The curious specificity of speechwriters

« previous post | next post »

Clark Whelton ("What Happens in Vagueness Stays in Vagueness: The decline and fall of American English, and stuff", The City Journal, Winter 2011) has an unusually precise idea about when American English went to the dogs:

[It] began in the 1980s, that distant decade when Edward I. Koch was mayor of New York and I was writing his speeches. The mayor’s speechwriting staff was small, and I welcomed the chance to hire an intern. Applications arrived from NYU, Columbia, Pace, and the senior colleges of the City University of New York. I interviewed four or five candidates and was happily surprised. The students were articulate and well informed on civic affairs. Their writing samples were excellent. The young woman whom I selected was easy to train and a pleasure to work with. Everything went so well that I hired interns at every opportunity.

Then came 1985.

And he also has an unusually specific theory about what went wrong: it was the triumph of linguistic childishness.

I was baffled by what seemed to be a reversion to the idioms of childhood. And yet intern candidates were not hesitant or uncomfortable about speaking elementary school dialects in a college-level job interview. I engaged them in conversation and gradually realized that they saw [this] not as slang but as mainstream English. At long last, it dawned on me: [This] was not a campus fad or just another generational raid on proper locution. It was a coup. Linguistic rabble had stormed the grammar palace. The principles of effective speech had gone up in flames.

Finally, Mr. Whelton has a overall diagnosis of the problem with immature language: it's vague and lacking in details:

I recently watched a television program in which a woman described a baby squirrel that she had found in her yard. “And he was like, you know, ‘Helloooo, what are you looking at?’ and stuff, and I’m like, you know, ‘Can I, like, pick you up?,’ and he goes, like, ‘Brrrp brrrp brrrp,’ and I’m like, you know, ‘Whoa, that is so wow!’ ” She rambled on, speaking in self-quotations, sound effects, and other vocabulary substitutes, punctuating her sentences with facial tics and lateral eye shifts. All the while, however, she never said anything specific about her encounter with the squirrel.

Uh-oh. It was a classic case of Vagueness, the linguistic virus that infected spoken language in the late twentieth century. Squirrel Woman sounded like a high school junior, but she appeared to be in her mid-forties, old enough to have been an early carrier of the contagion. She might even have been a college intern in the days when Vagueness emerged from the shadows of slang and mounted an all-out assault on American English.

So up to and including the class of 1984, American youth were articulate and well informed, able to present particular facts in proper English. In contrast, those who graduated from college in 1985 and later have abandoned the standard formal language in favor of an infantilized idiom whose key characteristic is its lack of specificity.

There are several odd things about the theory behind this amusing jeremiad. One is the notion that (linguistic) maturity corresponds to specificity. In fact, the narratives of real children are typically full of detail. The use of appropriate summarizing abstractions develops later, as I understand it; and the ability to speak at length without saying anything concrete at all is mastered fully only by mature politicians and their speechwriters.

But the oddest thing, I think, is the temporal specificity. Apparently Mr. Whelton came across a bad patch of interns in 1985, and inferred that this was due to a shockingly sharp generational change (rather than, say, the day of the week or the ambient weather). But (somewhat better documented) claims of (somewhat less sharp) generational changes in writing ability don't start with the college class of 1985. Thus Daniel J. Dieterich ("The Decline in Students' Writing Skills", College English 38(5): 466-472) interviewed two experts in college writing instruction:

Q: Are student writing skills declining?

LUTZ: I think so. We have been giving placement tests to entering freshman students for five years now, and each year the composite scores have declined. The test is composed of the Houghton Mifflin College English Placement Test, a standardized writing test, and an essay test which is graded by a faculty member of the English department and by a second independent grader if the first grader has any doubts whatsoever about how the paper should be graded. Scores have been going down disastrously across the board, both for students coming from very good high schools and for students from very bad high schools. There are other indications of this decline as well. Fordham, for example, now runs a large remedial writing program. According to the ADE Bulletin, the University of Chicago also now runs a remedial program. And Harvard has just instituted the position of Director of Expository Writing Programs. I think someone has called it "remedial writing for the advantaged student."

WHITE: I do think such a decline has taken place. I think every observer American education is aware of that, and that evidence for it is in everyone's experience, in test scores, and in the generalized concern among faculties-by no means only English faculties-about the obvious signs of decline. There are several national examinations which have kept records on scores and which show consistent declines over the last couple of decades. What has brought the decline home to me personally is the fact that my own freshman composition textbooks, which were once widely used in freshman composition courses, now seem to be used often in advanced composition courses. To me that is a pretty telling indication.

The year of the interviews? 1977, before Ed Koch was elected to his first term as Mayor of New York.

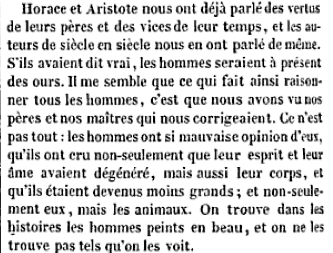

A few years earlier, we find that Montesquieu's Pensées Diverses includes this observation:

Horace and Aristotle have told us of the virtues of their fathers and the vices of their own time, and authors down the centuries have done the same. If they were right, men would now be bears. […]

Apparently a major ursine transition in fact occurred at some point during the 1984-1985 academic year.

Monte Davis said,

February 27, 2011 @ 10:09 am

I've been anticipating a LL post on that rant, nearly perfect of its kind. You gotta savor that pre-emptive "nobody likes a grammar prig," especially when 90% of the citations have nothing to do with grammar.

The commenters blame TV, the educational system, the Internet, Obama, the Sixties, political correctness, and on and on. What a happy sandbox in which to model the culture wars!

But what do I know? I've been hibernating all winter.

-Smokey

Scott Y said,

February 27, 2011 @ 10:16 am

Yep.

chris said,

February 27, 2011 @ 10:44 am

What's the quack-talking he mentions? I can't find anything about it.

Marek said,

February 27, 2011 @ 10:56 am

I adore this sentence: "linguistic rabble has stormed the grammar palace". It's just so wonderful that you cannot actually tell whether he's being coy or serious.

Matt McIrvin said,

February 27, 2011 @ 11:18 am

I think there's something to it, but less specific: I do remember, in the late 1980s, coming across a collection of 1960s and early 1970s college newspapers and yearbooks in the library at William and Mary, and being shocked at how much better-written they were than the publications then being produced.

At the time, my hunch was that this was a consequence of increasing post-Sputnik emphasis on science and mathematics; science and math education had actually been getting more comprehensive, with English composition suffering in the process. (I was partly working from my father's observation that, by the time I finished high school, I had had almost all the mathematics education that he got by the time he graduated with a bachelor's degree in mathematics.)

It's possible that the campus publication teams had simply gotten less selective.

C Thornett said,

February 27, 2011 @ 11:48 am

I would guess that 'quack talking' refers to a quality of vocal delivery (pitch? timbre? tight throat muscles?) which the writer thinks resembles the quacking of a duck of unspecified breed, dislikes and expects his readers to recognise from that phrase. What the quality is I couldn't say, I'm afraid, but he wouldn't be the first to ascribe moral significance to vocal delivery.

Of course my judgements of spoken and written language are based purely on intrinsic aesthetic and communicative principles and should be heeded. [Harumph.]

sarang said,

February 27, 2011 @ 12:00 pm

cf. Philip Larkin, "Sexual intercourse began / in 1963"

Jean-Pierre Metereau said,

February 27, 2011 @ 12:03 pm

I've just finished grading a set of in-class essays from a sophomore English lit class, in which I asked them to explicate a poem and identify the Romantic elements. The students did a better job than I recall doing in my sophomore year in 1962. My esteemed professor must have been deploring the youth of that time as he decorated my essay with the adjectives "vague," "glib," and "facile."

"Le plus ca change…" (Sorry, francophones… I can't do cedillas on my computer.)

Marc B. Leavitt said,

February 27, 2011 @ 12:32 pm

M. Montesquieu joins a long list of commentators going back to the beginning of written records. In my humble opinion, intelligent, articulate and well-educated people have always communicated well. The type of nonsense quoted above reminds me of valley-speak. I think, among a multitude of factors, that socio-economic conditions must be considered before reaching a sweeping conclusion. It reminds me of the old codger who said, "In my day we walked to school through six feet of snow, and it was uphill there and back."

Harold said,

February 27, 2011 @ 12:50 pm

A conservative view, justifying prescription:

David Wiggins, Language the Great Conduit [of communication — compared by Locke to a canal] Excerpt:

http://www.abc.net.au/rn/linguafranca/stories/2006/1790249.htm

That language is changeable no doubt. It is a social object under constant renewal. The thing that is special about any particular language is not that it's timelessly ideal, but that as it stands at the point of speaking or writing, this language is, for the asking, his or her language – the indefinitely divisible birthright by possessing which one can draw at will upon a huge residue of that which has to now been thought, discovered, or felt. Language is that by which speakers and their inheritors can reach out beyond their own narrow world.

Here let us go back to John Locke and the Great Conduit. The conduit that he speaks of carries something wholesome to the public, and carries it by pipes. Consider then London's New River, not a river but a freshwater channel that Sir Hugh Myddleton, with the subvention of James I, brought all the way from a chalk outcrop in Hertfordshire to an open basin he had lined with stone slabs near Sadlers Wells in Islington, North London. The channel, ten foot wide and lined at various points with clay, wood or other materials, was dug along a contour, with a gentle fall of only 18 feet from start to finish along its meandering 40-mile route. At the southernmost end, the basin in Islington distributed fresh water to city subscribers by means of wooden pipes hollowed from elm trunks.

In conception and execution the New River was a triumph. But at every point in its entire length it was liable to leakage, to collapse and to contamination. On pain of its not conveying that which it was designed to convey, it stood in need of constant repair, both major and minor. Among major repairs some were effected by engineers of later times, who cut out troublesome sections by building aqueducts. They reduced the length of the river to 27 miles.

If language is at all like the Great Conduit, then the thing that language needs, or so the Lockean metaphor suggests, is unremitting maintenance, maintenance subsuming improvements. This is to say that the thing language needs at any time is for its norms of sense and syntax to be sustained. How though will they be sustained in the absence of prescription?

Exhortations and reminders about what means what in English say nothing either way for or against change. In the here and now, they simply sustain prescriptions for the here and now. They do however (to quote Samuel Johnson again) serve to 'regard what we cannot repel' and 'palliate what we cannot endure'. The effect of observance is to combat entropy, to make room for artistic and intellectual purposes that are pursued in language and to preserve and perpetuate meanings.

If each generation has backed its prescriptions with lamentation and protestation, that is what you would expect. It is the price we pay for holding onto something precious.

marie-lucie said,

February 27, 2011 @ 12:52 pm

jean-Pierre: in your computer's system there must be a list of languages – add French to the fonts and you should then see its little icon next to the ENG one and to choose one of the other as needed for what you are writing. For French you should be able to choose from France or Canada (the latter not too different from the English US keyboard).

Harold said,

February 27, 2011 @ 1:16 pm

On my computer with Word for Mac, you hold down the "alt" (option) key while typing c and you get ç — it only took me 5 years to figure this out!

Kir said,

February 27, 2011 @ 1:44 pm

Language Log produces some variant on this theme every couple of months. "People have always complained about 'kids these days', so obviously anyone complaining about this is wrong." I obviously read LL for the linguistics, not the logic.

I'll grant you that Whelton didn't make a strong argument himself, but I interpreted it more as a "this is when it happened to me" story, rather than a "this is when it happened". It seems fairly obvious that he ended up with a bad batch of intern applicants, and perhaps overgeneralized. He follows with an anecdote regarding daytime TV. This generalization doesn't make a strong argument, but it's certainly no weaker than yours.

[(myl) You've missed the point in this case. With respect to trends in the writing abilities of college graduates, presumably there's some complex but ascertainable fact of the matter, including issues of vagueness as well as other dimensions. The interesting thing to me is that Mr. Whelton makes not the slightest hint of an effort to discover what such facts might be — not even the cursory web search that turned up that 1977 article for me — but instead just lets his peeve flag fly.

If I were evaluating the results as a student essay, I'd give Whelton an A for rhetoric but an F for content. Nevertheless, I'm not tempted (without further evidence) to attribute his poor abilities as a researcher to his generation, to his profession (of political consultant and speechwriter), or to his political position (clearly well right of center).

As for the peeves of yesteryear, what follows from them is not that "kids today" rhetoric is always wrong, but rather that it should not be accepted without some evidence — of which Mr. Whelton provides none whatever.]

Cy said,

February 27, 2011 @ 2:01 pm

Come now Kir, you can troll better than that. That's not the logic and you know it. It's not some curmudgeon complaining about kids these days, it's some old curmudgeon with some crazy idea about the kids these days, using language as a way to paint them all the same color and then just as easily dismiss them. Quoted from the article:

"Did Vagueness begin as an antidote to the demands of political correctness in the classroom, a way of sidestepping the danger of speaking forbidden ideas? Does Vagueness offer an undereducated generation a technique for camouflaging a lack of knowledge?"

Kids are uneducated and I disagree with current mainstream politics – let's use how they talk funny to signify that they are the bad guys. These LL posts serve to remind us that people shouldn't get away with these ridiculous linguistic forensics and still have it count as an opinion – there's a science of language, and these people habitually disregard it.

Kir said,

February 27, 2011 @ 2:14 pm

Also, I'm surprised this didn't occur to me. Your so-called counter-example actually fits perfectly with Whelton's position.

Your "two experts in college writing instruction" explain that there has been a gradual decline in writing capability up to 1977 (the time of the interview). Does it not occur to you that perhaps university students who would intern as political speechwriters might have been holding themselves to higher standards than the rest of the student body, particularly for interviews?

[(myl) Whelton asserts that everything was great when he started interviewing interns (in 1978?), and continued to be great until 1985.]

You also missed the fact that he compared "squirrel woman"'s speech to a "high school junior", so I think he has a slightly different age group in mind when he refers to "idioms of childhood".

[(myl) Um, he complains that "And yet intern candidates were not hesitant or uncomfortable about speaking elementary school dialects in a college-level job interview." Last I heard, a high-school junior was eleven years past the start of elementary school, and at least five years past its end. It's true that Whelton is imprecise on this point, but that's not my fault. Rather, it's my point.]

None of this actually says that he's right and you're wrong. I actually believe Whelton is just ignorantly ranting about 'kids these days', but this LL entry provided no usable arguments against his opinion.

[(myl) We await with interest the "usable arguments" in your own contribution to the topic.]

Kir said,

February 27, 2011 @ 2:18 pm

Cy, I'm not trolling… I'm not even talking about the original article. I don't even disagree with your opinion of the original article. (I do find it odd that you think people shouldn't be allowed to have something count as 'an opinion' though… I'll assume that's not the word you meant)

The problem is that this LL post is just as bad as the article it's criticizing.

[(myl) As always, the LL public-relations department stands ready to refund double your subscription price in case of less than full satisfaction.]

bianca steele said,

February 27, 2011 @ 2:30 pm

The City Journal is a big bag of mostly grouchiness. I clicked on the link anyway, though. What I haven't been able to figure out even on a second reading is what is mean–specifically–by "kindergarten" modes of speech. Or what the writer thinks is missing. He also ignores the probability that as he hired more and more and more interns, others were doing the same, and that more and more and more college students were applying, lowering the average. Or that as internships were becoming more prevalent, other adults had begun influencing students as to whether or not they ought to apply for them. There are any number of possibilities that have nothing to do with real changes in kids' speech patterns, a fact of which the writer seems entirely unaware. He seems to believe he knows what the true reason is, so why doesn't he say this outright?

Colin said,

February 27, 2011 @ 2:34 pm

Let's also defend Squirrel Woman who, even via Whelton's condescending reconstruction, communicates both what happened with the squirrel and her own thoughts as it happened, using all the sound and visual resources at her disposal.

Steve T said,

February 27, 2011 @ 2:56 pm

Mandatory link to Taylor Mali poem supplied here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pKyIw9fs8T4

[(myl) Equally mandatory link to a critique of the cited rant.]

JR said,

February 27, 2011 @ 3:23 pm

A lot of the commenters there really dislike filler words, such as "like." Is it possible that, say, during Jane Austen's time, people did not use any filler words?

One commenter even suggests that this is a global trend: "This is not just an (American) English issue: the same thing is happening in the Netherlands and, I presume, in the rest of Europe. The specific phrases vary, but the overall pattern is the same: where in English one would say 'like', one says 'zeg maar' in Dutch."

mgh said,

February 27, 2011 @ 3:36 pm

given the growing number of college students, it is not unreasonable to expect that average college writing skills have decreased. But, as college becomes less and less for the elite, one would also expect that average overall writing skills have increased. as for the 1985 precipice, this makes sense as well, it being so difficult to compose while breakdancing.

Craig said,

February 27, 2011 @ 3:44 pm

The percentage of the American population achieving bachelor's degrees has steadily risen since WWII:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Educational_attainment_in_the_United_States

Professors are likely seeing students in college who, a generation ago, would have opted for business or trade schools, vocational training, or apprenticeships instead. I suspect that this might account for some of the supposed decline in student skills.

[(myl) This is one of many reasons that the writing skills of college students might have declined over the past half-century. But before spending too much time looking into causes, I'd like to start with some documentation of the decline that goes beyond anecdotes.]

Lance said,

February 27, 2011 @ 5:23 pm

I'm struck by Whelton's own Vagueness in his opening paragraph. What television program? Was the woman an actress playing a character? She didn't "say anything specific about her encounter", but was she trying to (was it an episode of "Public Speaking About Squirrels")?

But what's really amazing about his piece is the way he makes it clear in the last paragraph that, by 1991, the incoherence of American speech had descended to the point of absolute silence. It makes me wonder what it is we've all been doing for the last twenty years.

[(myl) Yes, the ending is extraordinary, veering past the bizarre into total nuttiness. ]

bianca steele said,

February 27, 2011 @ 5:45 pm

I might suppose the opposite of vagueness would be writing like the following, from the same issue of the magazine:

And the passage is indeed fine, and written by one of the paper's best writers, always with interesting things to say. Yet there are teachers living, through the vicinity of whose red pens, the vagueness, not to mention the validity, of "civilization . . . was founded . . . on coal," might not pass unscathed. (Hopefully that is correct comma usage.)

bianca steele said,

February 27, 2011 @ 5:56 pm

Anecdotally, the class entering Columbia College in the fall of 1984 was much less proficient than in earlier years. During orientation, first-year students were examined for placement into either remedial, ordinary, or advanced English composition. Supposedly, the same writing assignment was given that year as in previous years (if I recall correctly, it was a short parable involving the mishearing of the phrase "proper gander"), and students did much worse. (On the other hand, gossip is gossip, and I heard other things I'm now pretty sure were nonsense. Also, one of the people I heard this from was a classmate who was surprised at failing to be placed in the advanced course.)

Vireya said,

February 27, 2011 @ 6:01 pm

JR – a few years ago an Australian radio program I heard featured a linguist discussing the "new quotatives" such as "like" in various languages. These words are more than just fillers. There's a transcript of the program here: http://www.abc.net.au/rn/linguafranca/stories/2008/2451334.htm

[(myl) You could also take a look at this bibliography from the 2004 Stanford quotatives project.]

Janice Byer said,

February 27, 2011 @ 6:42 pm

"Knowing where you're going is mostly knowing where you've been," seems an apropos line from a Willy Nelson song. To know our common heritage is going down hill requires a bead on where its been unavailable to me.

Hermann Burchard said,

February 27, 2011 @ 6:58 pm

@Cy, Krl: Both troll and trawl are method of fishing, pulling a line or a net. Does anybody know how "troll" came to have this meaning? Earlier, it was kind of Scandinavian leprechaun, I think.

phosphorious said,

February 27, 2011 @ 7:00 pm

Speaking of vagueness. . . although I suspect Whelton is speaking of much more than this. . . we have a series of loaded questions, the lazy mans assertion:

"Is Vagueness simply an unexplainable descent into nonsense? Did Vagueness begin as an antidote to the demands of political correctness in the classroom, a way of sidestepping the danger of speaking forbidden ideas? Does Vagueness offer an undereducated generation a technique for camouflaging a lack of knowledge?"

Each of those questions involves a presupposition, which, were encouraging clarity the point of this article, would require more forceful expression.

Or junk.

army1987 said,

February 27, 2011 @ 8:07 pm

and the ability to speak at length without saying anything concrete at all is mastered fully only by mature politicians and their speechwriters

LOL!

bloix said,

February 27, 2011 @ 8:26 pm

Vagueness isn't really the subject of his complaint. What he doesn't like, I think, is the way that younger people don't narrate past eventsso much as perform them. "Like" in such cases is not a filler; it marks the transition from narration to performance. The words are often nearly contentless – "I was like, Whoa!" or "She was like, Hello-oh!" and the meaning is conveyed by body language, intonation, and context, as in any performance.

Which is all fine, except that you'd expect college students to be adept at code switching when talking to people a generation older who have the power to grant them something they claim to want (e.g., an internship).

lucia said,

February 27, 2011 @ 11:23 pm

bloix

Sure. But it's also possible that college students interested in internships on a project involving study of Velikovsky might be less interested in code switching than some applying for internships that might results in better employment prospects after the end of the internship.

Googling Clark Whelton suggests Velikovsky may have become an ongoing interest of his at the time.

http://www.velikovsky.info/Clark_Whelton

http://abob.libs.uga.edu/bobk/vwhelton.html

Nelson said,

February 27, 2011 @ 11:59 pm

bloix: "vagueness isn't really the subject of his complaint.."

"What I found ironic was his self-referential complaint of "Vagueness" in which he failed to find a correct word for what he meant. Phrases such as "like" and "no problem" are much clearer and easier to understand than an arbitrary labeling of speech patterns as "Vague" because Whelton happens to dislike them. Some of his points had merit, but you would expect Whelton to think about what to call his peeves are in an complaint supposedly against vague thinking.

Laplacedemon said,

February 28, 2011 @ 12:34 am

Ah, so the English language became infantilized in 1984? What a doubleplusungood occurrence.

JR said,

February 28, 2011 @ 2:24 am

Thanks, Vireya, for that link.

But she does sorta agree with Welton that these days people are reluctanct to say what they really mean.

And if "like" is a quotative, fine. But Welton and the commenters seemed to be talking about more than that. I.e., things like "whatever," or "umh" or Spanish "este" or Dutch "nou." They seem to be saying that these days people are filling their speech with a bunch of crap, as if it were something new. So, I ask again, is it new?

Cy said,

February 28, 2011 @ 2:26 am

@Hermann Burchard: visiting etymology online (http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?search=troll&searchmode=none), it seems like the pertinent use is from troll(v), "to cruise in search of sexual encounters," (slang) which itself is probably from the "trawl" you mention, not the thing under the bridge. That's completely, anecdotally my opinion though, and how I parse the semantics, it's probably unrelated to the etymology. I know people like o think of it as the leprechaun now, though – e.g. "don't feed the trolls."

@Kir: I suppose one can have an opinion, unsupported by facts, about things like whether muffins taste good, or something. But again, this is an area where there could possibly be pertinent facts. Qualified opinions are allowed, in these domains, but they must still deal with those qualifications, not simply be couched in anecdotes and knee-jerk reactions. From your response it sounds as though you might entertain all opinions as being equally valid, which, since we're being charitable about misunderstandings, I'll assume that's not the word you meant.

Stephen Nicholson said,

February 28, 2011 @ 2:56 am

I find the label of vagueness misleading, as many of his complaints don't have anything to do with vagueness at all. The use of "like" is not vague, nor is the use of "no problem". Frankly, "no problem" as a substitute for "you're welcome" seems like the opposite of vagueness. I'm not saying people can't dislike it, or that there is nothing objectionable about it, but it isn't vague.

I can't help but wonder if there is another explanation for the interviewee's answer sounding like a question. Sometimes, when people don't understand why a question is being asked, or if they suspect that the question is some kind of trap, the answer will have the same "interrogative rise" Whelton complains about. If Whelton asked "where did you go school" in a manner that could be reasonably interpreted as condescending, that could elicit the response he got. Given that he claims to have noticed a drop in applicant quality in 1985 and he says this happened in 1987, that's a possibility.

But no matter what, I'd have to say that the "interrogative rise" isn't vague. Nor is body language in general.

maidhc said,

February 28, 2011 @ 4:19 am

What happened to the field of political speechwriting in 1985 that it suddenly stopped attracting the best student writers? Obviously the ever-increasing mediocrity of political discourse is the root of the problem.

maidhc said,

February 28, 2011 @ 4:26 am

"Trawling" is a kind of ocean fishing in which a big net is dragged through the water.

"Trolling" is a method of fishing for trout in which a lure is pulled slowly through the water.

I wouldn't be surprised if they came from the same root.

It seems to me that the internet usage of trolling comes from the trout-fishing method, and the noun "troll" is a back-formation.

The activities of Scandinavian mythological creatures are reported to be quite unlike the internet activities in question.

[(myl) The OED says that

The earliest citations are from the 17th century:

1606 S. Gardiner Bk. Angling 28 Consider how God by his Preachers trowleth for thee.

1653 T. Barker Art of Angling 9 The manner of his Trouling was, with a Hazell Rod.

1675 J. Crowne Countrey Wit v. 73 Here have I been Angling and Trowling for my Father-in-law, and have had him at my Hook all day.

1682 R. Nobbes Compl. Troller xi. 56 In some places they Troll without any Pole or any playing of the Bait, as I have seen them throw a Line out of a boat, and so let it draw after them as they Row.

This is not much later than the earliest citations for trawl "To fish with a net the edge of which is dragged along the bottom of the sea to catch the fish living there",

1561 R. Eden tr. M. Cortes Arte Nauigation Pref. iv b, Certayne Fyshermen that go a trawlyng for fyshe in catches or mongers.

1630 Order in R. Griffiths Ess. Jurisdict. Thames (1746) 77 No Trawler that‥doth use to Trawl to take Soal, Chates, Plaice or Thorn-back.

]

army1987 said,

February 28, 2011 @ 5:58 am

@JR:

Something I've noticed in people fluent in both English and Italian is that many of them tend to use the same kind of filler words in both languages: those who often say cioè in Italian often say I mean in English, those who often say tipo in Italian (including myself) often say like in English, ditto with allora and so etc.

Matt McIrvin said,

February 28, 2011 @ 8:14 am

I wonder if some of the interns he complains about just happened to be from Southern California, where an end-of-sentence rise on some declarative statements is common. (Language Log has, I think, discussed this in detail before: if I recall correctly, peevers tend to interpret the rise as indicating uncertainty or deference, but in actual use it indicates the opposite.)

In the 1980s, there was also a wave of "Valley Girl" jokes that established in popular culture the idea that this feature of SoCal accents was a sign of vapid, contentless chatter, and that might have contributed to his impression.

Rodger C said,

February 28, 2011 @ 8:23 am

@Bianca Steele: "[A] short parable involving the mishearing of the phrase 'proper gander'" would confuse anyone who spoke a rhotic dialect. Non-rhotic American dialects are in retreat. Could this have something to do with the phenomenon you mention?

Rodger C said,

February 28, 2011 @ 8:27 am

Not to mention that American youth are increasingly unfamiliar with domestic fowl.

Matt McIrvin said,

February 28, 2011 @ 8:31 am

Past discussions here, here, here, here.

bianca steele said,

February 28, 2011 @ 8:42 am

Rodger C:

Googling turns up a story by James Thurber that is almost certainly the one we were asked to comment on.

Occasionally I have found myself answering questions with a final rise when I know there will be another question. For example, after "street name?" I expect to be immediately asked "town?" and after that, "zip code?" (I suppose there are even cultures where "street name?" would be asked without a final rise.)

bianca steele said,

February 28, 2011 @ 8:46 am

Also @ Matt McIrvin: Among women a little younger than me, from different parts of the country, I've been surprised to hear what I've always thought of as a Northeast Philadelphia accent.

Ray Dillinger said,

February 28, 2011 @ 12:43 pm

Some on this list have referred to the use of "like" as a filler word.

I don't think that is what's happening here.

I think that "like" or "is like" is settling into a definite grammatical role at least as precise as "said", (at least in the affected dialects) but signifying paraphrase or internal monologue rather than direct quotation.

When squirrel woman says "and I was like, what are you doing here?" she's reporting internal monologue. The phrase "I was like" is analogous in her dialect to "I said" as a report of actual speech.

Hermann Burchard said,

February 28, 2011 @ 1:35 pm

MYL, Cy, maidhc: Thanks for the explanations on troll and trawl. As an immigrant, I thought "troll" was a mistake when I first heard in the meaning of trawl. The antiquity of spelling variants is surprising, MYL, but does not necessarily indicate pronunciations. But this gets too far afield to pursue here on this LL blog, which appears to reflect ongoing culture wars, "vaguely" apparent from yall's comments (hope you forgive my topolect).

J.W. Brewer said,

February 28, 2011 @ 4:02 pm

Excellent catch by lucia on the Whelton/Velikovsky nexus. Perhaps historical linguistics needs a Velikovsky-like figure to shake up the consensus with ingenious tales of primordial catastrophe?

[(myl) Bring back "wrathful dispersion theory"!]

Hermann Burchard said,

February 28, 2011 @ 5:27 pm

@lucia, J.W. Brewer: BTW, despite Clark Whelton, catastrophism is alive and well although unfunded and growing more quiet with age, but also gaining more acceptance from main-line geology, as can be seen on Wikipedia's Siva Crater page. Shown there, is a magnificent graphic by Chatterjee et al of the 500 km Siva crater, image based on gravity anomalies.

This impact split India from Africa and probably was almost simultaneous with the better known, but much smaller, Chicxulub crater in Yucatan, which is most often blamed for the end-Cretacious extiinction event.

To quote from one reference cited by lucia: "Contrary to Mr. Whelton's implication, to debunk Velikovsky's catastrophes, as I did, is not to deny catastrophism in general, just Velikovsky's specific catastrophes."

Jenny said,

March 1, 2011 @ 3:16 pm

Matt McIrvin, I like your thought about the interns possibly being from Southern California. I don't know if you live here, but I do, and "Valley" sounds to me like a collection of regional dialects. My friend from the actual Valley told me she used to be able to distinguish six dialects in that area. Valley Girls do have a reputation as airheads (though they aren't more air-headed than anyone else).

Monte Davis said,

March 2, 2011 @ 8:55 am

"This impact split India from Africa…"

Ummm… your geomorphological credibility appears to have fallen into a subduction trench there.

Peggy said,

March 2, 2011 @ 12:19 pm

Jenny, the first time I heard "and I was like, oh my GOD, and she was like, and I…" blathering was Glasgow (Scotland) 1986. I don't think we had valley girls on TV in the UK then, but I'm not sure. Perhaps he had Glaswegian speech writers?

Hermann Burchard said,

March 2, 2011 @ 7:48 pm

@Monte Davis, "This impact split India from Africa…":

Could you be more specific please? Which part of the sentence is hard on your credulity? This is a well-known theory (I believe due to Professor Chatterjee, Lubbock TX). Accordingly, the impact created the Carlsberg Ridge spreading center (divergent plate boundary) which is responsible for driving the Indian plate away from the African. Sure, mainline geologists are slow to accept the idea that (large) meteorite impacts had a major influence on plate tectonic, but this is a very conservative science, so they need more time (as did Han Solo on the Forest Moon). Eventually this now heterodox causal relationship will become orthodox geology. Possibly, you have heard it here first. I didn't mean to use up the LL bandwidth with this but your objection left me no choice, sorry MYL.

Monte Davis said,

March 3, 2011 @ 2:15 pm

Chatterjee believes his claimed impact at ~65MA displaced the spreading center to the Carslberg Ridge, and may have accelerated the northward movement of India.

But (as he knows) India was already at least 1500 km from Africa by then; it hadn’t been adjacent to Africa since the middle Jurassic (150 MA), and continued on much the same divergent, Asia-bound vector for a long time before and after 65MA. So the claim that the impact “split India from Africa” is yours, not Chatterjee's. Don't hide your creativity behind bogus appeals to authority — be proud!

Hermann Burchard said,

March 3, 2011 @ 6:40 pm

Am unable to verify what you write about Jurassic age of India-Africa split.

Certainly had no intent of hiding my own ideas under false appeals to authority. Perhaps I learnt of Carlsberg ridge and Shiva impact form another source? Do seem to recall a paper by Alt, Hyndman, Sears on such matters. It's been one of my interests for a long time.

Chatterjee is a bit cautious knowing how odious ET impact effects are to mainstream geologists. His paper on the Shiva was never published, I believe. The reality of the impact itself was denied until recently by geologists.

I did correspond with Chatterjee about Deccan volcanism, which he concedes is older than Shiva impact. The coincidence is unlikely. But here is an example where I know that I differ from him. The main Deccan LIP is a result of the impact penetrating the crust and opening up a cavity initially 1/10 of crater diameter, or 50 km, deep before collapsing, enough to cause the massive magmatic outpouring the result of which is the Deccan.

Hermann Burchard said,

March 3, 2011 @ 7:27 pm

Alt, Hyndman, Sears (1988) mention a "narrow strip of Cretacious sea floor between the Carlsberg ridge and mainland India." But they also state the "nearly semi-circular Amirante ridge [is] Cretacious sea floor enclosing an expanse of Paleocene basalt." And they do show a stretch of ocean between the Amirante arc and Africa, which I suppose is the 1500 km spread you mention.

From this it appears that I was simply wrong in stating the Shiva impact split India from Africa: Instead, it split India from the Amirante arc which is now about 1000 km East of the African coast (not 1500 km).

"Restoring the Amirante Ridge to the position.. before spreading began at the Carlsberg Ridge brings a semicircle approximately 600 km in diameter against the Indian mainland.." Thus the Western half of the crater wall is now the Seychelles, aka Amirante Arc, 3000 km from India. This is where the split occurred, not at the African coast. They credit papers from 1968 and 1977.

@myl: Apologies for my faulty recollection, and for wasting electrons.

Peter G. Howland said,

March 4, 2011 @ 3:24 am

Wow! From claims of vague-speak by intern applicants to debates about impact crater influences on plate tectonics! Who could ask for more? Thanks for letting these comments stand, myl…it's this kind of stuff that keeps me up all *swearword* night reading LL, dammit!

My thoughts on Standard English « Gordon P. Hemsley said,

March 6, 2011 @ 6:21 pm

[…] What Happens in Vagueness Stays in Vagueness and a follow-up to Language Log's rebuttal, The curious specificity of speechwriters. But it quickly evolved into something that begins to express my feelings about the whole issue of […]

Why Sentence Diagramming Does Not Make You Superior, An Argument In Support of Those Kids Today | Alas, a Blog said,

March 29, 2011 @ 8:18 pm

[…] from the internet, provided a link to a language log article articulating yet more opinions on when the Doom of Grammar fell upon […]

Hermann Burchard said,

April 16, 2011 @ 12:08 am

To "troll" vs "trawl" (which I still prefer to think of as being semantically indistinguishable and "troll" a spelling error):

The TELEGRAPH (online, London), repoerts, byline Mark Hughes, Crime Correspondent 9:15PM BST 15 Apr 2011: The number of victims who had their phones hacked by the News of the World may be “substantially higher” the Metropolitan Police has admitted after it began trawling through nearly 10,000 records of private investigator Glenn Mulcaire.

(My emphasis.)

The TELEGRAPH uses "trawl" where commenters on this blog likely would have put "troll."