First grade science card: Pinyin degraded, part 2

« previous post | next post »

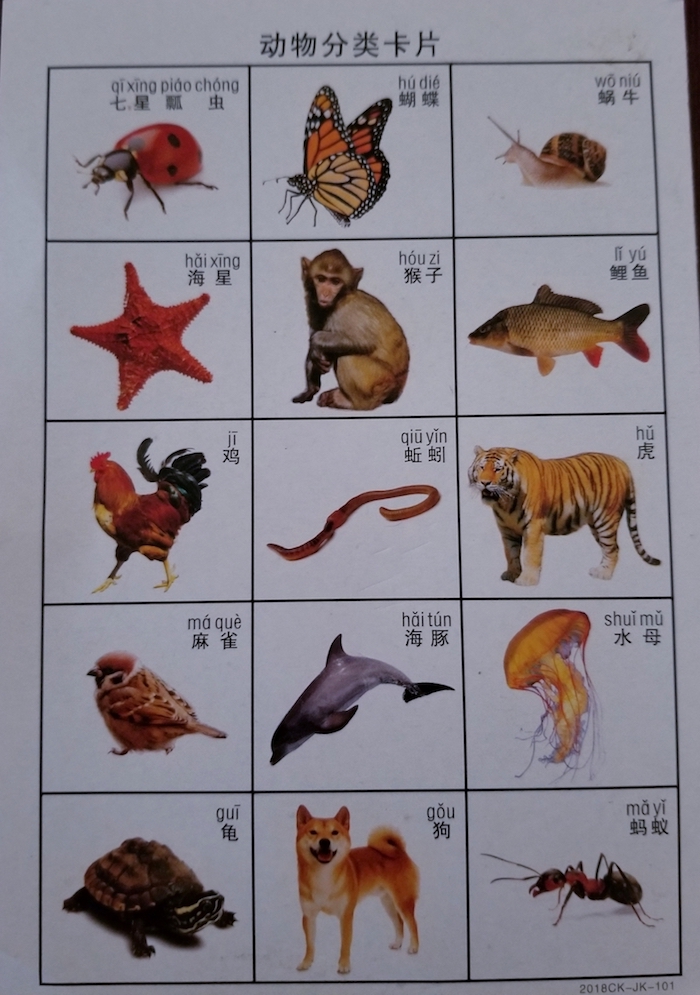

Another science card given out to first grade students in Shenzhen, China (see "Readings" below for the first one):

The title reads:

Dòngwù fēnlèi kǎpiàn

动物分类卡片

("Animal classification card")

Although this card superficially is not as forbidding as the first card in this series, it actually poses an equal number of pedagogical and linguistic problems.

In the first place, although the labels given for each picture are for single items, the syllables are not linked together to show that they are words. This is especially misleading in cases like húdié 蝴蝶 ("butterfly"), where neither of the syllables means anything by itself ("húdié" is a disyllabic morpheme — of which there are quite a few in Sinitic from ancient times).

Some of the words, although they designate simple things, are challenging for first graders. Take the word for "ladybug", which nearly any first grader, or even kindergartner can master easily in English. I remember this from before I went to first grade:

"Ladybug, ladybug, fly away home;

Your house is on fire and your children are gone."

I used to love to recite this to these little creatures as I launched them from my hand.

In Mandarin, this little beetle is called "qīxīngpiáochóng 七星瓢虫", which is quite a mouthful for a little tyke, not to mention that the third character is a bit of a nightmare for a child to write (it means "ladle; dipper", so the whole name may be translated as "seven star ladle bug", even though taxonomically they are not considered true bugs, hence they are also called "lady bird" and "lady beetle" in English).

The next creature, the wōniú / guāniú 蜗牛 (lit., "cochlea cow"), has special meaning for me, since I kept a pet snail named Arnold for more than five years (see here, here, and here).

In all three of these instances and for most of the other animals on this card, it would make better pedagogical and linguistic sense to join the syllables of these terms to show that they are words, not separate syllables.

Of the remaining three items on the card, hǔ 虎 and guī 龟 are not referred to that way in the vernacular, but as lǎohǔ 老虎 ("tiger") and wūguī 乌龟 ("tortoise; cuckold"). As for jī 鸡, it would probably be less confusing to refer to the animal pictured as a gōngjī 公鸡 ("rooster") than just as a generic chicken.

Overall, this card evinces a lack of distinction between literary and vernacular registers, an earmark of overemphasis on the mostly monosyllabic script at the expense of the mostly polysyllabic language.

Readings

- "First grade science card: Pinyin degraded" (4/11/19) — with extensive references to character amnesia, digraphia and diglossia, word division, the uses of Pinyin, etc., also applicable here

- "'Butterfly' words as a source of etymological confusion" (1/28/16)

- "Polysyllabic characters in Chinese writing" (8/2/11)

- "Language vs. script" (11/21/16)

- "Mixed literary and vernacular grammar" (9/3/16)

- "Annals of literary vs. vernacular, part 2" (9/4/16)

- "Latin Caesar –> Tibetan Gesar –> Xi Jinpingian Sager" (3/20/18)

- "Pinyin for the Prez" (10/25/18)

- "Peking University president misreads an unobscure character: monumental implications" (5/5/18)

- "Xi Jinping's reading errors multiply" (12/28/18)

- "More literary troubles for Xi Jinping" (1/3/19)

- "Word, syllable, morpheme, phoneme" (10/6/18)

- "Too hard to translate soup" (9/2/18)

- "Of knots, pimples, and Sinitic reconstructions" (11/12/18)

- "GA" (8/6/17)

- "Of reindeer and Old Sinitic reconstructions" (12/23/18)

[h.t. Alex Wang]

Thaomas said,

April 14, 2019 @ 3:28 pm

Curiously, I can "read more of this post" only by looking at the comments. ????

_hzw said,

April 14, 2019 @ 4:00 pm

I cannot speak for other Chinese, or any first grader nowadays, but I loved the word "七星瓢虫" when I was even in kindergarten, which was 25 years ago, in southern part of China.

I still remembered the time we went out into the wild and looked for these little bugs, caught them and showed them to our teacher, repeating the word in Mandarin. I don't remember any problem speaking out the word or remembering the writing, although, surely, I was not able to write the character "瓢" until much later. Oh, and my mother tongue is Hoisanese.

David Morris said,

April 14, 2019 @ 4:29 pm

In my childhood in Australia we called them ladybirds. I don't know what children or anyone else call them now. AFIAK ladybird is more used in UK/Aus/NZ/?Can and ladybug in US.

Alex said,

April 14, 2019 @ 5:01 pm

@David Morris,

I never knew they were called ladybirds in the UK until I started buying books here for my children. There is that great publisher of children's books Ladybird.

번하드 said,

April 14, 2019 @ 5:02 pm

ladybugbirds? In German, "Marienkäfer". In Korean, "무당벌레" (shaman bug, probably because it's so colorful). In Swiss German, "Himmälgüügäli".

Alex said,

April 14, 2019 @ 5:21 pm

When looking at the card when my son brought it home, I noticed many of the things Professor Mair mentioned.

The one thing that made me think was li yu, I wondered what kind of fish that was. Then it made me realize why I have found that not many kids here know the equivalent breeds of different animals or classification of trees as compared to their economic equivalent in the US.

Taking fish as an example, growing up in the suburbs one could easily name and write 5 to 10 types of fish or 5 plus breeds of dogs.

After looking up the hanzi a number of fish I knew since 4rth grade I now realize why kids here lack the ability to write stories with details.

Alex said,

April 14, 2019 @ 5:40 pm

As a follow up

one only needs to look up

salmon

bass

cod

trout

flounder

perch

mackerel

pufferfish

to realize how unscalable the language is to the average person to be able to write detailed stories.

one can try shades of color too. Many shades in English are from other plants and minerals

Ruby red slippers

emerald green

violet

sapphire blue

as a quiz zi jia zhi zui tai yang niao

ruby cheeked sunbird Chalcoparia singalensis

its a bird species here in China.

Phil H said,

April 14, 2019 @ 6:55 pm

It's the "fenlei" that gets me. These animals are not divided into categories in any way!

Incidentally, when the kids are getting low-quality linguistic materials like this for their own language, just imagine how bad their foreign language materials are. Ours don't have to look at the English materials they get from school, because they speak English at home, but I occasionally take a glance, and it makes me shudder. Any kid who actually tried to learn English from the school materials would be doomed.

Lars said,

April 14, 2019 @ 7:18 pm

@Pjil, "It's the "fenlei" that gets me. These animals are not divided into categories in any way!"

Google Translate tells me that the translation of "taxonomy" is 分类 (Fēnlèi) as well. Sure, they could've used a simpler term, but I'm not sure this is as bad as you think?

Alex said,

April 14, 2019 @ 7:18 pm

@phil

Totally agree on the public school English materials. Its shocking how rather than teach the kids step by step via phonics and simple phonics based stories. They start right in with random phrases.

You would not believe the number of kids who can read cat and hat but not rat or fat. They are taught to memorize words.

liuyao said,

April 14, 2019 @ 10:30 pm

Normally for complete sentences in pinyin I would agree with Prof Mair, that to write with proper word spacings makes it a lot easier to read. But here, in the backdrop that pinyin in full sentences is not a thing in China, it makes sense here as phonetic annotation if the kids are not expected to see pinyin words when they grow up.

I think children very easily get hold of the concept of a syllable, and the fact that each syllable corresponds to a Chinese character (long before they could read any). So, to write it as one word would present an extra complication that they'd have to mentally separate the syllables. Just look at qixingpiaochong, or perhaps better rendered as qixing piaochong, for it is a particular species of ladybug. (And I agree with _hzw that it was a lovely word when I grew up.) While we are at it, those Latin names of dinosaurs that American kids had to put up with are beyond ridiculous. Well, kids who can't read yet seem to have no more trouble than other strange words, so it probably is mostly the parents (who can't read Latin, and in a number of cases, pinyin) that have to struggle.

Alex said,

April 14, 2019 @ 10:59 pm

@liuyao

On the dinosaurs, I was curious was it to spell or say or read that is/was difficult in your mind?

I'm trying to figure out what kids might find difficult.

Thanks

Victor Mair said,

April 14, 2019 @ 11:24 pm

@liuyao

My point was that thirty and more years ago language textbooks in China did have word separation and adherence to well thought out orthographical rules. It is only through retrograde language policies that current authorities have dispensed with them, thus depriving students of important information about their language. That's what caused distinguished language reformers such as Wang Jun to be "so angry they could die" (qì sǐle 气死了).

liuyao said,

April 15, 2019 @ 12:53 am

@VHM

I do understand your point, which was also laid out in the previous post on this. I don't know how it would have turned out had there not been a retrograde.

@Alex

Everything: to spell, to say, to read, and to have some inkling of what the name is supposed to mean to help remember it (though that's just my perception; kids don't bother with knowing what they mean). T. rex must be the simplest of all (and kids probably think it was one word), but almost every other dinosaur is more difficult than qixing piaochong, I would say.

I'm reminded of the ongoing effort by one young botanist (Liu Su 刘夙) to translate the official Latin names of all plants into Chinese (notably not always literal translations), and maybe they should do the same for English and other languages. I would recommend his works (including translations) for a good example of what popular science in Chinese is like.

Alex said,

April 15, 2019 @ 1:09 am

@liuyao

Thank you for your response. Was that for non native speakers?

I have found at least for native speakers and little kids here in China the saying of dinosaur names to be quite easy. Its not just dinosaur names its almost anything.

For dinosaurs there's this super cartoon called Dinosaur train. Most kids here in my garden in Shenzhen learn the names rapidly as I did pre internet and tv shows. Most easily learn 10 or more. As for reading the names thats a little harder but once they have a good grasp of phonics they kinda learn to recognize just a component or two and then repeat the oral from memory. Spelling certainly is harder for young kids.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Dinosaur_Train_episodes

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dinosaur_Train

The average child in my garden can watch this and learn the names but not understand all the conversation.

I think young kids can learn much faster than adults. For example its very hard for me to remember Chinese names even though Chinese was my first language and used almost at home almost exclusively even though born in the US.

Victor Mair said,

April 15, 2019 @ 6:37 am

@liuyao

Intelligent people of good will can always turn retrograde around to positive, progressive, and rational again if they want to. Human beings are not doomed to live under benighted policies.

Philip Taylor said,

April 15, 2019 @ 9:30 am

Alex ("Totally agree on the public school English materials. Its shocking how rather than teach the kids step by step via phonics and simple phonics based stories. They start right in with random phrases.

You would not believe the number of kids who can read cat and hat but not rat or fat. They are taught to memorize words").

I changed school regularly as a child (because my parents kept moving house) and once experienced the shock and horror of being expected to use phonics at my new school having previously learned "look and say". It was the most depressing and humiliating thing I had ever experienced. I knew that the letters were called "A", "B, "C", etc., yet now I was supposed to forget that and pretend that they were /a/, /b/, /s or k/, etc. Phonics may be useful for slow learners, but please, allow and encourage the normally able to use look-and-say from the outset.

Jerry Friedman said,

April 15, 2019 @ 9:53 am

I'm a bit surprised that the card shows a picture of a North American butterfly. Surely a good picture of some common Chinese species was available.

cliff arroyo said,

April 15, 2019 @ 11:00 am

" once experienced the shock and horror of being expected to use phonics at my new school having previously learned "look and say""

People are different. I would have probably never learned to read with 'look and say' while I took to phonics very easily… though where I was the names of the letters were taught distinctly from the usual sounds. So the name of C was /si/ while were taught that it 'didn't have it's own sound and was pronounced like k or s.

Jichang Lulu said,

April 15, 2019 @ 11:18 am

The cards in these two posts are beautiful, but it's regrettable to see a neglect for proper Pinyin spelling. The text on the jiyu card in the previous post would have been much more readable if properly syllabified, and even the hanzi names on this one would look better without the intrusive spacing. Whatever one may think about the relative merits of other Romanisations, the design and implementation of Pinyin is something Chinese specialists and educators should be proud of; a standard, viable transcription system is of great help in multiple areas, including administration, journalism, science and of course education, especially first-language education and the promotion of literacy.

Sinologists, as well as others familiar with other non-Latin scripts, can appreciate the usefulness of having just one fully functional Romanisation system available for all audiences and all kinds of writing. (See Language Log posts with Tibetan or Mongolian.) Efforts to promote Chinese as a second language, identified as a priority by the relevant authorities, would also be greatly hindered by a neglect of Pinyin orthography.

Learning animal and plant names in Chinese requires memorising many new characters, some of which are relatively rare. Lúyú 鲈鱼 will be familiar to readers of Li Bo; for the huíyú (popular in Shanghai), however, one needs the character 鮰, whose simplified form is missing from many fonts (cf. this interesting article) and often ends up replaced with 回, which doesn't seem to hinder trade one bit. Excessive emphasis on hanzi risks turning an introductory-level ichthyology class into a class about the writing system. The writing system is itself an important subject, but in this context it's just a distraction; imagine children this age being required to memorise binomial names. Learning and understanding the relevant vocabulary as it is spoken (while being presented with the hanzi spelling) seems the priority here, and that would be better reflected by a Pinyin-centred design. In particular, making Pinyin more readable by following proper spacing rules seems especially important in this kind of material.

Alex said,

April 15, 2019 @ 9:26 pm

@philip taylor

@ Cliff arroyo

thanks for the feedback and advice. It definitely is true by your responses people are different.

I think on an individual level perhaps look and say might be ok if that child has a strong self decoding ability.

On a mass level for example small class to large its best to teach phonics.

My own kids found Kumons preschool to be super. From my experience as a non professional working to help community kids, I have found if they understand the building blocks and understand there are exceptions it allows them to decode when they see words they havent seen before or have forgotten.

The first kumons goes through short vowels. at ap ad etc ed em eg etc

many knew what an umbrella was sound wise and those with reasonable phonics were able to decode um brell a upon seeing it for the first time. as they ran through hum gum yum and sell tell bell fell.

As mentioned structured learning of phonics might not be needed for those who can decode subconsciously from look and say but I still think it doesn't hurt to know the basics.

Alex said,

April 15, 2019 @ 9:34 pm

@Jichang Lulu

Thanks for the feedback. I had to google your fish

"Chef Wei says that for fish with a firm texture and somewhat earthy taste such as huiyu (also called Yangtze herring, a kind of longirostris"

It seems most fish end with yu though there are exceptions.

Learning a broad array of taxonomy and for minerals and detailed parts of daily items seems incredibly difficult especially if one needed to write essays in 3rd grade.

It would seem one would have to look up how to write so many characters if details were required.

WSM said,

April 16, 2019 @ 7:40 am

Curious: Why is 气死了 segmented into "qi4 si3le"? I would have instinctively grouped the verb with the resultative complement "qi4si3" and separated out the le. Is 看到 romanized as "kan daole"? Is there a standard / rule for how to segment such things?

Victor Mair said,

April 16, 2019 @ 9:06 pm

From Mark Swofford:

According to Yin Binyong, the answer is basically "It depends," though for him the choices would have been between "qisi le" and "qisile" (not "qi sile"), and between "kandao le" and "kandaole" (not "kan daole").

Regardless, le is a relatively complicated point to handle in Pinyin orthography.

The basics of Mandarin’s three tense-marking particles — zhe (著/着), guo ( 過/过), and le (了) — are here:

http://pinyin.info/news/2009/how-to-write-verbs-in-hanyu-pinyin/

http://www.pinyin.info/readings/yin_binyong/o05_verbs.pdf

Le is by far the trickiest of the three:

http://pinyin.info/news/2009/le-redux/

http://www.pinyin.info/readings/yin_binyong/o09_le.pdf

As I note in one of my posts on this topic, "I suspect that’s the sort of thing that may well change (for the simpler) once Pinyin makes it out into the world of popular usage as a script in its own right. But for now I’m just givin’ the rules as I find 'em."