Alexander of __?

« previous post | next post »

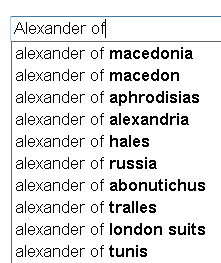

As the Google search suggestions on the right indicate, we generally view Alexander the Great as a Macedonian, and therefore, as the Wikipedia article about him says, a "Greek king".

As the Google search suggestions on the right indicate, we generally view Alexander the Great as a Macedonian, and therefore, as the Wikipedia article about him says, a "Greek king".

But according to one of the many contrarian nuggets in Jim O'Donnell's The Ruin of the Roman Empire, this is the wrong way to look at it.

His take:

Alexander the Great, a right-minded man even if he did drink too much (according to the common view), sought to conquer all of Persia and succeeded, but he died too soon, and his conquests were lost. Few people spend much time imagining a middle-aged and successful Alexander, a man lucky enough to live as long as Augustus did, let's say. If we knew that man, we would know him not as a Greek or Macedonian, but as a Persian emperor. That is what he set out to become, and that is how he appeared in much of the territory he crossed. At his death, his armies were turning rapidly Persian in composition and form, and they would have become much more so with the passage of only a little time.

Just as the language of the (Eastern) Roman Empire was Greek for a millennium or so, perhaps if Alexander had lived, there might have been a "Greek" empire whose language was Persian.

Jim continues:

His conquest would have proved what only the Ottomans ever demonstrated–that linking the Aegean basin with Asia Minor and Mesopotamia was possible and, if achieved, could have been a source of great power for the one who accomplished the bravura deed. For Alexander to be Macedonian, from the farthest reaches of territory within Persian ken, was no disqualification: conquering rulers in many societies come from the margins, at least as often as from the center.

Alexander's Persian empire collapsed after his death and fell into pieces. The Seleucid kings who prevailed in the Asian provinces of Alexander's empire, notional partners to the successor kings who took the name Ptolemy in Egypt and the similar Antigonids in the Aegean basin, proved unable to maintain even the traditional Persian pretensions and range, from Syria to Afghanistan, and were for centuries a limited and dwindling force on the world stage. The Seleucids prevailed for scarcely a century before beginning to give way to the Parthians, based in the Iranian uplands, who went on to dominate central Asia until the third century CE. Landlocked, turned in on itself, never seriously expansive in the west, this Parthia was a great success story in its own right, but the central fact of its existence was its geographic focus, far from the Mediterranean. And that is why the Roman empire could exist. It had no serious Persia to deal with.

Q. Pheevr said,

October 31, 2009 @ 8:59 am

Alas, things did not go well for the would-be Persian emperor:

"I left the battle with blood in my helmet and now there's blood in my hair and when I got out of my armor this afternoon I tripped on a dead solder and by mistake I dropped my sword in the catapult while the thing was launching and I could tell it was going to be a terrible, horrible, no good very bad day. "

Innokenti said,

October 31, 2009 @ 9:40 am

Taking a peek in Blackwells today, I glanced on the very same 'The Ruin of the Roman Empire' and was quite intrigued. It is probably one to read, but based on the extract you have provided and the first page I read, I am far from convinced. Having studied all these things myself O'Donnell's summary seems a little… pithy and while he obviously has a point regarding the ambiguity with which we might view Alexander and his position, most of his other assertions are more about effect rather than substance.

It would be wrong to see Alexander as just a Greek or Macedonia or Persian – in some ways he was all and none of those.

O'Donnell isn't particularly wrong, but I don't think his summary, leading as it appears to a point to be made regarding the Roman Empire, does justice to how we might look at Alexander and his Successors.

I really ought to read the book.

[(myl) Yes, you should. The stuff about Alexander is really just a point in passing, serving as an illustration of our more general tendency to think of "east" and "west" in terms that (O'Donnell thinks) make it harder for us to see what forces and what opportunities really confronted Justinian in the 6th century. O'Donnell's main thesis is that Justinian "[kicked] away his opportunities and [left] his successors with few choices except to muddle and manage in the world he had ruined."]

Anonymous Coward said,

October 31, 2009 @ 10:05 am

So what O' Donnel is saying is that when the British conquered India, they became Indian? I think it usually works the other way around.

[(myl) I believe that the usual spelling is "O'Donnell", with two l's. And other conquests to consider would be the Normans in England, or the Mongols in China and later in central and south Asia, or the Vikings in Russia, or …]

Jason Cullen said,

October 31, 2009 @ 11:09 am

I think the Manchus in China is a better example than the Mongols.

[(myl) There's also Attila the Hun, whose name means "little father" in Gothic, and whose army was apparently largely Germanic by the time he reached Europe.]

Jim Parish said,

October 31, 2009 @ 11:13 am

Fletcher Pratt made a similar comment as regards the Hundred Years War in his The Battles That Changed History, Chapter 6: "Jeanne d'Arc and the Non-Conquest of England". (His contention was that English victory in the war would have led to the absorption of England into France, not the converse.)

Jongseong Park said,

October 31, 2009 @ 12:00 pm

I think the Manchus in China is a better example than the Mongols.

The Manchus ruled China for roughly three centuries while the Mongol rule of China lasted a century or so. Consequently, it's easier to think of the Qing Dynasty as Chinese and forget that the rulers were Manchus, while we have a harder time separating the Yuan Dynasty from the Eurasia-wide phenomenon that was the Mongol Empire.

Adding in Alexander's example, it seems to indicate that the longer-lasting an empire (or similar political entity), the weaker the popular association to the original rulers and the more likely we are to consider its identity based on its dominant culture (plus the ruling class tends to assimilate to the dominant culture over time, anyway).

Craig Russell said,

October 31, 2009 @ 1:19 pm

Interesting how sometimes a conqueror or conquering force imposes their own language and sometimes they absorb the language of the conquered. Whether Alexander was becoming more Persian or not, the fact is he and his successors DID impose the Greek language on many of the lands they conquered, which is why the eastern Roman empire spoke Greek. And the evidence of the Romans spreading Latin throughout Western Europe is still apparent from the languages of those ex-Roman provinces (except, for the most part, England, of course). But then there are all of MYLs counter-examples–what makes the difference?

Still–although Alexander is far from my area of specialty–I think the question of knowing anything about him is kind of tricky because of the nature of the evidence. In my understanding, none of the contemporary sources describing his life survive; all we have is second or third generation re-tellings, by which time he was already a larger-than-life legend. Could it be that accounts describing Alexander's 'Medizing', were at the least influenced by the literary pattern that had been established over the past century or so (plenty of examples in Herodotus and Thucydides–Themistocles springs to mind immediately) of Greeks who fell into the Persian sphere of influence, started taking on the material trappings of the Persians, and, in so doing, lost their Greekness? It seems like there was already anxiety about authenticity of the Greekness of the Macedonians in the first place (examples, I think, in 4th century Athenian oratory). Maybe these kinds of stories about Alexander could be seen as an extension of these themes: the questionable Greekness of Macedonians plus the tendency of Persia to strip away the Greekness of Greeks.

Again, this is just me speculating, because it's not an area of Greek history I've studied extensively. I could easily be proved wrong; I'm just thinking out loud.

Picky said,

October 31, 2009 @ 2:00 pm

@Jim Parish: And perhaps a British victory in the War of Independence would have ended with the British Empire run from what was left of the White House? There's a thought.

peter said,

October 31, 2009 @ 3:49 pm

"Interesting how sometimes a conqueror or conquering force imposes their own language and sometimes they absorb the language of the conquered."

This issue has always intrigued me. The Normans (who were originally Vikings) under William the Conquerer used French at Court after their invasion of England, and French words gradually entered English. Why, then, did Dutch not have similar influence on English after the Dutch invasion of England under William of Orange in 1688?

Jonathan said,

October 31, 2009 @ 3:53 pm

The peculiarity of the Macedonians was that while their royal house was considered Hellenic (so that, for instance, they were invited to participate in the pan-Hellenic games at Olympia and elsewhere), the rest of their people, including the nobility, were considered barbarian. Alexander was of the royal house, so there's no question the rest of the Greeks saw him as a Hellene. Yet the subjugation of the Greek polities by his father Philip could still be seen as barbarian conquest (hence the anti-Philippic oratory of the Athenian Demosthenes that Craig Russell mentioned). And this was well before Alexander began his campaign of conquering Asia and further 'barbarizing' Hellenic civilization.

Jonathan said,

October 31, 2009 @ 4:08 pm

@peter:

It's actually a widespread misunderstanding that the influx of French vocabulary into English was due directly to Norman conquest and settlement. Norman settlement was in fact limited to the aristocracy, and it only took about a generation after the conquest before bilingualism in English and Norman French began to appear even among them. Post-conquest English literature remains largely Anglo-Saxon for quite some time after the conquest: in fact, the most considerable evidence of new foreign influence in 12th and 13th century English is not French, but Scandinavian, even though the Danish conquest took place centuries before! But that's another story.

SIgnificant French influence begins to be seen in the late 13th century and on, long after the Norman conquest. The reason is the accession of the Plantagenet dynasty, which extended English contact with France both in time and place: whereas the limited French influence before then was entirely Norman, afterward we see the main source in Middle Parisian French, a very different dialect. Examples are Norman 'gaol' versus Parisian 'jail'. As one might expect, the French influence correlates strongly with the rise of a courtly English dialect (Chaucer etc), which borrowed not only French literary styles and forms but also vocabulary. The language of Parliament remained Norman until the end of the 14th century, by which time the English aristocracy had largely abandoned it as an everyday language.

Since the accession of William and Mary in 1688 was not accompanied by any significant Dutch settlement, it's not surprising there would be very little Dutch influence. Indeed, such influence is apparent, especially in nautical vocabulary, where contact with the Dutch was strongest.

J. W. Brewer said,

October 31, 2009 @ 5:58 pm

I started this book last spring but lost steam before getting into the boo-Justinian section. Leaving aside other problems with the speculation, a Persian-speaking "Greek" empire seems improbable since the Persian Empire Alexander conquered was not itself particularly Persian-speaking outside modern-day Iran, but instead is said to have used Aramaic (the variety sometimes called "Imperial Aramaic") as its administrative language / lingua franca. (This is one of the case studies in Ostler's book, showing that the way in which a language's success correlates with the political/military success of a particular language community is more varied than sometimes supposed.) In Syria and its environs, Greek and Aramaic were still competing with one another almost a millenium after Alexander when Arabic entered the picture rather suddenly and forcefully.

Indeed, if Persification had been in the cards linguistically, one would have expected to see it in the Seleucid Empire since it started with all the Persian-speaking territory Alexander took but less of the non-Persian-speaking territory, but that doesn't seem to have happened.

J. W. Brewer said,

October 31, 2009 @ 6:22 pm

Oh, and pace Demosthenes, modern Greek ethnolinguistic nationalists mostly seem to treat Alexander and the Macedonians in general as not only Hellenized but 100% echt-Greek, as can be seen by their tragicomic attitudes toward their Slavic-speaking contemporary Macedonian neighbors to their north. I don't have as much experience with modern Chinese ethnolinguistic nationalists, but my vague impression is that they do not embrace the Mongol and Manchu conquerors (however much they got Sinified in the course of time) quite so unreservedly.

Jonathan said,

October 31, 2009 @ 6:58 pm

@ J. W. Brewer:

Modern Greek nationalism does indeed simplify the ancient issue of whether Macedonia is truly part of Hellas or not. However, as I said before, the Macedonian royalty was considered Hellenic, so an ancient connection between Macedonia and the rest of Greece is indisputable. Of course, these concerns of modern Greek nationalism tend to ignore the considerable intervening history of Roman and Ottoman rule. The nationalists mainly object to the use of the _name_ 'Macedonia' for the independent Slavic-speaking country; the territorial claims also exist but invoke less concern among Greeks. If it is somewhat ridiculous for Greece to lay territorial claims to independent Macedonia based on such ancient and long-defunct connections (from a time when there was no unified Greek state in any case), it is just as ridiculous for the Slavs who now occupy the region to consider themselves in any way heirs to ancient Macedon, since they didn't turn up until the sixth century at the earliest.

Acilius said,

October 31, 2009 @ 7:19 pm

"perhaps if Alexander had lived, there might have been a "Greek" empire whose language was Persian." If Alexander had lived into his 70s, I'm sure his empire would not have collapsed after his death. It would have collapsed long before his death. Were the Macedonian king alive, Macedonian generals such as Ptolemy and Seleucus would have had to frame their scramble to seize what they could of the territory he had conquered as a revolt against that king. The consequence of that revolt would doubtless have been quite different from the consequence of a struggle that was presented as an attempt to continue Alexander's work. Indeed, all trace of Alexander's conquests might have vanished had he lived long enough to become an embarrassment to his countrymen.

mollymooly said,

October 31, 2009 @ 9:18 pm

other conquests to consider would be the Normans in England…

…and then the Anglo-Normans in Ireland: Hiberniores Hibernis ipsis

John Cowan said,

October 31, 2009 @ 11:57 pm

Craig Russell: Military conquest by itself never, or almost never, causes the imposition of the conqueror's language. About the only exception is the English conquest of Britain. Languages spread mostly through cultural, commercial, religious, or similarly subtle forms of imperialism: it is assumed rather than imposed. The same is true of the spread of Greek, which was going on before Alexander's day and continued much longer.

Jonathan: Names are but names.

Acilius: With a clear Greek-Persian heir (Stateira's child), I'm far from sure that the empire would have collapsed. After Alexander's death, there was a power vacuum, exacerbated by the question of whether his dying words left his throne to Krateros (one of his generals) or kratistos (the strongest).

Peter T said,

November 1, 2009 @ 1:01 am

Interesting point about India and the British – they did become Indian (or at least the small number who went to India), and lots of Indian words entered English. But I understand borrowings from Irish into English are very rare. It may have something to do with the form of conquest – the British in India were in a partnership with the Indians – albeit as senior partners, but the English never had much interest in anything more than exploiting the Irish. Alexander seems to have had in mind a Greek-Persian partnership, sensibly recognising that running anything east of the Euphrates in opposition to the Persians was not on, so maybe some form of Greek-Persian creole would have emerged, along the lines of Urdu.

Picky said,

November 1, 2009 @ 5:17 am

Whatever date you might choose for the English/Scots/British conquest of Ireland I think you'd find English being already spoken on that island: the warring/trading/settling relationships between the people of these islands goes back thousands of years, so things are much more complicated than with the expansion of British India. Of course in Ireland the native language was deliberately suppressed by the British, whereas the same was not true in India.

Meanwhile, haven't we left out the British-American-Canadian conquest of North America? That seems to have been linguistically a bit of a wipe-out of native tongues, hasn't it?

judith weingarten said,

November 1, 2009 @ 6:21 am

One good reason that the Dutch did not impose their language on the English is that the Dutch court spoke French, rarely Dutch Another reason is probably the King James bible (1611) which made a fixed reference for the language throughout the realm; otherwise, we'd probably have the same trouble reading Shakespeare as we do Chaucer.

@John Cowan. I'm a little surprised that "Military conquest by itself never, or almost never, causes the imposition of the conqueror's language." Did Caesar never come, see, conquer Gaul?

Picky said,

November 1, 2009 @ 8:08 am

@John Cowan: I don't like to be too pi about this, but since relations between the English and the Scots have become more sensitive again perhaps I can question the concept of an "English conquest of Britain". The union of those two nations, at any rate, was brought about by (a) the passing of the English crown to the Scottish royal house and (b) an act of the two parliaments. Of course politics was even grubbier in those days, but it was certainly not a conquest by force of arms.

Aaron Davies said,

November 1, 2009 @ 8:20 am

I think the Japanese made a good try at imposing their language on China, didn't they? And of course, @Picky, the same is true, if not with quite the same thoroughness, of the Spanish and Portuguese conquest of Mexico and points south.

Aaron Davies said,

November 1, 2009 @ 8:24 am

@Picky: I assumed he meant the one that took place c. A.D. 500, not 1567 (or 1997 :).

Picky said,

November 1, 2009 @ 11:51 am

Ah, you think John meant Britannia?

marie-lucie said,

November 1, 2009 @ 1:40 pm

"Military conquest by itself never, or almost never, causes the imposition of the conqueror's language." Did Caesar never come, see, conquer Gaul?

The conquest of Gaul and other countries meant the imposition of Roman rule and administration, and the Celtic-speaking Gauls eventually (after several centuries in some cases) switched to a form of Latin. Later, the Romans conquered most of Britain and occupied it for four centuries, but there is no evidence that the Celtic-speaking population switched to Latin in significant numbers. In the case of Gaul, before Caesar's conquest there was already a lot interaction with the Roman world through trade, so quite a few Gauls knew some Latin, at least in the cities and along major trade routes. Also, the Romans encouraged conquered populations to join the administration. As with the British system in India, no one was forced to learn the dominant language, but knowledge of it was highly beneficial for social advancement, or, for the elites, a necessity in order to have a say in the new administration. After the fall of the Empire, by which time most of Gaul spoke a form of Latin, the Church as the only remaining administrative structure kept up the prestige and the international utility of the language, and the Germanic conquerors adopted it as well, eventually merging with the local population. Modern examples of imposition of a language involve schooling large numbers of children in the dominant language, which they end up knowing better than their own, and later raising their own children in it. In earlier times, many sons of the upper class were sent to a different country (or to schools where they existed) in order to learn a more prestigious language, but this did not immediately affect the bulk of the population.

"the Dutch conquest of England"

There was no "conquest" equivalent to the Norman conquest. There is a parallel in the fact that both Williams were relatives of the reigning family at the time of a power vacuum caused by the lack of an obvious heir. But William of Orange was invited by one of the English factions to sit on the throne, and his show of force was minimal. Nor was the country taken over by a Dutch administration and colonists, or Dutch schools set up to instruct English children in the Dutch language. Similarly, when George of Hanover became king of England, this did not entail a "German conquest of England". With all the reigning European families entertwined through marriage, the peaceful importation of a foreign-born relative was by far preferable to the upheavals which might be caused by the rise of a local upstart.

Irene said,

November 1, 2009 @ 3:22 pm

"The peculiarity of the Macedonians was that while their royal house was considered Hellenic (so that, for instance, they were invited to participate in the pan-Hellenic games at Olympia and elsewhere), the rest of their people, including the nobility, were considered barbarian"

@Jonathan,

More or less i agree with your input but i keep some doubts about the latter. While ancient sources frequently tend to seperate the Macedonian people from the Southern Greeks, as a rule they also tend to seperate them from the Barbarians. I guess noone can point out the reason with certainty. I will take a shot and make an assumption. Perhaps Southern Greeks were aware of a mixed Hellenic-Barbarian population residing in Macedonia, hence Macedonian people were viewed as semi-barbarians. Especially Thucydides is explicit that native barbarian populations were incorporated in the Argead kingdom and became Macedonians. If the population was entirely barbarian, this would be evident in their names/toponymics. This does not happen and furthermore, contrary to the neighbouring people ie Illyrians and Thracians, the Macedonians had in their majority, names with Greek etymology. I have to add that even at the time of Strabo we have some conflicting accounts. Strabo states from one hand that "Macedonian is a part of Greece" and on the other hand, he also mentions that "certain parts are held by Barbarians".

David Smith said,

November 1, 2009 @ 7:05 pm

"conquering rulers in many societies come from the margins, at least as often as from the center."

I recently read something about Napoleon, Hitler and Stalin all being examples of this phenomenon, but I'd like to see a more rigorous analysis . . . does anyone know of anything?

Acilius said,

November 1, 2009 @ 7:20 pm

@John Cowan: In branding ice cream shops and software packages, names may be but names. In politics, neither a name nor any other thing is ever only itself. Everything comes trailing everything else. It's all attached someplace, every relationship, every grievance, every plan, every fear, every hope, every hurt ever suffered, every joy ever cherished.

As for what might have happened had Alexander lived as long as Augustus, I don't dismiss the idea that a well-placed, dynamic individual can, under the right circumstances, sometimes change the course of history. If this idea seems implausible to twenty-first century inhabitants of the developed world, it is likely because it has been our fate to spend our lives in a societies dominated by impersonal bureaucratic institutions of a sort unknown in other epochs.

But neither do I see the slightest grounds for believing that an Alexander granted Augustus' longevity would have shown Augustus' capacity for long-term planning and coalition building. Alexander's strong personal tendency to violence (killing by his own hand such members of his inner circle as Cleitus, for example) suggests very poor impulse control, hardly surprising in view of the many wounds, likely including many head wounds, he suffered in battle. Compare Alexander's response to Philotas' conspiracy with Augustus' celebrated clemency towards figures ranging from defeated rivals like the triumvir Lepidus to suspected coup plotters like Maecenas. We must expect that an impetuous, bloodthirsty captain like Alexander, asked to govern an empire in peacetime, would have committed one rash misstep after another and proven a very heavy burden for his empire to bear.

Moreover, while the Persian Empire and the Greek west were hardly worlds apart in Alexander's time, neither were the links of trade and communication between those regions anything like as intricate as they would be in the time of Trajan and Hadrian. And even Trajan and Hadrian, seasoned administrators and broadly sane as they may have been, could not keep such a behemoth united for more than a handful of years.

That's why I do appeal to a sort of "great man theory" regarding Alexander's death. In death, Alexander could be a majestic symbol of the possibility of a world united. The Hellenizing cultural practices of the successor states could be interpreted as a tribute to that possibility, and as such could continue indefinitely. Had he lived, Alexander would either have continued as he had begun with his erratic, violent ways, in which case he would have smashed his empire to atoms in a few years; or, he might have defied probability and recovered some sort of mental balance, struggling at the impossible task of building a ruling elite capable of holding his empire together, and when he failed taking Hellenism down with him.

judith weingarten said,

November 2, 2009 @ 3:05 am

Hi Marie-Lucie,

Of course there was pre-Caesar contact and trade between Italy and Gaul; in fact, it goes back as far as the Etruscans. Except for the conquest of the New World, that is almost always the case. And, needless to say, it took centuries for most of Gaul to switch to a Latin-based language. The point is that it was a *military conquest* that led to the change of language.

By the time the empire fell, I doubt that the language of the Church was the same as that spoken by the people, not even by the Romanized elites (some of whom would probably have spoken a pure Latin as well as did the higher clergy). The languages would, I think, have already diverged, so what the Church preserved was more Latin than early French. Anyway, what is interesting is that the incoming Germanic conquerors did not radically change the language again. I wonder why.

plegmund said,

November 2, 2009 @ 7:23 am

Actually I think towards the end of his life Alexander was 'set on' becoming an Indian emperor.

marie-lucie said,

November 2, 2009 @ 10:31 am

Judith, I agree in principle with everything you say. But in the case of Gaul (and Spain earlier) it seems that "military conquest" did not remain just "military" but was followed by administrative conquest and co-opting of elites, and had been preceded by a fair amount of cultural conquest. This does not have to be the case: many military conquests have ended either in the withdrawal of the conquerors (as with the Romans in Britain) or in their absorption by the local population (as with the Vikings – both Danes and Normans – in England). Also, the fact that the Church (or the higher echelons) preserved (in writing) a relatively more classical Latin than that spoken by the masses is irrelevant to the fact that the Germanic conquerors (and settlers) did not preserve their own language but eventually switched to that of the local population. In the case of Gaul, a common administration put an end to local wars and the building of roads and other infrastructure allowed trade and mobility throughout the country and beyond. Knowledge of Latin, and ability to write it, vastly expanded the range of experience available to the Gauls. The Germanic invasions put an end to most of this, but the aims of the new conquerors were not to destroy but to take over Roman culture. Writing was not extended to their own, unprestigious languages at that time but continued to be in Latin and a near monopoly of the Church, an international cultural and administrative force. Knowledge of Latin therefore continued to have high prestige as well as utility, and here the locals were seen to have an advantage over the conquerors. Three centuries after the establishment of Frankish rule in what was now France, Charlemagne had to be told that the population no longer spoke true Latin, and set up a school in order to teach it. But the Germanic conquerors did have an influence on the local language: as usual there must have been a degree of bilingualism, and many of the phonetic changes which make French so different from Spanish, Occitan and Italian are attributed to Germanic influence. The Franks must have spoken the local varieties of (very late) Latin with a strong accent, and in time the locals must have imitated the pronunciation of their overlords.

Cameron said,

November 2, 2009 @ 10:43 am

The idea that Alexander's empire would have been Persian-speaking had he lived longer seems strange to me. The Persian empire was a huge polyglot expanse, and at no time in the Achaemenid period was Persian ever its administrative language. The scribes at the Persian court mostly used Elamite – and there is every reason to believe that Elamite was the lingua franca of the imperial bureaucracy. The Seleucid empire and the Parthian empires (the latter of which lasted for centuries) both used Greek as their administrative lingua francas.

Sparadokos said,

November 2, 2009 @ 2:22 pm

There are good reasons to suspect that, while the Macedonian elites were hellenized, the masses were not, and spoke a divergent dialect of Greek or even a sister-language.

There is the well-known incident in Arian when Alexander, in a moment of danger, called out to his Companions "in Macedonian."

A better example is the feminine name Berenike, "bearer of victory", which in Greek would be Ferenike. A similar example would be danos, "death", which in Greek is thanatos. That these stops are devoiced in Greek is one of the defining characteristics of the Greek language. So if we are going to classify Macedonians as purely Hellenic, we will need to revise our defintion of Hellenic, at least linguistically.

My view is that the Macedonians were part of a sister-group to the Hellenes (perhaps including the Phrygians), who were distinct at the time of the Trojan War (notice M.'s are not players in the War nor are even mentioned). As Greece emerged out of their dark ages, the elites of Macedonia increasingly asserted their Greek-ness, and by the time of Phillip and Alexander they were culturally Greek.

On the fact of Macedonians participating in the Olympic games. Herodotus puts forward this claim, but in fact their names do not appear in the lists of participants which have come down to us.

John Cowan said,

November 2, 2009 @ 5:26 pm

Picky: What happened in North America was not so much military conquest as involuntary genocide resulting from the superior parasites of the invaders. There has been speculation that something happened in southeastern Britain to partly depopulate it at the time of the English conquest (and I do mean the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes, not the Union of the Crowns). Though one might say with perfect truth that the English conquered southwest Britain militarily, it still took centuries before the natives adopted English, and the process is not yet complete.

Acilius: I know people feel strongly about names: as someone who must correct at least one person's mispronunciation of his name daily, I do too. What I object to is drawing inferences from names, or perhaps in the above case the appearance of having done so.

Picky said,

November 3, 2009 @ 9:24 am

Well, it wasn't rapid invasion and pitched battle on the 1939-1941 model of conquest, but then neither were the conquests by Europeans of India, Australia or equitorial and southern Africa. But conquests they were.

As to southeastern Britain, although I'm still attached to the history whereby the barbarians landed correctly at Thanet and overran the country from right to left with fire, sword (and no doubt the germ), I think the jury has retired again on whether there was substantial population replacement, either by war or by pestilence.

Picky said,

November 3, 2009 @ 10:10 am

Equitorial Africa must be the nicely balanced bit.

Luke said,

November 3, 2009 @ 1:33 pm

"Meanwhile, haven't we left out the British-American-Canadian conquest of North America? That seems to have been linguistically a bit of a wipe-out of native tongues, hasn't it?"

The case could be made that one of the reasons any of us are speaking English today is that there were a few Americans left in the 1940s who still spoke native languages.

marie-lucie said,

November 3, 2009 @ 10:22 pm

Too bad that the government didn't start encouraging the preservation of Native American languages at that time, when there were still sizable numbers of speakers, some of them children.