"Words for snow" watch

« previous post | next post »

It's been a while since we've rounded up public appearances of the old "Eskimo words for snow" myth. Here are a few recent examples that have been sent in to Language Log Plaza.

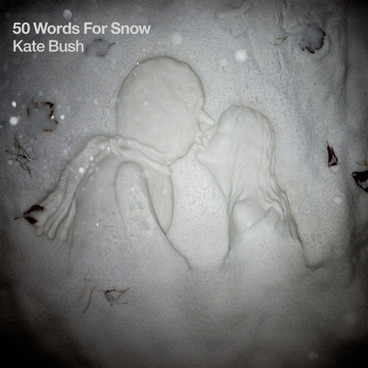

Item #1: The singer-songwriter Kate Bush will be releasing a new album on Nov. 21 with the title (sigh) 50 Words for Snow. That's also the name of a song on the album, and some other tracks are similarly snow-themed ("Snowflake," "Snowed in at Wheeler Street"). It's unclear at this point exactly how Eskimos will figure into Bush's songwriting, but it's safe to say they'll be in there somewhere. It's perhaps also a telling sign that the album features a guest appearance from Stephen Fry, he of "Fry's Planet Word."

Item #1: The singer-songwriter Kate Bush will be releasing a new album on Nov. 21 with the title (sigh) 50 Words for Snow. That's also the name of a song on the album, and some other tracks are similarly snow-themed ("Snowflake," "Snowed in at Wheeler Street"). It's unclear at this point exactly how Eskimos will figure into Bush's songwriting, but it's safe to say they'll be in there somewhere. It's perhaps also a telling sign that the album features a guest appearance from Stephen Fry, he of "Fry's Planet Word."

[Update, 10/15: As pointed out by Matt in PDX, Fry has actually debunked the "words for snow" myth on the game show QI — see here for a transcript. So perhaps he set Kate straight on this.]

[Update, 11/14: See this followup post for more on the title track.]

Item #2: The Atlantic has published an excerpt of The Wage Slave's Glossary, "a fun dictionary of modern office idioms and new economy jargon by Joshua Glenn, Mark Kingwell, and the cartoonist Seth." You can probably guess that the excerpt is presented in classic snowclone style:

Alaskans have more than 100 words for snow, as legend has it. So it's only appropriate that Americans, who work longer hours with fewer paid breaks than almost any other developed country, would have hundreds of words for working. Or, not working. In our current crisis, consider the panoply of terms for being let go from work: there are layoffs, furloughs, firings, redundancies, non-renewals, partings, breaks, and, finally, funemployment. It's exhausting just to count the synonyms.

Item #3: It's not all misinformation out there on the snow-word front. Positive reviews have been coming in for the new book by David Bellos, Is That a Fish in Your Ear? Translation and the Meaning of Everything (Faber & Faber). Some of the reviews have noted that Bellos debunks the snow-word myth in Chapter 14, "How Many Words Do We Have for Coffee?" Here's a sampling from that chapter:

The number of New Yorkers who can say "good morning" in any of the languages spoken by the Inuit peoples of the Arctic can probably be counted on the fingers of one hand. But in any small crowd of folk in the city or elsewhere you will surely find someone to tell you, "Eskimo has one hundred words for snow." The Great Eskimo Vocabulary Hoax was demolished many years ago, but its place in popular wisdom about language and translation remains untouched. What are interesting for the study of translation are not so much the reasons this blooper is wrong but why people cling to it nonetheless.

People who proffer the factoid seem to think it shows that the lexical resources of a language reflect the environment in which its native speakers live. As an observation about language in general, it's a fair point to make — languages tend to have the words their users need and not to have words for things never used or encountered. But the Eskimo story actually says more than that. It tells us that a language and a culture are so closely bound together as to be one and the same thing."Eskimo language" and "the [snowbound] world of the Eskimos" are mutually dependent things. That's a very different proposition, and it lies at the heart of arguments about the translatability of different tongues.

Bellos goes on to provide a quick overview of how the concept of linguistic relativity was developed and then was subsequently watered down into the snow-word myth. He argues that the myth gets repeated because of the misguided notion that "the multiplicity of concrete terms 'in Eskimo' displays its speakers' lack of the key feature of the civilized mind — the capacity to see things not as unique items but as tokens of a more general class." He concludes:

If you go into a Starbucks and ask for "coffee," the barista most likely will give you a blank stare. To him the word means absolutely nothing. There are at least thirty-seven words for coffee in my local dialect of Coffeeshop Talk (or tok-kofi, as it would be called if I lived in Papua New Guinea). Unless you use one of these individuated terms, your utterance will seem baffling or produce an unwanted result. You should point this out next time anyone tells you that Eskimo has a hundred words for snow. If a Martian explorer should visit your local bar and deduce from the lingo that Average West Europeans lack a single word to designate the type that covers all tokens of small quantities of a hot or cold black or brown liquid in a disposable cup, and consequently pour scorn on your language as inappropriate to higher forms of interplanetary thought — well, now you can tell him where to get off.

In a footnote, Bellos cites the standard references on debunking the myth: Laura Martin's "Eskimo Words for Snow: A Case Study in the Genesis and Decay of an Anthropological Example" (American Anthropologist, 1986) and Geoff Pullum's The Great Eskimo Vocabulary Hoax (Univ. of Chicago Press, 1991).

(Hat tips to Stan Carey and Nancy Friedman.)

[Update, 10/15: Via Brain Pickings, here is a book trailer for Is That a Fish in Your Ear?, featuring an interview with Bellos accompanied by kinetic typography.]

Marc Leavitt said,

October 14, 2011 @ 2:27 pm

I knew you wouldn't snow me!

John Emerson said,

October 14, 2011 @ 2:31 pm

The Martian explorer would also conclude that "tall" is the American word for large, except that there is no longer a word for small (though "short" used to work during the prehistoric period), so that "tall" is also the new word for small.

J. W. Brewer said,

October 14, 2011 @ 2:32 pm

To be fair to the mythmongers, is it really true that the "X words for Y" snowclone is typically accompanied these days by the claim "but no word for Y-in-general"?

Carrie Gillon said,

October 14, 2011 @ 2:41 pm

@JW Brewer:

And, anyway, Inuktitut does lack a general term for 'fish', for example. I'm not sure what this means, however.

Devon Strolovitch said,

October 14, 2011 @ 2:47 pm

"If you go into a Starbucks and ask for "coffee," the barista most likely will give you a blank stare. To him the word means absolutely nothing."

Not sure I agree with that one. I would expect a reply something to the effect of, "What size?" Seems to me the barista could understand me to have meant some basic, unmarked, prototypical beverage in the category 'coffee' — what someone else might qualify with 'regular' (i.e. drip / brewed coffee).

Dennis Paul Himes said,

October 14, 2011 @ 2:55 pm

English lacks a general word (at least in common usage) for "frog or toad". Likewise for "dragonfly or damselfly".

Dave Ferguson said,

October 14, 2011 @ 3:00 pm

The Canadian writer Frank Macdonald, who's also my cousin, tells of a coal-mine manager, Tom Chew, who used to patronize my grandfather's store. Tom would ask for chocolate syrup stirred into milk, not a drink people were familiar with back then in a small Cape Breton Island town. Realizing the combination was cheaper than a milkshake, people began asking at the soda fountain for a Tom Chew; Frank remembers doing this himself when young.

From time to time, people "from away" would return home with tales about ignorance in the wider world: “I walked into a drug store in Toronto and ordered a Tom Chew and they didn’t know what the hell I was talking about.”

Andrew (not the same one) said,

October 14, 2011 @ 3:39 pm

It's not all misinformation out there on the snow-word front.

I don't see any misinformation at all. The Atlantic says 'as legend has it'. Ms. Bush makes no assertion (that we know of so far, at least); she just adopts a well-known phrase as a title.

[(bgz) I acknowledge that I'm being a tad unfair by prejudging Ms. Bush before the release of her album. But hedging widely circulated misinformation with "as legend has it" still strikes me as misinformation. YMMV.]

David said,

October 14, 2011 @ 3:44 pm

Snowboarders have 100 words for snow.

Kathleen said,

October 14, 2011 @ 4:34 pm

I did not realize that the claim "x has 100 words for y" was often accompanied by the derogatory implication that "those simpletons can't see that all those things are basically the same."

When I have seen "x has 100 words for y," the implication has usually been "Oh, those other cultures! So thoughtful! So observant! How poetic and attentive they must be to notice so many wonderful differences among phenomena that we dull Westerners clump together!"

Perhaps this is just two sides of the same coin. Those others — they just aren't like us!

Aaron Toivo said,

October 14, 2011 @ 4:58 pm

@ Dennis Paul Himes:

My go-to example is usually cattle, for which there are more words I can rattle off on a moment's notice – cow, heifer, bull, ox, calf, cattle, bovine – and point out that not one of them refers to an individual of that species without specifying further information at the same time. This has worked better for me and in less time, when countering the Eskimo legend, than explaining why word counts are unimportant ever did.

maidhc said,

October 14, 2011 @ 5:34 pm

I think it would be safe to say that people who spend a lot of time dealing with a particular thing would make finer differentiations about different types of the thing than people who don't. Skiers have more words for different types of snow, surfers have more words for waves, nerds have more words for computers. It's an occupation-based quality that would be true in any language.

That said, English usually has a lot of ways to say the same thing even when it's not really necessary.

BeSlayed said,

October 14, 2011 @ 8:12 pm

@John Emerson: And the disappearance of the word "small" would be confirmed by visiting any pizza place.

Alon said,

October 15, 2011 @ 1:32 am

Seems to me the barista could understand me to have meant some basic, unmarked, prototypical beverage in the category 'coffee' — what someone else might qualify with 'regular' (i.e. drip / brewed coffee).

But there may not be an unmarked prototype. Ask for coffee in Israel and you'll be asked whether you want shahor (i.e., Turkish coffee), Nes (i.e., instant) or, if you are in a fancy place, espresso. Ordering 'coffee' is as pragmatically unfelicitous as ordering 'meat' or 'fruit' in a restaurant.

As a side note, I've long been fascinated by the cultural variability of the prototype. Ask for plain 'café' in the Americas, and you will get a 1oz cup of black espresso. Ask for plan 'café' in Spain, and you will get a 5oz cup of au lait.

Jayarava said,

October 15, 2011 @ 3:01 am

yes, but the English do have 100 words for rain… ;-)

Matt in PDX said,

October 15, 2011 @ 3:14 am

Speaking of Stephen Fry… he's come in for some (justified) griping on Language Log recently. But it's worth mentioning that the quiz show he hosts, QI, debunked the Eskimo snow myth several series ago. As I recall they gave the number of snow words cited in the Pullum essay and its sources, so someone on their research staff was doing his or her homework.

[(bgz) Thanks! A transcript of the show is here. I've added an update to the post.]

Dan said,

October 15, 2011 @ 4:34 am

Starbucks' coffee sizing has nothing on the olive industry. http://www.sizes.com/food/olives.htm

JC Dill said,

October 15, 2011 @ 9:30 am

Although I haven't read the book, from the excerpts above it looks like Bellos missed a golden opportunity. I can imagine the quotes now:

~ "Starbucks has 37 words for coffee." (David Bellos explains why Eskimos don't really have 100 words for snow in "Is That a Fish in Your Ear? Translation and the Meaning of Everything.")

Somehow, "There are at least thirty-seven words for coffee in my local dialect of Coffeeshop Talk (or tok-kofi, as it would be called if I lived in Papua New Guinea)." just doesn't have the same punch to it.

Lektu said,

October 15, 2011 @ 6:32 pm

Regarding the idea that some peoples are too primitive to have words denoting categories, behold a fragment of "Martian Oddissey" (Stanley G. Weinbaum, 1934), a very influential early "masterpiece" of science-fiction. The protagonist, and first-person narrator, is describing an alien's language, so:

"It set me wondering if perhaps his language wasn't like the primitive speech of some earth people—you know, Captain, like the Negritoes, for instance, who haven't any generic words. No word for food or water or man—words for good food and bad food, or rain water and sea water, or strong man and weak man—but no names for general classes. They're too primitive to understand that rain water and sea water are just different aspects of the same thing."

Even considering the 75+ years, the wildly patrozining "Negritoes" and the fact that several quite different linguistic families are lumped together as if they were a single language still makes me cringe.

The story is quite engaging nonetheless, if more than a little outdated. And it was Weinbaum's first SF history, and he was dead a year later at 33, so it's hard to judge him too harshly.

hector said,

October 15, 2011 @ 7:26 pm

@Devon Strolovitch:

Depends on the Starbucks. I once was in a Borders (or was it Barnes & Noble) in Bellingham, Washington, and asked the young woman at the Starbucks counter for a single shot of espresso. She gave me a bewildered, hesitant look, as if her brain couldn't quite compute what I had just said, so I had to repeat myself. I can only assume she had never had any one order a coffee that wasn't somehow sweetened, milkified, whip-creamed, cinnamonized or otherwise adulterated.

In the big city, on the other hand, there's no hesitation whatsoever to such an order.

Daniel Barkalow said,

October 15, 2011 @ 8:50 pm

I have a somewhat futile hope that Kate Bush, on the album, actually uses 50 different English words to denote snow. I think it would be possible, as 50 isn't really that large a number, she seems to be on that topic the whole time, and there are plenty of words which directly describe characteristics but would in the proper context be understood to refer to a particular mass of snow.

DJ said,

October 15, 2011 @ 9:40 pm

@Kathleen: That's been my feeling, too.

jwinchina said,

October 17, 2011 @ 4:59 am

I did not realize that the claim "x has 100 words for y" was often accompanied by the derogatory implication that "those simpletons can't see that all those things are basically the same." When I have seen "x has 100 words for y," the implication has usually been "Oh, those other cultures! So thoughtful! So observant! How poetic and attentive they must be to notice so many wonderful differences among phenomena that we dull Westerners clump together!"

This was always my reaction as well. With a deep love for words, I am generally envious of anyone who seems to have more ways to say something than I have in my own language, concluding that it must be easier for them to be more descriptive when discussing that topic than I could ever be. I tend to feel "sorry" for people with less words – like less basic color words to choose from. All this of course is just a "gut reaction," stemming largely from forgetting that every language has ways of combining words to form nuances that are just as descriptive as the "one hundred" choices another language may have to choose from.

In terms of the way we use language to cluster or differentiate, however, I know in my case that my view of pink was forever changed when I learned the Chinese term "light red," and had to admit that, indeed, pink was on the spectrum of shades of red. (Which I technically knew, but never thought of pink as in the same "color group" as red until learning Chinese.)

Caio said,

October 18, 2011 @ 12:29 pm

Here (http://tinyurl.com/3fjvfdf), Lera Boroditsky talks about one of the sun-oriented people Bellos mentioned. They're called the Thaayorre and they live in Australia. Boroditsky starts talking about them on Chapter 9, but the whole talk is great.

Mary J. said,

October 18, 2011 @ 12:47 pm

[Quote]English lacks a general word (at least in common usage) for "frog or toad. [/Quote]

I would say that amphibian actually is quite common usage.

aohawthorn said,

October 19, 2011 @ 9:24 am

@Mary J.: Yes, but that category also includes salamanders, newts, etc. The point, I think, is that the members of the order Anura – frogs and toads – resemble one another so closely that we could very reasonably have one common (non-scientific) word that referred to both – but we don't.

Compare the case of hares and rabbits. "Hare," I think, is slowly falling out of common usage (at least in the northeast U.S.), and "rabbit" is taking over as a general term for Leporidae. The same thing isn't happening to frogs and toads, though.

Language is wildly inconsistent in its specificity when referring to taxonomical categories. "Spider" is a distinction at the level of order, while "Dingo" refers to a sub-species. And since either one could eat my baby, I don't know what factors motivate the distinction.

Lane said,

October 19, 2011 @ 12:24 pm

I never order anything but "a small coffee" in Starbucks. They never fail to get my order right, either: 12 ounces of drip/filter coffee. I don't use their stupid "tall" and nobody misunderstands; I don't specify filter and indeed I get (I love this description) "unmarked" coffee, because in America filter coffee is unmarked. Your mileage would certainly vary; in Italy you'd probably get an espresso if you asked for "un caffe`", right?

The "Inuit *do so* have lots of words for snow" position still has its defenders, notably K. David Harrison of Swarthmore, of The Last Speakers book and The Linguists movie fame.

Mark Halperin, rather less trained in linguistics (in fact he hates all of you, and me) also claims, in Language and Human Nature, to have found experts in Inuit attesting to a blizzard (sorry) of lexemes for snow/ice.

Lane said,

October 19, 2011 @ 12:26 pm

Sorry, that would be Mark Halpern, the prescriptivist, not Mark Halperin, the political pundit.

[(myl) And neither Mark Halpern the prescriptivist nor Mark Halperin the political pundit is Mark Helprin the novelist (who confusingly has also been a political columnist at times).

As I noted here, someone who perhaps should have known better once formed the impression that I was simultaneously at least two of these other Marks, or more specifically that I had written Winter's Tale and was a political analyst for Time Magazine. ]

Lane said,

October 19, 2011 @ 2:55 pm

At least they didn't think you were Mark Halpern.

Mark Halpern said,

November 12, 2011 @ 4:45 pm

Once again I followed a list returned by Google — this time when I was searching for reviews of Bellos' book — to find that my name was being bandied about at LangLog. First, my congratulations and thanks for troubling to get my name right, and distiguishing me from the others with similar names. But Lane seriously distorts what I wrote n my Language & Human Nature; I did not base my claim about the number of words for snow on "some experts in Inuit"; I formed a list of snow words from various Eskimo languages, then submitted it to the foremost authorities on Eskimo languages (names and affiliations given), who approved it. Read that section of my book, then tell me why I'm wrong, if you can. I know myth-busting is fun, but it's no substitute for scholarship.

Gary Lupyan said,

November 15, 2011 @ 6:37 pm

I invite LanguageLog-ers to read through a paper I published a few years back showing that, in fact, having a word facilitates the categorization process. The implication is that learning a language that has a word for something facilitates the formation of the concept.

Lupyan, G., Rakison, D.H., & McClelland, J.L. (2007). Language is not just for talking: labels facilitate learning of novel categories. Psychological Science 18(12): 1077-1083.

http://sapir.psych.wisc.edu/papers/lupyan_rakison_mcClelland_2007.pdf

Bellos misses this point entirely, saying things like, if a language doesn't have a word for something and its speakers need to talk about it, they'll simply make one up. This may be true in the long-run, but an individual speaker does not have the luxury to just make up a word. Learning a language that makes the word available facilitates learning a category. Put another way: take two populations who are given the same amount of experience with varities of snow (or with anything, for that matter).

Give one of them a label for different snow varieties. That group will not only communicate more easily (this is obvious), but will come to learn the categories more quickly (this is what the paper cited above is all about).