Ningbo pidgin English ditty

« previous post | next post »

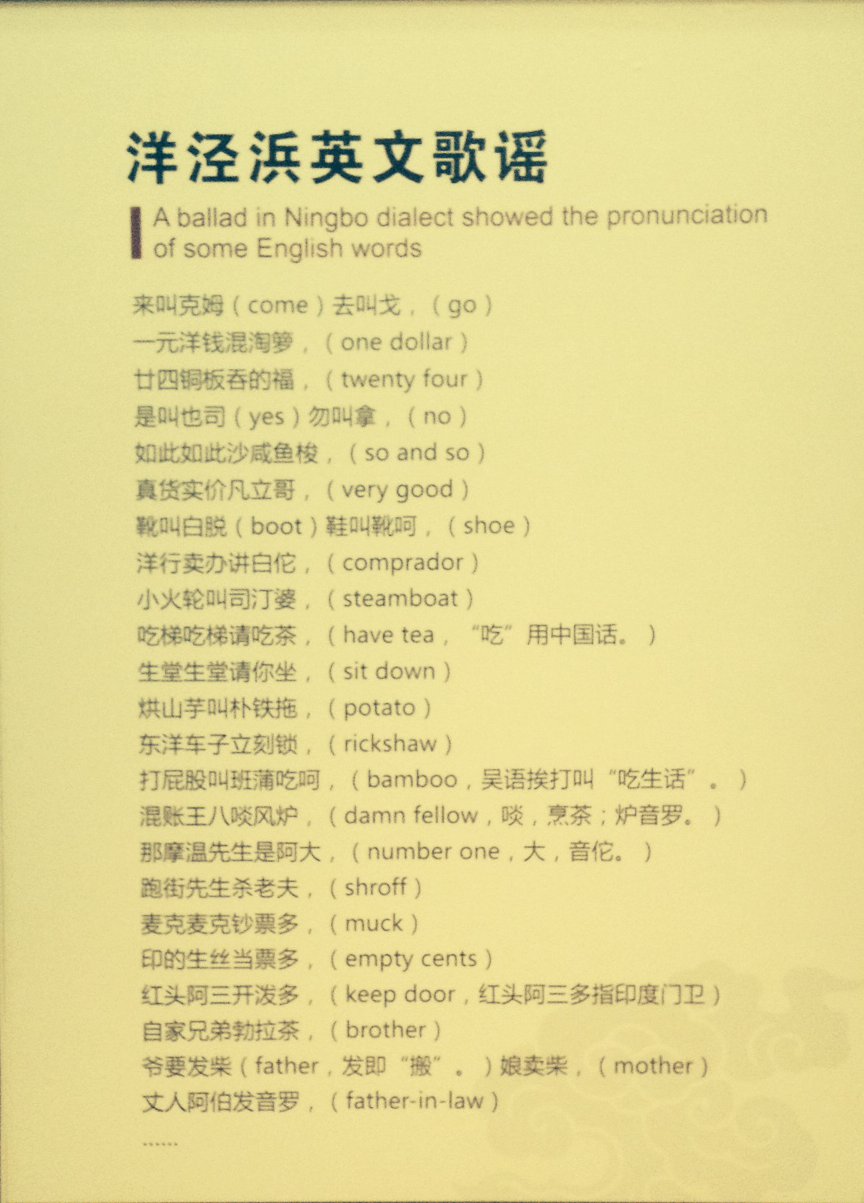

While visiting Ningbo last month, Barney Grubbs snapped this picture of a doggerel song featuring English words in local transcription at the Museum of the Ningbo Commercial Group ( Níngbō bāng bówùguǎn寧波幫博物館): Website, Wikipedia article.

The photograph is not clear (even with a magnifying glass it's hard to read), so a typed version is given below. [Update: Barney sent a clearer image of the verse — click to embiggen.]

Before taking a look at the language of the ditty, just a few words about Ningbo and the Ningbo Commercial Group.

Ningbo, located just south of the Hangzhou Bay, is a major seaport and commercial center. For centuries, merchants from Ningbo were active throughout East Asia, and some of the most influential entrepreneurs in Hong Kong and Taiwan (not to mention nearby Shanghai) come from Ningbo. Collectively, they are known as the Ningbo Commercial Group (English Wikipedia, Chinese Wikipedia).

Since I don't know Ningbonese, which belongs to the Wu branch of Sinitic, I cannot supply a transcription of the verse in that language. Though I tried to find a Ningbonese speaker who was able to provide a Romanized version, I was unsuccessful in doing so. Perhaps a Language Log reader will be able to help out in the comments (I'm sure that the phonetic resemblances would be much better in Ningbonese). Meanwhile, all that I can offer is a transcription in Modern Standard Mandarin (MSM):

lái jiào kèmǔ (come) qù jiào gē (go)

yīyuán yángqián hùn táoluó (one dollar)

niànsì tóngbǎn tūndefú (twenty-four)

shì jiào yěsī (yes) wù jiào ná (no)

rúcǐ rúcǐ shā xiányú suō (so and so)

zhēn huò shí jià fánlì gē (very good)

xuē jiào báituō (boot) xié jiào xuē'ā (shoe)

yángháng màilì jiǎngbáituó (comprador)

xiǎo huǒ lún jiào sītīngpó (steamboat)

chī tī chī tī qǐng chī chá (have tea)

shēng táng shēng táng qǐng nǐ zuò (sit down)

hōng shānyù jiào bǔtiětuō (potato)

dōngyáng chēzi lìkèsuǒ (rickshaw)

dǎ pìgu jiào bānpú chī'ā (bamboo; Wúyǔ āidǎ jiào"chī shēnghuó")

hùnzhàng wángbā dàn fēnglú (damn fellow)

nàmó wēn xiānshēng shì ā dà (number one)

pǎojiē xiānshēng shālǎofū (shroff)

màikè màikè chāopiào duō (muck)

yìnde shēngsī dàngpiào duō (empty cents)

hóngtóu āsān kāipō duō (keep door; hóngtóu ā sān zhǐ yìndù ménwèi)

zìjiā xiōngdì bólāchá (brother)

yé yào fāchái (father) niáng màichái (mother)

zhàngrén ābó fāyīnluō (father-in-law)

来叫克姆 (come) 去叫戈 (go)

一元洋钱混淘萝 (one dollar)

廿四铜板吞的福 (twenty-four)

是叫也司 (yes) 勿叫拿 (no)

如此如此沙咸鱼梭 (so and so)

真货实价凡立哥 (very good)

靴叫白脱 (boot) 鞋叫靴呵 (shoe)

洋行卖力讲白佗 (comprador)

小火轮叫司汀婆 (steamboat)

吃梯吃梯请吃茶 (have tea)

生堂生堂请你坐 (sit down)

烘山芋叫补铁拖 (potato)

东洋车子立刻锁 (rickshaw)

打屁股叫班蒲吃呵 (bamboo; 吴语挨打叫 "吃生活")

混帐王八啖风炉 (damn fellow)

那摩温先生是阿大 (number one)

跑街先生杀老夫 (shroff)

麦克麦克钞票多 (muck)

印的生丝当票多 (empty cents)

红头阿三开泼多 (keep door; 红头阿三指印度门卫)

自家兄弟勃拉茶 (brother)

爷要发柴 (father) 娘卖柴 (mother)

丈人阿伯发音罗 (father-in-law)

There's no need to provide a word for word translation, since each line consists of an expression in Ningbonese and its transcribed equivalent in English, with the original English words appearing in parentheses).

Brendan O'Kane, who not only sent Barney's photograph to me, but also kindly typed out the clear copy, offers these cogent remarks:

Lots of interesting stuff here, including the mention of Indian guards and the wonderful note about 吃生活 ("getting a taste of life?") being a Wu term for getting beaten. I wonder if 麦克麦克 isn't something more like "muckety-muck," given the gloss of 鈔票多 [VHM: "lots of cash"], though I see that the OED gives "money" as an obsolete sense of "muck." "Empty cents" was a new one for me, but according to Hanchao Lu's Street Criers: A Cultural History of Chinese Beggars, it was a term coined by compradors that eventually turned into the common Shanghainese biesan.

A couple of the transliterations (白脱 for "boot," 开泼 for "keep") sound kind of strange, but of course I've got no idea of how this sounds when read in Ningbohua.

A few additional notes:

jiào 叫 ("is called; means")

tóngbǎn 铜板 ("copper coins")

zhēnhuò shíjià 真货实价 ("real goods at a genuine price")

màilì 卖力 ("work hard; exert oneself")

dǎ pìgu 打屁股 ("beat on the buttocks")

hùnzhàng wángbā 混帐王八啖 ("bastard bastard")

xiānshēng 先生 ("Mister")

shì 是 ("is")

pǎojiē 跑街 ("salesman; travelling agent")

"Shroff" entered English in the 17th century. It comes from Portuguese xarrafo, which in turn derives from Hindi sarrāf ("moneychanger"), which is ultimately from Arabic. In Hong Kong English, you will still find "shroff" used to designate a cashier in a hospital, a government office, or a car park (parking garage). I was mystified when I first encountered this word at the newly opened Hong Kong International Airport on the island of Chek Lap Kok (there was a sign in the parking garage directing my host to "pay at the shroff").

For a detailed explanation of this term and its early usage, see Hobson-Jobson, pp. 831-832.

chāopiào duō 钞票多 ("lots of cash")

dàngpiào duō 当票多 ("lots of pawntickets")

hóngtóu āsān 红头阿三 ("red turbaned 'yessir' / 'I see'")

This is a word borrowed from Shanghainese hhongdhou'akse. It refers to Sikh policemen who were employed in the international settlements known as "concessions". They may still be seen in banks in Hong Kong and elsewhere, looking very imposing with their towering red turbans, full beards, and lethal weapons (often shotguns [sometimes sawed-off]).

zìjiā 自家 ("self" in Wu, corresponding to 自己 in Mandarin)

The potential of pidgin materials like this for understanding linguistic and cultural history is great, but we have barely begun to mine them. One of the first priorities in undertaking research on pidgin data is to gain better control of the local pronunciations and vocabulary on which they are based.

[Thanks to Richard VanNess Simmons]

julie lee said,

July 13, 2014 @ 12:18 pm

Thanks, I've heard of "Yang jing bang" (pidgin English of the Ningpo compradores) but this is the first actual example I've seen.

Re: 啖风炉 dan fenglu (in Mandarin) for "damn fellow". While I don't speak Ningponese, my inlaws are from Ningpo, and I know the final -ng and -n of Mandarin are nasalized in Ningponese.

So fenglu (Mandarin) would be more like felu ("fellow") in Ningponese.

Also, 戈 ge (in Mand.) for English "go": 戈 would be more like gu' in Ningponese.

Stephan Stiller said,

July 13, 2014 @ 12:52 pm

The English word "comprador" has a distinct colonial feel to me. It is old and little-seen these days, and I've only ever encountered it in discourse on historical Southern China. (I'm aware that Wikipedia talks about derived usage of the word in Marxism and for the developing world.)

Chris said,

July 13, 2014 @ 1:12 pm

"Shroff" occurs in Singapore too.

Victor Mair said,

July 13, 2014 @ 1:14 pm

From P'i-kou:

I find the 'ballad' in your post today absolutely delightful. I know no Ningbo, but Wu features are clearly visible in the transcription (e.g. an English voiced 'd' corresponds to pinyin t followed by tone 2 signalling a (creaky-)voiced 'd' in Wu; a final -an in Mandarin corresponds to a front open-mid vowel).

Roughly the same ballad seemingly appeared in 1935 in 汪仲賢 Wāng Zhòngxián's /Shànghǎi súyǔ túshuō/, an illustrated book explaining Shanghainese idioms.

http://www.worldcat.org/title/shanghai-suyu-tushuo/oclc/466331529

Here's an attribution of the ballad to Wang's book (source unclear):

http://www4.zzu.edu.cn/ces/show.aspx?id=354

And here apparently we have its occurrence in Wang's text, copy-pasted in some forum:

http://www.kqbd.com/bbS/forum.php?mod=viewthread&tid=56138

Let me remark that there is no mention of Ningbo, and that the transcription of the ballad as we have would seem compatible with a Shanghainese origin. Indeed, I would expect the distinction between the Ningbo and Shanghai dialects to be quite blurred in an early 20th century, Yangjing bang/Ningbo clique context, where a large fraction of 'Shanghainese' speakers would actually come from northern Zhejiang.

An article on the /Ningbo ribao/, probably based on sources from the museum itself, attributes the Ballad to Ningbo clique arch-compradore Mù Bǐngyuán 穆炳元, a native of Dinghai (Zhoushan archipelago).

http://daily.cnnb.com.cn/xqb/html/2012-03/23/content_445223.htm

About Mu Bingyuan:

http://cross-currents.berkeley.edu/sites/default/files/e-journal/articles/si.pdf

http://zh.wikipedia.org/zh-hant/%E7%A9%86%E7%82%B3%E5%85%83

To this day, 'Yangjing bang' in Shanghainese (in which this particular expression sounds (very roughly) like in Mandarin) is still used to mean 'sloppy' or 'inexpert'. The 'bang' itself no longer exists; I think Xizang nan lu runs over where it was. Here is how it looked back in the day:

http://www.360doc.com/content/10/0510/14/178233_26916597.shtml

If you enjoy Chinese Pidgin English as much as I suspect, you might like Charles Lelands's 1876 /Pidgin-English Sing-song/:

https://archive.org/details/pidginenglishsin00lelaiala

I for one am a big fan of CPE. Its sources, and its influences, go beyond just Chinese and English. An example: CPE "joss" meaning 'Chinese deity; image of a deity' comes ultimately from Portuguese Deus 'God'; besides derivatives like "joss house" (temple) within CPE and "joss stick" in Standard English, in Dutch (as joos/joosje/joost) it has come to mean 'the devil', as "Joost mag het weten" 'Joost may know it' = 'who knows?' Sources for the etymology and the Dutch connection:

http://old2013.cssn.cn/55/5500/201304/t20130424_347263.shtml

http://www.etymologiebank.nl/trefwoord/joosje

http://www.wnt.inl.nl/iWDB/search?actie=article_content&wdb=WNT&id=M028993

Barney Grubbs said,

July 13, 2014 @ 3:05 pm

This is great! Thanks for the additional background. It was a fascinating museum even if it left one with the impression that the Ningbonese diaspora secretly runs the world.

julie lee said,

July 13, 2014 @ 4:54 pm

P'i-kou:

I'm flabbergasted that "joss" in joss-stick (incense stick) comes from Portuguese Deus. Who would have imagined it, and yet, of course. Thanks.

Re Ningpo. Having been an international port for hundreds of years, its people tended to be much more cosmopolitan and modern than those of most other provinces. My mother-in-law was from a merchant family in Ningpo and father-in-law from the landed gentry in Shandong. She was always making fun of how backward his thinking was.

Alex said,

July 13, 2014 @ 8:27 pm

@Stephen Stiller. You're right. "Comprador" is not English by origin, nor would it be understood by most monolingual English speakers. It's another loanword from Portuguese (probably, though the word is the same in Spanish), and that could neatly explain its observed restriction to times and places where Portuguese and English colonialism bumped up against each other.

William Steed said,

July 14, 2014 @ 12:20 am

Here's my Wu pronunciation version, based on the 简明吴方言词典, which uses conservative Shanghai pronunciation, not taking tone sandhi into account (Ningbonese sandhi is considerably different to that of Shanghai). Although Shanghainese pronunciation is heavily influenced by Ningbonese, you would expect some vowel differences, I suspect, particularly where there is an -u where you would expect -o.

Although it appears here, most Wu pronunciations will not have a glottal stop except in word final position; instead you will find a short vowel as part of the tone production. As Julie Lee said, the nasal syllable codas are usually weaker (or perhaps non-existent?) in Ningbonese.

来叫克姆 (come) 去叫戈 (go) ku53

一元洋钱混淘萝 (one dollar) ɦuəŋ13 dɔ13 lu13

廿四铜板吞的福 (twenty-four) tʰuŋ53tiɪʔ5foʔ5

是叫也司 (yes) 勿叫拿 (no) ɦia13sz53

如此如此沙咸鱼梭 (so and so) so53ɦɛ13ŋ13su53

真货实价凡立哥 (very good) vɛ13liɪʔ2ku53

靴叫白脱 (boot) 鞋叫靴呵 (shoe) paʔ5tʰoʔ

洋行卖力讲白佗 (comprador) kaŋ34paʔ5du13

小火轮叫司汀婆 (steamboat) sz53tʰiŋ53bu13

吃梯吃梯请吃茶 (have tea) tɕʰiɪʔ5tʰi53

生堂生堂请你坐 (sit down) səŋ23taŋ34

烘山芋叫补铁拖 (potato) pu34tʰiɪʔ5tʰu53

东洋车子立刻锁 (rickshaw) liɪʔ2kʰəʔ5su34

打屁股叫班蒲吃呵 (bamboo; 吴语挨打叫 "吃生活") pɛ53bu13tɕʰiɪʔ5aʔ5 (bamboo chair?)

混帐王八啖风炉 (damn fellow) dɛ13foŋ53lu13

那摩温先生是阿大 (number one) na13mo13uəŋ53 (actually a dictionary entry)

跑街先生杀老夫 (shroff) saʔ5lɔ13fu53

麦克麦克钞票多 (muck) maʔ2kʰəʔ5

印的生丝当票多 (empty cents) iŋ34tiɪʔ5səŋ53sz53

红头阿三开泼多 (keep door; 红头阿三指印度门卫) kʰɛ53pʰəʔ5tu53

自家兄弟勃拉茶 (brother) bəʔ2la53zo13

爷要发柴 (father) 娘卖柴 (mother) faʔ5za13 ma13za13

丈人阿伯发音罗 (father-in-law) faʔ5iŋ53lu13

Jason Stokes said,

July 14, 2014 @ 12:54 am

@Victor Mair

That Chinese Pidgin English song book is simply marvellous. Doubtless there are errors and Anglicisms and the pseudo-English spelling is distracting, but getting a chance to read an extended text in it, I realise that CPE is so eerily similar to the creoles/pidgins that I am familiar with — the family that encompasses Australian Aboriginal Kriol, Torres Straight Creole (Yumplatok), Tok PIsin, and Bislama — that I understand why some people think CPE should be regarded as the ancestor of all the other pidgin Englishes found throughout the world. I now want to read up on the relationship of CPE to the other English creoles, the South Pacific, Nigerian Pidgin, Native American pidgin, African American Creole, etc.

bratschegirl said,

July 14, 2014 @ 2:11 am

When did "embiggen" become a thing? This is the second place I've encountered it. Wonderfully silly and utterly useful word.

bratschegirl said,

July 14, 2014 @ 2:13 am

Never mind – shoulda known I'd find it myself if I used the search box above!

julie lee said,

July 14, 2014 @ 11:31 am

Victor Mair:

Thanks for the paragraph on Ningpo entrepreneurs and the Wikipedia link. It so happens a Ningpo relative of mine told me that, as a result of the Communist takeover of China by Mao in 1949, a lot of Shanghai business tycoons fled to Hong Kong, bringing their business expertise with them and transforming Hong Kong's position in the business world. He himself, a businessman, had also fled from Shanghai after Mao's takeover. He said all the top business tycoons in Hong Kong were his friends from Shanghai. He mentioned two Ningpo natives like himself, Chen Din Hwa (H.K.textile magnate and shipping magnate) and Chao Kuang Piu (H.K. textile magnate). Textiles had been the top or one of the top industries in Shanghai. Said men like them moved the Shanghai textile industry to Hong Kong (which then flooded the U.S. with textiles in the 50s and 60s, eventually killing the textile industry of New England in the U.S.) Many Shanghai tycoons like these two were from Ningpo. Ningpo had lost its international status and many Ningpo poeple went to Shanghai for education and their careers. On another note, regarding the influence of Hong Kong business talent on the U.S., the journalist Frank Viviano wrote in San Francisco Chronicle (1980s) which said that from his interviews he learned that all the top Chinese businessman in San Francisco were from one English-language school in Kowloon, the Diocesan School, a top school in H.K. for at least a hundred years.

P'i-kou said,

July 14, 2014 @ 1:49 pm

@William Steed

Thanks a lot for that transcription!

I think the 'get caned' item is actually "bamboo chow-chow", where "chow-chow" means 'eat' or 'food', apparently attested in CPE with this meaning (Shanghainese (or other Wu?) 吃生活 tɕʰiɪʔ səŋɦo 'eat life' = 'get a taste of life' as in the post > 'eat bamboo' = 'get a caning'). That would explain the 吃生活 note in the original picture, which otherwise wouldn't make much sense.

吃呵 would be a plausible transcription for "chow" if we assume 呵 is pronounced like 河, which should be something like [ɦ] plus a rounded vowel.

The Sing-song book quoted in my previous comment (channelled by Prof. Mair) has some occurrences of "chow-chow" meaning 'food' or 'eat'.

In a slightly different rendition of the ballad (that supposedly goes back to its appearance in print in that Wang Zhongxian book I mentioned earlier) has 曲 instead of 吃呵 in the 'bamboo' part. I think 曲 is something like [tɕʰaʔ], which doesn't help a lot. The authors of the article I just linked to speculate that this 曲 transcribes "chop", which of course is a CPE word but doesn't really belong here.

They also suggest "mark" where we have "muck".

P'i-kou said,

July 14, 2014 @ 2:13 pm

@julie lee

Not to mention the less-than-universally loved former CE Tung Chee-hwa 董建華, who has been in the news again of late. Tung is the son of a Ningbo bang shipping magnate.

To stay on the topic of Ningbo Wu, the "Chee" for 建 (Mandarin jiàn in Tung's name looks like a (not very conservative) Wu pronunciation. Modern Shanghainese at least has lost the -an from the endings spelled -ian in Pinyin, but it still had them in the late 19th century (as evidenced e.g. here) and I think they still survive in certain contexts, e.g. 'stage' pronunciation.

julie lee said,

July 14, 2014 @ 3:54 pm

@P'i-kou,

Oh, I always thought Tung Chee-hwa was a Shanghainese. Again, that shows the Shanghai-Ningbo connection.

I was surprised to see in the Wikipedia article (in Victor Mair's original post) that Run Run Shaw, who practically founded and owned the thriving Hong Kong movie industry was from Ningbo. Because he was so big in H.K., I always thought he was Cantonese. The story in high Chinese social circles in Singapore was that the Shaw brothers started out as street peddlers or hawkers, as did many Chinese zillionaires in Singapore and Malaysia.

Victor Mair said,

July 15, 2014 @ 11:50 pm

Geoff Wade has called my attention to the Ningbo Association in Hong Kong, where there is a lovely restaurant (open to the public).