Borrowability

« previous post | next post »

One of the most interesting talks that I've heard so far, here at the Linguistic Society of America's annual meeting, was Uri Tadmor and Martin Haspelmath, "Measuring the borrowability of word meanings". I haven't yet been able to get a copy of the slides for their presentation here, but web search turned up the abstract for a talk of the same title at the upcoming Swadesh Centenary Conference, and the slides from a talk entitled "Loanword Typology: Investigating lexical borrowability in the world's languages", given at a recent workshop "New Directions in Historical Linguistics"(Université de Lyons, May 12-14 2008).

[Update: the slides from their LSA talk are now here, and additional information is available on the project website. I'll update the rest of this post to match when I have a chance. Meanwhile, Uri emphasizes that the LSA results are preliminary, and the Lyons report even more so.]

[Update #2: Uri answers questions in a guest post here.]

As you can learn from those links, their project investigated the words for 1460 "meanings" in 30 languages, allowing for a many-to-many relationship between words and meanings. They recruited an expert for each language to find the relevant words and to determine various properties for each one, including whether it had been borrowed from another language. The resulting database will be posted on the web at some point in the not-too-distant future.

(Since I haven't yet been able to get a copy of yesterday's slides, the numbers and lists below come from their May presentation, and so are somewhat out of date, since as I understand it, the construction and checking of the database is not quite complete even now.)

The most loanword-friendly languages (in their set of 30) were Selice Romani (60%), Tarifiyt Berber (48%), Romanian (40%), English (39%), and Sramaccan (34%). The most loanword-resistant languages were Mandarin Chinese (1%), Ket (7%), Manage (7%), Seychelles Creole (8%), and Gurindji (9%).

The most borrowable word meanings were kangaroo (100%), olive (100%), motor (96%), camel (95%), coffee (93%).

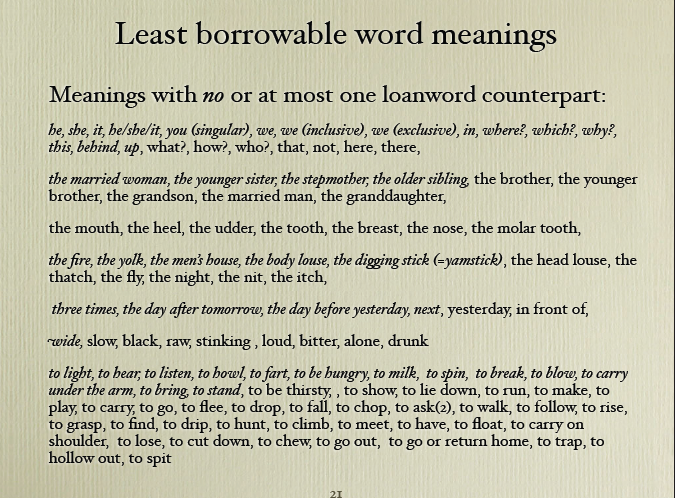

Here's their slide for the other end of the scale (click for a larger version):

There are several reasons for being interested in this sort of thing, but one of the most important ones is the reason that motivated Morris Swadesh to compile his list, half a century ago.

bulbul said,

January 10, 2009 @ 12:32 pm

The article on loanwords in Selice Romani is available online.

Joseph Dart said,

January 10, 2009 @ 12:36 pm

The most borrowable word meanings were kangaroo (100%)

How is that 100% even possible, given that Chinese invented/calqued its own word to refer to them (one which literally translates as "pocket mouse")?

bulbul said,

January 10, 2009 @ 12:43 pm

So let me get this straight: one of the top five most loanword-friendly languages is a creole and one of the top five most loanword-resistant languages is also a creole? Well shave my back and call me a beaver. I'd love to see the same study done on Maltese…

Craig Russell said,

January 10, 2009 @ 1:25 pm

I'm a little confused about the nature of this list. If I'm understanding it right, the assertion behind the slide is:

This is a list of 'meanings' for which the word in the 30 languages we studied is not a loanword (or is a loanword in only one of the languages if the word's not italicized).

My problem is this: how do you determine what "THE word" for a meaning in a language is? English has multiple words for several of these concepts: e.g. "drunk". Obviously the word "drunk" itself goes back to Old English, but we have loanwords that express the same concept (e.g. "inebriated" from Latin; "intoxicated", ultimately from Greek). Is the assertion, then, that each of these words has at least one non-loanword in each language?

How about concepts for which there is no one word in a language? E.g. I assume by "the married woman" they not thinking of the English "wife" (which names a woman from the point of view of her husband). If this is so, what word does English have for this concept? The only one I can think of is "matron", which is a loanword from French–as is the word "married" itself, if we're counting the English phrase "married woman" as THE word in English for this concept.

[(myl) With respect, I'm puzzled. The post says, "their project investigated the words for 1460 "meanings" in 30 languages, allowing for a many-to-many relationship between words and meanings". The Lyons slides, which I linked to, provide this example (on slide 15):

But you write: "how do you determine what 'THE word' for a meaning in a language is? English has multiple words for several of these concepts". Did you really not understand that they explicitly allowed for one word to correspond to several meanings, and for one meaning to be linked to several words? I'm troubled about even trying to respond further, because I worry about whether you would read the explanation carefully enough to understand it. ]

m-vic said,

January 10, 2009 @ 1:34 pm

Interesting topic indeed. Did they mention any correlation with how receptive the various cultures are to foreign influence? (Not that you could really quantify that). I didn't see anything like that on the slides. I also wonder why Mandarin is only at 1% – with such a widely spoken language, in a multilingual country especially, you might expect to find dialect borrowings, or loans from related languages spoken nearby. But those are probably harder to detect.

bulbul said,

January 10, 2009 @ 2:23 pm

Craig,

exactly. Plus, since professor Liberman mentioned the Swadesh list, I have to wonder about the choice of some concepts / words. In that paper on Selice Romani, Viktor Elšík provides a list of loans which includes words like

cukornádo ‘sugar cane’

lagúna ‘lagoon’

papagáji ‘parrot’

jaguári * ‘jaguar’

tekňéšbíka ‘turtle’

and so forth. Those are not only imported words, but also imported items and thus with little relevance to lexicostatistics and glottochronology.

They may be very relevant to sociolinguistics and sociology, though – the fact that these particular ones were imported from Hungarian (another minority language) and not Slovak (the official and majority language) is certainly noteworthy.

John Cowan said,

January 10, 2009 @ 3:11 pm

I make the borrowed morphemes in the English version to be married, sibling, grand-, molar (though it's just a Latinate rendering of native grinder), front, carry.

Sky Onosson said,

January 10, 2009 @ 3:14 pm

Joseph Dart said" The most borrowable word meanings were kangaroo (100%) How is that 100% even possible, given that Chinese invented/calqued its own word to refer to them (one which literally translates as "pocket mouse")?"

Perhaps if they also borrowed the word, it was counted as an instance of borrowing, whether or not there were additional calques in the language.

Craig Russell said "I'm a little confused about the nature of this list. If I'm understanding it right, the assertion behind the slide is: This is a list of 'meanings' for which the word in the 30 languages we studied is not a loanword (or is a loanword in only one of the languages if the word's not italicized)."

I take it that they were looking for cases of loanwords with the relevant meanings in the surveyed languages, but not whether the loanwords were the word for a given concept.

J Greely said,

January 10, 2009 @ 3:26 pm

When the native experts determined the correct words for each meaning, did they discount loanwords that existed alongside native words?

For instance, in Japanese, the loanword "waido" is definitely in wide (ahem) use alongside hiroi and ookii, with the native words overlapping a bit and covering a wider range of situations. Waido is definitely not confined to consumer electronics (wide-screen), tv/radio (wide-news), and parts of other loanwords (world-wide), even if those uses are so common they're hard to weed out of a google search, but even in those areas, you see hybrids like waido-gamen (screen) and waido-yuushi (financing).

There's a clean example of waido in the Tanaka Corpus: いつもワイドな視野を持って、仕事をしなさい ("Itsumo waido-na shiya wo motte, shigoto wo shi-nasai" = "You should always keep a broad perspective on the work you do").

-j

blahedo said,

January 10, 2009 @ 3:31 pm

Sky Onosson's guess sounds pretty reasonable given the word list and an intuition about what you might want to know—who cares if someone came up with a calque, do the people on the ground prefer a loanword? (Or rather, we might also care about that, but it's a separate question.)

Doesn't answer the question about matron, though, which definitely does mean "married woman". Perhaps they don't consider it enough of a loan? Or that the loan was so long ago it doesn't matter? That's possible, since otherwise you run the risk of categorising a huge percentage of English words as "loans"; presumably they ran into a similar issue with the creoles. I suppose they could think that nobody these days actually uses the word "matron", although there they'd simply be wrong.

bulbul said,

January 10, 2009 @ 4:22 pm

FYI, these are the project guidelines which include a list of lexical meanings (LWT meaning list) with optional definitions and examples of usage. Item with the code 2.39 "the married woman" does not have a definition, but there is a sample sentence:

"As a married woman she had more privileges."

Note that the guidelines say that the LWT meaning list "is not a list of English words". So if I get this right, 'lexical meaning' roughly equals 'concept' and they were asking if those particular concepts were expressed by a loanword or by a native word. That still doesn't explain 'kangaroo', especially since the guidelines (3.2) specify that "Only established, conventionalized loanwords that are felt to be part of the language should be given, not nonce borrowings."

And as for "the married woman", according to the guidelines (ibid.): "The word form can be a single word, or a phrasal expression, which must be a fixed one. It is not clear to me from the examples they give ('feather' expressed as 'hair of bird' vs. 'to make love' meaning 'to have sex') what "the married woman" is.

dr pepper said,

January 10, 2009 @ 6:31 pm

When they say a creol is loanword resistant, do they mean for any words or just for words other than from the parent languages?

bulbul said,

January 10, 2009 @ 8:09 pm

dr pepper,

based on the numbers, I'm assuming that they mean "words from languages other than the lexifier". In case of Saramaccan that would mean that they consider 30% of Portuguese-derived vocabulary loanwords.

bulbul said,

January 10, 2009 @ 8:12 pm

I meant of course "that portion of Saramaccan vocabulary derived from Portuguese which consistutes about 30% of the entire Saramaccan vocabulary". Or something like that. It late. Me need sleep.

The other Mark P said,

January 11, 2009 @ 4:19 am

I suppose they could think that nobody these days actually uses the word "matron", although there they'd simply be wrong.

Definitely. A matron is a woman who helps run a boarding house or similar. Or a senior nurse. Or a woman of undefineable age and conservative outlook. But in either case her marital status is immaterial.

I doubt if more than 1 in a 100 people would be able to give "matron" as the correct answer for a single word that describes a married woman. I was unaware of that meaning until now.

Craig Russell said,

January 11, 2009 @ 12:44 pm

@myl

I had only read the original version of your post, in which you didn't have a link to the slides of the presentation. That was the version I was commenting on, so when I asked the question I asked, I hadn't seen the fuller explanation given by the full set of slides.

Philip Spaelti said,

January 11, 2009 @ 1:04 pm

Thank you Mark for this truly fascinating post. Also for the follow up comment to Craig Russell's comment. I for one had overlooked the first set of slides. They really cleared things up for me.

Anyhow I get the feeling that a lot of commenters are misunderstanding what Haspelmath et al. are trying to do here. Clearly they are trying to assemble a balanced database with comparable sets of data. All generalizations are then based on this database. At that point one has to resist the tendency to say "I can think of language X which does have a borrowed word for Y". Of course you can. The English set has 1504 words 1460 meanings. But equiped with Roget's Thesaurus, I'm sure anyone could quickly boost the number to several thousand, the vast majority borrowings. But that would make the English data set uncomparable with, say, that of Saramaccan. Similarly it's wrong to criticize individual numbers. That kangaroo's borrowing comes to 100% is an artifact. But surely we *expect* kangaroo to be highly borrowed. In fact since only a handful of the world's 6000 languages are likely to have a native word 100% is probably not far off the mark. So this number is confirmation that Haspelmath's database is not completely off the mark.

Much more interesting are other cases. I think it's interesting that "wide" is less likely to be borrowed than "big" or "small" or "long". Similarly the slides show that a number of Swadesh words are surprisingly bad choices. Who would have thought that "tree" had 36% borrowability? (After the fact I can think of reasons, but I sure wouldn't have guessed it.)

Craig Russell said,

January 11, 2009 @ 1:11 pm

Oops–

Okay, now I see that the Lyons slides were there from the beginning. Sorry for posting without looking at these. The point about the database allowing for many-to-many relationships answers my first question, and I should have read more carefully.

language hat said,

January 12, 2009 @ 12:16 pm

Tarifiyt Berger

Berber, surely?

Chris said,

January 16, 2009 @ 1:41 am

@J Greely: not only were they not discounted, but they were also an integral part of the database. But I tried to include only fairly commonly used words, so waido was out.

Bathrobe said,

May 19, 2011 @ 8:01 pm

Strangely, Chinese is not the only language to have its own word for 'kangaroo'. In Mongolian the kangaroo is known as имж (imj). I have no idea where it came from or why Mongolians would come up with their own word for 'kangaroo'.

Looking at some of the lists at their site, it's obvious that they've been careful to check what are borrowings and what are not, but there are some grey areas. This is especially so for Chinese, where borrowings can be masked by the script.

For example, Chinese 父亲 is given as 'no evidence for borrowing', but my understanding is that it comes from Japanese ちちおや. I'm afraid I can't find a source for this, but I'm pretty sure that words like 爹 or 爸爸 represent the normal word for 'father'; 父亲 is a high-flown, official-sounding word that was borrowed (visually) from Japanese and has gradually spread in relatively recent times. Borrowings between Chinese and Japanese in modern times are a fraught area where the direction of borrowing is not always what it appears.

The list also fudges a bit on words created using foreign elements. 男兄弟 otoko-kyōdai is given as 'no evidence for borrowing', but while the expression as a whole is not borrowed, it is a transparent combination of a native word (男) and a borrowed word (兄弟). I'm sure they have their criteria (e.g., coinages created from borrowed elements are not themselves treated as borrowed terms), but the result looks somewhat arbitary.

ประกันภัยรถยนต์ said,

July 28, 2014 @ 11:01 pm

Thank you Mark for this truly fascinating post. Also for the follow up comment to Craig Russell's comment. I for one had overlooked the first set of slides. They really cleared things up for me.