Speaker-change offsets

« previous post | next post »

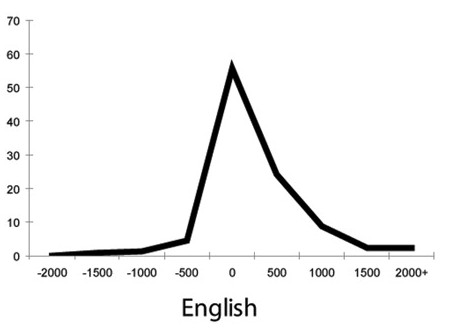

In Meg Wilson's post on marmoset vs. human conversational turn-taking, I learned about Tanya Stivers et al., "Universals and cultural variation in turn-taking in conversation", PNAS 2009, which compared response offsets to polar ("yes-no") questions in 10 languages. Here's their plot of the data for English:

Based on examination of a Dutch corpus, they argue that "the use of question–answer sequences is a reasonable proxy for turn-taking more generally"; and in their cross-language data, they found that "the response timings for each language, although slightly skewed to the right, have a unimodal distribution with a mode offset for each language between 0 and +200 ms, and an overall mode of 0 ms. The medians are also quite uniform, ranging from 0 ms (English, Japanese, Tzeltal, and Yélî-Dnye) to +300 ms (Danish, ‡Ākhoe Hai‖om, Lao) (overall cross-linguistic median +100 ms)."

So for today's Breakfast Experiment™, I decided to take a look at similar measurements from one of the standard speech-technology datasets, namely the 1/29/2003 release of the Mississippi State alignments of the Switchboard corpus. For details on the corpus itself, see J.J. Godfrey et al., "SWITCHBOARD: telephone speech corpus for research and development", IEEE ICASSP 1992). Here's a random selection from one of the conversations:

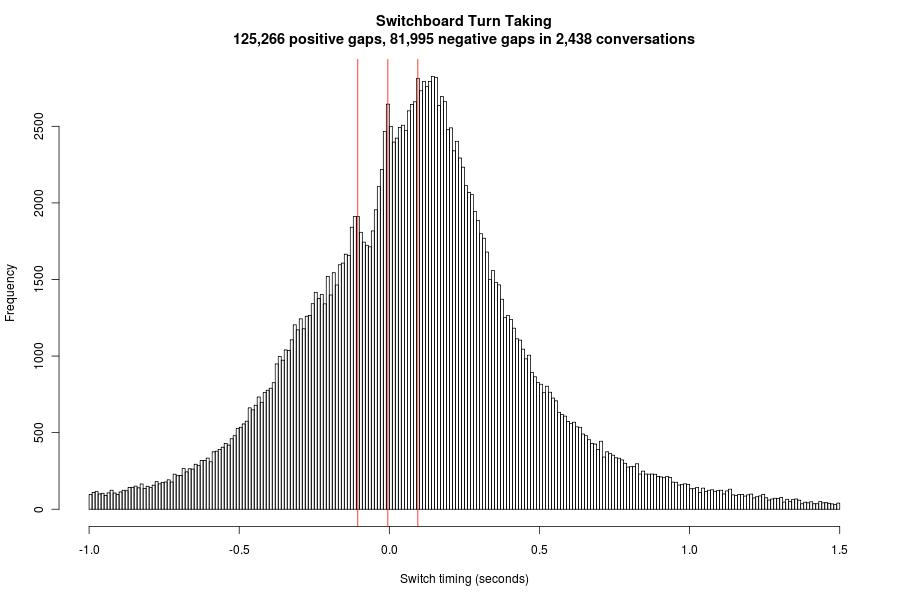

The (hand-checked) alignments indicate the start and end of all words, noises, and silences, for each speaker in each conversation. I counted all cases in which a speaker starts talking after the other speaker has been talking, either starting after the other speaker has stopped (yielding a positive offset equal to the silent gap), or before the other speaker has stopped (yielding a negative offset equal to the amount of overlap).

The result is a distribution in general agreement with Stivers et al. (although I'm looking at all speaker changes, not just answers to polar questions):

But the much larger dataset (about 2,000 times as many offset measurements) brings out some perhaps-interesting additional structure, especially an apparent increase in counts around -100 msec, 0 msec, and 100 msec (indicated by red vertical lines in the plot). This might be connected to the "periodic structure" postulated in Wilson & Zimmerman 1986 and Wilson & Wilson 2005, though they found conversation-specific differences in the time-structure suggesting that such effects might be washed out in a collective histogram of this sort.

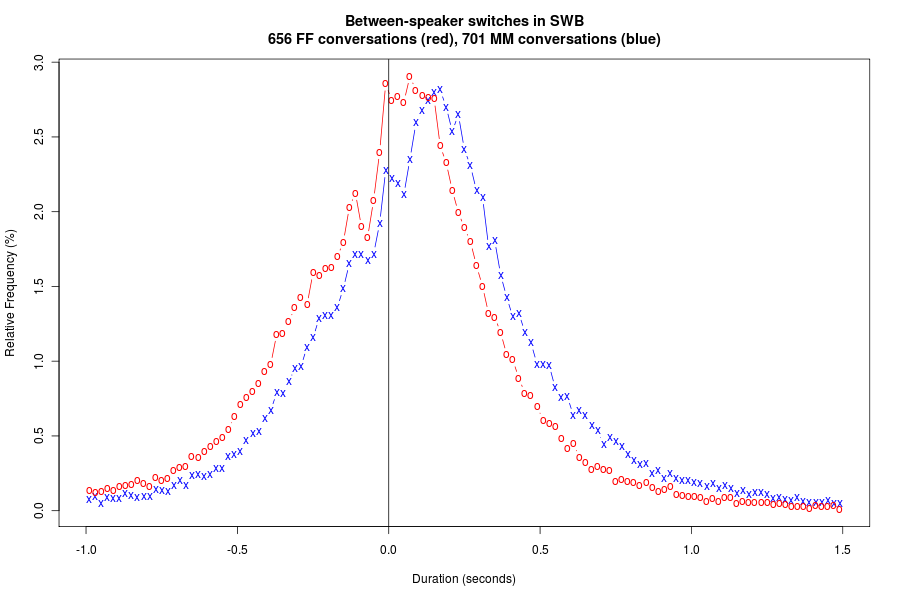

Since there's some demographic data available for the speakers in the SWB corpus, we can look at possible differences according to sex, age, years of education, geographical region, and so on. For this morning, I'll just take a look at speaker sex, and in particular whether there's any difference in speaker-change offsets between female/female and male/male conversations:

It's clear from the plot that overall, interactions in the FF conversations have shorter offsets than in the MM conversations. (FWIW, the median is 130 msec for the males vs. 30 msec for the females.) As usual, this raises more questions: Is this a difference across all types of interaction? Or are things different for "back-channel" responses vs. question-answer pairs vs. substantive comments? And what happens in mixed-sex conversations?

It might also be interesting to look at speaker age effects, regional effects, and so on. I've run out of time this morning — but isn't it fun to be able to do an interesting empirical investigation in an hour or so? And isn't it too bad that there's not more communication between the disciplines centered on conversational analysis and the disciplines centered on speech technology?

david said,

October 22, 2013 @ 12:03 pm

Thank-you for describing this interesting experiment.

The switchboard distributions are far less skewed than Stivers et al English distribution, although I see their Japanese and Korean and others are more symmetrical.

The peak at -100 could indicate a response time. In fast draw competition it took the fastest 145 msec to start to move after the light flash. It would be convenient if we could start to speak earlier.

Bill Benzon said,

October 22, 2013 @ 3:09 pm

This sort of thing gets really interesting when you consider what the brain has to do. Speaking involves muscles in the face and neck, which are close to the brain, but also muscles in the trunk, both abdomen and chest area, which are farther away. As Eric Lenneberg pointed out years ago in Biological Foundations of Language (1967?), the differences in neural conduction times over these distances are not negligible. Timing those signals so that everything works at out speech onset is tricky business. Perhaps that's one reason why mutual entrainment is helpful.

Rubrick said,

October 22, 2013 @ 3:16 pm

@myl: And isn't it too bad that there's not more communication between the disciplines centered on conversational analysis and the disciplines centered on speech technology?

Amen to that. Of all the concepts I desperately wish Siri understood, "interruption" is high on the list. When computers know to shut up when I'm talking — except in emergencies (which of course means they have to understand what constitutes such) — we'll have made some real progress.

Meg Wilson said,

October 22, 2013 @ 3:41 pm

Bill Benzon — Conversational partners' breathing entrains, particularly right around a turn transition (McFarland, 2001). This may help to get at least that part of the system in readiness.

McFarland, D. H. (2001). Respiratory markers of conversational interaction. Journal of Speech, Language, & Hearing Research, 44, 128-143.

AntC said,

October 22, 2013 @ 3:45 pm

Thank you Mark for shedding light from some hard data.

As you say, this ony raises more questions.

I'm particularly interested in the 'blips' in the graphs at around minus 100msec (more noticeable in FF turn-taking).

Does this suggest that the hearer 'knows' what the speaker is going to say; and 'knows' that they're about to finish; and has a response entrained? Or is it a case of the hearer interrupting the speaker so that the speaker stops abruptly?

[(myl) I think it's most likely to be people jumping in part-way through an utterance-final syllable. Reasons: (1) Final syllables are likely to be 300 msec or longer; (2) Reaction time is going to be longer than 100 msec.]

Perhaps the acoustic analysis could look at the cadence of the speaker?

There's a dozen research papers I can see already.

How to jazz it up enough to get funding, publication, and coverage in the popluar press? "It's true: women talking are more in tune."

Bill Benzon said,

October 22, 2013 @ 5:30 pm

@Meg Wilson: Thanks.

Nathan Myers said,

October 22, 2013 @ 6:25 pm

I wonder if telephone-system path-dependent signal delays, e.g. local vs. long-distance, can account for the timing quantification.

[(myl) These were all land-line calls collected in 1991, and I think that transmission delays should have been minimal and not very variable. However, I guess it's possible that the call-bridging setup somehow introduced an artifact.]

Tom Wilson said,

October 22, 2013 @ 6:50 pm

It seems to me that variability in the pace of speech looms as a major issue here. The fact of such variability, both across major sociocultural categories and across episodes within such categories, does not seem to be contested. What needs to be examined is whether, in view of this variability, aggregating data across episodes conceals important phenomena. Wilson & Zimmerman (1986) report data suggesting that this is the case.

With regard to AntC’s question concerning the hearer “knowing” what the speaker is going to say, the evidence is that the hearer depends on being able to project that the current turn in progress is heading to completion (Sacks et al., 1974, Schegloff, 2000), thus allowing him or her to set the speech-production apparatus in motion in advance of the completion point. This can result in turn transitions with very small gaps and also with very small overlaps. However, it’s one thing to know that a transition relevance place is coming up, and another to know precisely when to within hundredths of a second. The former requires the hearer to understand what the speaker is saying, while, according to Wilson & Wilson (2005), the latter depends on mechanistic entraining between the participants mediated by some signal embedded in the speech stream (possibly the rate of syllable production).

Sacks, H., Schegloff, E. A., & Jefferson, G. (1974). A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language, 50, 696-735.

Schegloff, E. A. (2000). Overlapping talk and the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language in Society, 29, 1-63.

Wilson, T. P., & Zimmerman, D. H. (1986). The structure of silence between turns in two-party conversation. Discourse Processes, 9, 375-390.

Wilson, M., & Wilson, T. P. (2005). An oscillator model of the timing of turn-taking. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 12, 957-968.

[(myl) Speaking rate clearly also varies during the course of a conversation, and even from phrase to phrase. So there seems to me to be an unsolved problem about how to study inter-speaker coordination empirically, since assuming a constant rate within "episodes" is just as false as assuming a constant across them.]

AntC said,

October 22, 2013 @ 7:58 pm

Thank you Mark and Tom,

An anecdote: Margaret Thatcher [British Prime Minister] was said to be able to dominate parliamentary question-time (its most notable feature being heckling) because she put her pauses for breath in the 'wrong' places and with the 'wrong' intonation. By the time the would-be hecklers realised that she'd stopped, she was talking again.

CherylT said,

October 23, 2013 @ 1:03 am

Thatcher was also reputed to use false sentence-final intonation in debates and when being questioned, to give others the impression she had finished an utterance. When her interlocutor then began to speak, she would continue, thereby giving the impression that the interlocutor had rudely interrupted. She would add to this with remarks ('If I may finish') that would typically follow an interruption, if memory serves.

Nick Enfield said,

October 23, 2013 @ 1:17 am

Here is the study on Thatcher:

Geoffrey W. Beattie, Anne Cutler, & Mark Pearson. 1982. "Why is Mrs Thatcher interrupted so often?" Nature 300, 744 – 747 (23 December 1982); doi:10.1038/300744a0

Bob Ladd said,

October 23, 2013 @ 1:23 am

A study of Mrs. Thatcher's conversational style was published in Nature way back when. A pdf is here. (I used to use this material in Linguistics 1 lectures until the students stopped being sure who Mrs. Thatcher was.)

Bill Benzon said,

October 23, 2013 @ 2:02 am

In view of this conversation I've just bumped an old post to the top of the stack over at New Savanna (Jabba the Hut, or How We Communicate). It's about conversation, but takes as its point of departure something that's rather different. I open the post with these old notes:

And so with conversation as well, at least to some extent.

Tom Wilson said,

October 23, 2013 @ 9:25 am

Mark correctly notes that the pace of talk also varies over the course of a single conversation. Wilson & Zimmerman (1986, p. 389) discuss this issue, treating it as a source of measurement error that should work against finding a periodic pattern in the durations of silences, and suggesting that an area for further research is to develop a way to normalize measurements of duration relative to pace. Although the fact that they did find significant results indicates that the effect of this variability is not strong enough to obscure the phenomenon, this does remain an open problem.

Jeb said,

October 23, 2013 @ 3:39 pm

Tom. Hesitant to comment as I am not familiar with this from an academic perspective but a performance one and I don't think making comparison is always successful here as seems to be a tendency to generalize and you view the process from a working perspective that's different and subject to a range of different factors.

You're comments on the hearer knowing and small transition gaps did fit in rather well with a particular form of drama I have some limited experience with (two handed comedy) and I could adopt you're words with ease if I wanted to describe the processes and issues you are working through.

A different style I have more familiarity with, Declamatory style of acting. One of the technical features is that you end you're inflection high at the end of a sentence. This is contrary to natural speech patterns (or certainly in my cultural neck of the woods where the high point of inflection is at the start of a sentence) its also extremely hard to do as its so counter intuitive. Was highly valued in the theater as to do it well is considered to be a mark of ability and skill, given the difficulty involved but its novelty also works well on the intended target.

Jeb said,

October 23, 2013 @ 6:40 pm

i.e. we were trained to understand that with inflection in natural speech it tends in a sentence hit a high inflection point towards the start and ends low (speculating it may signal something).

Tom Wilson said,

October 24, 2013 @ 10:35 am

Jeb-

There's a literature on cues that regulate turn-taking: see Wilson & Wilson (2005, pp. 960-961) for discussion and references.

Ron said,

October 24, 2013 @ 12:08 pm

Strapping on my special thin ice skates here, but @AntC's comment made me wonder about two things: First, is there a relationship between overlap or gap and how much complexity of structure or meaning tends to occur at or near the end of an utterance? Perhaps a person who hears an utterance in such a language might need more time to process all the content near the end and might not be able to jump in right away with a response.

I also wonder about languages set up the other way, where the end of an utterance may be light on complexity but contains cues (a) that the utterance is about to end; or (b) that the utterance is, say, interrogative, negative, emphatic, etc. (especially if said cues also tend to mark the end of an utterance).

Recalling my thin ice caveat above, this post made me think about German, which (IIRC) back end loads a lot of meaning in a sentence, and Japanese, which may end sentences with particles that mark, say, emphasis, but often are heard at the tend of a sentence.

Anything there potentially, or totally off base?

PS – "[I]sn't it fun to be able to do an interesting empirical investigation in an hour or so?" Damn right, and I'm jealous.

[(myl) For some comparisons across languages, see Jiahong Yuan, Mark Liberman, and Chris Cieri, "Towards an integrated understanding of speech overlaps in conversation", ICPhS 2007:

We investigate factors that affect speech overlaps in conversation, using large corpora of conversational telephone speech. We analyzed two types of speech overlaps: 1. One side takes over the turn before the other side finishes (turn-taking type); 2. One side speaks in the middle of the other side’s turn (backchannel type). We found that Japanese conversations have more short turn-taking type of overlap segments than the other languages. In general, females make more speech overlaps of both types than males; and both males and females make more overlaps when talking to females than talking to males. People make fewer overlaps when talking with strangers than talking with familiars, and the frequency of speech overlaps is significantly affected by conversation topics. Finally, the two conversation sides are highly correlated on their frequencies of using turn-taking type of overlaps but not backchannel type.

]

Jeb said,

October 24, 2013 @ 3:23 pm

"There's a literature on cues that regulate turn-taking"

Thanks, I had already caught the references and have marked them down for 'translation' (the fragmentary world of knowledge) when I can find time to give the subject some attention. I was tempted at first to ignore the material and indeed L.L. as despite some understanding of this issue from a different perspective I could not decipher the language to any degree, which was somewhat disconcerting.

You're comment was most helpful as it took no effort to understand and applied directly and fully to experience.

Unfortunately I can't provide citation and verification for my source, these things are orally transmitted, very traditional form of learning.

Bill Benzon said,

October 25, 2013 @ 3:18 am

That cross-cultural tidbit is fascinating, Mark. What languages other than Japanese were used? One could conjecture that tight overlaps are an index of familiarity, hence your stranger vs. familiars observation. As for the Japanese vs. the rest, are we looking at the long-term effects of cultural homogeneity?