Is Q a Chinese Character?

« previous post | next post »

The title is from the subject line of a message sent to me a few days ago by Anne Henochowicz. Anne was puzzled by the expression ruǎn Q (軟Q) that occurs on a package of "Japanese style" cakes (mochi) made in Taiwan:

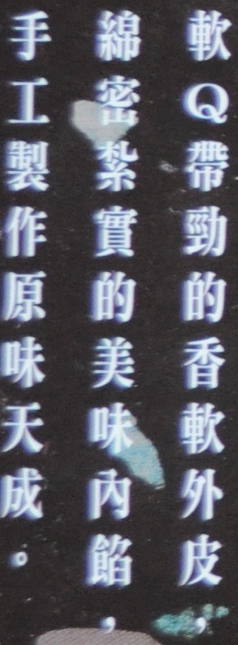

Here's a close-up of the relevant text:

The cakes are made by Royal Family (皇族).

I told Anne that ruǎn Q means "soft and chewy," where the Q (pronounced kiu) is a common Taiwanese morpheme that no one seems to know how to write in Chinese characters.

Another challenge posed by the package is that the characters used to write the Taiwanese equivalent of mochi, 米+麻 and 糬, are both exceedingly rare, neither of them appearing in Hanyu da zidian (Unabridged Dictionary of Chinese Characters; it has 54,678 entries) or other large dictionaries of Chinese characters. In fact, the first character is so infrequent that I have had to write it in the ad hoc fashion 米+麻. This extremely rare character is not even in Unicode (unless it has been added very recently), though it is probably a variant of mí or méi 糜[U+7CDC], with the "rice" radical at the bottom instead of on the side, while the second character is shǔ 糬[U+7CEC], which might be cognate with shǔ 薯 ("sweet potato"). Neither 米+麻 nor 糜, however, can compete in frequency with má 麻 ("hemp") for writing the first syllable of the Taiwanese rendition of mochi, since Googling yields 35 matches for "糜糬" versus over seven million for "麻糬." This is clearly one of the countless cases where the sound of a character trumps its meaning. In Japanese mochi would be written with the 餅 kanji, but in Modern Standard Mandarin (MSM) that would be pronounced bǐng and would mean "round flatcake."

To return to the problem of Q, however, here's a picture of a package of noodles with the brand name "Ah Q" (阿Q):

Taiwanese are particularly fond of prefixing the second syllable of a person's given name with "Ah" 阿 to express a feeling of closeness. For example, the former president of Taiwan, Chen Shui-bian was often referred to as Ah-bian. So I guess we could think of these "Ah Q" noodles as something like "Uncle Chewy" noodles, i.e., when prepared they are al dente.

This Taiwanese "Q" meaning "chewy" can be intensified by doubling, hence "QQ糖" ("chewy-chewy candy" or "really chewy candy"), nougats that are also styled "mini-Q."

Thus Q is clearly well established in Taiwanese as meaning "chewy," and it has been picked up on the Mainland with the same meaning (especially in advertisements). Since I've never been able to determine a cognate for this "Q" in other Sinitic languages than Taiwanese and no one has ever been able to tell me how to write this Q morpheme with a Chinese character, I have sometimes wondered whether it might not have come from English "chewy" itself.

Incidentally, these Ah Q noodles have nothing to do with the celebrated anti-hero, also called Ah Q, of Lu Xun's famous novella, "The True Story of Ah Q" 阿Q正傳 ("Ā Q Zhèngzhuàn"), first published serially between December 4, 1921 and February 12, 1922. "The True Story of Ah Q" is arguably the most influential work of modern Chinese fiction; it is generally considered to be the first work of fiction written in vernacular Chinese after the cultural revolution of the May Fourth Movement in 1919.

All Chinese know who Ah Q is, but no one knows for certain what the "Q" of his name means, much less how to write it in Chinese characters. The author begins the story by confessing that he himself does not know the origin of Ah Q's name, but there are various theories of where it came from, including that it might derive from "queue," the Manchu-imposed hairstyle which figures prominently in the story. Lu Xun tells us that the Q of Ah Q's name should be pronounced gui (as it would be romanized in Hanyu Pinyin).

Taiwanese informants tell me that Q can also mean "cute" (ditto for Cantonese). For instance, Q版 is a "cute edition" of a work; there are Xī yóu Q jì 西遊Q記 and Shǔihǔ Q zhuàn 水滸Q傳, which are "cute" cartoon editions of the famous early vernacular novels, Journey to the West and Water Margins.

A sentence such as nǐ hěn Q a! 你很Q啊 ("You're really cute") is thought to be a kind of clever semi-English, semi-Chinese hybrid.

Since the usages of Q as "chewy" and "cute" are both quite widespread in the Chinese-speaking world, one would need to be very careful about context when referring to a person as "Q" to make certain that one meant that they are "cute" and not "chewy"!

We have seen QQ as "chewy-chewy" or "really chewy" in Taiwanese, but it can also signify a type of instant messaging. This apparently is derived from ICQ ("I Seek You"; the name of an Israeli-American instant message service) and was originally called "Open ICQ (OICQ)," which was later absorbed into AOL. This service was developed by Tencent, Inc. of China and was launched in 1999. In 2000, AOL sued Tencent, which changed the name of OICQ to QQ, a usage that has since become very popular on the Mainland. One informant described QQ to me as "the Chinese equivalent of MSN" and opined that the name sounds very "cute."

QQ is so popular in China that there are a lot of things named after it. For example, Q bì Q幣 ("Q money") is a kind of special currency used by customers to buy extra service, and you can use Q as a verb, thus "Q wǒ ba!" Q 我吧 ("Contact me on QQ!"). QQ — with more than a hundred million users (as of March 5, 2010) — is the most popular instant message service in China, much more successful than Microsoft's Windows Messenger and Skype. Most users are young people, but many older folks also rely on it and would be familiar with the name.

Another usage for QQ on Mainland China is as the name for a mini car produced by Chery Automobile (Qirui 奇瑞), a Chinese company. To avoid confusion with the internet QQ, it is often referred to as Chery QQ (奇瑞QQ). Unveiled in 2003, Chery QQ was so successful that it became the best-selling mini-car in 2005-2007. It is often thought of as a car for ladies. Since it is the cheapest car in many foreign markets, including the EU, its sales have skyrocketed. (A photo of the Chery QQ is here.)

In addition, QQ is an emoticon for a pair of crying eyes. Another theory has it that this usage of QQ in the sense of feeling discomfited derives from the Internet game called Warcraft II, where one quits with the command ALT + QQ: "Why don't you QQ, noob?" Whether you play the game in Chinese or in English, you still have to QQ if you want to opt out.

There are still other uses of Q in China, among them in abbreviations borrowed from English, such as IQ, FAQ, BBQ, etc. Q on cards, the Queen, is not called Q in Chinese, at least not in Mandarin. In Mandarin it is called a quānr 圈儿 ("circle"), kuāng 筐 ("basket, container"), dàn 担 ("shoulder-pole [load]") (or dàn 蛋 ["egg"]?), or gēda 疙瘩 ("lump"), depending upon local variants. The Jack is called a gōur 鉤儿 ("hook"), or a dīngr 釘儿 ("nail"); the King is surprisingly often called a K (kèi or kài) or lǎo K 老K(“Old K"), and by some people bǎn 板 ("board").

In Cantonese, Q can apparently also have the meaning of "as luck would have it" or "uncanny" [kiu2, rising tone, probably the character 巧]. For example, if you run into someone randomly, you might say 咁Q既! = "It's so Q running into you!" But there is a much more frequent and more widespread usage of Q in written Cantonese, one which is very vulgar. Namely, one can say 好煩, which would mean "very bothersome," but if you insert a Q between 好 and 煩, hence 好Q煩, it means "fucking bothersome." Here are some examples with Cantonese romanization and English translation:

"你做乜嘢" [nei5 zou6 mat1 je5] “What are you doing?” =>

"你做乜Q嘢" [nei5 zou6 mat1 lan2 je5] "What the fuck are you doing?"

"你望乜嘢" [nei5 mong6 mat1 je5] “What are you looking at?” =>

"你望乜Q嘢" [nei5 mong6 mat1 lan2 je5] "What the fuck are you looking at?"

"你搵乜嘢" [nei5 wan2 mat1 je5] “What are you looking/searching for?” =>

"你搵乜Q嘢" [nei5 wan1 mat1 lan2 je5] “What the fuck are you looking/searching for?”

In these sentences, the Q is read as [lan2] ("vulgar morphosyllable for male sex organ"). Since lan2 does not sound at all like Q, the Q is not being used for phonetic purposes, but may perhaps be graphically suggestive.

For those who wish to know more about the function and meaning of “Q,” see pp. 14-15 of Robert S. Bauer's excellent The Representation of Cantonese with Chinese Characters, where it illustrates the 7th convention of written Cantonese. At the top of page 15, the lexical example with “Q” indicates that “Q” takes the place of some obscene morphosyllable, for example [lan2] "vulgar term for male sex organ," which functions as an intensifier just as expletives do in English; the reader knows to read/substitute [lan2] for Q in the sentence according to the context. Thus [lan2] can be translated as "fuck," "fucking," or "damn," as in the example cited above, maa4 lan2 faan4 Q煩 ("damn troublesome" or "fucking troublesome"). Page 51 of Bauer's volume reproduces a page from a Cantonese-language comic book in which a sentence with “Q” having the same function occurs.

Although Cantonese "Q" is a handy intensifier, it is considered to be so vulgar that many people substitute for it Chinese characters that sound roughly like "Q" (e.g., 鳩,鬼,巧). This is odd, since Q as a Cantonese vulgar intensifier is pronounced lan2, not anything that resembles the sound of the letter Q itself.

Enough on Chinese Q for now! Anne also asked about "AA," which is widely used in Chinese nowadays to mean "go Dutch." Since this post has already gone on long enough, and a minimally sufficient explanation of AA would require several paragraphs, that will have to wait for another time.

In closing, I'd like to attempt a brief answer to the question posed in the title, "Is Q a Chinese character?" Since Q is in common usage throughout the Sinophone world to represent several Sinitic morphemes, the argument might well be made that it is indeed a Sinogram (Chinese character).

It wouldn't be the first time that what was originally a foreign symbol became a Chinese character, e.g., 卍 (pronounced wàn = 萬 ["ten thousand"]), which was in use already from at least the early Tang period (618-907) with the meanings "auspicious" and "virtuous"; it is still used as a simplified character for wàn 萬 ("ten thousand"). Even earlier, during the Shang period, around 1200 BC, the character 巫 (MSM wū; "magus," but usually misrendered as "shaman") probably derived from the cross potent.

I would say that, whether Q may be considered a Chinese character or not, it certainly has become a part of the Chinese writing system. If anyone should try to outlaw Q from all Chinese writing, then there would be no way to talk about the most famous work of modern Chinese fiction or the best-selling Chinese mini-car, and one would not be able to describe the texture of mochi, gummy bears, and lots of other delectables, nor would one be able to ask one's friend to Q him on QQ, and you'd never be able to get out of Warcraft II.

[Thanks are due to Robert Bauer, Henning Kloeter, Tom Bishop, Richard Cook, Grace Wu, Gianni Wan, Sophie Wei, Wicky Tse, Genevieve Leung, and Lu Zhao.]

Wúmíng said,

April 15, 2010 @ 8:40 am

米+麻 is present in Unicode as U+2B0CE, and was added in the most recent version (5.2).

Dan Lufkin said,

April 15, 2010 @ 8:44 am

So Chinese needs a neologism for "chewy." Odd that all the Germanic languages (except English) get along without a word for "chewy." They all have words for "tough" and "sticky," which RHWCD gives as synonyms for "chewy," but they're not quite the same, are they?

Ben Whorf, call your office.

hanmeng said,

April 15, 2010 @ 9:21 am

I can only add that in northern China, 有劲儿 yǒujìr is used with a similar meaning to Q. "Chewy" is probably the best translation, but note that it's often applied to food that has a pleasantly chewy mouth feel. Try picturing an ad for "chewy" spaghetti!

Another thing–why doesn't anyone ever say "发Q"?

onaip said,

April 15, 2010 @ 10:10 am

It's not that Chinese needs a phrase for chewy,

很有嚼勁 means chewy alright.

Joe Wicentowski said,

April 15, 2010 @ 10:48 am

I think this calls for a new series of posts on the rest of the alphabet, A-Z. Or is Q unique?

Is Q a Chinese Character? « Mass Validation* said,

April 15, 2010 @ 12:26 pm

[…] This should be interesting. Here are some quotes: […]

Victor Mair said,

April 15, 2010 @ 12:48 pm

Joe, I probably could do the same for all the letters of the alphabet — would there were world enough and time!

Will Penman said,

April 15, 2010 @ 1:17 pm

Can't wait to hear about AA! When I was in China it was an expression that always puzzled me. And Chinese thought that it would be a familiar word for us, since it uses American letters.

Will said,

April 15, 2010 @ 1:34 pm

There's also '三Q', used online as a shortcut for 'thank you' (phonetic approximation of the English phrase).

Will said,

April 15, 2010 @ 1:43 pm

And of course, A菜.

Mark Mandel said,

April 15, 2010 @ 1:49 pm

This use of "ICQ" (the name of an Israeli-American instant message service) may be independently derived from the pun "I seek you", but I suspect they got it from the amateur radio call signal "CQ", used with approximately the same meaning since the beginning of the 20th century or before.

See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/CQ_%28call%29. I'd rather cite ARRL (the Amateur Radio Relay League), but they're remodeling their website.

Gene said,

April 15, 2010 @ 1:53 pm

Reminds me of the Cantonese cross-language pun Ho lan yut, "Holland moon," to describe something dull (like my lectures), because the English sounds like Cantonese hou lan mun "so fucking boring."

Lareina said,

April 15, 2010 @ 1:55 pm

haha i like letter Q

I m Q.

Ned Danison said,

April 15, 2010 @ 3:09 pm

Could this discussion be complete without the mention of "no Q" as a Taiwanese reply to the English "thank you"? Maybe.

CarrerCrytharis said,

April 15, 2010 @ 4:27 pm

Clearly he's British. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Q_%28James_Bond%29

TB said,

April 15, 2010 @ 5:16 pm

God this stuff is so fascinating.

Rubrick said,

April 15, 2010 @ 5:51 pm

My first thought on reading this was that the Sinitic world must have a thriving word-puzzle community. My second thought was that in the Sinitic world, "word-puzzler" and "speaker" might be synonymous.

Antonio said,

April 15, 2010 @ 6:09 pm

Hi there, I'm a Hong Kong Chinese.

Unfortunately the Cantonese sources seem to be a bit unreliable. Q, lan2 and gau1 are separate morphemes in our large swear word library for the male reproductive organ, and Q is an euphemism for the other two since it is perceived as less offensive. The use of it as an adjective/infix would be similar to British "bloody", or Australian "fucking", but not American "fucking".

Also, while Q in Cantonese could also mean cute, the chewy sense is absent in Cantonese.

kiu2 (for coincidence) and Q sound totally different. Q has tone1, so maybe the difference is like desert vs dessert.

The usual simplified character for ten-thousand is 万, not 卍.

pavel said,

April 15, 2010 @ 6:59 pm

I don't think "chewy" is the most apt way to describe "很Q" or "QQ"; perhaps "springy" or "al dente" would be better. For instance, I wouldn't use it to describe chewing gum.

Maybe there is no native sinograph for "Q" because in present-day Mandarin there are no other morphs with the same onset (k) and rime (iu) combination. The phonotactics are odd given the phonology of present-day Mandarin because the velars do not occur before the high front vowel (i) – I imagine the result of a historical process of lenition.

Tracy said,

April 15, 2010 @ 9:07 pm

I agree with Antonio for the use of Q in Cantonese. We do pronounce the "Q", e.g. "你做乜Q嘢" is pronounced "nei5 zou6 mat1 kiu1 je5", meaning

"What the hell are you doing?". So it's used both in speech and writing as a euphemism for the vulgar word for the male sex organ.

mondain said,

April 15, 2010 @ 9:20 pm

To understand the nuance between "Q-y" and "chewy", you may find this interesting

Zoe Tribur, “Q,” Gastronomica 6, no. 2 (2006): 47-48. http://caliber.ucpress.net/doi/abs/10.1525/gfc.2006.6.2.47

Tom said,

April 15, 2010 @ 10:57 pm

" it is generally considered to be the first work of fiction written in vernacular Chinese after the cultural revolution of the May Fourth Movement in 1919."

Diary of a Madman, 狂人日记, is widely considered the first vernacular Chinese work but was, of course published before the May 4th Movement. It also wasn't the first, but the genuinely first one (Miss Sophia's Diary) was a) published outside China and b) really dull, so Madman's Diary works out better all round.

Ah Q postdates 1919 but I don't know why it would be thought of as the 'first' baihua work after the May Fourth Movement. Lu Xun's own 明天 came before it but after May Fourth, for one.

Tom said,

April 15, 2010 @ 11:03 pm

Ah, I see Wikipedia has it as "the first piece of work fully to utilize Vernacular Chinese after the 1919 May 4th Movement in China".

Fully utilize? It seems an odd thing to say.

Anyway, back to the letter Q, at the end of the story, Ah Q has to write his own name but can't because he's illiterate. He ends up scrawling a pathetic kind of circle with a tail on it. The irony being of course that not only is this the Roman letter Q — so he's hit on his name by accident — but it's also sort of a cartoon drawing of his head.

Will mentions the "3Q" thing. It took me absolutely ages to cotton on to that one when I first encountered it, as I was mentally pronouncing it "three kew".

J.H. said,

April 15, 2010 @ 11:04 pm

Yes, I agree with Pavel. "Q" is more accurately described through the types of food that are "Q", like mochi, tapioca (like the kind in bubble tea), and maybe gummy bears. There isn't an English word for it, though I suppose (as Dan Lufkin said) we have it better than other Germanic languages. For this reason, I don't think the Ah Q noodles actually refer to the noodles being "Q", but are just a randomly chosen name.

jdmartinsen said,

April 15, 2010 @ 11:28 pm

Tom: …the genuinely first one (Miss Sophia's Diary)

That would be "One Day" (一日) by Sophia Chen Hengzhe. "Miss Sophia's Diary" was written by Ding Ling in 1927.

Charles Belov said,

April 16, 2010 @ 1:09 am

When I've watched HK movies subtitled in colloquial Cantonese, D turns up a lot.

@Ned Danison "Could this discussion be complete without the mention of "no Q" as a Taiwanese reply to the English "thank you"?"

That's cool. When Cantlish is appropriate, I've occasionally replied to "thank you" with "mh sái thank you." (Analogous to "dòh jeh" "mh sái dòh jeh;" "mh gòi" "mh sái mh gòi")

dòh jeh (thank you for a gift, applause, patronage)

mh gòi (thank you for a requested service, favor)

mh sái (not necessary)

Daan said,

April 16, 2010 @ 9:08 am

AA is certainly an interesting word. You can even say wǒ AAbuqǐ. The potential complement buqǐ means 'to be unable to afford', so this translates into 'being unable to afford (even) going Dutch'.

Fluxor said,

April 16, 2010 @ 10:04 am

I agree with Antonio. The use of 'Q' as an intensifier is no where near the vulgarity of 'fucking'. For those interested, the male organ 'lan2' is written in Chinese as a combination of 龍 and 門, much like the character 問, except the 龍 takes the place of 口.

onaip said,

April 16, 2010 @ 10:29 am

3Q is an imitation of sound of how the Japanese would say thank you. People heard it from JP dramas and would say it just to pretent to be Q.

Ho Sun Yan said,

April 16, 2010 @ 1:22 pm

Very interesting post, but, as others have indicated, the section on Cantonese is somewhat inaccurate:

1) Q is used as a euphemistic replacement for obscene words like lan2 and gau1, not just in writing, but also in speech (pronounced kiu1). If one were to read aloud a text that contains Q, one would pronounce it kiu1, not lan2.

2) The characters 鳩, 鬼, and 巧 do not sound roughly like Q and are not used to substitute for Q by virtue of being less vulgar. In fact the character 鳩 (gau1), as used in written Cantonese, is much more offensive than Q because it is used to directly represent the obscenity gau1 "prick". As for 鬼 (gwai2), it is very commonly used in colloquial Cantonese as a relatively inoffensive intensifier (e.g. 好鬼煩 "damn troublesome"); this usage has nothing to do with Q.

Tom said,

April 18, 2010 @ 9:44 pm

"That would be "One Day" (一日) by Sophia Chen Hengzhe. "Miss Sophia's Diary" was written by Ding Ling in 1927."

You're right! I *think* I can see how I got confused though…

Cecilie said,

April 19, 2010 @ 8:05 pm

No, intensifier "lan" is written with 能 inside the 門,not “龍”。

Can't wait to hear the origin of AA制 as no Chinese I've asked has had a clue.

Ho Sun Yan said,

April 20, 2010 @ 9:25 am

@Cecilie: Correct. The character 撚 is also commonly used to write this word.

Julen said,

April 21, 2010 @ 10:09 am

Actually ALL latin characters should be adopted as new characters into Chinese, they would just be phonetic symbols like 啊, 咦, 哈, 嗯. and anyway they are no more foreign than 她 or 万.

In a way, latin letters are already are accepted since pinyin is officially recognized. But they should accept them just openly to transcribe foreign sounds and proper nouns that it doesn't make sense to transcribe in characters.

A great example of why I say this: Has anyone noticed how the Chinese press translated the name of the volcano Eyjafjallajokull ??? LOL, don't even try to get that into characters. Most articles just avoided to name it and said: 冰岛火山 instead…

Bob Violence said,

April 21, 2010 @ 10:39 am

I asked this before (in the story about a guy named "赵C" who was forced to change his given name), but it was way too late and nobody saw it, so I'll try again: how are non-Han names registered in China? Are Tibetan names registered in Tibetan script, Uyghur names in Arabic script, Zhuang names in Latin script, etc.? Or are they legally registered under Hanzi transliterations?

bybell said,

April 24, 2010 @ 3:10 am

Phonetically, it seems Q would be yet another euphemism for diu2: http://www.cantonese.sheik.co.uk/dictionary/characters/1801/ rather than

dhd said,

April 26, 2010 @ 9:34 pm

I like the suggestion that Latin capital letters be adopted as phonetic symbols, since it means that they will become fair game for creating new semantic-phonetic compound characters.

Then, Unicode will have to be extended to include radicals as combining diacritics.

I actually learned about Taiwanese "QQ" from some friends talking about "白香果QQ綠茶" on Facebook, which is apparently the signature drink at a particular chain of tea shops (鮮百香果QQ綠茶), consisting of passionfruit juice and green tea with a variety of random chewy bits in place of the usual tapioca.

Chau H. Wu said,

June 11, 2010 @ 4:44 pm

Dear Victor:

Your suspicion that you "have sometimes wondered whether it might not have come from English "chewy" itself," is, in my opinion, almost on the mark. My hypothesis is that about 40% of Taiwanese words correspond to Germanic lexicon and 40% to Latin (+ Greek). Taiwanese khiū (kh- is aspirated k-; macron stands for the 7th tone in the Church Romanization script) has no cognate in Chinese, and as one commentator has written, Modern Chinese does not have such a sound anyway. To write it, the letter Q is borrowed. Old High German "kiuwan" (giving rise to New High German "kauen") and Old English "cēowan" have the meaning of 'chew'. Thus, the West Germanic *kew- may well have been the source of the loanword for the Taiwanese Q. Your intuition impresses me.

Some stuff – Frog in a Well China said,

September 26, 2010 @ 9:49 am

[…] Mair has a great post at Language log on the question of "Is Q a Chinese […]

Tezuk said,

November 4, 2010 @ 9:26 pm

Q actually has a Chinese character 臼 on top and 米 on the bottom (Taiwanese Education Department). However, I am not sure if this is a character they recently chose just to represent Q or if it was already an established character.

Taipei Part 1: Restaurants | More Than Eggs said,

August 12, 2011 @ 8:21 pm

[…] noodles here are always of a consistent quality, not too soggy and always Q – a Taiwanese term roughly meaning "chewy" – and the beef is just […]

RedQ firms as name for Qantas's new premium airline in Asia - FlyerTalk Forums said,

September 12, 2011 @ 8:31 pm

[…] an interesting link here on the potential meanings and use of the letter 'Q' in Chinese. http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=2252 at it's best Q can mean soft and […]

Theresa said,

May 15, 2012 @ 2:31 am

"Q" meaning chewy, when pronounced in Taiwanese, is the same as the Taiwanese word meaning "curly." Things that are curly have a springy, bouncy characteristic to them, much like the consistency of foods that are "Q." Or think of stir-frying squid…it starts out flat, and then curls up, at the same time obtaining a chewy, "Q" textures.

Theresa said,

May 15, 2012 @ 2:45 am

Have just looked over some of the comments. I agree with Pavel in that "chewy" is actually not the best English translation for the concept of "Q." A granola bar is chewy, but certainly not Q! Noodles are probably the most commonly commented upon food when it comes to Q (especially before the invention of bubble tea). That being said, I don't believe there is any linguistic tie between the Taiwanese word Q and any Proto-Indo-European language. From a cultural standpoint, there is a far stronger connection between something being Q as in curly, and a springy, bouncy texture that one means when describing a word as "Q."

Tasty Taiwan: Finding the flavours of my homeland in Berlin | ...then we take Berlin said,

July 22, 2013 @ 5:46 am

[…] another culinary obsession: chewiness. (Think gummy bears or a thick, al dente noodle.) For odd linguistic reasons, this food texture is called "QQ." The tapioca "bubbles" in bubble tea are […]

On “Q” | said,

November 27, 2013 @ 1:08 pm

[…] the roman alphabet,” so Jake dug around on the internet. Unsurprisingly Language Log has said something about it. And then there’s this, in […]

On “Q” | THE BITTERS said,

December 4, 2013 @ 5:11 pm

[…] the roman alphabet,” so Jake dug around on the internet. Unsurprisingly Language Log has said something about it. And then there’s this, in […]

Jessica Yang said,

May 28, 2014 @ 1:25 pm

Etymology for the 'springy' meaning of Q: 'Q' is the closest sound to a word in the Amoy dialect – possibly all equivalent words in the Minnan dialects of Chinese – that holds this meaning.