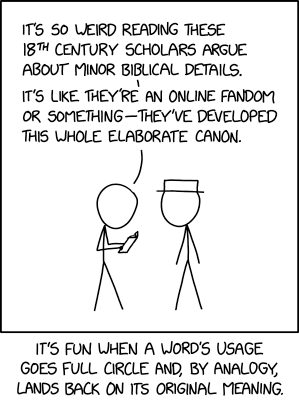

Canonical circles

« previous post | next post »

Mouseover title: "Achilles was a mighty warrior, but his Achilles' heel was his heel."

The history of canon is certainly fun, at least for those of us who enjoy semantic drift. But the circular drift is older than xkcd suggests. And the circle is arguably still incomplete, given Wiktionary's etymology:

From Middle English canoun, from Old French canon and Old English canon, both from Latin canōn, from Ancient Greek κανών (kanṓn, “measuring rod, standard”), akin to κάννα (kánna, “reed”), from Semitic (compare Hebrew קָנֶה (qane, “reed”) and Arabic قَنَاة (qanāh, “reed”)).

The OED's sense 1.a. of canon

A rule, law, or decree of the Church; esp. a rule laid down by an ecclesiastical Council. the canon (collectively) = canon law n.

…goes back to Old English, with citations from the 4th century. And OED sense 4

The collection or list of books of the Bible accepted by the Christian Church as genuine and inspired.

…has citations back to the 14th century. The earliest citation for the figurative extension ("any set of sacred books; also, those writings of a secular author accepted as authentic") is from the Encyclopedia Britannica in 1885:

The dialogues forming part of the ‘Platonic canon’.

…which is still long before the "online fandom" usage — but I'm guessing that there are earlier examples, certainly for the adjectival form canonical, which long ago joined the online fandom and Wiktionary's sense 10 in extending to the content of the canonical sources:

(chiefly fandom slang, uncountable) Those sources, especially including literary works, which are considered part of the main continuity regarding a given fictional universe; (metonymic) these sources' content.

I'm not sure whether that extension of canon can be found in in the 18th century, but for canonical the OED cites

A poore mans speech is seldome pleasant, and wisedome vnder a ragged coate seldome canonicall. (Henry Crosse, Vertues common-wealth; or, The high-way to honour, 1603.)

And there's more canonical fun available, since other English descendants from the same botanical source include cannon, canyon, canal, maybe can, and of course cane.

Robert Coren said,

August 3, 2025 @ 9:51 am

Plus there's the musical sense, designating a piece (or passage) where one voice follows another in strict imitation; I assume the idea behind this usage is that the music follows a "rule", one might say, religiously.

Scott P. said,

August 3, 2025 @ 11:01 am

Robert:

Probably because music of that kind was often sung by canons: i.e. the members of a cathedral chapter.

S Frankel said,

August 3, 2025 @ 1:30 pm

(PhD in historical musicology here). Robert is right. There were secular canons as early as sacred ones, typically of the 'Three Blind Mice' type, although these were called 'rotae' (wheels) or 'rounds'. The word "canon" doesn't come in until the the 16th century, and theorist from the time explicitly define it as music determined by a canon or rule. And secular canons continued to be popular. There are some examples in the Wiki article.

unekdoud said,

August 3, 2025 @ 1:41 pm

"genuine and inspired" seemed a bit surprising to me, so I checked and there is indeed a religious sense involved.

Peter Taylor said,

August 3, 2025 @ 3:04 pm

The Spanish cognate cañada can mean canyon, cattle trail (perhaps because of the switches used to drive cattle?), bone marrow, or a bovine leg bone.

wgj said,

August 3, 2025 @ 4:08 pm

I find "Achilles' heel" much more interesting – do most languages (outside the hellenophile cultural sphere) have a non-literal expression for the same meaning?

The equivalent Chinese expression 七寸 (seven inches) is itself a fascinating linguistic gem.

Jonathan Smith said,

August 3, 2025 @ 4:26 pm

Shouldn't the joke be "it's weird reading (say) the 14th-15th c. decrees of the Councils of Florence/Trent regarding an authoritative New Testament, they've developed this whole elaborate canon" or sth.?

Also FWIW Wikipedia claims that "Athanasius, Bishop of Alexandria, gave a list of exactly the same books that would formally become the New Testament canon and […] used the word 'canonized' (κανονιζομενα) in regard to them" in 367, so canon = orthodox Bible may be a millennium earlier than the 14th c. at least in some of the relevant languages…

Andrew McCarthy said,

August 3, 2025 @ 5:00 pm

One of the people most responsible for the adoption of the term "canon" in non-Biblical contexts is Ronald Knox, a well-known author and critic of detective fiction in early 20th-century England, who applied the term to the collected stories of Sherlock Holmes by Arthur Conan Doyle.

Knox would have known and appreciated the tongue-in-cheek, mildly heretical flavor of the non-religious usage, since in his day job he was a Catholic priest!

Andrew McCarthy said,

August 3, 2025 @ 5:06 pm

On further reflection, I might be wrong about Knox using the term "canon" in his writings on Sherlock Holmes. But he certainly grasped the spirit of it, as in his 1911 satirical essay "Studies in the Literature of Sherlock Holmes", which treats the Holmes stories as narratives whose veracity is not to be doubted, in the manner of Biblical exegesis – a tongue-in-cheek approach that has influenced Holmes fandom to this day.

J.W. Brewer said,

August 3, 2025 @ 6:04 pm

21st century online fandoms developed from mid/late 20th century offline fandoms, all primitive and analog, and i daresay the fannish sense of "canon" was likely already extant in the latter.

Mark Liberman said,

August 3, 2025 @ 7:35 pm

@Jonathan Smith: "Also FWIW Wikipedia claims that "Athanasius, Bishop of Alexandria, gave a list of exactly the same books that would formally become the New Testament canon and […] used the word 'canonized' (κανονιζομενα) in regard to them" in 367, so canon = orthodox Bible may be a millennium earlier than the 14th c. at least in some of the relevant languages…"

Update: as ktschwartz points out, 376 is the page number, not the year! — sorry for the stupid mistake, I should have known better!

The OED quotes "Ða canonas openlice beodaþ" from the Laws of Ælfred, 376 — I described this vaguely as "citations from the 4th century", but it seems that Ælfred was less than a decade behind Athanasius, though apparently referencing canonical principles rather than canonical works?

ktschwarz said,

August 3, 2025 @ 8:32 pm

"The 4th century"??? King Alfred the Great lived in the 9th century, not the 4th — that's half a millennium off! The Laws of Ælfred were dated at "a900" in print editions of the OED; the online version more cautiously refrains from fixing any dates for that period, and just puts the quotation in "OE". 376 is the page number in the edition they're citing, not the date.

Daniel Deutsch said,

August 4, 2025 @ 4:57 am

@Robert Coren: Yes, in musical canons a voice may follow another in strict imitation, but in many ingenious examples the imitation is transformed by transposition, inversion, retrograde-inversion, augmentation, or diminution.

Mark Liberman said,

August 4, 2025 @ 5:16 am

@ktschwartz: "King Alfred the Great lived in the 9th century, not the 4th — that's half a millennium off! The Laws of Ælfred were dated at "a900" in print editions of the OED; the online version more cautiously refrains from fixing any dates for that period, and just puts the quotation in "OE". 376 is the page number in the edition they're citing, not the date."

Sorry, I should have known better!

Bob Ladd said,

August 4, 2025 @ 5:24 am

@ktschwarz: I can't believe I read "goes back to Old English, with citations from the 4th century" in MYL's original post yesterday without having the WTF experience that you have diplomatically reported. Thanks for explaining the "376", too.

bks said,

August 4, 2025 @ 5:46 am

From the Unix fortune program:

Canonical, adj.:

The usual or standard state or manner of something. A true

story: One Bob Sjoberg, new at the MIT AI Lab, expressed some

annoyance at the use of jargon. Over his loud objections, we made a

point of using jargon as much as possible in his presence, and

eventually it began to sink in. Finally, in one conversation, he used

the word "canonical" in jargon-like fashion without thinking.

Steele: "Aha! We've finally got you talking jargon too!"

Stallman: "What did he say?"

Steele: "He just used `canonical' in the canonical way."

Tom said,

August 4, 2025 @ 8:51 am

Perhaps the story about Ronald Knox is apocryphal.

@wgj

We also have from Hellenistic antiquity, "from his foot, you will know Hercules" and "feet of clay". I wonder what other foot-related expressions are out there.

Anthony said,

August 4, 2025 @ 9:56 am

Somewhat foot-related, there's that ridiculous "bootstraps" business.

MC said,

August 4, 2025 @ 11:35 am

Yes, Daniel Deutsch, the list of all the particular ingenious transformations in a musical canon, including when subsequent voices enter, constitute the "rule" or "canon" for the composition. For a canonic composition, a composer could choose to present his composition as a single voice and then give a written rule for the performers to follow to realize the complete composition.

Daniel Deutsch said,

August 4, 2025 @ 3:17 pm

Thanks for pointing that out, MC. Indeed the rule was sometimes expressed as a puzzle that had to be solved in order to realize the composition.

Brett said,

August 5, 2025 @ 3:19 pm

@Tom: Feet of clay is older than Hellenistic. It's from the Book of Daniel. Of course, that almost certainly means it wouldn't have become a standard metaphor in the broader Mediterranean world until imperial Roman times.

GH said,

August 5, 2025 @ 11:38 pm

@Brett:

The Book of Daniel dates to the Hellenistic era.

Neil H Dolinger said,

August 8, 2025 @ 7:42 am

I’d be interested in knowing what “reed/cane” metaphor the original coiners of “canon” were thinking about. Were they looking at the use of a cane to funnel acceptable content into the collection? Were they thinking about the enforcement/punishment uses of canes for those who transgressed the official designation of which books were acceptable? Another metaphor entirely?