 pm

Actually, the name 'New York' has a more specific origin; it was named in honour of the Duke of York (later King James VII and II), who was the first proprietor of the colony. (His Scottish title was duke of Albany, which accounts for the name of the capital of New York State.)

I'm not sure this kind of altlas can easily accommodate places called after people. What does it say for Washington, for instance?

Benjamin Zimmer said,

November 22, 2008 @ 6:55 pm

Language hat: It's not a scholarly work of etymology, it's a fun/popular language-related stocking-stuffer, for Pete's sake, and as such, it seems to me a lot better done than most such.

Agreed. I guess I was reacting more to the press coverage, which does treat the atlas as scholarly. And the "true names" business set off my etymological fallacy detector, though as John Cowan points out, they're just applying the same etymologizing technique to the word etymology itself.

Assistant Village Idiot said,

November 22, 2008 @ 9:49 pm

It isn't only Germans who are unoriginal, it's all of us. Hydronyms in particular have an unfortunate preponderance of The River, Big River, Black River, Big Lake, Lake with Fish, etc when they are translated from the aboriginal's languages. Danube, Don, Dniester, Dniepr, Tyne – real geniuses our ancestors were: "We call it The River. Clever, huh?"

We do no better now. In New Jersey everyone knows where The Shore is, many states have no ambiguity when you say The Lake, or The River. You only need names when there are two of something.

Trond Engen said,

November 22, 2008 @ 11:31 pm

That Nome, Alaska, was named after the municipality (kommune) of Nome, Norway, is unlikely, especially since the latter was established in 1964 after the merger of the two former municipalities of Holla and Lunde. The new name was taken from a lake on the former municipality line.

However, I gather that Nome, Alaska, was founded (or something like that) in 1898 by the "three lucky Swedes", Erik Lindblom from Lofsdalen, Härjedalen, Jafet Lindeberg from Kvænangen in Northern Norway, of Saami or Kvæn origin, and John Brynteson from Ärtemark, Dalsland. Nome (or Nume, Numme etc.) is not uncommon as a toponym denoting small rivers and shallow lakes (and, secondary, farms) in Norway and Sweden, and I suppose there's a chance that one of the "lucky Swedes" named the spot after a place from his childhood. I haven't managed to find this toponym anywhere near the birthplace of either of them, though.

The first cartographer of Nome seems to have been a certain Gustaf Nordblom, clearly of Swedish origin, in 1899 (). There are a few Scandinavian names on the map, namely creeks carrying the surnames Balto and Lindblom and perhaps the town name Moss, all named after more likely sources than an obscure hydronym. BLR Antique Maps claims that Nordblom was a civil engineer, surely because the title C.E. is following his name on the map, but doesn't know more about him. I see that a person of the same name was in Yukon the year before as an artist at the Gold Star studio (). According to Mary Towley Swanson's Swedish–American Artists’ Index (, App. C) this Gustaf Nordblom was a portrait artist born in Varberg, Halland, Sweden in 1869. I can't find a Nome near Varberg either.

All this on the assumption that the name isn't older than the gold rush.

Nathan Myers said,

November 23, 2008 @ 1:15 am

Rooster Rock State Park on the Columbia River in Oregon is named after a rock formation that is distinctly dissimilar to any sort of poultry, but is very notably phallic. Before it became a state park it had a different, one step less euphemistic name.

Nathan Myers said,

November 23, 2008 @ 1:16 am

rpsms: A good name for a llama is "Como Se".

mollymooly said,

November 23, 2008 @ 1:47 am

I see on their Europe map, "The Channel" and "North Sea" are rendered as "The Channel" and "North Sea".

Mike Orr said,

November 23, 2008 @ 4:30 am

Been a long-time etymology enthusiast and having just read "The Secret Life of Words", I immediately bought this map and plan to put it on my wall. Regardless of whether some of the names are merely calques (literal translations of the parts of the name without regard to whether the inhabitants actually thought of them that way), it provides insight into the word roots and how things *could* be interpreted. For instance, Dublin is rendered Blackpool, which shows its similarity to the other Blackpool in England. And of course the renderings of Vancouver and New York are meant to be a joke — few at the time would have known what Vancouver or York meant.

Simon Spero said,

November 23, 2008 @ 2:10 pm

Gavagai!

Achim said,

November 24, 2008 @ 4:57 am

If there is some understanding that these maps are meant as fun rather than scholarly works of reference, there are two earlier creations that have to be named for doing better: For an international audience, Douglas Adams' "The meaning of Liff" (of which a German edition has been published). From a German point of view I would like to point out a map by the German cartoonist Gerhard Seyfried who produced a map where placenames had been substituted by (highly nonsensical, if not mildly derogatory) phonetically similar coinages. Examples: Stuttgart had become Kaputtgart, the North German town of Segeberg had become Sägewerk ("the Saw Mill"). And so on.

In general, I feel that more thorough research in the placenames rendered here would make the fun of browsing the maps more lasting. Smiling or laughing is fine, but understanding is even better. The scans available on the page do not allow to decipher the "translation" of Berlin, but it appears to be too long to be simply swamp or marsh – which is a pity as the words have their very special connotation if used to refer to the capital of Germany…

His Own Private Zydeco said,

November 24, 2008 @ 6:04 am

Evidently the name "Amazon", as applied to the warrioresses

of ancient lore, refers to the reputed practice that they kept

of excising tissue from their breasts (Gk. μαστός, PIE mazdo

or maddos, glossed as "to be fat or to flow" a la etymonline)

so as to better facilitate the proper freedom of motion which

archery requires.

This same title, given to the now world renowned river in S.

America, was meant by the first europeans to encounter it

to refer to the implacable and occluded nature of its tribut-

aries, or at least to the difficulty involved in searching out a

solitary source from which its waters draw their strength, so

to speak.

Dave H said,

November 24, 2008 @ 9:33 am

On the subject of pleonasms, Steven Brust has a marvellous example with Bengloarafurd Ford – which, when translated using the language of each wave of conquerors, becomes "Ford ford ford ford ford".

fk said,

November 24, 2008 @ 10:23 am

As a Washingtonian I am disappointed that Seattle is just Seattle. Surely the name had some meaning in (what Wikipedia informs me is) Lushootseed.

ajay said,

November 24, 2008 @ 11:24 am

Rooster Rock State Park on the Columbia River in Oregon is named after a rock formation that is distinctly dissimilar to any sort of poultry, but is very notably phallic.

As is the mountain Pob Dhiabhail – "Devil's Point" – in the Cairngorms. "Dhiabhail" means "of the Devil", but "Pob" definitely does not mean "point".

Helland said,

November 24, 2008 @ 11:56 am

'Gentle one' for Seine?? Wikipedia has 'sacred river'.

If 'gentle' is right … Celan, oh Celan.

Kevin Iga said,

November 24, 2008 @ 12:31 pm

I wonder how far back one should go in these etymologies. Proto-Indo-European?

wally said,

November 24, 2008 @ 12:39 pm

I have somewhere a map of Texas, meant to mock the English only crowd, with all the many Spanish places names rendered in English.

E.g. Yellow, the 12th biggest city in Texas.

y said,

November 24, 2008 @ 5:30 pm

After visiting Utah's Kodachrome Basin State Park, I can't help wondering what its local name must have been before it was visited by the photographers. Apparently the park and the current name were promoted by the local Chamber of Commerce.

Piers Kelly said,

November 24, 2008 @ 6:15 pm

Ben & Mark: How about a post on the folksy 'I don't know'-nyms? I've come across a few of that genre in the Philippines. I bet there's many more in the world than the three mentioned here.

Piers Kelly said,

November 24, 2008 @ 6:18 pm

Oh, and I notice Mexico City is 'Moon Navel'. Please somebody put that one out of its misery!

Benjamin Zimmer said,

November 24, 2008 @ 7:09 pm

Piers K.: Here are some more from the alt.usage.english FAQ entry on kangaroo:

Craig Daniel said,

November 24, 2008 @ 10:32 pm

Personally I think the whole thing sounds like a lot of fun, and clearly not meant seriously.

The other effort it reminds me of is the WWI map that shows the various countries as line drawings of people, formed into approximately the right shape, each as a ludicrously stereotypical caricature of people from the area depicted. The British Isles turn into a crazed kilt-wearing Scotsman brandishing a claymore, Turkey as a somewhat haughty man with a fez and a scimitar, and Gibraltar as a British bulldog.

A Reader said,

November 25, 2008 @ 12:48 pm

I find it interesting that Middle-earth is cited as an inspiration for searching for either glossing place names in English or for claiming that places should have one 'true' name. Neither of these things is particularly characteristic of Tolkien- a quick glance at the maps in any copy of The Lord of the Rings will show Erebor, Rohan, Mirkwood, Bree, Longstrand, and Khand, which put together show a wide range of etymologies (either from real world languages, Tolkien's privately developed ones, or in some cases from invented languages which were never sketched out and only appear in the odd toponym).

And places in Middle-earth are often also given multiple names, and these are not always the same meaning in different languages. Mount Doom is a good example, as its other name 'Orodruin' means roughly 'Fire Mountain'. There are also quite a few examples in Tolkien's stories of the names of places being changed for one reason or another.

All in all, Tolkien was very interested in toponyms (both in and out of his fiction), and spent rather a lot of time creating a 'realistic' suite of names for his invented world. I'm not trying to criticise the authors of this map by this, at least not much (the full extent of the effort Tolkien put into place names is really only made clear in the drafts of his stories, or by a very close examination of his maps)- the main thing that surprises me is just how strange sounding/looking most of the names in Middle-earth are. Yes, there are Mt. Dooms and Dead Marshes- there are also rather more Cirith Ungols, Gondors, Rohans, Fangorns, and Minas Tiriths (just to stick with names that feature prominently in the stories, leaving maps aside). But I suppose inspiration is inspiration, and Tolkien probably wouldn't be too unhappy to hear of someone seeing a bit more 'enchantment' in names.

Craig Daniel said,

November 25, 2008 @ 1:48 pm

Of course there's actually a major plot point about what exactly the Westron translation of "Cirith Ungol" is, and the answer is pretty darn revealing…

Julia K said,

November 25, 2008 @ 3:12 pm

Continuing on the topic of Middle-Earth place names, I immediately thought of the river that is called Baranduin by the elves and Brandywine by the hobbits. I assumed this was a simple tradition of the hobbits having misheard the Sindarin (elvish) name, but Wikipedia shows a more interesting etymology:

The name Baranduin was Sindarin for "golden-brown river". The Hobbits of the Shire originally gave it the punning name Branda-nîn, meaning "border water" in original Hobbitish Westron. This was later punned again as Bralda-hîm meaning "heady ale" (referring to the colour of its water), which Tolkien renders into English as Brandywine.

Monado in Toronto said,

November 26, 2008 @ 11:02 pm

I feel that it's more fun to look at the difference between what the cartographers and prettifiers called a place when they moved in, vs. what the pioneers called it.

For example, Regina ("Queen"), Saskatchewan, was originally called ":Pile o' Bones."

Or so I've been told.

Simon Cauchi said,

November 27, 2008 @ 12:43 am

I presume that the disputed "true names" mentioned in these posts are only a minority of the total. There must be plenty of "true names" that are quite uncontroversial. For example, Bath and its opposite numbers Baden-Baden, Aguascalientes, Waiwera, etc. (I haven't seen the book.)

Seektruthfromfacts said,

November 28, 2008 @ 5:47 pm

Good to see someone quoting Cecil Adams in an article on True Names:

"either explorers are incredible saps, or somebody's been pulling our leg."

Really? :-)

gribley said,

November 30, 2008 @ 9:52 pm

hmmph — This is fascinating and potentially a lot of fun, but I am cautious. Glancing at the map on the website, I see "United States of The Home Ruler". Perhaps that is an attempt to trace back Amerigo Vespucci's name, but it's senseless — as with the "New York" examples given above, it would make more sense to call it "United States of the Land Discovered by that guy Vespucci". It's just silly enough as to be pretty misleading, I'm afraid.

Ted said,

December 5, 2008 @ 7:13 pm

Thanks to "A Reader" for discussing Tolkien more coherently than I was going to. I'd just add that Tolkien even went so far as to use archaic and downright obsolete English words, so that even the place-names that are in English are often opaque to the untrained eye: witness "Gladden Fields", "Michel Delving", "Wold", "West Emnet" and "East Emnet". How many people know what a gladden is, let alone an emnet?

Merri said,

December 9, 2008 @ 9:41 am

@Helland : the etymology for French rivers Seine and Saône has indeed been suggested to be a Celtic word meaning 'flowing gently', contrary to Rhin and Rhône, linked to a root meaning 'flowing quickly', cf. Greek Rheô.

Calli Arcale said,

December 10, 2008 @ 1:59 pm

For example, Regina ("Queen"), Saskatchewan, was originally called ":Pile o' Bones."

And the place where I grew up, now called St Paul (I suppose you could unpack that to "Saint Small One" or something similar), managed to avoid going down in history as Pig's Eye Landing. I think a certain amount of market pressure is often responsible for such alterations. ;-)

Jens Glad Balchen said,

December 12, 2008 @ 3:57 am

Regarding the name of my hometown, Sound of the Anointed One's Devotion (Kristiansand, Norway), the translation appears to have missed a crucial point. The town was founded by Christian IV of Denmark on the sand banks of the river Otra, hence Christian's Sand -> Christianssand -> Kristiansand. For some reason, the atlas' creators have incorrectly interpreted "sand" as "sound". Perhaps this is due to the similarities between Kristiansand and Kristiansund; the latter's "sund" actually means "sound", which the translators got right.

The correct translation for Kristiansand would be Sand of the Anointed One's Devotion. I still don't know from where they got "Devotion", though.

dennis said,

December 16, 2008 @ 3:18 pm

The story of Nome Alaska that I heard went like this: The city actually had "no name" and that is what the cartographer wrote upon the map……"na" was worn off from the folds in the map itself, thus leaving "No–me" as the name of the city. the rest is history

Carlos Serrano said,

December 26, 2008 @ 10:01 am

In this atlas my country, Colombia, is portrayed as "Doveland," presumably for Latin Columba (dove). But actually Colombia has its name after Christopher Columbus.

jay said,

May 20, 2009 @ 8:45 pm

The United States of North America (the continent) has no name per say… we are a nation of states with no common name for the nation as a whole. Our founding fathers argued and debated over various names and had decided to name our country Columbia but never made it "official".

They did name the nation's capitol city of Washington DC (in the District of Columbia) official but never got around to naming the Nation.

The name Columbia was later claimed by the South American country and the debate was finished.

Columbia was/is the official name for Lady Liberty otherwise known as the Statue of Liberty.

other examples…CBS the Columbia Broadcasting System which depicts a picture of her on their logo.

All in honor of Christopher Columbus of course. The explorer who never set foot in the USA.

Just a little trivia for y'all. enjoy, Jay from MontAlba Tx. (white mountain)

La Victorienne said,

August 2, 2009 @ 8:16 am

Brussels is ‘Marsh Cell’ Hum how did they get to this?

It comes form the germanic broeck (prononce brook) meaning morass, swamp and Sall meaning habitation. So Brussels means habitation on the swamp.

La Victorienne said,

August 2, 2009 @ 8:20 am

I just checked marsh (apparently synonym to swamp) which is fine but cell for habitation, house???

Scott said,

May 31, 2010 @ 10:06 am

Growing up in the 40's I was taught that the "real" name for the Statue of Liberty was "Liberty enlightening the world." I remember it well because that teaching was my introduction to the term 'enlighten.'