Kids today yesterday

« previous post | next post »

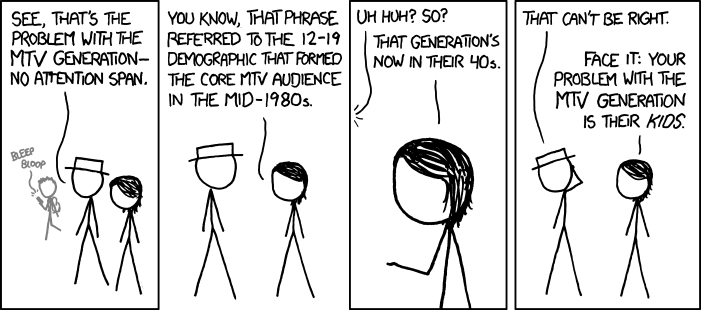

The most recent xkcd:

The mouseover title: "If you identified with the kids from The Breakfast Club when it came out, you're now much closer to the age of Principal Vernon."

The Breakfast Club, in case you happen to have missed it, was a 1985 movie about high-school detention.* And the guy who played Principal Vernon was born in 1939 and died in 2006 at the age of 67, so he was 45 or 46 in 1985; and someone who was 15 or 16 then would be 41 or 42 now, so Randall's guess turns out to be quantitatively exact pretty close.

Skipping a generation, the teens who identified with James Dean 30 years earlier in Rebel Without a Cause are now in their 70s. You can do the calculation yourself for Die Leiden des jungen Werthers (1774).

There are plenty of earlier cases where age-graded culture differences (or perceptions of such differences) have been perceived as decay. For some examples, see "Kids today", 3/11/2010.

On the other hand, there are also many cases where people think that "modern" linguistic or other cultural developments represent progress. One striking example is John Dryden's argument (in Defense of The Epilogue: or, An Essay on the Dramatick Poetry of the Last Age, 1672) that

… these absurdities, which [Jonson and Shakespeare] committed, may more properly be called the age's fault than theirs. For, besides the want of education and learning, (which was their particular unhappiness,) they wanted the benefit of converse […] Their audiences knew no better; and therefore were satisfied with what they brought. Those who call theirs the Golden Age of Poetry, have only this reason for it, that they were then content with acorns, before they knew the use of bread …

That particular passage deals with what Dryden reckons to be the implausibility of their plots, but he goes on to complain of their language:

But it is not their plots which I meant, principally, to tax; I was speaking of their sense and language; and I dare almost challenge any man to shew me a page together, which is correct in both.

And he starts the whole discussion in these terms:

It is … my part to make it clear, that the language, wit, and conversation of our age, are improved and refined above the last; and then it will not be difficult to infer, that our plays have received some part of these advantages.

In the first place, therefore, it will be necessary to state in general, what this refinement is, of which we treat; and that I think will not be defined amiss, An improvement of our Wit, Language, and Conversation; or, an alteration in them for the better.

To begin with Language. That an alteration is lately made in ours, or since the writers of the last age, (in which I comprehend Shakspeare, Fletcher, and Jonson) is manifest. Any man who reads those excellent poets, and compares their language to what is now written, will see it in almost any line. But, that this is an improvement of the language, or an alteration for the better, will not so easily be granted. For many are of a contrary opinion, that the English tongue was then in the height of its perfection; that from Jonson's time to our it has been in a continual declination; like that of the Romans from the age of Virgil to Statius, and so downward to Claudian: of which, not only Petronius, but Quintilian himself so much complains, under person of Secundus, in his famour Dialogue De Causis corruptae Eloquentiae.

But to shew that our language is improved, and that those people have not a just value for the age in which they live, let us consider in what the refinement of a language principally consists: that is, either in rejecting such old words or phrases which are ill sounding or improper, or in admitting new, which are more proper, more sounding, and more significant.

The reader will easily take notice, that when I speak of rejecting improper words and phrases, I mention not such as are antiquated by custom only; and, as I may say, without any fault of theirs. For in this case the refinement can be but accidental; that is, when the words and phrases which are rejected, happen to be improper. Neither would I be understood, when I speak of impropriety of language, either wholly to accuse the last age, or to excuse the present; and least of all, myself; for all writers have their imperfections and failings; but I may conclude in the general, that our improprieties are less frequent, and less gross than theirs. […] [M]alice and partiality set apart, let any man who understands English, read diligently the works of Shakspeare and Fletcher; and I dare undertake that he will find in every page either some solecism of speech, or some notorious flaw in sense: and yet these men are reverenced, when we are not forgiven. That their wit is great, and many times their expressions noble, envy itself cannot deny […] But the times were ignorant in which they lived.

The Epilogue being defended was part of his 1670 play The Conquest of Granada:

Fame then was cheap, and the first comer sped;

And they have kept it since, by being dead:

But, were they now to write, when criticks weigh

Each line, and every word, throughout a play,

None of them, no not Jonson in his height,

Could pass, without allowing grains for weight.

Think it not envy, that these truths are told;

Our Poet's not malicious, though he's bold.

'Tis not to brand them, that their faults are shown,

But, by their errours, to excuse his own.

If love and honour now are higher rais'd,

'Tis not the poet, but the age is prais'd.

Wit's now arriv'd to a more high degree;

Our native language more refin'd and free;

Our ladies and our men now speak more wit

In conversation, than those poets writ.

John Dryden, born in 1631, was 39 when The Conquest of Granada was first performed, and 41 when the Defense was published — the same age the fictional Breakfast Club kids would be today, and approaching the age of Principal Vernon (or of the actor playing him, anyhow).

In language as in other areas, it's clear that much age-associated meta-culture is related to such motives of self-justification — which is not to deny the existence of genuine historical change, independent of its evaluation as decay or progress.

* AB writes:

I feel the need to represent my generation (born 1971) and to take issue with your characterization of one of my favorite movies:

The Breakfast Club, in case you happen to have missed it, was a 1985 movie about high-school detention.

"High-school detention" was just the setting. The movie is about confronting and breaking down stereotypes, about (non-)conformity and rebellion, and about finding/choosing one's path along these different dimensions. Principal Vernon's character is particularly interesting and complex in this regard: he's the conformity enforcer, but he's also angry at what he feels he has to conform to himself.

All true. I should have added that if you haven't seen it, you definitely should do so. And if you haven't seen it in a while, you could find many worse ways to spend an evening than seeing it again.

Kylopod said,

November 6, 2011 @ 9:02 am

John Dryden, born in 1631, was 39 when The Conquest of Granada was first performed, and 41 when the Defense was published — the same age as Principal Vernon (or the actor playing him, anyhow).

It should be kept in mind that a 41-year-old was effectively "older" in 1631 than in 1985, because the average life span is much longer today (and not just because of decreased infant mortality).

J F Foster said,

November 6, 2011 @ 9:55 am

I thought "The Breakfast Club" was a radio program on weekday mornings hosted by Don MacNeil with Sam and Our Old Friend Aunt Fanny (fran Allison). And we MARCHED around the breakfast table, not shuffle slovenly.

GeorgeW said,

November 6, 2011 @ 10:08 am

J F Foster: Oh my goodness, vague memories from my youth.

Kylopod said,

November 6, 2011 @ 10:15 am

And, alas, the guy who played Principal Vernon died in 2006 at the age of 67, so he was 41 in 1985; and someone who was 15 then would be 41 now, so Randall's math is exact.

Paul Gleason, who played Principal Vernon, was born in May 1939, which means he was 45 when The Breakfast Club came out (in Feb. 1985), not 41.

[(myl) My mental arithmetic is crappy; not the first time, but here doubly so, because 67-(2006-1985) = 67-21 = 46. For the analogy with Dryden, I'll have to lean on your earlier comment that 41 was older in 1672 than it is today.]

bks said,

November 6, 2011 @ 10:23 am

Kylopod, life expectancy in the 17th century for a forty-year-old was about the same as it is today, which is the same as it was three thousand years ago:

"The days of our years are threescore years and ten; and if by reason of strength they be fourscore years,yet is their strength labor and sorrow; for it is soon cut off, and we fly away. "(Psalms 90)

Life expectancy, humans, planet earth: 69.2 years (Google)

–bks

Jerry Friedman said,

November 6, 2011 @ 10:31 am

I'd find it much easier to come to grips with the passage of time if it would stop occasionally and give me time to catch up.

@bks: I suspect the psalmist was talking about the maximum lifespan, not the mean.

Bob Krauss said,

November 6, 2011 @ 10:37 am

Interestingly, for members of an only slightly older generation (of which I am one), "The Breakfast Club" refers to a weekday morning radio show (remember radio?) hosted by Don McNeill. The show ran from 1933 to 1968. It featured a March Around the Breakfast Table.

Jon Weinberg said,

November 6, 2011 @ 10:37 am

Jeffrey Singman, in Daily Life in Elizabethan England, writes that while life expectancy at birth was about 48 years, "anyone who made it through the first 30 years was likely to live for another 30." The "forties and fifties were considered the prime of a man's life," and 60 marked the beginning of old age. That said, he also refers to estimates that more than 90% of the population died before age 60.

bks said,

November 6, 2011 @ 10:55 am

Jerry Friedman: even without adding Methuselah to the actuarial table, it would be hard to justify that interpretation as the psalm itself goes on beyond fourscore.

–bks

GeorgeW said,

November 6, 2011 @ 11:18 am

Jerry Feiedman & bks: One (and reasonable) translation of Ps 90:10:

"The span of our life is seventy years, or given the stength, eighty years . . ."

It seems clear that this is the expected maximum, not the mean.

Ian Tindale said,

November 6, 2011 @ 11:26 am

I always used to tell people to their surprise that we’re further away from punk and the Sex Pistols than punk and the Sex Pistols were away from Nazi Germany. Of course, that was back in the ’90s when I was saying that, so we’re now further away from that realisation for the first time than Bill Haley and the birth of Rock & Roll was from the end of WWII, probably, etc, and so on…

Nick Lamb said,

November 6, 2011 @ 11:45 am

bks, but Gleason was born in the US, where human life expectancy at birth is today 77.9 (and will probably continue to rise, absent political meddling). As previously explained, the ongoing rise is no longer mainly due to reduced infant mortality. At birth Gleason (a US male born in 1939)'s life expectancy was about 61.1 years. His equivalent born in 1970, had a life expectancy of 67.0 years. That's almost a six year difference.

There are a bunch of causes. Gleason's peers tended to drink and smoke excessively, while their counterparts have been endlessly told not to take up smoking, or give it up if they have, and to drink only moderately and infrequently; Health care access has improved, moderately over this period in the US; Improved diet, overall across the US meals are slightly healthier than they were; Medical breakthroughs have made some once incurable ailments associated with age curable, and increased survival periods for numerous cancers and other diseases.

bks said,

November 6, 2011 @ 12:14 pm

Nick: So three thosand years ago it was 70-80 and now it's 77. And, btw, it has started decreasing in the USA:

http://articles.baltimoresun.com/2011-06-15/news/bs-ed-life-expectancy-20110615_1_life-expectancy-health-care-health-inequalities

GeorgeW: not sure where you get "maximum" from, but it reads as "typical" to me. One does not give two different figures when speaking of a maximum.

–bks

Andrew (not the same one) said,

November 6, 2011 @ 12:42 pm

As well as infant mortality, one has to consider the greater risk of violent death in many past ages, and also death in childbirth. Of course 70 is not a mean in the strict mathematical sense – who would be calculating that? – but it can be read as 'age to which one might reasonably be expected to live, barring violence, death in childbirth, sudden irruptions of plague, etc.'. A 'normal' life could be near what it is today, even though far fewer people lived a 'normal' life.

octopod said,

November 6, 2011 @ 12:46 pm

Few things irritate me as profoundly as the misunderstanding that because the mean lifespan was (let's say) 45 years, people were old when they were 45. That would require significant changes in human biology between then and now, and just doesn't make any goddamn sense.

To reiterate: just because death from disease or accident was higher at each age, especially early ages, does not mean that people got old faster. The average lifespan of soldiers in aggregate is probably lower than that of farmers, but that doesn't mean soldiers age faster than farmers!

Do people who say this just not understand how averages work, or what?

Kylopod said,

November 6, 2011 @ 1:11 pm

@octopod

The point isn't that people's biology was different but that society may have viewed them as being at a more advanced stage of life than people of the same age today, due to the differences in life expectancy.

[(myl) For example, Dryden was elected to the Royal Society in 1662, at the age of 31. (He was expelled in 1666 for non-payment of dues, but still…) He became Poet Laureate in 1667, when he was 36. In comparison, the last 8 British P.L.'s have acquired that status at the ages of 61 (Alfred Austin), 69 (Robert Bridges), 52 (John Masefield), 64 (Cecil Day-Lewis), 66 (John Betjeman), 54 (Ted Hughes), 47 (Andrew Motion), and 54 (Carol Ann Duffy). I suspect that a survey of recently-elected F.R.S. would show something similar.]

Mark F. said,

November 6, 2011 @ 1:16 pm

Dryden's argument about language seems laughable now — by what measure could he declare an old word or phrase "improper"? It is as if he thought there was a Platonic ideal of English that was slowly being discovered.

But his failure to make a case that English was improving doesn't make it logically incoherent to think that a language could improve. There is this assumption among linguists that every language is sufficient unto its task, and it's a helpful antidote to the nationalistic temptation to declare one's own language the best.

But you could imagine that some languages might be easier to hear correctly over background noise, or less likely to lead to misunderstanding, or perhaps easier for speakers of unrelated languages to learn. Supposedly there is evidence that Chinese makes it easier to remember slightly longer sequences of numbers, because the names for the numbers are shorter, but I don't know how much credence to give to that.

My impression is that the assumption of language equality is mostly right, because languages are so malleable that felt needs can be remedied relatively quickly. But I don't think we are compelled by the facts to view all changes in our language as neither good nor bad. Maybe sometimes languages do change for the worse. Or better.

hector said,

November 6, 2011 @ 2:37 pm

@ myl: In a society in which higher education is restricted to the relatively few, and class connections matter, advancement of the highly talented can be quite rapid.

And the fact that Dryden was a strong supporter of the newly triumphant forces of the Restoration didn't hurt, either.

[(myl) True enough. But whatever the exact reasons — lower life expectancy, greater social inequality, smaller society, chaotic times — Dryden at 41 had the life-stage attributes that today would usually be characteristic of someone older than that.]

marie-lucie said,

November 6, 2011 @ 2:39 pm

Old: besides the improvements in diet and in infant and maternal health, the fact that most infectious diseases either have disappeared through vaccination or are treatable, and that many conditions can be corrected or made tolerable through operations and drugs, all of which have led to increased survival and longevity, the appearance of people has also been substantially altered through major improvements in dentistry. It is now rare to see Western people obviously missing some or all of their teeth, or even with seriously crooked or rotten teeth. Dental problems also make it difficult to eat properly, whether from pain or from being unable to masticate hard foods.

Coby Lubliner said,

November 6, 2011 @ 2:45 pm

In the late 17th century disputes over whether the "Moderns" were better or worse than the "Ancients" (whether those of antiquity or a more recent age) were a popular intellectual pursuit. Those who favored the contemporary culture, like Dryden, often did so as a way of flattering the vanity of the current monarch (Charles II, Louis XIV and their ilk).

GeorgeW said,

November 6, 2011 @ 3:49 pm

@bks: "not sure where you get "maximum" from, but it reads as "typical" to me.

I would agree with "typical," but length of life not terminated prematurely. I doubt if the psalmist was giving a calculation of life expectancy factoring in infant mortality, death due to war, accident, disease and the like during mid life.

Rob said,

November 6, 2011 @ 7:52 pm

@Ian Tindale

I sometimes show my students a clip of JFK's speech about the Apollo Program at Rice University. It's always slightly jarring to hear him talking about flying the Atlantic '35 years ago'. Then I realise that JFK was closer to Lindbergh than we are now to Apollo 11. And then that the kids I'm showing the clip to weren't alive when the Berlin Wall came down. And then I need a little sit-down.

Adam said,

November 7, 2011 @ 4:54 am

Wasn't Dryden the one who first proscribed preposition-stranding?

Nick Lamb said,

November 7, 2011 @ 5:22 am

octopod, in studies of health care personnel perceived age is inversely correlated to time to death, even when controlled for age since birth. ie the older you look to a doctor or nurse, the sooner you are likely to die. It's not a big stretch to think the same applies more vaguely to the entire population, since we don't specifically train health care professionals to think this way.

bks, you've shifted your position. The people who wrote that poetry had no idea America even existed, let alone what the male life expectancy at birth was there at the time of its writing. (I don't for one moment think that's what they were writing about, but you insist that it was, so…) Yes, America's life expectancy is rather disappointing for a powerful industrialised country, it's not in the top 10 last I looked.

We have drifted very far from the topic. I suspect Randall included people in their later teens in his group who identified with "the kids". The actors were not as much older than their characters as in some Hollywood movies, but some were in their 20s, I'd guess anyone still in education and living with their parents could identify with the hopes & fears of the high school students in this movie. So that pushes the number closer in some cases.

J.W. Brewer said,

November 7, 2011 @ 9:23 am

As a counterexample, in the history of linguistics, Sir William Jones was 39 when he delivered his famous speech hypothesizing the existence of PIE; Chomsky was 28 when Syntactic Structures was published. That the history of linguistics from 1957 to the present *feels* like a longer span of time than the prior history from 1786 to 1957 may be an illusion of sorts . . .

[(myl) A counterexample to what? Sir William Jones had already in his early 30s been a circuit judge in Wales, and spent a significant period in Paris working with Benjamin Franklin to try to negotiate an end to the American Revolution. He went to India because he was appointed as a judge on the Supreme Court of Bengal in 1783 (at the age of 37), and he studied Sanskrit so that he could read and understand the local legal system. Thus his trajectory through life was similar, at least abstractly, to Dryden's — both were appointed to relatively important positions in their 30s.]

Dan H said,

November 7, 2011 @ 10:16 am

This comic lost me in panel 1, because my initial reaction was something like "hang on, nobody complains about the MTV generation any more." Certainly I can't imagine anybody, however old, using the phrase to describe an iphone-wielding, twitter-using, hoodie-wearing modern teenager.

It just felt completely jarring, like calling them "beatniks".

Jonathan said,

November 7, 2011 @ 10:37 am

I still am occasionally self-astonished by the fact that I was born 11 years after the end of WWII, an event which seemed in my youth to have taken place in the infinitely long-ago past and now I realize was roughly as far before my birth as 9/11 is now.

S. Norman said,

November 7, 2011 @ 11:19 am

Yes, a "movie is about confronting and breaking down stereotypes" that showed that the punk rock chick can go out with the jock as long as she tarted herself up and stopped looking soo different.

J. W. Brewer said,

November 7, 2011 @ 12:11 pm

The Archbishops of Canterbury during Dryden's lifetime were aged 59, 77 (arguably an outlier due to the disruption of the Cromwell era), 64, 60, 60 & 58 at time of appointment (where wikipedia's lack of specificity made it impossible to determine whether office was assumed before or after the candidate's birthday that calendar year I have consistent used the lower of the two possible ages). The most recent six (including the present incumbent) were 58, 56, 55, 59, 55 & 52 at time of appointment. It's not clear that that's a better proxy for how the English establishment viewed the age/authority nexus across the centuries than the Poet Laureateship, but it's also not clear that it's a worse one. I think what age counts as "old," or what age counts as a surprising age to have reached a particular professional status, or even what age qualifies one to complain grumpily about the shortcomings of These Darn Kids may vary much more with context and field than with century. Was literary/artistic fame such as Dryden's dramatically more of a young man's game in the 17th century than the 20th? What well-known English-languge poet of the 20th century was not already famous by 35, if not 30? The ossified old-fart hegemony the Sex Pistols and their contemporaries rose up against in their particular field of aesthetic endeavor c. 1977 was comprised of old farts in their mid-thirties.

Andrew (not the same one) said,

November 7, 2011 @ 12:45 pm

I think it's arguable that both the Poet Laureateship and the FRS were rather different things in Dryden's time from what they are now; they are now definitely honours, whereas in those days the laureateship was a way of supporting someone who did useful propaganda work, and the Royal Society was a society of scientists and patrons of science, actually involved in organising experiments, and admitting those who supported their work.

Andy Averill said,

November 7, 2011 @ 12:52 pm

I'll stick with Tom Lehrer's observation on turning 38: It's a sobering thought that when Mozart was my age, he'd been dead for two years.

S Hawkins said,

November 7, 2011 @ 4:09 pm

@ S. Norman "the punk rock chick can go out with the jock as long as she tarted herself up and stopped looking soo different."

And the nerd has no romantic interest, but ends up doing the writing assignment for everyone else.

Dr. Decay said,

November 8, 2011 @ 6:22 am

Is anybody as annoyed as I am that Dryden's beautifully written screed contains not a single example of a "solecism of speech, or some notorious flaw in sense" against which he rants?

Ken Brown said,

November 8, 2011 @ 6:33 am

@Andrew (not the same one) – yes. In the 17th & early 18th century the Laureateship was really a PR post. Later in the 18th century it went to friends of the ruling party and to men known as critics or commentators on poetry rather than poets, including some pretty plodding hacks.

But since then its been more of a Lifetime Achievement Award – an attempt to name "The Nation's Greatest Poet" – or at least "The Nation's Favourite Poet" which isn't quite the same thing.

And poets had often been in government service – Dryden and Marvell both worked for Milton and famously processed with him at Cromwell's funeral. The density of great poets in London then must have been astonishing – even more famously in earlier years Milton had lived in a flat above the pub that Jonson and Shakespeare and their theatre friends (probably including Fletcher) drank in and Donne lived fifty yards away at the end of the street. Of course they were the generation of poets that Dryden is praising with faint damns.

@Mark F: "Dryden's argument about language seems laughable now — by what measure could he declare an old word or phrase "improper"? It is as if he thought there was a Platonic ideal of English that was slowly being discovered."

I think Dryden knew that. Its one of the things he meant by:

"The reader will easily take notice, that when I speak of rejecting improper words and phrases, I mention not such as are antiquated by custom only; and, as I may say, without any fault of theirs. For in this case the refinement can be but accidental; that is, when the words and phrases which are rejected, happen to be improper."

You don't get to be a great poet without a bit of studied ambiguity.

Janice Byer said,

November 8, 2011 @ 10:43 pm

Norman, schoolgirls "tarting" themselves up, when down with senior slump or head over heels with a crush, was so customary in parts of America last century, that it could explain why what impressed you I don't even remember. I do remember trying hard to tart up and out of my good-girl reputation. Are you sure you aren't confusing Breakfast Club with Grease?

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uCK55mUA2vs&feature=related

Tom said,

November 13, 2011 @ 7:39 am

To me, irrespective of the historic changes noted between Dryden's time and ours, there are quantitative approaches to understanding the differences between, e.g., the MTV Generation in the 1980s and today. It's like untangling age, period and/or cohort effects in longitudinal research. Age effects refer to attitudes or behaviors that are specific, for instance, to teens. Period effects refer to attitudes or behaviors that are specific to the times or cultural zeitgeist while cohort effects are things that are shared by a group, e.g., baby boomers, as they move through time and space. As it happens, these are thorny statistical issues but the xkcd comic captures them nicely.

[links] Link salad changes the clocks | jlake.com said,

November 29, 2011 @ 4:36 am

[…] Kids today yesterday — Language Log on xkcd, John Dryden and the decline of standards in kids today. […]