How Mubarak was told to go, in many languages

« previous post | next post »

In the New York Times Week in Review this weekend, I have a piece looking at the clever linguistic strategies that Egyptian protesters used to tell President Hosni Mubarak that it was time to go. (There's also a nice slideshow accompanying the article.) Language Log readers will already know about the appearance of "Game Over" in the Cairo protests, as well as the use of Chinese to get the message across, but there were many other creative variations on that theme.

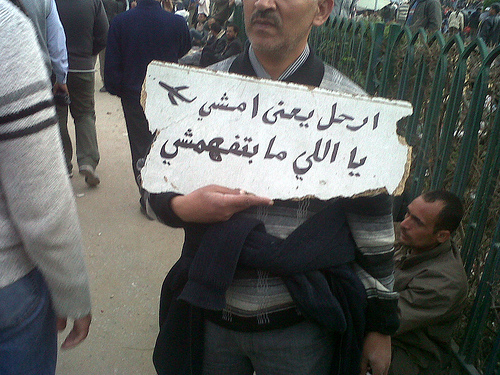

I learned from Noha Radwan, who spent a week with the protesters at Tahrir Square, that a popular rhyming chant translated the word irhal 'go' from Modern Standard Arabic into the colloquial Egyptian imshi (which I gloss as 'beat it' in the Week in Review article):

irhal ya'ni imshi (irhal means imshi)

ya illi mabtafhimshi (in case you don't understand me)

Gregory Starrett first pointed me to this couplet, as it appeared on a protest sign captured on Flickr (the departing plane is a nice touch):

He added:

Mubarak has sometimes been criticized for not being able to maintain high standard speech in public addresses and interviews, lapsing after a while into local pronunciations and idioms, the implication being that he's uncultured. So this is an joking attempt to translate the more formal "irhal" into informal speech that he might comprehend better.

From Walter Armbrust, who is spending a sabbatical year in Cairo (and what a year to be there), I learned of another fascinating sign using hieroglyphs to help convey a message to "the pharaoh" (Mubarak):

i-h-r-l [Arabic letters under their hieroglyphic equivalents]

bil-hayro glif yimkin tifham ya fi'un

in hieroglyphs maybe the pharaoh will understand

(Unfortunately I haven't seen a photo of this one yet. Update: see below.)

As for foreign languages, this photo (taken by Rebecca Mohey and sent to me by Susan Richards-Benson) shows stones arranged to spell commands of departure in five languages — Arabic إرحل (irhal), Spanish fuera, French dégage, English go out, and German raus:

(For more on English-language wordplay from the Egyptian protests, see my Word Routes column on the Visual Thesaurus. And for those interested in the parallels with Indonesian wordplay at the end of the Soeharto era, see my paper, "The New Dis-Order: Parodic Plésétan and the 'Slipping' of the Soeharto Regime," Antara Kita: Bulletin of the Indonesian Studies Committee of the Association for Asian Studies, July 1998, 54:4-9).

Update: Teresa G (in the comments below) has located a photo of the sign with hieroglyphs here.

Duncan said,

February 13, 2011 @ 5:38 am

My command of Egyptian Arabic is by no means perfect but I would have thought that the second line simply meant "You who don't understand me", with يا being a vocative particle. What I found more interesting about that sign was that in three cases (اللي، امشي، and بتفهمشي) the final letter ي was written with its two dots underneath it, whereas in Egypt they are almost always omitted.

djbcjk said,

February 13, 2011 @ 6:35 am

Imshi has become a pice of Australian slang, brought back by the soldiers from Egypt in World War I. It's of course now getting pretty obsolete. It was the name of the soldiers' magazine on the troopship "Karoa" and features on an unofficial medal in the Australian War Memorial collection, issued by the Arts and Crafts Association of Sydney to commemorate the Australian landings at Gallipoli in 1915. Versions were produced in bronze, silver and gold. The War Memorial comments: "The medalet's obverse depicts an attacking Australian solder and the words 'IMSHI YALLA'. This phrase, an indecorous way of saying 'Go away!', was learned by Australian troops in the streets of Cairo during the early stages of the First World War."

Victoria F-C said,

February 13, 2011 @ 1:22 pm

Just as a note..there were protests in support of the Egyptian revolution here in Frankfurt. As well as Arabic (which sadly I could not understand) there were also German chants.

"Eins zwei drei, Mubarak ist vorbei!" (one to three, Mubarak is over!)

As well as signs in English, German and Arabic including "Hillary! Man up or shut up!", "Mubarak raus" and "Menschenrechte" A few photos here: http://frankfurtmainly.blogspot.com/2011/02/eins-zwei-drei-mubarak-ist-vorbei.html

Mr Fnortner said,

February 13, 2011 @ 1:39 pm

Slightly off topic, yet I have seen several handmade signs held by participants on which the lettering was almost perfect, as in the one shown above. It seems unlikely that the piece of board above was mechanically printed in a local shop, so I wonder about the amount of rigor involved in teaching young

Egyptian students to write. I have also noticed Chinese signs with this level of (presumably) handmade quality. Is this level of perfection typical among writers in certain countries?

GeorgeW said,

February 13, 2011 @ 4:31 pm

@Duncan: "I would have thought that the second line simply meant "You who don't understand me"

Close, but not quite. There is no 'me' direct object. 'You who doesn't understand' would be closer. The 'ya' suffix in the second line is there to rhyme with 'imshi.' It is poetry, not prose, so some liberty was taken with the grammar.

Arnold Zwicky said,

February 13, 2011 @ 11:45 pm

This is a fantastic piece of writing about language in a public forum. Yes, Ben is a friend of mine, but, stiil, I can't imagine writing anything like this. I was going to post about this on my blog, but here's a better place to say how much I admire it.

Jay Sekora said,

February 14, 2011 @ 12:26 am

@Mr Fnortner: I wonder if some of it might be that signmaking by hand is still much more common in Egypt and China than in North America and Western Europe. If you look at American photos from the first half of the last century (or from the 19th century, for that matter) you see very carefully hand-painted signs, many of which (e.g., newspaper headlines tacked up in large letters outside a newspaper) were fairly ephemeral. Nowadays we in the industrialized West don’t tend to get much practice in careful hand-lettering, so we’re pretty bad at it as a rule. But in China and presumably Egypt, a lot of public signs are still drawn (I was going to write “lettered”, but that doesn’t fit for Chinese) by hand, and the shopkeeper who makes a neat, even, clear sign announcing this week’s sales is also going to be able to make a neat, even, clear protest sign.

(I think China and the Arab world also tend to pay a lot more attention to calligraphy as an art form and a skill that children are expected to learn, and that’s certainly also part of it. But I suspect that that itself is in part because it’s still a practical skill in daily life.)

Ellis said,

February 14, 2011 @ 3:22 am

Noted in the protests in Italy yesterday: a picture of Berlusconi being kicked by the boot of Italy with the wonderful caption MO'SBARAK, or NOW CLEAR OFF.

[(myl) Beautiful!

(From this video.)

I guess this involves a form of sbaracare "to disembark", preceded by the regional mo "now". In standard spelling it would be "Mo' sbarca", right? Is the final '-a' in "sbarca" one of the final vowels that's subject to apocope? ]

GeorgeW said,

February 14, 2011 @ 6:04 am

Jay Sekora: I have never noticed hand-made signs being common in Egypt or the Middle East. But, yes, calligraphy is an art form in Arab culture.

Fiorentino97 said,

February 14, 2011 @ 10:24 am

GeorgeW's analysis is right on. I would add a minor qualification, however: while the "yā'" on "mabitifhamshi" is likely added for orthographical symmetry with "imshi," it really does reflect the underlying pronunciation and doesn't necessarily represent a "liberty" taken with the grammar. Egyptian Arabic (or perhaps I should say Cairene, with which I am most familiar) inserts an epenthetic helping vowel after a two-consonant cluster, even when it occurs at the end of a phrase. (It may be optional at phrase end; it is obligatory when the cluster is followed by a third consonant.) As the spelling of the colloquial isn't standardized, this helping vowel can legitimately be written as a "yā'".

Teresa G said,

February 14, 2011 @ 12:04 pm

I was very intrigued by your description of the sign in hieroglyphics and wanted to see it myself. It was surprisingly difficult to find by googling in English, and I had to use Google translate instead to search in Arabic, which finally yielded success (I think). Is this it?

http://mrmoufid.blogspot.com/2011/02/blog-post_10.html

The direct link to the image:

http://tinyurl.com/489aq2t

[(bgz) Thanks! Added as an update above.]

Nijma said,

February 14, 2011 @ 6:09 pm

@ Mr Fnortner handmade signs held by participants on which the lettering was almost perfect

An Egyptian once wrote my name in calligraphy for me over a finjon of Turkish coffee, but I have no idea how common that skill is. I have seen several alphabet charts like this one, but when I have seen Arabs write with a pen, they don't write exactly like that, for instance seen and sheen are written as long lines, two dots become a short line, and the letters are on different levels rather than in line with each other.

Since historically Islam has frowned on images, Koranic verses are popular as decoration. Every home I was in had a "sura Koran" over the door as you go outside, a verse of the Koran in calligraphy with decorative borders. "Sura" is the same word they use for photograph, I suppose "picture". I once saw such a sura Koran that had been incorporated into the plaster of a building in a remote area. When the building was renovated, the calligraphy was carefully preserved high in the new wall. Of course Egypt may be different – I have been told Jordan is very religious compared to other countries in the Middle East, for instance, you can see people stop to pray during the day in their shops or street stalls, which I understand you don't see in other countries.

GeorgeW said,

February 14, 2011 @ 8:19 pm

Nijma: One little nit to pick. You say, " "Sura" is the same word they use for photograph."

These are not the same. The first segment in sura 'chapter in the Qur'an' is a siin. In the word for 'picture' the first segment is saad, similar but pharyngealized. To our English hearing ears, they often sound the same and are easily confused.

(Sorry, I can't get IPA or Arabic script into this form)

Mr Fnortner said,

February 16, 2011 @ 10:54 pm

Jay Sekora and Nijma, Thank you for the stories and information. In the US, good penmanship is a lost art.

Nijma said,

February 19, 2011 @ 3:44 pm

@ Mr Fortner, if you are interested in more about Arabic calligraphy, see this comment.

Nijma said,

February 19, 2011 @ 3:45 pm

@GeorgeW An Arabic professor has just confirmed for me what you say: sura=photograph صورة , sura=chapter of Koran سورة; he calls the protective Quranic verse over the door سورة قرآنية. And for getting Arabic or IPA script onto a form, there's nothing like cutting and pasting from websites like Google Translate or the Wikipedia IPA article.