Roman-letter Mandarin pronoun of indeterminate gender

« previous post | next post »

From B JS:

Some interesting uses of the Roman letter third person pronoun “TA” to sidestep genders associated with the characters tā 他 ("he") and tā 她 ("she"); it seems useful enough to perhaps become a permanent fixture in the language, in contrast to more faddish-seeming things like “duang” (see here and here). I kind of wish you could do this in English.

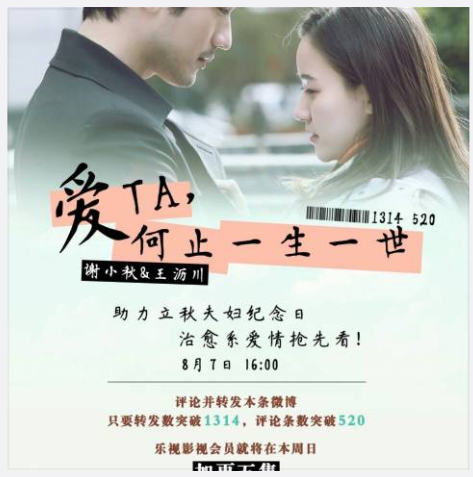

ài TA, hézhǐ yīshēng yīshì 爱TA,何止一生一世

("to love him / her, it will be for more than a lifetime")

Here's another example, with "TA" ("he / she") occurring three times:

Nǐ yǒu méiyǒu àiguò yīgè yáoyuǎn de rén, TA shì nǐ de yǒngqì hé lìliàng, TA yǒngyuǎn niánqīng měihǎo! guāngmáng wànzhàng! lái shuō chū TA de míngzì

你有没有爱过一个遥远的人, TA是你的勇气和力量, TA永远年轻美好! 光芒万丈! 来说出TA的名字.

"Have you ever loved someone who is far away? He/she is your courage and your strength; he/she is always young and handsome / beautiful! Rays of light [extending] thousands of feet! Come speak his / her name."

We needn't go into the other characters that also function as the third person pronoun — 它 (neuter), 牠 (with "bovine" radical [for animals]), and 祂 (with "spirit" radical [for deities]; all of these are pronounced tā) — because we've already discussed them, and indeed "TA", extensively in this post:

"The degendering of the third person pronoun in Mandarin" (12/12/13)

More evidence that the Roman alphabet has become a part of the Chinese writing system.

[Thanks to Fangyi Cheng and Yixue Yang]

leoboiko said,

August 9, 2016 @ 9:11 am

Japanese has no widespread word to denote "siblings" in a completely neutral, non-gendered way. There are 兄弟 kyō-dai, elder brother – younger brother = “brothers”; and 姉妹 shi-mai, elder sister – younger sister = “sisters”. There's a 兄弟姉妹 kyōdaishimai but that's a mouthful and, I think, mostly a technical term. In general usage, when one needs to talk about “siblings”, kyōdai is pressed into service, as in some European languages.

I was reading the Japanese comic book Hunter × Hunter and there's a character, Alluka, who has strange, dangerous powers, and is ostracized by their family. Alluka's appearance is that of an androgynous child; and their cruel relatives gender them as male. However, their brother Killua is protective of Alluka, and claims to understand them like no one else. Killua genders them as female, probably respecting Alluka's self-identification.

I know, this is Languagelog, not Transgender-Issues-In-Japanese-Comics-Log. What I found relevant to this discussion is how Killua's choice of gendering is written down. Japanese has no grammatical gender. Killua refers to himself and Alluka as kyōdai; but this is written as a gloss over the characters 兄妹, “elder brother – younger sister”, specifically selecting the “siblings” sense of the word (well, something even more specific than “siblings”). Notice that this is an irregular kanji reading; the regular compound reading of 妹 “younger sister” is mai, but *kyōmai isn't a Japanese word.

In-story, we know Killua is pronouncing the sounds kyōdai, because that's what's written in the furigana gloss. But we also know that he means “sister”, because that's the sense of the kanji. This is one of a number of Japanese techniques which employ the kanji-gloss system for literary effect, using the gloss to convey the sound and kanji to convey the meaning.

david said,

August 9, 2016 @ 1:36 pm

IIRC there is a monument at West Lake in Hang Zhou commemorating the gendering of Ta to facilitate translation of Western literature.

flow said,

August 9, 2016 @ 2:01 pm

In German, there is 'Geschwister' (siblings), a collective noun apparently derived from 'Schwester' (sister) (akin to 'Gewitter' (thunderstorm) from 'Wetter' (weather), 'Gebirge' (mountain range) from 'Berg' (mountain) and others). It is a rare case where (a derivative of) the female form is used collectively for both (all / two / a plural number of) genders. I really had to get used to that as a kid, because that word is so close to 'Schwester' it sort of seems unlikely it should apply to brothers as well.

David Marjanović said,

August 9, 2016 @ 2:46 pm

^ Looks like I have a higher tolerance for this kind of thing. I sort of… didn't notice till I read about it. After all, the counterpart Gebrüder, which strictly means "brothers", is downright literary these days.

Bathrobe said,

August 9, 2016 @ 3:36 pm

Didn't 他 only became gendered (that is, differentiated into 他, 她, 它 etc.) in written Chinese under the influence of English? Writing it TA would mean coming full circle.

Bathrobe said,

August 9, 2016 @ 3:37 pm

Oops, I see that has been covered at the earlier post (linked to in the article).

Bob Ladd said,

August 9, 2016 @ 3:42 pm

@ David Marjanović: Downright literary except in company names, where Gebr. is equivalent to English Bros. or Italian F.lli, and still current, as far as I can see from a quick web search.

LN said,

August 9, 2016 @ 3:51 pm

In manga, written language frequently gets overladen with signifiers that can't possibly be preserved in spoken language. Julia's

LN said,

August 9, 2016 @ 4:21 pm

(Continued from above; I accidentally hit "post" while doing battle with my phone's autocorrect. Sorry!)

@Leiboiko:

I've noticed that in manga, written language is frequently laden with signifiers that can't possibly be preserved in spoken language. In many cases, furigana are the mechanism of oversignification. Killua's use of 兄妹/きょうだい is just one such example; in the same manga, Hisoka's attack 伸縮自在の愛 is glossed as バンジーガム in the furigana. But there are other ways to smuggle in unvocalizable meaning—consider, for instance, Hisoka's habit of ending his sentences with card suit symbols.

leoboiko said,

August 9, 2016 @ 8:27 pm

Definitely so, but that technique isn't by any means exclusive to manga (though it's definitely ubiquitous in manga and games). At least since the Man'yōshū (the first poetical anthology) Japanese written works have been experimenting with layers of meaning and sound in all possible combinations and juxtapositions. The creative gloss technique was a staple of popular literature during the Edo period; see Ariga, The Playful Gloss, for examples. I find it in technical texts, too; for example, 国文学 glossed as National Literature in katakana (ナショナル・ リテラチュア) in an academic textbook. Advertising and song lyrics are also good places to spot playful glosses.

cliff arroyo said,

August 10, 2016 @ 3:09 am

Has anyone commented on the incredible sexism of interpreting the character with the person radical as male?

Wouldn't it have been much more logical to create a male radical for 'he' female radical for 'she' and leave the old person radical as an epicene?

Rachel said,

August 10, 2016 @ 6:36 am

Nicole Darcy has a song that I often find myself thinking about that makes exactly that point, cliff arroyo.

Rodger C said,

August 10, 2016 @ 6:44 am

@Bathrobe: I learned my first Mandarin (which remains most of my Mandarin) from already-old library books (interwar period), and they treated the gendering of ta as not only a recent Western-inspired innovation, but one that would or should die.

John Roth said,

August 10, 2016 @ 7:06 am

On the gender-neutral pronoun front, I've often thought that the issue is simply that there isn't an agreement among the people who are concerned. If everyone involved got into the same room and hashed it out, and then the survivors left to browbeat their editors and publishers into allowing it, this issue might get settled.

Meanwhile, I suppose there are worse solutions than repurposing a plural pronoun as singular.

Bathrobe said,

August 10, 2016 @ 7:52 am

one that would or should die

Another innovation that I wish would die is the distinction between 的, 得, and 地 (all de). Even Chinese get confused. And why is 真的 (zhen de) always written like that? Surely in an adverbial sense it should be written 真地 — although it never is.

Victor Mair said,

August 10, 2016 @ 9:21 am

Here's the video from which the second image (screenshot) is taken. The weird, wild speech of the actors is speeded up to a degree that makes it very challenging to follow, especially since they are fond of throwing in words from other languages. Note that the subtitles use a conspicuous amount of Romanization.

Dan Lufkin said,

August 10, 2016 @ 10:09 am

FWIW, in Swedish the generic word for "person" (människa) is always feminine (but grammatically common gender).

Chas Belov said,

August 11, 2016 @ 2:54 am

I don't get why they felt they had to keep the distinction when translating Western literature, if Chinese literature didn't require the distinction any more than Chinese required a plural distinction in most cases.

flow said,

August 11, 2016 @ 6:23 am

@Chas Belov—that may be explained with "translational fidelity", where a translator (out of lack of skill or by conscious choice) sticks close to the original, to the point where particular wordings shine through, as it were. When you translate English, Swedish or German to Chinese in this way, you'll get unnaturally high contents of 3rd person pronouns (and also, for some texts, a vexing proliferation of 人們 for E 'people', G 'die Menschen', 'die Leute', 'man' and so on). It is this unnatural, non-native way of speaking that develops a crave for differentiating graphically what is undifferentiated phonologically. How else could you translate, say, "he wanted to go but she didn't"?

liuyao said,

August 11, 2016 @ 10:25 am

@Bathrobe

I heard that elementary schools in China no longer enforce the distinction. You can write all de as 的

Avinor said,

August 11, 2016 @ 10:31 am

Dan Lufkin:

It's feminine when used in the sense of man(kind) or abstractly. For a specific person, you use the normal animate personal pronouns 'han' or 'hon' according to gender. If not wanting to specify gender, I would use the inanimate common-gender 'den'. Trendy lefty types use the invented 'hen'.

Greg said,

August 11, 2016 @ 10:48 am

@cliff arroyo: It's a poor excuse, but the person radical is just 2 strokes, and the character for "man" is 6! I wonder if 他 has always been interpreted as necessarily male. Does 她 date back just as far? This is just a guess, but I wonder if TA/他 originated as gender neutral since it seems there is no distinction in spoken language. The flexibility of the writing system then allowed for male/female disambiguation, and so 她 was born. Is it the case now that 他 is ever used as gender neutral? There doesn't seem to be a standard character that combines 男 and 也, so I do see an argument for three characters: neutral/ambiguous, male, and female.

Chas Belov said,

August 11, 2016 @ 11:39 am

@flow "How else could you translate, say, "he wanted to go but she didn't"?"

How do you normally express that in 他-only Chinese?

Victor Mair said,

August 11, 2016 @ 12:08 pm

@Greg

nán 男 has 7 strokes, not 6

I have to run for a train, so I can't answer your questions about the history of 他 and 她. I'm hoping that someone else will do that. Otherwise, this may have to wait until late tonight.

flow said,

August 11, 2016 @ 1:49 pm

@Chas Belov—see, that's the thing, I hardly can. Of course I *can* give you, say, 他雖然想去,她卻不要, but I'd rather prefer not to put it that way. The thing is, without knowing who 'he' and 'she' are, what their names are or what kind of relationship they have, it is hard to replace the generic 3rd person pronoun—ta—with something meaningful that allows to me to evade that infelicitous 'ta¹ …, ta²…' pattern.

Maybe there is some way of putting it in colloquial Mandarin, using some device similar to that US usage, 'you guys' (as in, asking your mother on the phone, "how're you guys doing"). It often occurs to me that when I watch German-dubbed episodes of Voyager or Enterprise that the translations use "Sie" (polite 2nd Person singular and plural, goes with plural verb, 'you (sir)') and "sie" (3rd person plural) in confusing ways a German would avoid. These arise from phrases that use "you" and "them".

It's written nowhere that "They said yes; will you come?" and/or "You said yes; will they come?" should be translated as "Sie haben ja gesagt; werden S/sie kommen?". This usage is highly irritating for a German.

Those language 'deficiencies' (English not having a pronoun to distinguish 2nd p. singular and plural, German not differentiating between polite 2nd and ordinary 3rd person plural, Mandarin not having gendered pronouns) are a bit like those potholes: those in your neighborhood you do know, and you know how to effortlessly avoid them on your way home. Those in the other places you don't know, so the ride gets much bumpier.

Whether or not those are 'really' deficiencies or not just properties hinges more on the point of view than on the language in question. Without doubt speakers of some languages will be puzzled about the lack of inclusive vs. exclusive 'we', or the fact that the first person is not gendered in English. Coming to think of it, why do we think we have to distinguish both gender and number in the third person, number but not gender in the first, and neither gender nor number in the second? That's weird! A +1 for singular they!

Colin said,

August 11, 2016 @ 6:44 pm

@Dan: French 'personne' is feminine when it refers to somebody and masculine when it means nobody (e.g. 'une personne contente' versus 'personne n'est content'). I'm not sure what this is supposed to say about French attitudes to men and women.

By the sounds of it, non-gendered language (for example, for non-binary trans people) is rather difficult to accomplish in Romance languages, when even an utterance like 'encantada/o' is effectively declaring the speaker's gender.

Victor Mair said,

August 11, 2016 @ 7:50 pm

tā 他 occurs in old texts, all the way back to the Poetry Classic (roughly 6th c. BC, but incorporating earlier materials and undergoing extensive redaction in later centuries).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Classic_of_Poetry

In its early occurrences, 他 did not function as a third person pronoun, but meant "other". I was taught by my mentors that, when it means "other", one should read 他 as tuó, not tā.

In this sense of "other", 他 gets all entangled with tuó 佗 and tā 它. I shall merely mention that the latter two characters also have other readings with completely different meanings.

tā 他 only emerged as a third person pronoun in the Tang period (618-907). In the premodern period it could indicate either masculine or feminine gender. It was only in the modern period, after extensive, intensive contact with Western literature, that it came to indicate mainly masculine gender. When that happened, writers steeped in Western literature felt the need to devise the character 她 to designate the third person feminine. 他 and 她 were, and still are, both pronounced tā.

Wang Yujiang said,

August 11, 2016 @ 8:27 pm

@Victor Mair

About one hundred years ago, in written Chinese there was one character 他 (ta) which means he/him/she/her/ it. Liu Bannong, a Chinese writer, wrote a famous Chinese poem教我如何不想她 (How Could I Not Miss Her?) in 1920 in London.

How did Liu write “her” in Chinese? There is no a word (means her) in Chinese, so Liu created a Chinese character 她. From that time on 她 has being popular in written Chinese.

Liu tried to imitate English words (he/him/she/her/ it), however 他她它, all of them are still pronounced “ta” in spoken Chinese.

Victor Mair said,

August 11, 2016 @ 9:15 pm

@Wang Yujiang

Excellent confirmation of what I wrote.

thunk said,

August 12, 2016 @ 12:07 am

Didn't we just elect singular "they" as the word of the year in 2015?

I mean, I have no problems with it.

Mark Mandel said,

August 13, 2016 @ 1:03 am

Here is a story about a similar effort now occurring in modern Hebrew:

A camp tries to reinvent the Hebrew language, so transgender kids can fit in

By Julie Zauzmer

Acts of Faith, August 11

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/acts-of-faith/wp/2016/08/11/what-does-a-gender-neutral-kid-call-themself-in-a-gendered-language

Matt said,

August 14, 2016 @ 12:09 am

Not to be that guy, but you absolutely can do this in English: "To love them will be for more than a lifetime." Sure, some people will complain about this use of singular "they." Forget 'em. They don't know what love is. Two hundred years from now people will be quoting the title of your movie as evidence that singular "they" has been accepted for centuries. Linguistic history is written by the winners.

Re 兄妹 as kyōdai, this is certainly etymologically irregular but it's not original to Hunter X Hunter — it's been an established way to indicate a mixed-gender usage of kyōdai for at least a century or so (check Aozora Bunko) and I'd be absolutely astonished if it wasn't used in the Edo period too, although I don't have time to check.

(Rereading Leo's original comment it's not clear that he's actually claiming it is original to that comic, but I thought I'd throw this in anyway for the record.)

Jichang Lulu said,

August 14, 2016 @ 6:38 am

The grapheme 她 existed in pre-modern times as a (rare) variant of either 姐 jiě 'elder sister' or 毑 jiě 'mother' (or grandmother as in Hunan 娭毑 ([ŋai tɕie]?)). It's in the Kangxi dictionary. Liu Bannong 刘半农 didn't create the grapheme, but he's credited with first advocating its use as a pronoun.

Huang Xingtao 黄兴涛 has written a book on 她. Here's an article where he discusses its modern incarnation. Zhang Yun 张赟 has reviewed Huang's book in English. The first modern use in print seems to be by Zhou Zuoren 周作人 (Lu Xun's brother), who in a 1918 translation of a short story by Strindberg spoke approvingly of Liu Bannong's advocacy of 她. Liu's own poem came out in 1920, as Wang Yujiang noted.

This is as good an occasion as any to recommend Zhou Zuoren's essays to anyone who hasn't read them. His views on many social issues ('filial piety' comes to mind) are revolutionary in today's China.

As for the need for a feminine pronoun, I think you can have a different opinion depending on whether translation (of Strindberg of all people) or original Chinese literature is involved. Liu's actual poem is a good example of the 'primacy of orality' that's being discussed on the Pinyin thread(s) (我手写我口 'my hand writes my mouth', which always makes me think of lipstick; as opposed to late 文言文 Literary Chinese is more like 'my hand writes cheques my mouth can't cash'). The text is perfectly understandable if read aloud, except that [GASP] it might not be immediately obvious that the one longed after is a woman.

Liu's poem has been set to music, and sung, by (wait for it) Yuen Ren Chao 赵元任.