"Lost" languages?

« previous post | next post »

The use of the word lost in this recent story caught my attention — Pankaj Doval, "Google set to revive lost Indian languages", The Times of India 10/3/2024:

As it gets deeper into India with generative AI platform Gemini and other suite of digital offerings, Google has taken up a new task in hand – reviving some of the lost Indian languages and creating digital records and online footprint for them.

I'll say more later about Google's important and interesting contribution to an important and interesting problem. But first, what does the article mean by "lost Indian languages"? I started from the idea that languages that are "lost" are extinct, i.e. no longer spoken — and a web search for the phrase "lost languages" confirms that others have the same interpretation.

However, the Times of India article makes it clear that this is not what they mean:

The idea is to enable people to easily carry out voice or text searches in their local dialects and languages.

As the work moves towards completion, people in the hinterland and various regions can easily do voice search in their own languages to gain accurate and valuable information from, say, Google's Gemini AI platform or carry out live translations, harness YouTube better to target their communities.

The project has so far reached 59 Indian languages, including 15 that currently do not have any kind of a digital footprint and were rather declining in usage.

The project has so far reached 59 Indian languages, including 15 that currently do not have any kind of a digital footprint and were rather declining in usage.

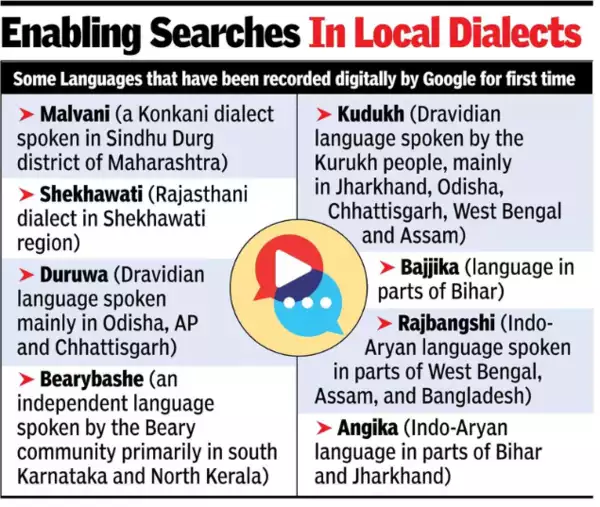

And the article includes this graphic, listing 8 of those 59 languages:

Looking these languages up on Ethnologue and Wikipedia tells us that some of them have as many as 10 to 20 million speakers (details below), so they're far from extinct. And it's misleading to say that they "have been recorded digitally by Google for first time" — for example, the Wikipedia article for Bajjika says that "Lakshmi Elthin Hammar Angna (2009) was the first formal feature film in Bajjika. Sajan Aiha Doli le ke came after that". And YouTube has quite a few items partly or entirely in Bajjika, including a Bajjika Channel.

Of course, some of the cited languages are smaller — thus Wikipedia says that Duruwa has 18,151 speakers, while Ethnologue give the number as 12,000. And the motivation for the Google project is that all of these languages are (or were) "under documented" or "under resourced", in the sense that they lack the digital resources needed for robust modern language technologies such as speech-to-text, text-to-speech, text understanding, and so on. And there's a general concern that this situation makes language potentially "endangered" and thus at risk of being lost.

It's possible that Indian English generally uses "lost language" in this sense, though I'm guessing that the author of the article (or someone else in the editorial chain) made the choice.

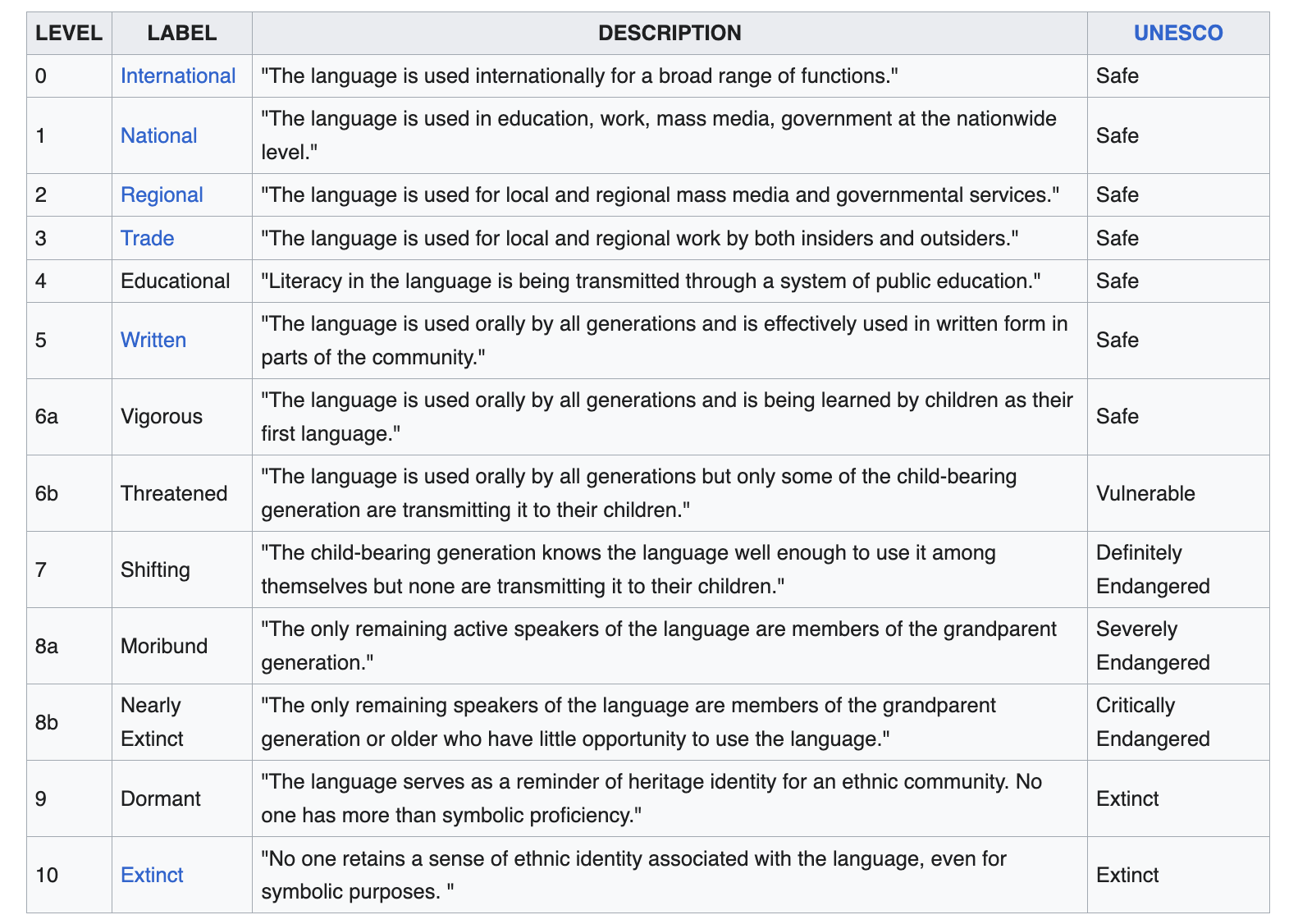

Anyhow, it's worth spending a few minutes on a widely-used attempt to clarify the relevant terminology — the Expanded Graded Intergenerational Disruption Scale (EGIDS), originally proposed in M. Paul Lewis and Gary Simons, "Assessing endangerment: expanding Fishman’s GIDS" (2010):

ABSTRACT: Fishman’s 8-level Graded Intergenerational Disruption Scale (GIDS) has served as the seminal and best-known evaluative framework of language endangerment for nearly two decades. It has provided the theoretical underpinnings for most practitioners of language revitalization. More recently, UNESCO has developed a 6-level scale of endangerment. Ethnologue uses yet another set of five categories to characterize language vitality. In this paper, these three evaluative systems are aligned to form an amplified and elaborated evaluative scale of 13 levels, the E(xpanded) GIDS. Any known language, including those languages for which there are no longer speakers, can be categorized by using the resulting scale (unlike the GIDS). A language can be evaluated in terms of the EGIDS by answering five key questions regarding the identity function, vehicularity, state of intergenerational language transmission, literacy acquisition status, and a societal profile of generational language use. With only minor modification the EGIDS can also be applied to languages which are being revitalized.

Here's the EGIDS table from the Wikipedia article:

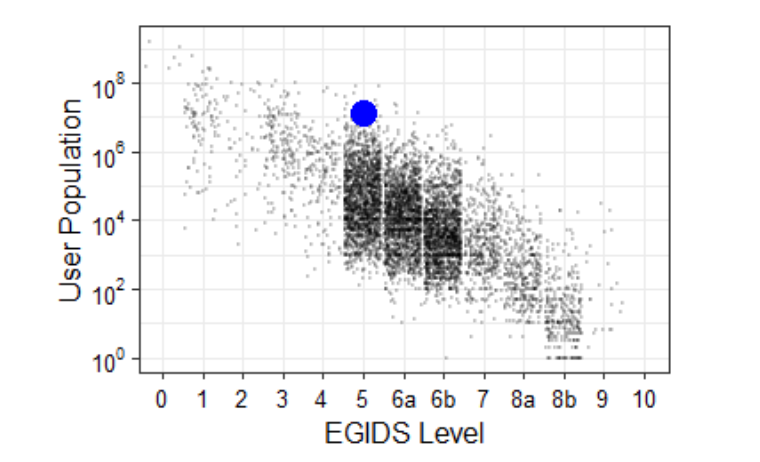

The current edition of Ethnologue offers a "Language Cloud" for each language, consisting of a scatter plot whose x-axis is the EGIDS level, and whose y-axis is the estimated number of speakers. Here's the Language Cloud for Bajjika:

Ethnologue's explanation of their dot colors:

- Purple = Institutional (EGIDS 0-4) — The language has been developed to the point that it is used and sustained by institutions beyond the home and community.

- Blue = Developing (EGIDS 5) — The language is in vigorous use, with literature in a standardized form being used by some though this is not yet widespread or sustainable.

- Green = Vigorous (EGIDS 6a) — The language is unstandardized and in vigorous use among all generations.

- Yellow = In trouble (EGIDS 6b-7) — Intergenerational transmission is in the process of being broken, but the child-bearing generation can still use the language so it is possible that revitalization efforts could restore transmission of the language in the home.

- Red = Dying (EGIDS 8a-9) — The only fluent users (if any) are older than child-bearing age, so it is too late to restore natural intergenerational transmission through the home; a mechanism outside the home would need to be developed.

- Black = Extinct (EGIDS 10) — The language has fallen completely out of use and no one retains a sense of ethnic identity associated with the language.

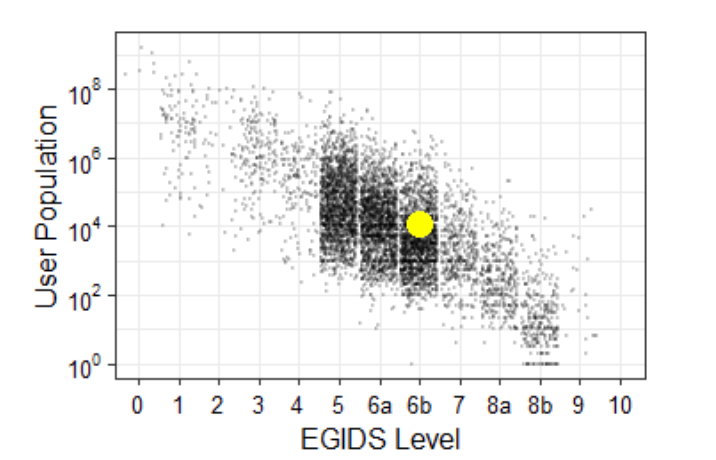

Ethnologue's Language Cloud for Duruwa uses a yellow dot:

I believe that Google's work on under-documented languages of India has been led by Partha Talukdar, whose LinkedIn page says "I lead the Languages group at Google DeepMind, India focusing on making LLMs work well for speakers of more number of languages. The goal is to make sure benefits of AI are available to a broader population where language is not a barrier anymore."

One of his group's relevant contributions is "IndicGenBench: A Multilingual Benchmark to Evaluate Generation Capabilities of LLMs on Indic Languages":

As large language models (LLMs) see increasing adoption across the globe, it is imperative for LLMs to be representative of the linguistic diversity of the world. India is a linguistically diverse country of 1.4 Billion people. To facilitate research on multilingual LLM evaluation, we release IndicGenBench – the largest benchmark for evaluating LLMs on user-facing generation tasks across a diverse set 29 of Indic languages covering 13 scripts and 4 language families. IndicGenBench is composed of diverse generation tasks like cross-lingual summarization, machine translation, and cross-lingual question answering. IndicGenBench extends existing benchmarks to many Indic languages through human curation providing multi-way parallel evaluation data for many under-represented Indic languages for the first time. We evaluate a wide range of proprietary and open-source LLMs including GPT-3.5, GPT-4, PaLM-2, mT5, Gemma, BLOOM and LLaMA on IndicGenBench in a variety of settings. The largest PaLM-2 models performs the best on most tasks, however, there is a significant performance gap in all languages compared to English showing that further research is needed for the development of more inclusive multilingual language models.

Chas Belov said,

October 6, 2024 @ 5:04 pm

Ah, thank you for the link. When I went to the Bajjika Channel, I found a video of multiple Bajjika music videos. The second song thoughtfully included the title in the visible frame, and I was able to find Govind Bolo Hari Gopal Bolo (12 minute version; I see there are much longer versions available by different artists) in YouTube music and add it to my global candidate Incubator playlist.

Curious to see if Google Translate knew about Bajjika, I copied the title into Google Translate. It identified "Govind Bolo Hari Gopal Bolo" as being in Slovak, and translated it into English as the same.

Further, it sounds to my English-language ears like they are singing Govinda Bolo Hari Gopala Bolo.

Alternative text for the list of languages image:

Enabling Searches In Local Dialects.

Some Languages that have been recorded digitally by Google for first time.

Malvani (a Konkani dialect spoken in Sindhu Durg district of Maharashtra).

Shekhawati (Rajasthani dialect in Shekhawati region).

Duruwa (Dravidian language spoken mainly in Odisha, AP and Chhattisgarh).

Bearybashe (an independent language spoken by the Beary community primarily in south Karnataka and North Kerala).

Kudukh (Dravidian language spoken by the Kurukh people, mainly in Jharkhand, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, West Bengal and Assam).

Bajjika (language in parts of Bihar) Rajbangshi (Indo-Aryan language spoken in parts of West Bengal, Assam, and Bangladesh).

Angika (Indo-Aryan language in parts of Bihar and Jharkhand)

Chas Belov said,

October 6, 2024 @ 5:08 pm

And I love the new feature where it shows me that my comment is waiting to be approved rather than just disappearing and making me think something is broken. (If this comment seems to be coming out of nowhere, then my previous comment hasn't been approved (yet).)

Chas Belov said,

October 6, 2024 @ 5:16 pm

Technically, it doesn't show me on the page that it's unapproved, and that would be a nice improvement, but it does have an "unapproved" parameter in the URL, by which I was able to suss out that there would be a delay until you can check it out.

Lars said,

October 6, 2024 @ 5:58 pm

As I'm sure you know, the original aim of Unicode was that all people on Earth should be able to type their names on a computer. But then, Unicode broadened their scope with emojis. The merits of this move are debatable; while it may have given more Americans an incentive to adopt Unicode, there was opposition from speakers of minority languages (I remember one article written by an Indian, but I can't give a reference just now). They felt that the focus had shifted too much. I guess you could call those missing languages "lost".

David Marjanović said,

October 6, 2024 @ 6:25 pm

As far as I understand, Unicode has managed to walk and chew gum pretty well at the same time.

Rick Rubenstein said,

October 6, 2024 @ 10:22 pm

Perhaps they meant "Lost" in the sense of the TV show. Are these languages utterly baffling and become only more so over time? ;-)

Ebenezer Scrooge said,

October 7, 2024 @ 2:16 am

Indian journalistic English often reminds me of Victorian journalistic English. But "lost language" still does not compute.

AG said,

October 7, 2024 @ 7:31 am

Not to oversimplify an interesting investigation, but I think the article explains what they meant by "lost languages" with the above-quoted phrase "including 15 that currently do not have any kind of a digital footprint". They're lost in the sense that a language without a digital footprint is virtually nonexistent (terrible pun intended).

Monali said,

October 7, 2024 @ 11:51 am

I think the writer does not understand what is meant by "lost languages". To say "lost languages" is clearly "extinct languages". It could have been written better as "languages lost in the world of technology" or something like that. The writer was either simply casual or deliberately wanted attention.

maidhc said,

October 8, 2024 @ 3:40 am

Some time ago (maybe 7 or 8 years ago) I attended a presentation by a high-up researcher from Google about all the wonderful things Google was doing. At the end there was a question period, but nobody asked a question, so I jumped in. I quoted a presentation I had heard just before at that time, which I can't remember exactly what it was any more, to the effect "<famous language expert> says that half of the languages spoken today will be extinct by the end of the century, and is Google doing anything to address this?"

He answered that Google indeed had ongoing efforts to provide support for endangered languages. So I guess this is an example of that.