Prepositional identity

« previous post | next post »

From Tim Leonard:

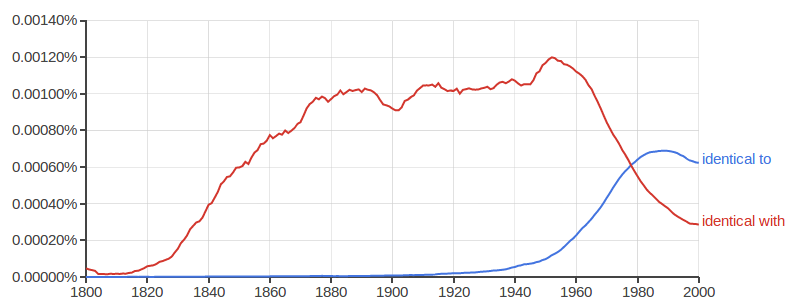

I read here that Arthur C. Clarke wrote in his diary, "… are virtually identical with us." I was surprised that he would use "identical with" rather than "identical to," since I find it ungrammatical. So I checked Google Ngram Viewer, and was delighted to discover that the preposition that goes with "identical" appears to be a previously fixed choice that's in the process of changing:

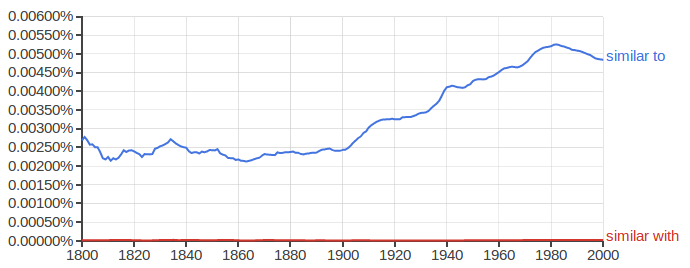

In contrast, similar has always selected for to:

And likewise equivalent:

As Geoff Pullum recent wrote ("At Cologne", 10/2/2013):

The problem is that each specific verb will have certain idiosyncratic demands regarding the particular prepositions it will accept as the head of its preposition-phrase complement. Arrive allows at or in (among others), but not (for example) to or into. And Welcome allows to, but not at or in.

You arrive at or in a place, not to a place, but you welcome someone to a place. That's just the way it is. Nobody promised you a rose garden: nobody guaranteed that languages would be easy or fair or logical or commonsensical. They are simply as they are. Deal with it.

And adjectives are no easier or fairer or more logical.

Also, the rules can change, sometimes quickly.

Jonathan Lundell said,

October 19, 2013 @ 10:53 am

And perversely, the idiomatic choices end up feeling somehow logical. Of course it's "arrive at; "arrive to" just doesn't make sense!

The Ridger said,

October 19, 2013 @ 11:19 am

"Of course it's "arrive at; "arrive to" just doesn't make sense!"

And yet, junior translators will so very often write "arrive to" because the Russian uses "к (to)".

Bill W said,

October 19, 2013 @ 11:35 am

Of course, "identical with", from the beginning of its history, was always wrong–but it was only in the 1940s and 1950s that writers of English who were careful about grammar and usage began to wake up to this truth, not long before they began to recognize that "which" cannot be used to introduce "restrictive" relative clauses.

Ray Girvan said,

October 19, 2013 @ 12:25 pm

"arrive at … arrive to"

And it'll be interesting to see how "arrive into" – currently receiving a lot of peeving re its use on UK onboard train announcements – fares in the long term.

Joshua T said,

October 19, 2013 @ 12:39 pm

I was a little surprised to hear that someone found "identical with" ungrammatical.

After all, I can identify with someone, but not to.

(Yes, yes, one usage doesn't mean the other would occur, and yes, I could identify a local landmark to someone, though that sounds a bit strange to me.)

michael farris said,

October 19, 2013 @ 1:10 pm

I might be misremembering, but I think 'arrive to' is (or used to be) fairly common in some parts of the American South. "It was already dark by the time we arrived to Jackson" doesn't sound weird to me with the right accent.

Of course that doesn't make it appropriate for a sign welcoming visitors in modern Germany.

Bill W said,

October 19, 2013 @ 1:47 pm

@ Michael Farris: some non-standard prepositions introducing verbal complements I've heard in the US South:

We'll go on my car.

Believe on Jesus Christ.

David Morris said,

October 19, 2013 @ 2:10 pm

Acts 16.31

KJV: 'And they said, Believe on the Lord Jesus Christ, and thou shalt be saved, and thy house.'

NIV 'They replied, “Believe in the Lord Jesus, and you will be saved—you and your household.”'

I don't know whether 'believe on' was standard then, or whether this reflects the Greek, or whether it was idiosyncracy on the part of the translators.

DaveK said,

October 19, 2013 @ 3:03 pm

Even odder, "to welcome at" sounds wrong, but the passive voice "to be welcomed at" is not uncommon.

From the Arkansas Gazette online (headlinese but still…)

Arkansas Vets Welcomed at WWII Memorial

Jason said,

October 19, 2013 @ 3:05 pm

@David Morris

According to http://biblehub.com/tr94/acts/16.htm

Acts 16.31

[οι δε ειπον] [πιστευσον] [επι] [τον κυριον ιησουν χριστον].

[And they said] [believe] [upon] [the lord Jesus Christ]

Wiktionary:

ἐπί

upon, on, over, above

"The object of ἐπί may take either genitive, accusative, or dative. There are nuances to each case, and ἐπί is a versatile word which may convey an array of meanings. However, the primary meaning of "upon" is meant in a majority of situations."

I'd bet on a calque or translationism (the KJV is full of them). Bill Ws' interlocutor is undoubtedly directly quoting. The bible belt is a big KJV-only demographic, and its frequent translational infelicities are often used ostentatiously because their jarring sound signals an educated speaker who knows his (KJV) bible and therefore knows "correct" English.

Lazar said,

October 19, 2013 @ 3:09 pm

@DaveK: At the risk of doing what Jonathan Lundell mentioned, I think those aren't the same kind of usage. In the first case it seems to me that "welcome to" is a prepositional verb, whereas in the second case it seems that there's a simple transitive verb "welcome", and "at" merely describes where the welcoming is happening.

J.W. Brewer said,

October 19, 2013 @ 3:21 pm

Interestingly enough, Douay-Rheims has "believe in" in that verse from Acts, consistently with the Vulgate's "crede in Domino Iesu"). The KJV has instances of "believe in" in its NT, but in the first one I spot-checked (John 12:36), the Greek has "eis" rather than "epi." Whether there's a semantic nuance in Greek between believing eis something and believing epi it (and if so whether there's an adequate way to have that distinction flow through in the English) requires more specialized knowledge than I seem to presently possess.

Robert said,

October 19, 2013 @ 3:28 pm

@J. W. Brewer

In Latin, "in" means both "in" and "on". So the KJV and Douay-Rheims are both consistent with it.

J.W. Brewer said,

October 19, 2013 @ 3:38 pm

MWDEU has a lot of entries on words with this sort of which-preposition issue, and the entry on "identical" cites a prescriptivist division of opinion lasting into the 1970's between authorities claiming that only with was correct and those who also accepted to.

Jimbino said,

October 19, 2013 @ 3:41 pm

Eugene Volokh has just cited this post. You should inform him that his use of "forbid [someone] from [doing something]" is ungrammatical. The speaker of English should say, of course, "forbid [someone] to [do something]."

I would tell him myself, but he has forbidden me to post on (prohibited me from posting on and banned me from) his blog, because he can't stand my correcting his bad grammar. I'd grant him some slack that a native Russian speaker merits, if he didn't hold himself out as a grammar maven when it comes to tech writing.

[(myl) But you're wrong — as usual, you're taking your own unexamined reactions to define grammaticality. The NYT index yields 1,210 results for "forbid him|her|me|us|them from", as opposed to 212 results for "forbid him|her|me|us|them to". Why should we accept your judgment over evidence of that kind?]

And where does "advocate for [a cause]" come from? Where I live, smart folks say things like "advocate healthcare for poor people," not "advocate for healthcare for poor people."

[(myl) The usage "advocate for [a cause]" comes from more than four centuries of elite usage: the OED cites e.g.

1660 P. Heylyn Ecclesia Restavrata I. i. ii. 37, I will not take upon me to Advocate for the present distempers and confusions of this wretched Church.

1872 F. Hall Rec. Exempl. False Philol. 75, I am not going to advocate for this sense of actual [i.e. meaning ‘present’].

Please spare us further displays of your ill-informed peevery.]

Yakusa Cobb said,

October 19, 2013 @ 4:26 pm

Ple

Brett said,

October 19, 2013 @ 4:48 pm

I was never aware of "identical with" until grammar checker that came with the ProWrite program on my high school's computers told me that "identical to" was strictly colloquial and inappropriate for more formal prose. (It also thought "demon" was an abbreviation for "demonstration.")

@Jimbino: Actually, it's you who have it wrong. Both "forbidden from eating" and "forbidden to eat" are fine.

J.W. Brewer said,

October 19, 2013 @ 4:56 pm

Just looking at the OED, there are 13th century examples of "belieue" taking both "in" and "on," which seems too early for "believe on" to be merely an overliteral calque from NT Greek, as the Scriptures were not much read in Greek in England at that time.

Jerry Friedman said,

October 19, 2013 @ 5:22 pm

In fact, there's an Old English example of "believe on". I'd bet both forms are calques from the Vulgate, since all the early ones are religious.

I don't think I'd ever say "identical with" any more than I'd say "the same with", but "identical with" doesn't sound as bad (undoubtedly since I've seen it).

I've seen "equivalent with" in student work, so it may be due for a rise in popularity. Or maybe only my students say it.

dw said,

October 19, 2013 @ 6:15 pm

And, of course, there's the whole different from/than/to controversy.

Jimbino said,

October 19, 2013 @ 7:34 pm

Myl strangely thinks quoting centuries-old writers is appropriate in deciding questions of modern English usage. One of his sources apparently capitalizes verbs [Advocate] and common nouns [Church]. No sensible person would pay him attention, much less hire him.

[(myl) You asked where the usage came from, as though it were a recent innovation, and I pointed out that people have been writing about advocating for causes in English for several centuries. But I could have quoted many recent examples, e.g. a random sample from this year's NYT:

Would you pack your bags, organize your family or child care, and get on a plane to advocate for global vaccination?

The enthusiasm and generous spirit that Mr. Sagan used to advocate for science now must inspire all of us.

… use expressive illustrations and powerful text to educate young readers about the effects of prejudice, and to advocate for change.

]

I'm a prescriptivist, of course, with little regard for the n-grams and googling of the descriptivist, who is confident, in facing competition with a descriptivist for a job, of getting it.

[(myl) No, you're a troll, to use the appropriate technical term. Never in your many arrogant and obnoxious comments, here and elsewhere, have you ever offered any substantive information or any interesting examples. Your only role is to insult people and parade your prejudices. So please consider yourself banned here as well.]

And, as a scientist, I appreciate that the value of a particular usage is no less than the n-gram-frequency of occurrance of the usage multiplied by the erudition of the speaker. If not, we'd still be using "nigger."

Mark Twain understood that simple point. Descriptivists don't.

Jonathan Gress-Wright said,

October 19, 2013 @ 8:13 pm

@Jimbino:

Although you correctly recognize that modern usage should not be judged by 16th or 17th century authorities, you fail to allow that usage may continue to change, and that standards of correctness may therefore likewise change.

By nature, people are emotionally invested in their language, and negative reactions to different dialects or language change are found across all societies and cultures. It is natural to feel that one's own way of speaking is the only "correct" one, and that other ways of speaking are aberrations. As one grows in knowledge and maturity, one realizes that other people don't always speak your language and that this is acceptable and normal. Eventually, if you are truly educated and take some linguistics courses, you realize that this holds even for the non-standard varieties of English which you grew up originally to despise.

J.W. Brewer said,

October 19, 2013 @ 8:18 pm

More hilariously, the OED's examples of the transitive variant of "advocate" preferred by Jimbino include a 1789 letter from Benjamin Franklin to Noah Webster in which Franklin complains about this vulgar linguistic innovation (which Franklin thought had somehow crept into AmEng while he had been over in France) and expresses the hope that Webster will "use [his] authority in reprobating" the supposed novelty. (It sounds like Franklin's complaint was not so much the transitive/intransitive issue, but a peeve that verbing the noun "advocate" was itself Just Plain Wrong.)

Carl said,

October 19, 2013 @ 9:06 pm

My 2p: as a quite educated AME speaker I find "identical to" very odd. Perhaps it has something to do with "is". The standard reason claimed for "I am he" rather than "I am him" is that identity is symmetric, and thus "to be" is not a transitive verb. Similarly, "identical with" indicates that both thing are identical with the other, symmetrically, while "identical to" sounds asymmetric. Similarly, it is possible to say "This and that are identical", but not "This and that are superior".

J.W. Brewer said,

October 19, 2013 @ 9:22 pm

Carl: Shouldn't you find "equivalent to" equally odd? For that matter, how about "equal to"? MWDEU saith: "The idiomatic preference for one preposition or another after certain verbs, adjectives, and nouns has been a subject for worry by grammarians since the 18th century."

Graeme said,

October 19, 2013 @ 10:51 pm

What are the respective rates of 'similarity to' and 'similarity with'. My intuition is the latter is far from uncommon. In which case it's interesting that there's no bleeding of usage, at all, into 'similar with'. Doubly so given 'resemblance' can adopt either preposition.

Joyce Melton said,

October 20, 2013 @ 2:26 am

Identical to and identical with seem to have a shade of different meaning to me; I'm sure I use both of them in slightly different circumstances.

For identical with, it feels to me as if you are starting with two quantities and comparing them with each other. For identical to, if seems to me as if you have taken one thing and compared it to some other.

This may just be my own idiosyncratic style. If I had two styles, I could compare them with each other but since I don't, perhaps I can compare my style to someone else's.

Nathan Myers said,

October 20, 2013 @ 2:43 am

To (for?) those of us who had not twigged, Jimbino was having us on.

Well played, sir.

I, of course, was onto you from the first.

[(myl) RIght — it's called trolling, and he's been doing it for years. If he occasionally made a comment out of character, it would be tolerable, but given that all of his (sometimes copious) comments are in the same vein, it doesn't really matter whether he's really a pompous arrogant nitwit or just plays one on the internet.]

Nathan Myers said,

October 20, 2013 @ 2:48 am

I recall a Douglas Adams line, "more differed from than differing". Do Brits' exquisitely tuned ears detect a semantic distinction between "different to" and "different from", suggesting different agency?

Gloc said,

October 20, 2013 @ 4:34 am

This Brit's more or less exquisitely-tuned (but more prescriptivist than descriptivist by habit) ears hear 'different from' as never wrong; 'different to' as an often-unexceptional colloquialism; and 'different than' as always gratingly wrong.

John Walden said,

October 20, 2013 @ 5:52 am

I see it as a kind of visual metaphor:

BrE groups "different" with "separate", "distinct" and so on. The two things being compared are haughtily ignoring each other.

AmE sticks "different" in with "opposed", "contrary" etcetera. The two things are glaring at each other.

Teasing it out further, obviously "similar" and "equivalent" have them nodding to each other, fraternally.

As for "than", it can't be explained away as valid but slightly odd, like most Americanisms appear to the Brits, and I'd imagine vice versa.

I'm with Gloc, it sounds really very wrong.

"Identical with" raises no hackles. I wouldn't say it, but each to their own.

Ellen K. said,

October 20, 2013 @ 8:00 am

AmE sticks "different" in with "opposed", "contrary" etcetera. The two things are glaring at each other.

John Walden, I'm puzzled by that. That would imply that we Americans say "different to". Yet we don't. At least, to me, "different to" sounds completely wrong. And a quick Google search brings up this page with state showing "different to" to be quite rare in the U.S., and much more common in the U.K. http://alt-usage-english.org/excerpts/fxdiffer.html

John Walden said,

October 20, 2013 @ 10:11 am

You're quite right.I got myself all twisted around.

mollymooly said,

October 20, 2013 @ 11:09 am

@Nathan Myers: I think the sense of "I'm more differed from than differing" is "I do not depart from the norm; I am the norm from which others depart". (The allusion is of course to "more sinned against than sinning" in King Lear.)

@Joyce Melton: I can conceive a plausible distinction between "identical to" and "identical with", different from your distinction. A perfect copy is identical to the original but not identical with the original. OTOH Hesperus is identical with Phosphorus. I am annoyed that this distinction fails to align with the putative distinction between "compare to" and "compare with".

Rodger C said,

October 20, 2013 @ 11:59 am

The question of Greek NT usage is complicated by the fact that the NT was mostly written by L2 speakers and some of the Greek is just bad. What's the status of pisteuein eis in L1 Classical writers, or, for that matter, Luke/Acts?

Bill W said,

October 20, 2013 @ 1:40 pm

"What's the status of pisteuein eis in L1 Classical writers, or, for that matter, Luke/Acts?"

πιστεύειν normally takes a dative complement in Classical Greek. Usages with prepositions seem to be later and perhaps exclusively Judaeo-Christian ("Judaeo" because one of the cites in Liddell-Scott-Jones is from the Septuagint):

http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0057%3Aentry%3Dpisteu%2Fw

But I suspect that the idea of "belief in" a god is foreign to non-Judaeo-Christian Greek: unlike Judaism or Christianity, pagan gods demand emphatically that you affirmatively believed "in" them as part of your religious obligations, just that you sacrificed to them and observed proper rituals.

The basic meaning of πιστεύειν is to trust someone or to believe someone in the sense of believing that what they say is true, not to accept a god as a real being.

Faldone said,

October 20, 2013 @ 4:45 pm

Jimbino seems to be an advocate of the prescriptivist credo: If it works in practice but not in theory something must be wrong with the practice.

Brett said,

October 20, 2013 @ 7:36 pm

Unless I am mistaken, Jimbino has previously stated that he is not even a native English speaker, making his trolling in connection with these topics even trollier.

Mar Rojo said,

October 21, 2013 @ 2:01 am

How so, Brett?

Rodger C said,

October 21, 2013 @ 8:01 am

John Simon lives!

Andrew Bay said,

October 21, 2013 @ 8:13 am

If I "arrive into" something, that is generally bad. In my mind, either I personally or my car has crashed into something. So, I mentally fix arrive into to be euphemistic for "crashed into".

Otherwise, "to" has too much motion to be the place that you come to rest when you arrive somewhere. "At" and "in" do not imply so much motion so they compliment the moving-to-rest transition that arrive involves.

"I am going to the car" works while "I am going at the car" does not mean the same. (Interestingly, it sounds like you are picking a fight with the car or charging (running at) it.) "I am going in the car" indicates that you are planning to use the car to go somewhere else. "I am going into the car" sounds like you are about to be involved in a collision.

(Compare going to the sauna and going into the sauna. The former means you visited the location, but not necessarily that you used it. The latter indicates that you used the sauna.)

Brian said,

October 21, 2013 @ 8:58 am

Which is better: "in regard to" or "with regard to"? Almost every style and usage guide I've read talks about how one ought not to use "in regards to" or "with regards to." But none, it seems, talks about whether "in" is preferable to "with," or vice versa, or whether it even matters. "In regard to" strikes me as more old-school, and I would suspect, though I have no authority to support my suspicion, is more common. Yet lawyers and judges seem to use "with regard to" with much more frequency than "in regard to."

[(myl) Dunno about "better", but usage has apparently been changing, in the direction indicated by your suspicion:

]

Jongseong Park said,

October 21, 2013 @ 12:06 pm

I seem to remember that passengers arriving in Paris Charles de Gaulle Airport were greeted with a banner saying "Welcome in Paris" or something similar.

Surprises in data | Stats Chat said,

October 21, 2013 @ 11:57 pm

[…] Language Log, this is an example of linguistic change in […]

BobW said,

October 22, 2013 @ 1:58 pm

There is a denture commercial currently on TV that is grating to my sense. If I recall correctly it goes: "…different to regular teeth." – Ah! Found it: http://www.excellentediting.net/as-heard-on-tv/ "A Polident ad on TV says, 'Dentures are different TO real teeth.'”

Seiichi MYOGA said,

October 30, 2013 @ 6:13 pm

You might be interested to find that the same thing happens with the pair of "compared with" and "compared to."

(Sorry, I'm not sure how to display the Google Ngram Viewer chart here.)

The results of Google Ngram Viewer suggest that this is not a mere coincidence but that around the 1980s, something happened that affected the preferred choice between "to" and "with."

You say "according to" but not "according with." However, as a VP, you use "accord with" but not "accord to." Only "with" is compatible , for example, with "comply" and "be consistent." For "to," the opposite applies to "consent" and "be related." You can use both "with" and "to" after "agree," but the meanings are different. In contrast, you detect no meaningful differences between "talk to" and "talk with."

As far as the choice between "identical to" and "identical with," what comes to mind foremost (for no reason) is something like this:

They danced to the music.

[(myl) You can just use the URL, but here's the picture:

Also too:

In these cases, at least, "to" has been on the rise since 1920 or so.]

Seiichi MYOGA said,

October 30, 2013 @ 9:23 pm

Thank you for providing the chart, moderator.

And your example makes it clearer what is at issue here. When you compare two things, you connect one thing "with" another. You can also relate one thing "to" another. "To" and "with" have competed with each other, and now the former seems to be invading into the territory of the latter. Now the question to ask is,

What is happening that make native speakers of English choose "to" over "with."

I hope you start a new thread [related to/connected with] the core meanings of "with" in question, if you like.

Seiichi MYOGA

As for similarity, it seems to be connected with (or related to) degree.

(i) Our house is [as big as / no bigger than] yours. (suggesting that there is a similarity in size between our house and your house)

You could also include the figurative use.

(ii) John is as busy as a bee. (simile)

(iii) Our garden is no bigger than a stamp. (hyperbole)

And I think you would accept (iii) as an example of analogy.

(iii) A whale is no more a fish than a bat is a bird. (WHALE:FISH::BAT:BIRD)

Considering this, we could tentatively conclude that "to" in "similar to" might come from the "(up) to" reading rather than the "goal" reading.

Eneri Rose said,

November 3, 2013 @ 6:59 pm

Do other languages change preposition usage as quickly and extensively as does English? Is this a characteristic of a highly analytic language?

bevrowe said,

November 4, 2013 @ 2:02 pm

Our local surgery has a screen where you can book in that you are present for your appointment rather than queuing up to report at reception. The screen displays in large letters: "TOUCH HERE TO ARRIVE FOR YOUR APPOINTMENT"