Sinographs for "tea"

« previous post | next post »

It is common for Chinese to claim that their ancestors have been drinking tea for five thousand years, as with so many other aspects of their culture. I always had my doubts about that supposed hoary antiquity, and after many years of research, Erling Hoh and I wrote a book on the subject titled The True History of Tea (Thames & Hudson, 2009) in which we showed that tea-drinking did not become common in the East Asian Heartland until after the mid-8th century AD, when Lu Yu (733-804) wrote his groundbreaking Classic of Tea (ca. 760-762) describing and legitimizing the infusion.

Since people in the Chinese heartland were not regularly drinking Camellia sinensis qua tea before the mid-8th century, I long suspected that they did not have a Sinograph for tea (MSM chá) either. Rather, based on my reading of texts and inscriptions dating from the 7th c. AD and earlier, I hypothesized that the character now used for "tea", namely chá 茶, was a sort of rebranding (by removing one tiny horizontal stroke) of another character, tú 荼 ("bitter vegetable").

Adam Smith, a specialist on early inscriptional materials, has assembled the following observations to flesh out our findings with more specific details. [N.B. Beyond this point is for those who are advanced in the study of the Sinographic writing system.]

Was just thinking about your interesting question. There are a lot of confused opinions about this, and it is quite complicated. I think your sense that 茶 appears only after ca. 8th c. is correct. In fact, * seems to be the most common writing before that. There must always have been weird, or incorrect, or non-standard ways of writing cha "tea", just like with any other character, but what you are asking about, I suppose, is when do we start seeing 茶 contrasting with 荼, with the former as the normal way of writing cha "tea".

[*VHM: U+2363B 木荼 (joined together left and right as one character); pronounced tú or chá in MSM. This character also appears several times below and is marked with an asterisk.]

The following are the most relevant things that come to mind.

1. 茶 is not so much a substitution for 荼, as just another way of writing it. In medieval mss. the bit at the bottom of 茶 is sometimes written as in 茶, sometimes as in 荼, sometimes like 未, and sometimes like 示. I guess a really fussy transcription might try to distinguish some of these, but I think it is better just to think of them all as 荼.

See the forms in this Qieyun ms. fragment from Dunhuang.

2. 荼 makes historical sense as a character, since yu 余 would be a perfectly regular speller for the Old Chinese source of the Middle Chinese pron. of cha "tea". The bottom half of 茶 has no meaningful analysis: the 艸 makes sense, but the bottom bit is just an arbitrary collection of strokes.

Although 余 is a regular OC spelling for cha "tea", it *looks* (or *sounds*) a bit irregular by the MC period (and in Mandarin, too – we tend to think of 余 as spelling “yu”, “chu”, “xu” or “tu”, not "cha", right?). That is because cha "tea" is a division ii (二等) word, which meant that it developed an MC initial (retroflex stop) and rhyme (ma yun 麻韻) that were rare amongst words spelled with 余. So 余 became opaque as a spelling for cha, and was reproduced purely visually, and therefore inexactly.

3. We can track the appearance and spread of the distinction 荼-vs.-茶 by comparing Qieyun rhyme-book manuscripts with each other and the Guangyun. There seem to be four Qieyun mss. in which the relevant page survives. They all assert that * is the regular writing for cha "tea" (while listing 荼 as a homophone, but only in sense "bitter vegetable 苦菜").

S. 2071 (切三) *:春蔵草葉,可為飲,西南人曰葭荼。

“cha: leaves of a plant stored in spring, which can be made into a drink. The people of the Southwest call it jia-tu (jia-cha?).”

(Easy to read on the ms.)

P.2011(王一) *:…草葉,可為飲,巴南人曰葭

。

(I can't actually see most of this on the ms.)

王三 *:春蔵草,可為飲用。

(This is the complete 706 CE ms. in the Gugong collection.)

王二 *:一本作梌。春蔵草葉。亦茶。

(I haven't seen the image.)

Only the last mentions 茶 as an alternate writing (and actually one would need to check the ms. image, since the transcription might be an error for 荼).

So, I would say that ca. 700 CE, 茶 has not yet attained any kind of established status contrasting with 荼, not even that of an acknowledged 俗字.

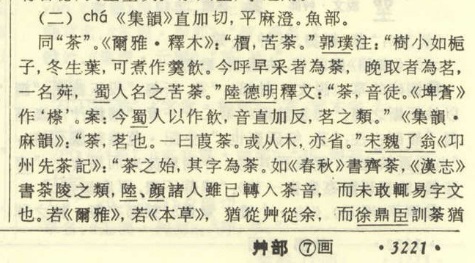

With the Guangyun (1007 CE), the modern graph茶 gets an entry of its own, but it is still the 俗體 to the 正體 of *:

* 春藏草葉,可以爲飲,巴南人曰葭

。

茶 俗。

http://ytenx.org/static/img/

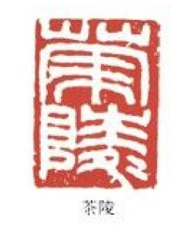

4. The seal you are referring to is probably the seal which reads "Chaling 荼陵" from a Han tomb, 魏家堆 M19, near Changsha. I can't find the report, if there even is one, but the seal is illustrated in this book.

(No page number on Google Books, but I've attached the seal impression.)

One could argue about whether the bit at the bottom of 荼 on the seal is written as in 荼, or more like 未, or something else. But in the end, it is best just to think of the character as荼, and there is no need for stroke-by-stroke hair-splitting. Regardless, it is certainly not 茶-distinct-from-荼.

This Chaling 荼陵 appears in the Han shu "Di li zhi". Yan Shigu gives two alternative fanqie spellings: ye 弋奢切 and cha 丈加切. These sound pretty different in Mandarin, but they probably come from the same OC source (something like *lˤra) via two dialects. The same place name also appears in the “Wang zi hou biao” of the Han shu, and then Yan Shigu says it is pronounced tu 塗. That would be OC * lˤa. It is sometimes said that this Chaling is named for the tea which was grown there. I’ve no idea whether that is true.

5. The Hanyu da zidian has a couple of interesting discussions by Wei Liaoweng (early 13th c.) and by Gu Yanwu (17th c.). It is clear that by Wei’s time, 茶-distinct-from-荼 was the normal way of writing cha “tea”. Wei notes that this was already true in the time of Xu Xuan (a.k.a. 徐鼎臣, 10th c. editor of the Shuowen).

It is interesting to see that both Wei and Gu are making a version of the argument that I made in 2., above, but without the modern understanding of regular sound change, and without a clear distinction between the written and spoken word. In essence they are saying that cha “tea” used to be pronounced homophonous with tu 塗 “road”, and that when the pronunciation tu “turned into” (zhuan ru 轉入) cha the change stimulated the new writing 茶 (somehow). Gu Yanwu says that “in old times, the ma rhyme (麻韻) had not yet separated.”

What we would now say is that the source of the Middle Chinese division II rhymes like ma 麻 was a medial *r, largely ignored by Old Chinese spelling. So 余 could spell both cha < *lˤra “tea” and tu < *lˤa “road”. By Middle Chinese, regular sound changes conditioned by that medial *r meant that this pair no longer looked such a good candidate for a common spelling: cha < drae “tea” vs. tu < du “road”. So the writing for “tea” was free to wander off away from 余.

I was especially pleased with Adam's finding that the seal from a Han (206 BC-220 AD) tomb that supposedly reads Chálíng 茶陵 ("Tea Ridge") — and is often cited as evidence for the existence of the character chá 茶 before the Tang period (618-907 AD) — looks for all the world as reading Túlíng 荼陵 ("Bitter Vegetable Ridge").

Adam's phonological analysis of chá 茶 vs. tú 荼 is also most reassuring, and comports well with what I've been saying for decades about "chá" as being a late pronunciation in comparison with tú.

I am particularly grateful to Adam for his detailed documentation and analysis of the character *, which is key for the understanding of the transition from tú 荼 ("bitter vegetable") to chá 茶 ("tea"). What it indicates is that this plant was arboreal (as Camellia sinensis in its wild, non-domesticated state grows, not as a low bush) and that it was clearly mù 木 + tú 荼, not mù 木 + chá 茶.

Taking all of the above into consideration, this Language Log post constitutes the most concentrated, convenient, comprehensive, and integral presentation of the epigraphical, inscriptional, paleographical, and phonological evidence concerning the development of the Chinese character for tea, viz., chá 茶.

Readings

"Caucasian words for tea " (1/26/17)

"Multilingual tea packaging " (4/7/18)

"Trump tea " (1/13/17)

"Kung-fu (Gongfu) Tea " (7/20/11)

"Two brews " (2/6/10)

"Mandarin Pu'er / Cantonese Bolei 普洱" (8/5/11)

Victor H. Mair and Erling Hoh, The True History of Tea (London: Thames and Hudson, 2009), especially Appendix C on the linguistics of "tea").

Chris Button said,

January 10, 2019 @ 10:50 pm

A great read.

I would challenge the reconstruction of a medial -r- in 茶 which I believe should be reconstructed in Old Chinese in exactly the same way as 荼 as *láɣ. It seems that the /a/ vowel sometimes lengthened before the fricative coda such that 荼 remained as *láɣ while 茶 shifted from *láɣ to *láːɣ to give slightly divergent pronunciations of the same word (compare the different phonological developments of 車 *kɬàɣ > *kɬàːɣ "chariot" and 杵 *kɬàɣʔ "pestle" in that regard). Following the phonological discussion in Pulleyblank's 1995 "OC Glottals" paper (not specifically related to 茶), I think the long *-áː- in 茶 would have developed a reflex like that of *-rá-. However, I should add that I do not follow Pulleyblank's concomitant proposal for phonemic vowel length, and prefer to treat it as a case of sporadic vowel lengthening similar to that found in the "trap-bath" split in English.

JB said,

January 11, 2019 @ 3:50 am

Interesting. I'd only ever seen this 荼 in connection with 荼毗, Buddhist cremation.

David Marjanović said,

January 11, 2019 @ 6:58 am

*applause*

Victor Mair said,

January 11, 2019 @ 8:34 am

From Connie Cook:

Interesting question. The graph 荼 (old form of 茶) appears in vol. 8 of the 上海博物馆藏战国楚简 (p. 126) as a verb which the editors read as overcoming bitterness. 我們人既荼。 I found this single pre-Han example in the online database "漢語多功能字庫 Multi-function Chinese Character Database." It does not discuss a verb form. It does say it is an early word for bitter herb (and matches up with info one can find in the Shuowen jiezi and the Peiwen yunfu). It does give the Han seal form that you mention.

One avenue of interest might be the eastern Han medical recipe texts that are appearing in increasing numbers. Of interest will be those found recently in Sichuan (Mianyang, I think) and in the Haihunhou tombs. Neither is published yet. Maybe reach out to Miranda Brown who translated the Wuwei example and no doubt has her eye on those. She has also worked some on stele which is the only other early CE inscriptions of note (Gil Raz on these too maybe, esp. those with Daoist affiliations).

Chris Button said,

January 11, 2019 @ 1:00 pm

Regarding the /ɣ/ (~/ɰ/) coda of 荼 *láɣ and 茶 *láːɣ < *láɣ (which seems to have been a phonological requirement for a properly formed syllable for what on the surface may essentially be considered an "open" syllable), a possible association can be drawn with the velar coda in Written Burmese "lak(phak)" (now pronounced /ləpʰɛʔ/) tea(leaf). A good typological comparison may be found with the association of 來 *rə́ɣ and 麥 *mrə̀k wheat with PIE *mr̥k- barley.

Richard Sears said,

January 11, 2019 @ 9:31 pm

余 is the original character for tea 茶.

It consists of an inverted mouth character 亼.

That is an upside down 口.

You can find the same situation in the characters 會今禽食合令侖命僉 and 龠 all of which mean and inverted mouth, either talking or eating or drinking as in 㱃酓.

The bottom part of 余 is in the seal character .

It can indicate flax or hemp, but it can also indicate a plant whose leaves are easily striped, which is “tea”

The oracle character is derived from the bottom part 屮 which means grass also indicating the drinking of “tea”.

The oracle character dates to 1,500 BC

http://hanziyuan.net/#%E4%BD%99

Richard Sears (Uncle Hanzi) said,

January 11, 2019 @ 9:34 pm

The bottom part of 余 in the seal character is it can indicate hemp or flax, but in this case indicates "tea" leaves which are stripped off the plant.

David Marjanović said,

January 12, 2019 @ 6:27 am

Sometimes?

That would be a really strange thing to happen.

There I can easily see the consonant cluster *ɣʔ inhibiting the lengthening of the preceding vowel; but you're not reconstructing a cluster for 荼.

Buuut… the TRAP/BATH split isn't sporadic. It's almost perfectly conditioned: BATH occurs before fricatives (bath, grass, glass), and before /n/ followed by certain other consonants (can't, plant, Francis, trans-). The one exception I can think of right now is ant, which retains TRAP in order to differ from aunt; I strongly suspect that's a borrowing from an accent that lacked the split.

Chris Button said,

January 12, 2019 @ 9:39 am

@ David Marjanović

Respectfully, I think you're asking the wrong questions. What you should be asking is how on earth could the long vowel in 茶 *láːɣ (< *láɣ) trigger retroflexion of the onset? For that, I would refer you to Pulleyblank's 1995 article which involves the concept of analogy that should also provide answers to your other questions. Alternatively, you could just go ahead and follow the -r- infixation after a lateral proposal along with a randomly specified morphological function allowing a shift from tea (plant) to tea (drink)!

@ Richard Sears

What a great mnemonic! Your analysis also seems at least somewhat reminiscent of that in Li Xiaoding (1964) although without the "tea" comment. However, much like the recent discussion of 鬼 (http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=40954 ), I don't think it is ultimately correct.

Adam Smith said,

January 13, 2019 @ 12:39 pm

@Chris Button

Hi Chris, it's been ages. How are things? I don't disagree with any of your remarks. I tacitly adopted the reconstruction with medial (not necessarily infix) *r for div. ii because it is the one I am most familiar with, and enjoys the most currency. I don't know the reasoning behind Pulleyblank's alternative treatment, so have no reason to oppose it. Victor's original question was about the graphic distinction between 荼 and 茶 rather than the phonological reconstruction of the words in question. But regardless of which reconstruction is better, I'm inclined to agree with you that the two forms are "slightly divergent pronunciations of the same word", and their contrast in MC is the result of interdialectal loan, 文白异读, or something like that. More speculatively, I was wondering whether…

檟 *kra

葭荼 *kra-la

苦荼 *kha-la

茶 *lra

(reconstructions simplified)

… might be spellings for "divergent pronunciations of the same word". They all seem to be tea / bitter edible plant words, associated with one another in early lexical sources (in the sources quoted above). If they are indeed related, they variously point toward OC vowel *a, div ii vowel in MC, and perhaps a *kl or *kr onset in the source language. But, as I say, this is speculative, and I doubt whether there is enough evidence to pursue it very far.

Chris Button said,

January 13, 2019 @ 10:20 pm

@ Adam Smith

Great to hear from you and thanks for the comment. Well, I'm still "pretending" to be an academic (at least on LLog) and My "Derivational Dictionary of Chinese and Japanese Characters" is coming along excruciatingly slowly, but is still very much alive.

Regarding "divergent pronunciations", all I can say in terms of the onset is that the evidence points to a plain lateral in the source language as is clearly represented by 荼/茶. However, in terms of the coda (or lack thereof) I'm very interested in this comment from Victor Mair and Erling Hoh's book regarding shè 蔎:

My question is when would the original -t coda in 蔎 (along with -p and -k elsewhere) have debuccalised to -ʔ in Shanghai? My assumption, quite possibly wrong, is that it would have happened after the 9th century. If so, is it possible that we could actually be dealing with the same -k coda found in Written Burmese lak (as noted above) and some other languages?

Chris Button said,

January 15, 2019 @ 1:00 pm

I wonder if 檟 and 葭荼 might simply derive from 苦荼 as a compound noun "bitter leaf"?

Regarding a final -k, I speculated on the earlier "Caucasian Words for Tea" post (cited above) that the -k in Written Burmese "lak(phak)" (now pronounced /lə(pʰɛʔ)/) "tea(leaf)" might be connected to the -ʔ in the Mon-Khmer source *slaʔ "leaf". Although Old Burmese did have a glottalic final that became a tone category (ultimately from the same *-s as Chinese qu-sheng), its form as a subscript glottal suggest that already at the time of borrowing it might have been a glottalic co-articulation (modern day creaky tone) rather than an individual segment. As a result, perhaps WB -k was the next closest thing to MK -ʔ. It is notable that Mon-Khmer *slaʔ "spleen" gives Burmese sarak(rwak) (now pronounced /θəjɛʔ(jwɛʔ)/) "spleen" also with a *-k although in this case the *s- in the onset is also retained.