Too like the gender

« previous post | next post »

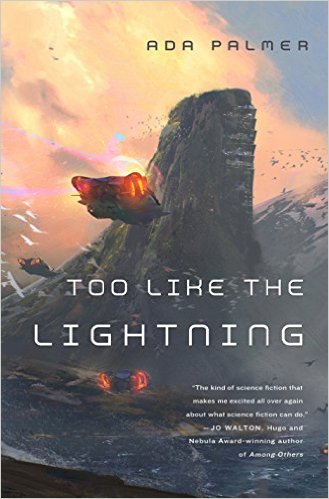

Is this the future of English pronouns? Ada Palmer's Too Like the Lightning takes place in a world where he/she is as quaintly obsolete as thee/thou. From the book's opening:

You will criticize me, reader, for writing in a style six hundred years removed from the events I describe, but you came to me for explanation of those days of transformation which left your world the world it is, and since it was the philosophy of the Eighteenth Century, heavy with optimism and ambition, whose abrupt revival birthed the recent revolution, so it is only in the language of the Enlightenment, rich with opinion and sentiment, that those days can be described. You must forgive me my ‘thee’s and ‘thou’s and ‘he’s and ‘she’s, my lack of modern words and modern objectivity. It will be hard at first, but whether you are my contemporary still awed by the new order, or an historian gazing back at my Twenty-Fifth Century as remotely as I gaze back on the Eighteenth, you will find yourself more fluent in the language of the past than you imagined; we all are.

You will criticize me, reader, for writing in a style six hundred years removed from the events I describe, but you came to me for explanation of those days of transformation which left your world the world it is, and since it was the philosophy of the Eighteenth Century, heavy with optimism and ambition, whose abrupt revival birthed the recent revolution, so it is only in the language of the Enlightenment, rich with opinion and sentiment, that those days can be described. You must forgive me my ‘thee’s and ‘thou’s and ‘he’s and ‘she’s, my lack of modern words and modern objectivity. It will be hard at first, but whether you are my contemporary still awed by the new order, or an historian gazing back at my Twenty-Fifth Century as remotely as I gaze back on the Eighteenth, you will find yourself more fluent in the language of the past than you imagined; we all are.

A bit later, constrained by that narrative device to use they in dialogue and quotation, but he/she in narrative description, the narrator faux-apologizes again:

Does it distress you, reader, how I remind you of their sexes in each sentence? ‘Hers’ and ‘his’? Does it make you see them naked in each other’s arms, and fill even this plain scene with wanton sensuality? Linguists will tell you the ancients were less sensitive to gendered language than we are, that we react to it because it’s rare, but that in ages that heard ‘he’ and ‘she’ in every sentence they grew stale, as the glimpse of an ankle holds no sensuality when skirts grow short. I don’t believe it. I think gendered language was every bit as sensual to our predecessors as it is to us, but they admitted the place of sex in every thought and gesture, while our prudish era, hiding behind the neutered ‘they,’ pretends that we do not assume any two people who lock eyes may have fornicated in their minds if not their flesh. You protest: My mind is not as dirty as thine, Mycroft. My distress is at the strangeness of applying ‘he’ and ‘she’ to thy 2450s, where they have no place. Would that you were right, good reader. Would that ‘he’ and ‘she’ and their electric power were unknown in my day. Alas, it is from these very words that the transformation came which I am commanded to describe, so I must use them to describe it. I am sorry, reader. I cannot offer wine without the poison of the alcohol within.

Third-person singular animate pronouns are not the only vocabulary items for which the narrator apologizes:

Danaë came to her husband’s side. Do not chide me, reader, for using the gendered ‘husband’ when she stands so close, sheltering against him as she gazes up into his face with her brilliant, pleading blue eyes edged by maternal fear. Our age’s neutral ‘partner’ rings false when her every touch and gesture makes such intentional display of ‘wife.’

And gendered clothing is also an issue:

I cursed myself inside, although, looking back, I forgive myself now. She was irresistible. Remember, reader, though I use archaic words, I am not from those barbaric centuries when men and women wore their gender like a cockerel’s plumes, advertising sex with every suit and skirt. Growing up, I saw gendered costume on the stage, in art, pornography, but to see it in real life is unbearably different: her shallow breaths within constricted ribs, her round French breasts threatening to overflow the low Japanese silks. Here, as Andō wraps his arm around her waist, the costume makes me see them in my mind: the husband wrenching the kimono back to bare the honey-wet vagina. You see now, reader, why, to tell this history, I must say ‘he’ and ‘she.’ Danaë is a thing long thought extinct, reviving out of time ancient venoms perfected by a hundred generations of gendered culture. We around her— from my weak self to the gaping guards— grew up with no inoculation against this pox we thought our ancestors had vanquished. Movies and histories gave us just enough exposure to learn these ancient cues, weakness without resistance, and we can no more unlearn them than you could unlearn your alphabet when facing an unwelcome word.

There's more, of course — in particular, the narrator apologizes again for not using he/she to express affective interpersonal reactions rather than biological sex:

I realize, reader, that I should apologize for my confusing language, since if my ‘he’ and ‘she’ mean anything then certainly this sweet and gentle Cousin in her flowing wrap should be ‘she.’ In this case, alas, I am commanded by an outside power to give Carlyle the masculine, to remind you that this long-lost scion is a prince, not princess, a fact which matters in the eyes of some, and of the law. But I shall do my best to remind you often that a Cousin’s maternal heart beats beneath Carlyle’s broad chest, and I promise, reader, to be consistent in making other Cousins ‘she.’

Or the opposite:

Innocent reader, I take comfort in your confusion, for it is a sign of healthy days if you are illiterate in the signal-flags of segregation humanity has worked so hard to leave behind. In certain centuries these high, tight boots, these pleats and ponytail might indeed have coded female, but I warned you, reader, that it was the Eighteenth Century which forced this change upon us, and here it stands before you. You saw already Princesse Danaë, with the costume of Edo period Japan, and its comportment, too: modest, coquettish, fragile, and proficient at making the stronger sex risk death for her. Can you not recognize the male of that species? Though French this time, rather than Japanese. Perhaps you argue that a gentle‘man’ of that enlightened age is effeminate, his curls and silks, his poetry and dances, and you are right if we apply the standards of a Goth or other proud barbarian. But would you then oblige me to call all such gentlemen ‘she’? The Patriarch? George Washington? Rousseau? De Sade? Shall I call the Divine Marquis ‘she’? No, good master. To understand what follows, you must anchor yourself in this truth, that, by the standards of the era which sculpted him from childhood, the woman Dominic Seneschal is the boldest and most masculine of men.

But you should read it for yourself — there's also theology, politics, crime, and flying cars…

Jim said,

May 18, 2016 @ 6:43 am

I think it's quite plausible English will replace entirely "he" and "she" with "they" in the near future, not because of some social obliteration of concepts of gender but simply as part of what seems to be a general ongoing trend in English to replace singular pronouns with plural ones.

S Frankel said,

May 18, 2016 @ 8:47 am

We don't see any trend to replace the first-person singular with the plural, but that's an interesting observation for the 2nd and 3rd persons. (We are not a monarch, incidentally.)

There are, obviously, plenty of language with only a single, non-gendered 3rd-person singular pronoun. These may have other ways of indicating gender, but I spend a lot of time around Javanese/Indonesian speakers who are fluent in English, and they occasionally mix up "he" and "she" when they're not thinking about grammar.

languagehat said,

May 18, 2016 @ 8:51 am

Sounds like a throwback to Looking Backward and all the rest of the hideous utopias of a century and more ago, and their equally tedious descendants in the sf of the 1920s: "As you know, our ancestors had the foolish habit of [blah blah blah], which we have overcome through the great inventions of [blah blah blah]…" Ann Leckie has the right idea: just toss the reader into the genderless world and let her sink or swim.

David Fried said,

May 18, 2016 @ 9:30 am

Sounds tedious. And "thee" and "thou" had gone extinct by the 18th century except among Quakers and in dialect.

leoboiko said,

May 18, 2016 @ 9:59 am

@languagehat: But, apart from gender issues, I love pastiches in exactly this moralistic, faux-Victorian ", dearest Reader, " style, where the narrator cannot help but keep offering ætheral judgements-from-above all the friggin time. I love it in the language, in the words, which I find delightful and charming. Others may find it tedious, but I enjoy watching the preaching be aimed the other way.

Robert Coren said,

May 18, 2016 @ 10:04 am

I find myself reading these excerpts as rather heavy-handed satire of 21st-century trends in avoiding gendered pronouns.

languagehat said,

May 18, 2016 @ 10:04 am

Well, you would appear to be the ideal audience for this hortatory (or mock-hortatory, as the case may be) work; go for it!

languagehat said,

May 18, 2016 @ 10:05 am

(Er, that was to leoboiko; I can't bear the @ style, but it would have come in handy here.)

Adam Roberts said,

May 18, 2016 @ 10:41 am

"Ann Leckie has the right idea: just toss the reader into the genderless world and let her sink or swim".

Leckie's Ancillary books are great, but replacing all pronouns with 'she' and 'her' is hardly creating a genderless world. It does a good job of startling us out of our generic he/his complacency, sure: but these are surely gendered words.

languagehat said,

May 18, 2016 @ 11:01 am

No, you've missed the point. They are not gendered words to the person/AI who/that is using them; the fact that they are gendered words to the reader is exactly what causes the salutary cognitive dissonance.

KeithB said,

May 18, 2016 @ 11:06 am

David Freid:

Thee's and Thou's while addressing the Deity existed in prayers until relatively recently.

D.O. said,

May 18, 2016 @ 11:07 am

OK. I didn't post this comment before, but Language Hat's has induced me.

When in a not-so-distant future the coastal communities will be washed away, droughts and hurricanes devastate the agriculture, war of all against all will end in a nuclear annihilation, a few scattered bands will scrap the Earth for leftovers of medium-level technology (high level will be out of the reach) and one of a few literate people will find this book (LL will be unavailable, internet goes kaput), he will read it in despair thinking "what the hell she is talking about?"

Mark Mandel said,

May 18, 2016 @ 11:33 am

I know Ada Palmer as the founder of the a cappella group Sassafrass [sic], whose music I recommend highly. http://www.sassafrassmusic.com/group/about/

Felila said,

May 18, 2016 @ 11:44 am

The book is a cliffhanger, which is NOT advertised.

I bounced off the worldbuilding. Implausible in so many ways.

un malpaso said,

May 18, 2016 @ 5:34 pm

Seems like an interesting read, but the "18th-century style" seems to have some glitches. In a way I suspect that's appropriate.

Keith M Ellis said,

May 18, 2016 @ 7:24 pm

@LL, it seems so overwrought that my first impression is that surely the ultimate intention is ironic. But maybe not. I like the idea, though, of a future narrator confidently and pompously misunderstanding many aspects of the 21st century culture(s) as a means of subtextually criticizing how we tend to think about the past (and, conversely, imagine the future).

AntC said,

May 18, 2016 @ 7:52 pm

@leoboiko the narrator cannot help but … all the friggin time. I indeed find tedious. What became of "show it, don't tell it"?

In Tristram Shandy it's hilarious sending the reader back nearly a whole chapter to pay closer attention to why his mother is a Catholic (actually revealed on the previous page). In Don Quixote you can feel Cervantes' disdain of his imitators. In Gargantua it's all part of the play to berate the reader for their lack of credulity. They were pushing the boundaries of a new form.

And I suppose ngrams will make a liar of me, but birthed as a transitive? [middle of the first excerpt]

Vanya said,

May 19, 2016 @ 3:15 am

I don't know. The idea that a shift to genderless pronouns represents "progress" just seems incredibly parochial to me, the mindset of people who are only familiar with Indo-European languages. Why not just learn Turkish?

RickR said,

May 19, 2016 @ 5:56 am

@AntC

"birthed as a transitive?"

The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, third edition (1992), paper edition, gives the definition of "birth" as a transitive verb, with the note that "until recently, the use of 'birth' as a verb meaning 'to bear (a child)' has been confined to Southern speech" and gives an example from Marjorie K. Rawlings.

The online edition give a definition as a transitive verb and simply notes it as "Chiefly Southern US".

Which is probably why I, raised in northern Florida, am familiar with the usage

Levantine said,

May 19, 2016 @ 6:00 am

To Vanya's point, one doesn't even have to leave the Indo-European family behind: Persian too has only genderless pronouns.

Graeme said,

May 19, 2016 @ 7:39 am

This 21st century reader is lost. The narrator is in the 25th century talking to whom about what?

[(myl) The narrator is talking to their 25th-century contemporaries about a complex politically-entangled 25th-century crime.]

Martha said,

May 19, 2016 @ 9:29 am

I roll my eyes at this book. Would someone living now write a book about the 1400s and try to write the way people spoke at that time (outside of dialogue)? Maybe people do that, but I've never read anything of the sort and wouldn't be interested in doing so.

I'm not from the South, but if "birth" is going to be a verb, it has to be transitive. "I don't know nothin' 'bout birthin' no babies!"

Rodger C said,

May 19, 2016 @ 11:24 am

In Gargantua it's all part of the play to berate the reader for their lack of credulity.

Misnegation?

J.W. Brewer said,

May 19, 2016 @ 11:27 am

I agree with Vanya & Levantine, but with this additional note. People who rather self-consciously avoid gendered pronouns in current Anglophone society often tend to be those with self-consciously "progressive" views about gender roles etc. So it is easy to assume that if that pattern of language use in the future spreads and becomes nigh-universal it would signal that those concurrent political views have likewise become nigh-universal. But it seems equally plausible that the language-use pattern could spread beyond its current self-conscious advocates and be widely adopted by people without those political attitudes and thus lose its social-signal function, with the end-point being a society that has eliminated gendered pronouns but not gender roles. It could be a bit like one feature of the euphemism treadmill, where the "new" and preferred-by-activists label for a group originally serves as an in-group signal that the user cares more than the average person does about the particular cause but then loses that function if the campaign to ditch the old label in favor of the new one actually succeeds and the wider language community adopts the new one (with any hope that convincing the wider language community to change lexemes would then lead to a change in their substantive attitudes toward the referent of the lexeme often proving to have been magical thinking).

To Martha's point: there have been well-known modern American novelists (outside the "genre" ghetto) who deliberately wrote books with a historical setting in a pastiche or approximation of a period prose style. John Barth's The Sotweed Factor and Erica Jong's Fanny are two that come to mind, and I expect there are others. Whether the aesthetic effect created by this approach is worth the extra effort it takes the reader to wade through it is presumably a question on which opinions vary.

Levantine said,

May 19, 2016 @ 12:33 pm

J. W. Brewer, I quite agree that non-gendered pronouns are not in themselves an indicator of a "progressive" ideology. If they were, Turks and Iranians would be incapable of sexism.

AntC said,

May 19, 2016 @ 8:12 pm

@RickR thanks: birth as a verb marked "dated or Regional". I'm BrE.

@Martha: thanks, From 'Gone with the Wind'. Is that quote in the movie? I gave up slogging through the book.

Narmitaj said,

May 20, 2016 @ 6:35 pm

Sf writer John Scalzi invites other sf authors to promote their Big Ideas for their books on his blog, and a recent one was Ada Palmer on Too Like the Lightning, where, among other things, she says she wanted "to write something that would feel alien the way Voltaire feels alien, by writing in a classic SF setting but with an 18th century question palette."

http://whatever.scalzi.com/2016/05/11/the-big-idea-too-like-the-lightning/ to see what she was aiming to do.

Stephen said,

May 21, 2016 @ 10:31 am

Rarely have I had such a negative reaction to reading excerpts from a work of literature. I think this is what the word "twee" was invented to describe. Also, the phrase "I threw up a little in my mouth." And "Good Lord, what drivel."

Pietro Toniolo said,

May 25, 2016 @ 9:26 am

It reminds me of this article from Hofstadter: https://www.cs.virginia.edu/~evans/cs655/readings/purity.html

Anyway, english only has pronouns that differ in gender. The remaining part of the grammar is mostly gender-neutral. For a language strongly gender-oriented like my italian, where nearly every name and adjective must be specified as masculine or feminine, we do not feel this to be a problem…