Possessive with gerund: Tragic loss or good riddance?

« previous post | next post »

Prescriptive rules are often the result of someone's idiosyncratic attempt to apply logic to a half-understood question of linguistic analysis. In promoting his new book Strictly English, Simon Heffer recently provided us with two examples ("English grammar: Not for debate", 9/11/2010, and "Mr. Heffer huffs again", 9/12/2010).

Such exercises are sometimes motivated by a genuine change in the language, which brings some particular question to the would-be logician's attention. Thus Ben Zimmer pointed out ("Further 'warning'", 9/12/2010) that Mr. Heffer's worry about intransitive warn correlates with a century-long trend of increasing use, originating in the U.S. and spreading to the U.K.

But in some cases, prescriptive confusion has reigned for centuries on both sides of the Atlantic, because usage is mixed and the idiosyncratic logic of self-appointed experts has pointed in different directions. In this morning's Breakfast Experiment™, I planned to discuss one such example and present some historical evidence. But as often happens, the facts turned out to be more interesting than I expected.

Here's the entry for possessive with gerund in the wonderful Merriam-Webster Dictionary of English Usage, courtesy of Google Books:

As the entry points out, for the past few hundred years, people have sometimes written things like "in spite of the book being out of print for many years", and sometimes things like "in spite of the company's not having any intention of issuing a new edition". In fact, the same person may use both forms in the same document — those two examples both come from a single letter written in 1939.

And MWDEU also points out that

From the middle of the 18th century to the present time, […] grammarians and other commentators have been baffled by the construction. They cannot parse it, they cannot explain it, they cannot decide whether the possessive is correct or not.

(Some of) MWDEU's conclusions:

This construction, both with and without the possessive, has been used in writing for about 300 years. Both forms have been used by standard authors. Both forms have been called incorrect, but neither is. Those observers who have examined real examples have reached the following general conclusions: 1. A personal pronoun before the gerund tends to be a possessive pronoun in writing […] 2. The accusative pronoun is used when it is meant to be emphasized. 3. In speech the possessive pronoun may not predominate, but available evidence is inconclusive.

So I thought this would be a good example of temporally stable variation, with a wealth of relevant language-internal factors — and some external factors, including formality, which in turn would be likely to correlate in the usual way with sex, social class, educational level, and so on.

However, my initial explorations turned up some evidence that this linguistic choice may not be so temporally stable after all. It seems to be a case where writing and speech are very different, where writing has been moving fairly fast in the direction of speech for the past half-century or so, and where spoken norms themselves may be moving in the same direction. I'm not sure about all this, but I'll show you the evidence that emerged during this morning's investigations.

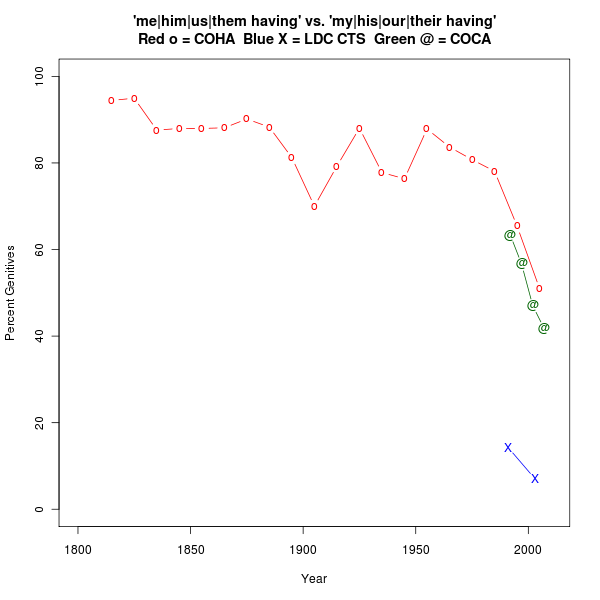

In order to be able to get counts from simple text-string searches, without having to write a clever analysis program or judge individual examples by hand, I decided to start with a single gerund-participle (having) and four pronouns (me|him|us|them vs. my|his|our|their). This avoided the problems of e.g. "(every fiber of) my being" or "(is) it having (any effect?)" — inspection of sample convinced me that the search results were probably pure enough to be useful without further processing.

My data came from Mark Davies' Corpus of Historical American English (COHA), from his Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA), and from LDC Online's conversational English collections. COHA has decade-by-decade material from 1810 to 2000; COCA breaks the last 20 years of this material down by half-decade; and the LDC's CTS material includes one collection from 1991 (Switchboard) and another from 2003 (Fisher).

(There are plenty of problems lurking in all of this material — despite Mark's best efforts, the mix of types of material in COHA obviously changes over time; the demographic mix of speakers in Switchboard and Fisher is somewhat different; other pronouns and other verbs have somewhat different behavior; etc., etc. Still…)

Here are the results expressed in a single graph:

The R script that generated this plot is here — you can get the specific numbers from it.

Some tentative conclusions:

- The difference between writing and speech is very large.

- Since about 1950, writing has apparently been moving in the direction of speech.

- There's some indication that spoken norms may also be changing, in the same anti-genitive direction.

- It's possible that there was a change in the anti-genitive direction in the late 19th century, perhaps held up by prescriptive forces (?).

I think that this is suggestive enough to warrant further investigation, on a scale not feasible during a single breakfast period. (In particular, it would be important to verify that the apparent trend in the COHA/COCA numbers exists independent of the gradually increasing proportion of material from transcripts and the like.)

These issues are discussed in CGEL on p. 1192, where it's again noted that "Genitives are more likely to occur in formal than in informal style", and that

Modern usage manuals generally do not condemn non-genitives altogether (as Fowler did in early work), though they vary in their tolerance of them, the more conservative ones advocating a genitive except where it sounds awkward, stilted, or pedantic […]

Given the apparently rapid change over the past half-century, I'm surprised that this question has not generated more viewing with alarm and drawing of lines in the sand.

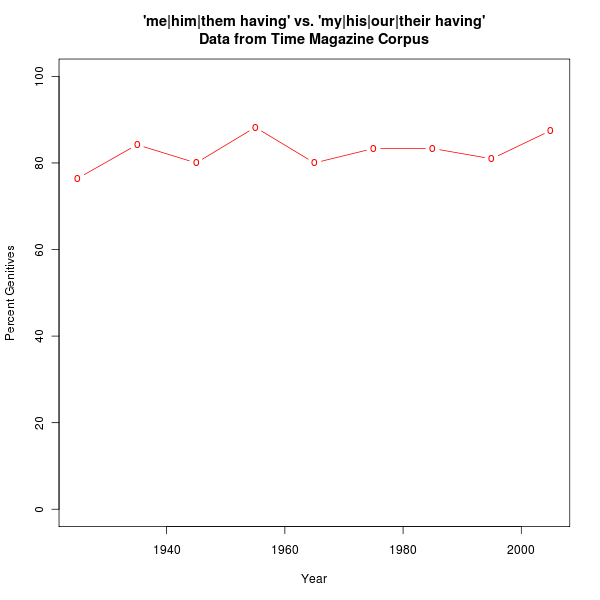

[Note: one piece of evidence in favor of continued stable variation is provided by the TIme Magazine Corpus. The overall numbers for this pattern are small — 8 to 19 total hits per decade — but such as they are, the proportions don't seem to have changed much since the 1920s:

R script here.]

[Update — Ian Preston points out that Mr. Heffer has in fact spoken up, Canute-like, against the tide of change in this case.]

The Ridger said,

September 18, 2010 @ 10:05 am

I always thought there had to be a difference, but that difference really boils to down using the objective when the pronoun is meant to emphasized.

In spite of his running around, he's a good man vs In spite of him running around most men don't

linda seebach said,

September 18, 2010 @ 10:09 am

You could have added an example "where the same person may use both forms in the same document" by writing "has not generated more [people] viewing with alarm and [their] drawing of lines in the sand." And probably set the record for how close together the two forms can be.

But does it count if you do it on purpose?

mgh said,

September 18, 2010 @ 10:51 am

Can you give some examples of the results your search turned up?

[(myl) In the case of COCA and COHA, you can try for yourself — just follow the links. LDC Online will let guests search Switchboard, so you can try that too. In the Fisher English collection, there are 30 hits for "me having", and a quick scan shows that some of them are definitely in some sense a wrong fit, e.g.

but the majority are valid hits. As usual with simple string searches like this, the counts are at best a reasonable proxy, and we'd want to check by hand, or write a more discriminating filter, or both.]

Google search for "me having" gives results like "Mom caught me having sex" or "Hubby's ex hates me having 'big talks' with stepdaughter".

The former, obviously, doesn't allow "my having" (*Mom caught my having sex) and to my mind the latter also has a slightly different meaning than it would with "my having" (the hate is focused on the person more than the action).

Jerry Friedman said,

September 18, 2010 @ 10:59 am

One distinction is that the objective is very informal in the subject of a clause.

Him gaining power was Doe's greatest fear.

She wondered whether them joining the effort would have any benefits.

Neither of those strikes me as likely in any kind of formal context.

Brett R said,

September 18, 2010 @ 11:05 am

In the British National Corpus (1970s-1990s), genres break out this way:

Spoken: 13% genitive

Fiction: 73%

Magazine: 10%

Newspaper: 39%

Non-acad: 43%

Academic: 94%

Misc: 94%

Jerry Friedman said,

September 18, 2010 @ 11:18 am

I mentioned She wondered whether them joining the effort would have any benefits.

I think it might not be as strongly informal as I said, though I still see it as less likely in formal contexts than the usual examples in predicates.

michael farris said,

September 18, 2010 @ 1:15 pm

Him gaining power was Doe's greatest fear.

His gaining power was Doe's greatest fear.

She wondered whether them joining the effort would have any benefits.

She wondered whether their joining the effort would have any benefits.

I think there might be a semantc difference in these pairs. For me, the one with the oblique refers to a potential situation (he might or might not gain power, they might or might not join the effort) while the sentences with the possessives implies that he is in the process of gaining power and they've joined the effort respectively.

For sure a lot of the time I don't perceive any difference but in certain contexts I do. Does anyone else?

Alexander said,

September 18, 2010 @ 2:38 pm

Horn (1975), Abney (1987), Portner (1992) and many others have reported grammatical contrasts between the "acc-ing" and "poss-ing" forms. Here are a few:

1ai) That's the thing I was bothered by him saying

1aii) What were you bothered by him saying?

1bi)?*That's the thing I was bothered by his saying.

1bii)?*What were you bothered by his saying?

2a) The man whose suddenly leaving bothered you was my brother.

2b) *The man who suddenly leaving bothered you was my brother.

3a) *They were offended by my saying that, and his too.

3b) (?)They were offended by me saying that, and him too.

4a) John coming and Mary leaving bothers (*bother) me.

4b) John's coming and Mary's leaving bother (?bothers) me.

Janice Byer said,

September 18, 2010 @ 4:20 pm

Michael Farris, yes, I parse the two options just as you well describe. Same as you, I don't always perceive a difference, but when writing, I'm occasionally aware of choosing one or the other based on your exact reasoning.

Gordon Campbell said,

September 18, 2010 @ 4:23 pm

Michael Farris: I was thinking along the same lines and was about to post a comment when I saw yours. The construction (for example) "She disapproves of his philandering" suggests–to me–that he philanders and she disapproves, but "…him philandering" could refer to hypothetical rather than actual philandrification.

kaf said,

September 18, 2010 @ 4:47 pm

Maybe we can explore the participle-gerund difference by trying to understand when a word can serve as a gerund and when it cannot. For example, you can say "She doesn't like me singing" (participle — the process of singing) and "She doesn't like my singing" (gerund – someone off-key). You can say "This is a photo of me singing" (p – the act) but you cannot say "This is a photo of my singing" (g – the "thing") because you can hear singing and see someone doing it but you cannot see the sound. If you're a baseball fan, you can enjoy "watching him batting and fielding" (p) and you also can enjoy "watching his batting and fielding" (g). Try substituting other words such as swimming, eating, throwing, listening, etc., in such constructions to perceive the distinction. Many -ing words don't seem to work as gerunds. If you examine examples in the Merriam-Webster insert shown above and think about the singing example, you may be able to tell when the -ing word is a participle and when it is not — and consequently when the writer appears to have chosen the wrong pronoun form. In one case (O'Connor letter 1956), the pronoun looks like it should have been reflexive.

Jerry Friedman said,

September 18, 2010 @ 6:48 pm

@Alexander: Your example is the only hit on whose suddenly leaving, and there were no hits on whose suddenly deciding or whose suddenly taking. That's as far as I went, but I'm not sure your 2a is any more grammatical than 2b.

J. Goard said,

September 18, 2010 @ 9:25 pm

@Michael, Janice, Gordon:

I would attribute this to the definiteness (I prefer "higher accessibility", but perhaps "definit-i-ness") of the genitive construction. It's not exactly definite, since you can say things like (1) without the addressee having a unique referent in mind; however, if you say (2a) instead of (2b), you seem to make the odd implication that none of your other friends are cool.

(1) My friend is coming over.

(2a) My cool friend is coming over.

(2b) A cool friend of mine is coming over.

But this caveat aside, the examples you cite strike me as equivalent to the contrast between mass nouns with no article versus with the definite article, e.g.:

(3a) I'm worried about embezzlement in my firm.

(3b) I'm worried about the embezzlement in my firm.

The participial construction seems to lack typical (nouny) referential status, thus avoiding the definite/indefinite distinction. However, as kaf's comment shows, this is far from the only distinction between the two constructions.

Julie said,

September 19, 2010 @ 1:05 am

"Whose suddenly deciding" sounds wrong to me. I read "deciding" as a noun requiring an adjective. "whose sudden deciding," as opposed to "who, suddenly deciding…."

David Denison said,

September 19, 2010 @ 3:51 am

In case it's still of interest, there's some discussion of variable and changing case before a gerund in my chapter on late ModE syntax (1998: 268-72), together with references to previous studies. Most are from pre-corpus days, though their discussions are often illuminating, but one – Dekeyser (1975) – has counts for the nineteenth century.

Denison, David. 1998. Syntax. In Suzanne Romaine (ed.), The Cambridge history of the English language, vol. 4, 1776-1997, 92-329. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pflaumbaumq said,

September 19, 2010 @ 6:09 am

@ Alexander

Your example:

3b) (?)They were offended by me saying that, and him too.

is completely natural to me. The only issue is an ambiguity re the 'him' – were they offended by him, or was he offended by me too (i.e. use of 'him' in subject position)?

jo said,

September 19, 2010 @ 8:17 am

@Pflaumbaumq

For Alexander's 3b, I think we have to take the "?" judgement as being for the interpretation where "they" are offended by "him" too, rather than "him" being offended by "me"; this is fairly clear if you compare with 3a.

Obviously there are some individual differences here, but I find (what I assume to be) the intended reading very difficult to get from 3b, and transparent in 3a, even though 3a is ungrammatical for me. Incidentally, 3a-type sentences are fine if a non-gerund noun is used, e.g. "They were offended by my haircut, and his too.".

Matt McIrvin said,

September 19, 2010 @ 8:35 am

I have a dim memory of my reading a fictional account of a teacher's berating a student over his getting this distinction supposedly wrong, but I cannot remember what the book was or which direction the supposed error was in.

Alexander said,

September 19, 2010 @ 10:21 am

The inclusion of an adverb is a tool of the trade in the study of nominals, popularized by Vendler 1967 ("Facts and Events"): (i) "Brutus's stabbing of Caesar", where the 'direct object' has "of" takes modifers in adjectival form: "Brutus's brutal stabbing of Caesar"; whereas (ii) "Brutus's stabbing Caesar" where the 'direct object' is bare, takes modifiers in adverbial form: "Brutus's brutally stabbing Caesar." (The "ACC+ing" gerunds also take adverbs.) Therefore, the use of adverbial modifiers is used in grammatical argumentation to exclude the type (i) gerunds, even in the absence of a 'direct object' ("his suddenly leaving"). This is often important, since these differ significantly from the others in both syntax (e.g. the "of" contrast) and meaning (according to Vendler, in denoting events, versus facts). So if one wants to assess Abney's claims about contrasts between different types of interrogative gerunds, it helps to include modifiers.

Ian Preston said,

September 19, 2010 @ 4:25 pm

I hope that you are aware that the inestimable Mr Heffer has in fact vouchsafed a ruling on this particular question:

iching said,

September 19, 2010 @ 11:47 pm

An interesting topic! Commenters have pointed out 3 possible (nuanced) distinctions between the genitive+gerund and oblique+gerund constructions:

1. Formal/written vs informal/spoken

2. Emphasis on the action vs the actor

3. Actual vs potential

I would like to suggest another possibility (possibly related to 2.

4. Degree of responsibilty/control of the actor for the action

e.g. "His suddenly leaving disappointed me" (which seems to focus on disappointment with the actual leaving which might have been unavoidable) vs "Him suddenly leaving disappointed me" (which focuses more on disappointment with the person himself and his deliberate course of action).

To summarise my thoughts on the two constructions may I offer 5 sentences and my parsing of them:

(1) His sudden leaving caused an uproar. Here "leaving" is noun-y and so is modified by an adjective ("sudden") cf. "His sudden departure caused an uproar, i.e. the result of the action (the leaving or departure) caused the uproar rather than the act of leaving itself.

(2) His suddenly leaving caused an uproar. Here "leaving" is verb-y and so is modified by an adverb ("suddenly"), i.e. the action of leaving, which he performed (rather than the result, his disappearance), caused an uproar.

(3) Him suddenly leaving caused an uproar. The fact that he (in particular) performed the action of leaving is what caused an uproar.

(4) He (suddenly leaving) caused an uproar. I tried to think of an example where the pronoun could be in the nominative case and this is all I could think of. Here the cause of the uproar is unambiguously the person, and the action of leaving may well have been incidental or irrelevant.

(5) * Him sudden leaving caused an uproar

Only (5) seems ungrammatical to my ears.

I have some twinges of doubt about whether all these supposed nuances of meaning are real or imagined…

Twitter Trackbacks for Language Log » Possessive with gerund: Tragic loss or good riddance? [upenn.edu] on Topsy.com said,

September 20, 2010 @ 1:42 am

[…] Language Log » Possessive with gerund: Tragic loss or good riddance? languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=2637 – view page – cached Prescriptive rules are often the result of someone's idiosyncratic attempt to apply logic to a half-understood question of linguistic analysis. In promoting his new book Strictly English, Simon Heffer recently provided us with two examples ("English grammar: Not for debate", 9/11/2010, and "Mr. Tweets about this link […]

Paul Portner said,

September 20, 2010 @ 1:02 pm

Hi – Regarding the potential semantic difference mentioned by comments above, in my dissertation (1992, UMass) I argued for a definiteness distinction. This distinction (if it's real at all) only comes out in an otherwise non-factive, non-topical context. One example (p.110):

– Mary didn't discuss John/John's coming to visit her.

I judged the possessive subject to presuppose that the case where John comes to visit her is under discussion. This difference also feeds into the availability of quantificational readings for gerunds (106-7).

– Joyce usually dreams about Mary/Mary's shouting at her.

My claim was that, with the possessive, the sentence can mean "Most of the time, when Mary shouts at her, Joyce dreams about it." This is where the discussion made contact with the hot semantic topics of the day.

This many years later, I'm still convinced there's a semantic difference (for me, and apparently for a number of other speakers), but I wonder if more modern ideas about definiteness and presupposition could allow us to state what it is more accurately.

Ellen K. said,

September 20, 2010 @ 2:04 pm

@Paul Portner.

I do think there's a definite difference in your second example. To me, as I read it, "Mary's shouting at her" is a real world event, that comes up in Joyce's dreams, where as "Mary shouting at her" describes the content of Joyce's dreams.

I think, though, in most examples, any difference in meaning is subtler and less reliable. In your first example, each gives me a different impression as far as whether it's more likely something that already happened (possessive), or something in the future (non-possessive), but neither gives a definitive impression.

David Marjanović said,

September 22, 2010 @ 11:36 am

(Cross-posted from Language Hat.)

It's reanalysis.

When "I resent him doing that", I resent him, not the doing; and the doing isn't a gerund anymore, it's a present participle. At least inside my skull.

This is he, looking out of the window.

I see him looking out of the window.

I resent him looking out of the window.

Of course, my native German is probably biasing me. A literal translation of "his looking out of the window" would be sein Aus-dem-Fenster-Schauen; that's just too convoluted to bear. It's icky and squicky.

Warsaw Will said,

November 13, 2011 @ 12:41 pm

@mgh

'Google search for "me having" gives results like "Mom caught me having sex" or "Hubby's ex hates me having 'big talks' with stepdaughter".'

Is the first example not a case of an object complement rather than a gerund? She caught me in the act of having sex. A couple of grammar websites use a similar example -"I noticed you standing in the alley last night", saying we probably wouldn't say 'your' here. I disagree; we'd never say 'your' here, for the same reason.

@Jerry Friedman

I think you've hit on it when you suggest that non-possessive personal pronouns in subject position are more informal than when in object position. To me, "Me swearing really bothers my aunt", is a degree of formality lower than, "My aunt doesn't like me swearing." – a position (concerning personal pronouns) also suggested in New Fowler's, while noting (with a few reservations) that, 'The possessive with gerund is on the retreat'.

Jim Weigang said,

April 17, 2013 @ 4:07 pm

@ Matt McIrvin

Perhaps this?

"Anthony, my dear, foolish, bright, crazy, lazy beamish boy, how I shall love and hate to see your back."

"Would you like me to leave sooner? Do you object to me staying till then?"

"Object to _my_ staying. The subject of a gerund is modified in the possessive," she said, and burst into tears.

Watching her run out the back door and into the yard, I knew that my following her would have been not only useless, but inexcusable. [p.150]

— Peter De Vries, _Slouching Towards Kalamazoo_ [1983]

Robert Simms said,

April 27, 2014 @ 1:40 pm

Gordon Campbell said:

"She disapproves of his philandering" suggests–to me–that he philanders and she disapproves, but "…him philandering" could refer to hypothetical rather than actual philandrification.

Other than Philandrification's being an example of supposedly George-Bush-ification, Campbell's example suffers from another problem. If one meant to say that "he," whoever he is, had not actually philandered, and that "she," whoever she is, disapproved of his even thinking about it, then the writer should have rephrased his sentence to make that meaning clear. Just because you can put together a sentence that could be read two ways depending on whether or not you use a possessive before a gerund or don't, doesn't mean that both ways are structurally sound. When in doubt, revise.