This delayed and dominating echo

« previous post | next post »

From reader GK:

One of your recent LL postings jogged an old memory. In the early 70s I sometimes hung out at Brown's college radio station, and one evening I was working on creating an ad in the production studio there. Somehow I managed (by accident) to set up the following situation: I was speaking into a microphone whose input fed into the record head of a reel-to-reel tape player, while listening to the output from the play head. I wore thickly padded earphones. The tape first passed the record head, then — after a fractional-second delay — the play head, so that I was hearing my own voice on that delay. Despite my best efforts, I could not utter an entire sentence, but would grind to a halt almost immediately. I wonder whether this effect has been observed in experiments (I would guess so). It's not surprising, of course, but I found it to be a powerful demonstration.

This effect is indeed well studied experimentally. It now goes by the name "delayed auditory feedback" (often abbreviated DAF).

The first documentation of DAF, as far as I know, was almost 60 years ago: Bernard Lee, "Some Effects of Side-Tone Delay", Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 22(5): 639, 1950:

I wish to call to the attention of those who have not yet observed it an interesting experiment in the field of psycho-acoustics which may be duplicated by anyone having access to a magnetic tape recorder with separate recording and playback heads, as for example, the Presto PT-900.

By plugging a telephone headset into the playback jac, a person's voice may be returned to his own ears but delayed by the length of time the tape requires to move from one magnet to the next. The effect of this delayed and dominating echo is startling — it will cause the person to stutter, slow down while raising his voice in pitch or volume, or stop completely.

(These days, you don't need a tape recorder — it's more convenient to use a computer program, e.g. this one.)

Back in the spring of 1950, Lee interpreted his observations in tune with the intellectual fashions of the times:

I believe that this phenomenon invites the application of fundamental concepts presented by Norbert Wiener in his book Cybernetics, since the elements necessary for Wiener's analogy between an electonic circuit oscillating with feedback and the means by which we govern many of our everyday physiological functions are strikingly manifest.

And he describes the effects in almost novelistic terms:

Of the subjects tested thus far, some develop a quavering slow speech of the type associated with cerebral palsy; others may halt, repeat syllables, raise their voice in pitch or volume, and reveal tension by reddening of the face. There seem to be different effects depending on whether the subject is reading, extemporizing, counting, reciting, speaking a foreign language, etc. Some have challenged the disturbance, but none have as yet defeated it. A prolonged session (more than two minutes) is physically tiring.

A couple of months later, he reported some quantitative experimental results, in Bernard S. Lee, "Effects of delayed speech feedback", Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 22(6): 824–826, 1950:

When a person's own voice is returned to his ears by technique of the multiheaded magnetic tape recorder and earphone a startling disturbance of his speech may be noted. A delay of about 1/4 sec. may cause the subject to speak very slowly but if he maintains normal speed, stuttering characterized by repetition of syllable or fricatives may occur. The level of the returned speech must be somewhat about that hard through bone conduction in order to be effective. This phenomenon seemed especially worthy of attention because of the important role played by the aural monitor of speech and because of the unudual opportunity afforded to experimentally hybridzie a neural and electronic network. A similar psychological upset of speech in certain auditoriums equipped with public address systems has been noted in the past.

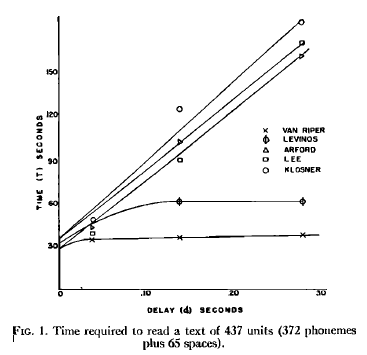

He measures the effects in terms of the time to read a short prose passage:

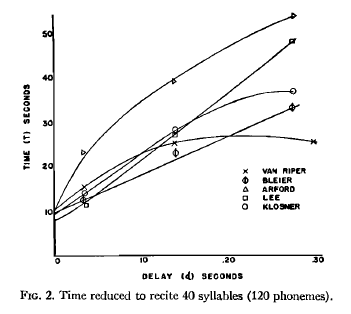

And similarly, the time to recite 40 syllables:

As you can see, there are considerable individual differences. (And quaintly, back in those pre-IRB days, he gives us the names of the subjects…)

Since 1950, there have been thousands of publications on related topics — see Aubrey Yates, "Delayed Auditory Feedback", Psychological Bulletin 60(3) 1963 for an indication of how extensively the topic had been investigated within a decade of Lee's discussions. One reason for the interest is the idea, present in Lee's first article, that this phenomenon may reveal something important about the process of speaking — and perhaps about the origins of some clinical disfluencies. Another reason is the paradoxical discovery that some people who stutter may become more fluent with moderate amounts of DAF (typically less than 100 msec) — see e.g. Peter Howell, "Effect of delayed auditory feedback and frequency-shifted feedback on speech control and some potentials for future development of prosthetic aids for stammering", Stammering Research 1(1): 31–46 (2004) for a review.

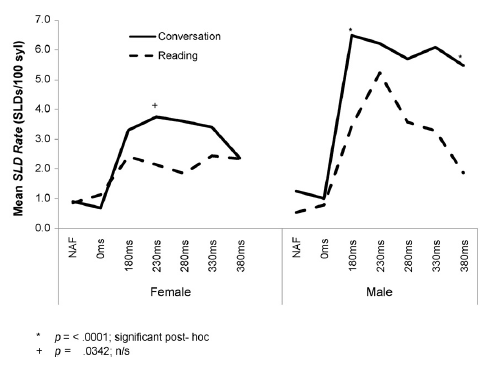

Another (somewhat random) observation that may be of interest to some is the significant (average) effect of speaker sex on response to DAF, as documented in David Corey and Vishnu Cuddapah, "Delayed auditory feedback effects during reading and conversation tasks: Gender differences in fluent adults", Journal of Fluency Disorders 33:291-305, 2008.

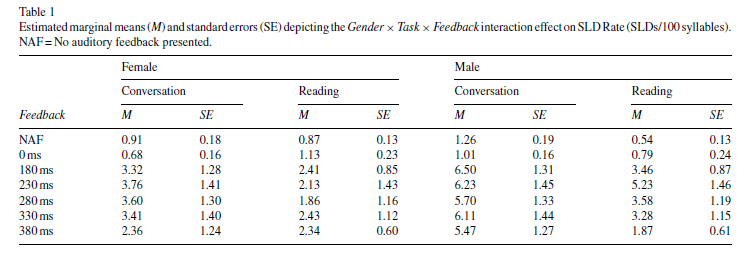

Here's their table showing the gender differences in "stuttering-like disfluencies" (SLDs) in conversation and in reading:

And the same information (at least the mean values) in graphical form:

You'll recall from Lee's 1950 paper that there are significant individual differences in response to DAF, within as well as across sexes, so I thought I'd try to calculate effects sizes (in terms of Cohen's d) for the data in table 1. In order to do that, I converted the standard errors to standard deviations, given that there were 20 male and 21 female subjects, and then divided the differences in the means by the pooled standard deviations. This is not really an appropriate measure, given 0 is the lowest possible count, and the performance distribution must have included a certain number of 0s, but we'd need all the original data to calculate more appropriate measures, like differences in quantiles.

| Conversation | Reading | |

| NAF | -0.42 | 0.56 |

| 0 | -0.46 | 0.32 |

| 180 ms | -0.54 | -0.27 |

| 230 ms | -0.38 | -0.47 |

| 280 ms | -0.35 | -0.32 |

| 330 ms | -0.42 | -0.17 |

| 280 ms | -0.55 | 0.17 |

(Negative numbers indicate fewer errors, on average, among female subjects. See e.g. here for a discussion of what an effect size of d=0.5 means — with the warning that this metric is hard to interpret when we're dealing with small positive-integer measures of performance… If the quantity under study were continuously variable, and not limited to positive integers, then an effect size of -0.5 in this case would lead us to expect that about 64 times out of 100, a randomly-selected trial involving a female subject would show fewer errors than a randomly-selected trial involving a male subject.)

As Corey et al. explain, these sex differences (among non-stutterers) are suggestive, given the large sex differences in the prevalence of stuttering:

Developmental stuttering (DS) is characterized by unintended speech dysfluencies. Specifically, people who stutter experience unintended repeated movements (repetitions of speech sounds) and fixed postures; the latter can take the form of prolonged speech sounds or prolonged silences during speech. Although DS has been widely studied, its etiology remains unknown. The condition begins spontaneously in about 4%of children, and about 75% of these recover spontaneously during childhood. The remaining 25% (1% of the population) continue to stutter throughout adulthood. The prevalence of DS is strongly linked to gender, both among those who recover from childhood stuttering and among those whose stuttering persists into adulthood, with males being more likely than females to experience DS and less likely than females to recover. As a result, the gender difference in DS prevalence increases with age, with the male-to-female ratio growing from about 2:1 in children to about 4:1 to 5:1 in adults. (See the paper for citations to back up these various quantitative and qualitative statements.)

There are lots of theories about where these differences come from; but that's enough for today.

Rubrick said,

February 14, 2010 @ 6:56 am

There's a booth demonstrating exactly this effect at San Francisco's Exploratorium. It's always been one of my favorites.

Ian Tindale said,

February 14, 2010 @ 8:36 am

In the mid-late ’70’s as a teenager I experimented a lot with pairs of reel to reel tape recorders and discovered this effect as I tried to lay down vocals while only being able to hear my own delayed voice. I was quite perturbed by the effect, which of course became a highly cool thing to play with — a lot. At the time, I likened the result, as I told all my friends, to: “it makes me sound American!”.

(I’m British, but this was during my first year living in Australia, and I was in the midst of picking up a Melbourne accent, which by the latter part of that year, my schoolfriends had difficulty believing I was ever anything but an Australian all along — of course within a year or so of returning to UK I lost it and became South-East British again).

I am reminded of a similar experiment I read about in electronics magazines of the day, where someone in a previous decade or so took a voice recording in standard RP English and slowly frequency modulated it with a sine wave, and it came out apparently sounding like a Welsh accent!

Brian said,

February 14, 2010 @ 8:55 am

Fans of They Might Be Giants will also be familiar with their song "Hide Away Folk Family", which has a spoken section in the middle in which John talks with an erratic rhythm, created by listening to a delayed feedback of himself while talking.

C Thornett said,

February 14, 2010 @ 10:19 am

Has anyone ever tried writing on a mis-aligned interactive whiteboard? This is also quite disconcerting. It is very difficult t write with any fluency or even legibility when the letters appear a short distance from the place you are writing.

[(myl) There's also a large literature on this subject, although I don't know much about it, and in particular I don't know whether anyone has studied the effect of displaced feedback of the type you cite (as opposed to prism glasses and the like).]

C Thornett said,

February 14, 2010 @ 11:27 am

My personal experience suggests that the conflict between kinesthetic and visual feedback is difficult to resolve, especially once the class starts to giggle.

Just one of the hazards of modern teaching.

rootlesscosmo said,

February 14, 2010 @ 11:42 am

DAF is experienced when playing certain types of pipe organ. On the one occasion when I (a pianist) tried this, the delay (I would estimate it at between 0.3 and 0.5 seconds) defeated me–I "ground to a halt" repeatedly and gave up. Organists, however, may constitute a distinct population whose members have learned to manage DAF as an inescapable condition of performance. Has this population been the subject of psycho-acoustic study? Are there others?

Ryan Denzer-King said,

February 14, 2010 @ 12:12 pm

I know that generally with audio recording equipment, latency of even 50-60ms is considered unacceptable. Even 20ms is perceptible, especially with a fast run on guitar or piano. However, there is a method used to prevent two copied tracks panned hard left and hard right from blending together, and that's to offest them between 5-15ms. In that range the delay is imperceptible, but it keeps the channels isolated left and right instead of blending to the center.

Bill Burns said,

February 14, 2010 @ 12:39 pm

A similar problem occurs when transatlantic and other intercontinental telephone calls are routed by satellite instead of by submarine cable.

Until 1956, when TAT-1 (TransAtlantic Telephone cable #1) was laid between Scotland and Newfoundland, phone calls between the USA and Europe were transmitted by shortwave radio, which had a very low propagation delay (or "latency"). TAT-1 replaced the shortwave circuits with 36 channels for phone calls, again with low latency.

In 1965 Early Bird was launched, the first geostationary satellite to provide communications across the Atlantic. Subsequently, satellites took over most of the telephone traffic, as they offered higher capacity than the copper cables of the time. But it was immediately noticed that callers had difficulty maintaining the smooth flow of conversation because of the round-trip latency of almost half a second, which removed the cues for when to start and stop speaking. (Synchronous orbit is ~22,000 miles; round trip distance is ~88,000 miles, or about half a second at the speed of light).

This was resolved when fiber optic cables were introduced in the 1980s. TAT-8, opened in 1988, was the first transatlantic fiber optic cable and provided 40,000 telephone channels with a latency of about 30 milliseconds. This took much of the voice traffic off satellites; each successive cable increased capacity exponentially, and today only a few percent of international communications travels by satellite.

The remaining source of high latency on voice communications is the satellite phone, often used by reporters in the field who do not have access to cable-based systems. It's very obvious when these are in use, as the studio anchor and field reporter will often stumble over each other's words.

Karen said,

February 14, 2010 @ 12:49 pm

I agree with C Thornett – that whiteboard thing is astonishingly difficult to deal with.

Matthew Kehrt said,

February 14, 2010 @ 1:23 pm

I find this happens on modern telephone networks from time to time. It makes communication nearly impossible.

peter said,

February 14, 2010 @ 2:07 pm

rootlesscosmo said (February 14, 2010 @ 11:42 am):

"DAF is experienced when playing certain types of pipe organ."

Organists who play with their backs to orchestras may be better than most of us in dealing with issues like this. At the opening ceremony of the 2000 Sydney Olympics, for example, the Sydney Symphony Orchestra performed at the Olympics site, together with an organist playing the grand organ in Sydney Town Hall, some miles away. They were connected by video and audio links, each with a noticeable delay. Despite the delays, they performed together well. To do this, the organist had to allow for both the delay in organ-sound audio transmission from him to the orchestra and the delay in conductor-image video transmission to him from the orchestra – ie, he had to play his notes just before they were required. But good orchestral musicians are usually able to successfully anticipate the intentions of conductors, particularly conductors they know well.

Mary Bull said,

February 14, 2010 @ 2:23 pm

Highly interesting comments as well as a fascinating article.

One other example of acoustic interference, which may fit into this discussion:

One of my sisters, whose level of absolute pitch discrimination is even higher than my own, cannot play on an out-of-tune piano music that she is otherwise able to perform perfectly.

Somehow I'm able to adjust and let my muscle-memory take over, in pieces I've memorized. But I can't sight-read music of any complexity on an out-of-tune instrument. The pitches I expect from reading the printed notation conflict with what comes to my ears to the point of exasperation.

Chris said,

February 14, 2010 @ 2:37 pm

Interesting to put this next to the phenomenon of Speech Shadowing. It seems like DAF has to do with hearing your own voice, not someone else's, or am I missing something?

Mary Bull said,

February 14, 2010 @ 3:43 pm

[QUOTE]Chris said,

February 14, 2010 @ 2:37 pm

Interesting to put this next to the phenomenon of Speech Shadowing. It seems like DAF has to do with hearing your own voice, not someone else's, or am I missing something?[/QUOTE]

Good point, Chris. But the discussion before my post had included comments on other types of auditory interference and how they affect performance — for purposes of comparison or contrast, perhaps?

Mary Bull said,

February 14, 2010 @ 3:57 pm

In regard to the use of the technology of DAF in connection with music performance, I found this piece of research referred to on-line:

http://www.tesionline.com/intl/thesis.jsp?idt=29153

Quoting the first sentence from the Abstract: "Research on music playing with delayed auditory feedback (DAF) shows that timing asynchronies between action and perception profoundly impair performance, to the extent that musical execution may be interrupted."

The point I was making in my anecdote above is that just anticipating hearing the sound one expects to emerge from one's actions can make the sound itself a kind of DAF and bring the musical execution to a halt.

[(myl) That would be "pitch-shifted auditory feedback" or "frequency-shifted auditory feedback", I guess, though the usual meaning is that the pitch of one's own voice is altered.]

Aviatrix said,

February 14, 2010 @ 5:41 pm

Sometimes the audio circuitry involved with a pilot's headphones, microphone and radio create this delayed effect, and it's fortunate that our required calls are generally very short, because even with formulaic transmissions the delayed echo can render us speechless within a few sentences.

codeman38 said,

February 14, 2010 @ 10:24 pm

There's a Morning Zoo-type radio show here in the southeastern US called John Boy & Billy. In one of their more famous moments, they had a retired police officer try to do a public service announcement live on the radio. Unfortunately, he heard the delayed feedback from the radio broadcast. Hilarity ensued, as he told listeners, in a half-unintelligible slur, to call nine-one-one-one in case of emergency.

(The clip is available as a paid download on iTunes, but for some reason, I can't find a streaming copy online. Go figure.)

John Walden said,

February 15, 2010 @ 8:17 am

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R-xhfy9cEAA

Both are hearing themselves speak a second later. It's hard to tell just how silly they are sounding unless you understand Spanish and because the programme is fairly silly to start with.

Ken D'Ambrosio said,

February 15, 2010 @ 9:01 am

There's one of these contraptions at the Boston Museum of Science. I always play with it when I go by — initially, it was very disconcerting, but, after a couple visits, I was able to train myself to ignore my feedback. Nevertheless, it appears I'm still dependent on feedback, because, while I can talk relatively quickly and with few errors, my speech is almost entirely devoid of inflection, intonation, etc. — akin to "robot speak," if you will.

Now I need to find me one of them mis-aligned whiteboards…

Nick Lamb said,

February 15, 2010 @ 9:35 am

The times given here are a bit difficult for humans to think about – we have a rough idea what a "second" is, but a millisecond dips below our conscious awareness. However, since we're dealing with sound there is a nice way to visualise this which also helps provide some parameters for what you could reasonably expect…

The speed of sound is a bit less than 350 metres per second. So, a millisecond is about 0.35 metres (say a foot for people who can't visualise metric units yet). When you're standing 35 metres from the orchestra at a concert, you're hearing the music 100 milliseconds after you see the instruments played (transit time for light is negligible). Is it noticeable?

Obviously you do normally hear yourself speak, about a millisecond or so after you do. This is somehow suppressed, and you don't "interrupt" yourself as happens with this delayed playback.

Dougal Stanton said,

February 15, 2010 @ 12:03 pm

Digital telephony equipment includes special compensation for the lack of sidetone, and if I remember correctly the Asterisk VOIP system allows it to be configured to some degree. I'm sure loud sidetone with long delay would be a most effective way of getting rid of annoying callers…

peter said,

February 15, 2010 @ 1:51 pm

Dougal Stanton said (February 15, 2010 @ 12:03 pm):

"I'm sure loud sidetone with long delay would be a most effective way of getting rid of annoying callers…"

The manual version of this works well: simply repeat everything said to you by a cold telesales caller, and they will usually hang up.

Kenny Easwaran said,

February 15, 2010 @ 9:57 pm

I had a phone at one point that would sometimes produce this effect. I found it very difficult to have a conversation longer than a few sentences without hanging up and calling again to see if the effect had gone away by establishing a better connection.

Stan Carey said,

February 20, 2010 @ 2:44 pm

Vienna's House of Music has an interactive booth demonstrating this effect. Maybe it's similar or identical to the one in San Francisco that Rubrick mentions above.

It prompts you to speak into a microphone attached to padded earphones, then delays transmission of the sound by a variable interval. There's a rolling pad to control the length of delay, but the computer suggests an exercise in which it asks the participant to delay the sound by a precise number of seconds, and then to begin counting and wait for things to get weird — which they do.

There are onscreen graphics representing what's going on between the user's mouth, ears and brain. I suspect that when you're in a confused state, colourful diagrams of your confusion can be pretty reassuring.

Michael Sappir said,

February 22, 2010 @ 2:48 pm

I wonder if any research has been done on this effect as passed through translation. To wit, when reading this post I was immediate reminded of a time about two years ago when I gave an informal talk in German which was being quietly simultaneously translated by a friend into English (my native language) for my Canadian then-girlfriend, the only one there who was not a German-speaker. Although the delay was probably always longer than a second and the feedback very faint, I had a profoundly hard time expressing myself calmly and coherently on the discourse level. I'm pretty sure producing full, coherent sentences was no more difficult than usual for that time, but it was hard to keep a train of thought going.

It would be interesting to see the differences in the effect when the feedback is in different languages, i.e. whether it is straightforwardly easier to talk the less one understands the feedback language (because the better you can understand, the harder it is to ignore), or perhaps the other way around (because processing a language you are still learning is often more difficult).

Aaron Davies said,

March 3, 2010 @ 8:38 pm

the cathedral of st john the divine in new york city has an organ with "trumpet" pipes over the front door, while the other pipes are all in the normal place at the back. as the nave is over 500 feet long, the organist must play those pipes at a significant delay to the others in order for the sound to arrive at the pews at the right time.

Darran Edmundson said,

March 27, 2010 @ 3:52 am

Any idea if the frustration DAF induces is similar to what is experienced by a stuttering person? I.e., Could experiencing DAF help people empathise with what it's like to suffer from stuttering?