Incipient syllabaries

« previous post | next post »

Yesterday afternoon, Liwei Jiao went to a Chinese restaurant in South Philadelphia and ordered three dim sum dishes. Below is a photograph of the order taken down by the waitperson. The restaurant is called Wokano and it is located at 12th St and Washington Ave.

What are the three items written down on the order?

The waitperson scribbled the following:

xiàjiāo 下交 (lit., "lower intersect")

xiàcháng 下长 (lit., "lower long")

chābāo 叉包 (lit., "fork package")

Those stand respectively for:

haa1gaau2 / xiājiǎo 虾饺 ("shrimp dumplings")

haa1coeng4*2fan2 / xiāchángfěn 虾肠粉 ("shrimp rice noodles")

caa1siu1baau1 / chāshāo bāo 叉烧包 ("barbecued pork buns")

So the dishes Liwei ordered are #1, #17 and #20.

What can we say about their principles of notation? Of course, it is obvious that they are willing to truncate terms radically. The main thing, however, is that they are more interested in the sounds of characters than their meanings. This is a phenomenon that has persisted throughout the history of Chinese writing, apart from the formal adoption of simplified characters, many of which are formed by resorting to this principle.

For example, I have often seen 午 wǔ ("noon") written for wǔ 舞 ("dance") and jiāng 江 ("[Yangtze] river") written instead of jiāng 疆 ("border"). In both cases, although the original characters are common, they never received an official simplified form, so the simpler characters, regardless of their completely unrelated meaning, were informally (i.e., unofficially) used to replace the complicated characters.

This principle of borrowing a simpler character to replace a more complicated character, regardless of its meaning, was often resorted to throughout Chinese history. Naturally, in transmitted texts, editors would strive to restore the "correct" forms, but in inscriptions — as, for example, on steles of the Six Dynasties period (222-589) — such simplified replacement forms engraved in stone survive till today.

Another method for avoiding having to write all the strokes of a complicated, yet common, character is just to take a part to stand for the whole. For instance, people often have to write jiē 街 ("street"), but its twelve staccato strokes are a nuisance. Consequently, people who are jealous of their time will substitute for 街 just the rightmost component, chù 亍 ("take small steps; step with the right foot"). 亍 is the right half of Kangxi radical 144 — xíng 行 ("walk; move; travel") — the left half being chì ㄔ ("step with the left foot"; radical 60, which I learned as shuāngrén páng 雙人旁 ("double man at the side"). Together chì 彳and chù 亍 form the binom chìchù 彳亍("trudge; amble; plod").

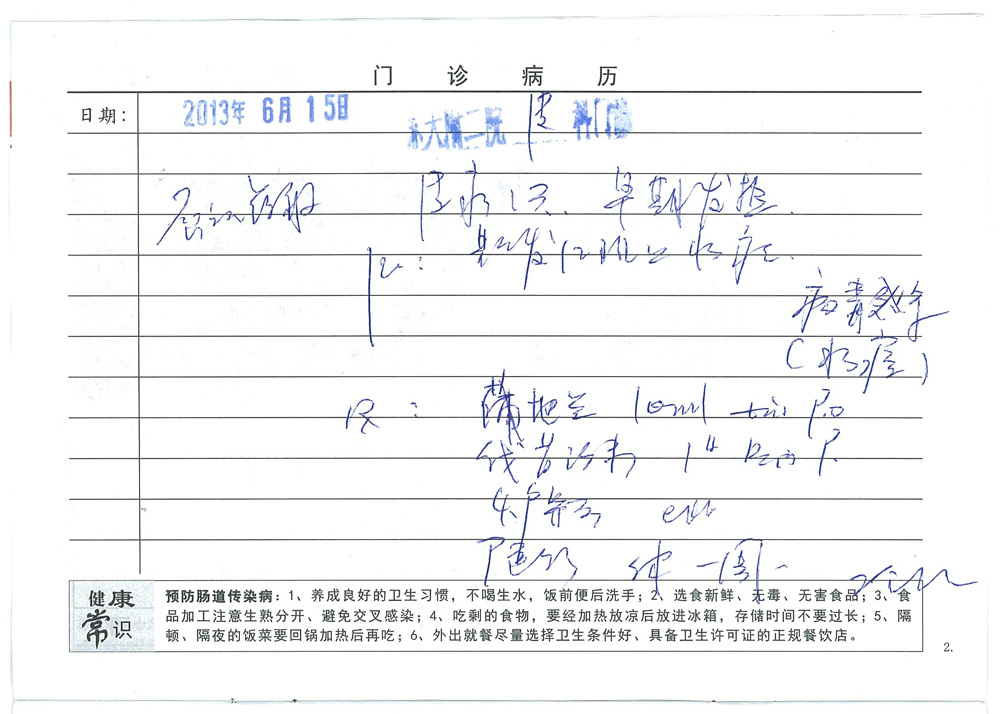

Another stenographic writing system restricted to a particular profession in China is that employed by physicians. Although I will not describe or explain it in detail, I give one instance of it in action as displayed on this page of a hospital casebook for one of my students who was afflicted with varicella two years ago:

Because of the extreme cursiveness, abbreviations, and so on, most outsiders can only catch a little of what is written in such casebooks, but I'm told that Chinese doctors — even those who don't know each other — can readily read and understand the notations.

For doctors' handwriting and abbreviations in the West, see here and here.

For a classic example of a person with a PhD forgetting how to write the characters for "shrimp" and other common words, see:

"Dumpling ingredients and character amnesia" (10/18/14)

Here we observe that the hapless shopper substituted for the forgotten characters not homophonous characters but their sounds spelled out in pinyin.

For another example of Chinese restaurant shorthand, see:

"General Tso's chikin" (6/11/13)

Many people have asked: why didn't the Chinese script evolve into a syllabary or other type of phonetic script (e.g., kana, hangul, Quốc ngữ)? I think that the main obstacle to phoneticization in China has been the enormous prestige of the characters under the custody of the literati. Now that the imperial examination system, which sustained the traditional characters for more than two thousand years, has ended for more than a century and we are witnessing character amnesia, romanized inputting, and emerging digraphia, the barriers to phoneticization have been lowered and the factors promoting it have been enhanced. As a matter of fact, at least one large Sinitic syllabary did develop in China, the celebrated nǚshū 女书 ("women's writing"). I suspect that similar kana-like experiments happened in China repeatedly to one degree or another, but that they all aborted under the dominance of the elite script. However, chances are good that, as described above and in many Language Log posts, phoneticization will continue apace. N.B.: This is not something that I am advocating. It is happening because of natural social, technological, and cultural processes.

[Thanks to Rebecca Fu, Fangyi Cheng, and Yixue Yang]

Anschel Schaffer-Cohen said,

December 7, 2015 @ 1:01 am

In terms of the dominance of the literati, that also explains why kana aren't used exclusively in Japan. In fact, it seems likely to me that Vietnam and Korea only switched over to entirely phonetic systems because a lengthy period of foreign colonization had left them without such a literati to defend the old systems.

Calvin said,

December 7, 2015 @ 2:05 am

I think the short-lived and controversial "Second Chinese Character Simplification Scheme") in China did incorporate some of these ideas, such as taking the cursive style (草書), simpler character to replace more complicated one, etc.

The first draft was introduced in 1977, but suspended less than a year later. The whole plan was abolished in 1986.

Matt said,

December 7, 2015 @ 6:03 am

What can we say about their principles of notation? Of course, it is obvious that they are willing to truncate terms radically.

虾饺 ⇨ 下交

I see what you did there…

In terms of the dominance of the literati, that also explains why kana aren't used exclusively in Japan

I'd say that the fact of having all those Chinese loanwords in the text was a more relevant factor. Note that you DO see a much higher proportion of kana in texts where Chinese loanwords were less prevalent (poetry, to an extent Genji-style monogatari, etc.), although this fact is obscured by the way modern editors tend to replace many of those kana with kanji to make the texts more readable for us moderns.

Anschel Schaffer-Cohen said,

December 7, 2015 @ 8:25 am

@Matt: I was talking about modern Japan, in the same period that simplified characters were adopted in Japan and China and phonetic systems in Korea and Vietnam. I'm not sure how much bearing the ancient texts have on that.

Kristina said,

December 7, 2015 @ 8:37 am

In response to the first comment think that prestige is a reason that kana might not have taken over in Japan, but given that there's no word boundaries in modern orthography and a number of homonyms, it is easier to read texts with some kanji (as opposed to all kana)–this is counter-intuitive to students in Japanese 1, but by Japanese 4 or 5, if you give them an old text with all kana running together, they have great difficulty "chunking" the words without kanji to help them out. And I do not think this is limited to or unique to foreign learners of Japanese: I think this is the reason that editors insert kanji into old kana-heavy texts.

This is not to say that certain aspects of kanji usage aren't maintained more by prestige or government fiat (for example, the need to use the correct kanji for tokeru—解ける or 溶ける—when referring to different situations of "to melt (snow)," which covered as a "problem point" in modern Japanese language according to NHK last year or the year before). "Incorrect" kanji usage is often blamed on technology (where you select the kanji after inputting the kana reading), but given the creativity of kanji usage on the internet, I'm unsure that Japanese will switch to all-syllabary usage under that pressure—at least not soon. Usage changes, yes (and more grumbling about how "young people don't use kanji correctly" from the mainstream media).

But if Japanese were to go the way of Korean or Vietnamese, I think you would also see word-spacing become standard as well.

David Marjanović said,

December 7, 2015 @ 2:30 pm

Yeah. That's what they want you to think.

maidhc said,

December 8, 2015 @ 12:31 am

Anschel Schaffer-Cohen: When Vietnamese was written in Chinese characters, they were used for their sound value only, not their meaning. So it was a phonetic system, but one with thousands of characters.

maidhc said,

December 8, 2015 @ 2:34 am

Anschel Schaffer-Cohen: So you're correct. Writing Vietnamese under the old system essentially required learning Chinese first, so only an elaborate court system could support the amount of study required to maintain a class of specialist literati. But hardly any ordinary people would have been literate.

When colonialism came in, the social system collapsed. The current alphabetic writing was devised by missionaries. They may not have been all that successful at converting people to Catholicism, but the writing system caught on, and today Vietnam has a very high literacy rate.

Eidolon said,

December 9, 2015 @ 12:56 pm

I think it also helped that the Japanese needed a way to represent their own native language words phonetically, and found kanji transcriptions a rather messy way of doing it – sort of the converse of what @Matt said. Just the same, I think the fact that there are so many different Sinitic dialects/languages in China contributed to the failure of phoneticization, as it'd have been rather difficult for people who had fundamentally different pronunciations for the various characters to come up with a consistent writing system based on their sounds. You'd have disagreements between officials from different regions over what basic syllable each character ought to stand for, and that's even ignoring the fact that, say, certain Cantonese syllables simply don't exist in Mandarin, and vice versa.

To this end, although the Chinese writing system is not ideographic, it did serve as a bridge between speakers of different Sinitic dialects/languages, who reached a compromise through learning Literary Chinese and memorizing characters' semantic values, all the while pronouncing them differently in speech. Chinese records speak of thick, unintelligible "accents" among provincial bureaucrats, for example, when they tried to address the government.

Such obstacles have not disappeared in the modern day. One cause for why pinyin hasn't become the official writing system of China, despite its practical benefits in electronic input and ease of learning, might well be because it's an alphabet designed for Mandarin, not other Sinitic languages, which require their own phoneticization schemes. To be sure, this issue may eventually go away as the other Sinitic languages lose their hold in the face of Mandarinization, but until that occurs, I think there's always going to be powerful political resistance in the PRC to using only phonetic scripts.

Jean-Michel said,

December 10, 2015 @ 3:55 am

I think the short-lived and controversial "Second Chinese Character Simplification Scheme") in China did incorporate some of these ideas, such as taking the cursive style (草書), simpler character to replace more complicated one, etc.

I was going to mention this–in fact some of the simplifications discussed here were ever-so-briefly "legitimized" as second-round simplifications, specifically 午 for 舞 and 亍 for 街. 疆 was also simplified, but not as 江; instead they just chopped off the left side and reduced it to 畺, which is supposedly an older character for the same word. Presumably 江 is used as an informal simplification because 畺 (with its 13 strokes) is still too complicated to serve as a useful shorthand.

Jean-Michel said,

December 10, 2015 @ 4:21 am

Correction to the above: According to Andrew West's detailed Unicode proposal on the second-round simplifications (among many others), only 午 for 舞 was actually official–亍 for 街 and 畺 for 疆 were part of an additional set of draft simplifications for possible future use.

Chas Belov said,

December 12, 2015 @ 5:55 pm

I see the comments to General Tso's chikin http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=4682 are closed so I'll post it here.

I too regularly see things like 反 for 飯. Actually, at a local Cal-Chinese place, I order brown rice and they just write 王 for 黃飯 (yellow rice); the restaurant moves fast, so the first time I saw it I assumed it was an abbreviation and not an error. I don't recall seeing 几 on a hand-written wall sign, and it's been so long since I ordered chicken at a Chinese restaurant that I don't remember whether I've seen it on a hand-written or computerized check, but I can't swear I've never seen 几 anywhere. I have regularly seen variations of 鸡 on wall signs of Cantonese restaurants.

As for General Tso's Chicken, I first noticed it at a long-gone Chinese restaurant in SF Chinatown called Dai Pai Dong. They had it on an untranslated chalkboard along with other dishes (odd now that I know its an American dish). I'm sure it was written as 左公[some chicken character variation] because I asked them what was "left public chicken"? They responded that it was actually "left male chicken." I asked them what if I wanted a right female chicken and they said I would be out of luck.

Eventually, a customer translated the chalkboard for them, and translated it as General Tso's Chicken or perhaps some variation; I don't remember. Then I started noticing the dish on other restaurant menus, likely an example of the recency illusion.