More problems

« previous post | next post »

Following up on J.D. Vance's reduced pronunciation of "problems", I looked through a 100-instance random sample of that word in real-life contexts, taken from the 23,147 phrases containing it in the previously-described NPR podcast corpus. About half of those examples exhibit lenition of the medial /bl/ consonant cluster, to the point where its IPA transcription would need to change, often all the way to deletion. This pattern follows the general treatment in American English of intervocalic consonant sequences that are not followed by a stressed vowel within the same word.

One of the examples is especially interesting. In a passage from All Things Considered (11/16/2012), the word "problems" occurs twice in the same phrase, in the middle of a discussion of Bengazi and the resignation of David Petraeus (at around 6:30.58 in the audio):

CORNISH: He argued that they struck it from the transcripts so as not to tip off terrorist groups that the intelligence community was on to them. But E.J.?

DIONNE: I'm not feeling quite so French as David is. I think, boy, did you open up – did these various activities and affairs not only on the part of Petraeus open up a real series of problems, you also have problems raised with the FBI, the shirtless FBI agent, and did – what in the world was his role in this? So I think the whole thing is very unfortunate.

In terms of Bengazi […]

[Since this is Language Log, not Scandals-Of-Yore Log, you'll need to read or listen to the podcast to remind yourself of the surrounding story line(s).]

Here's the phrasal context for the two versions of "problems":

[…] of problems.

You also have problems raised with the FBI, the shirtless uh FBI […]

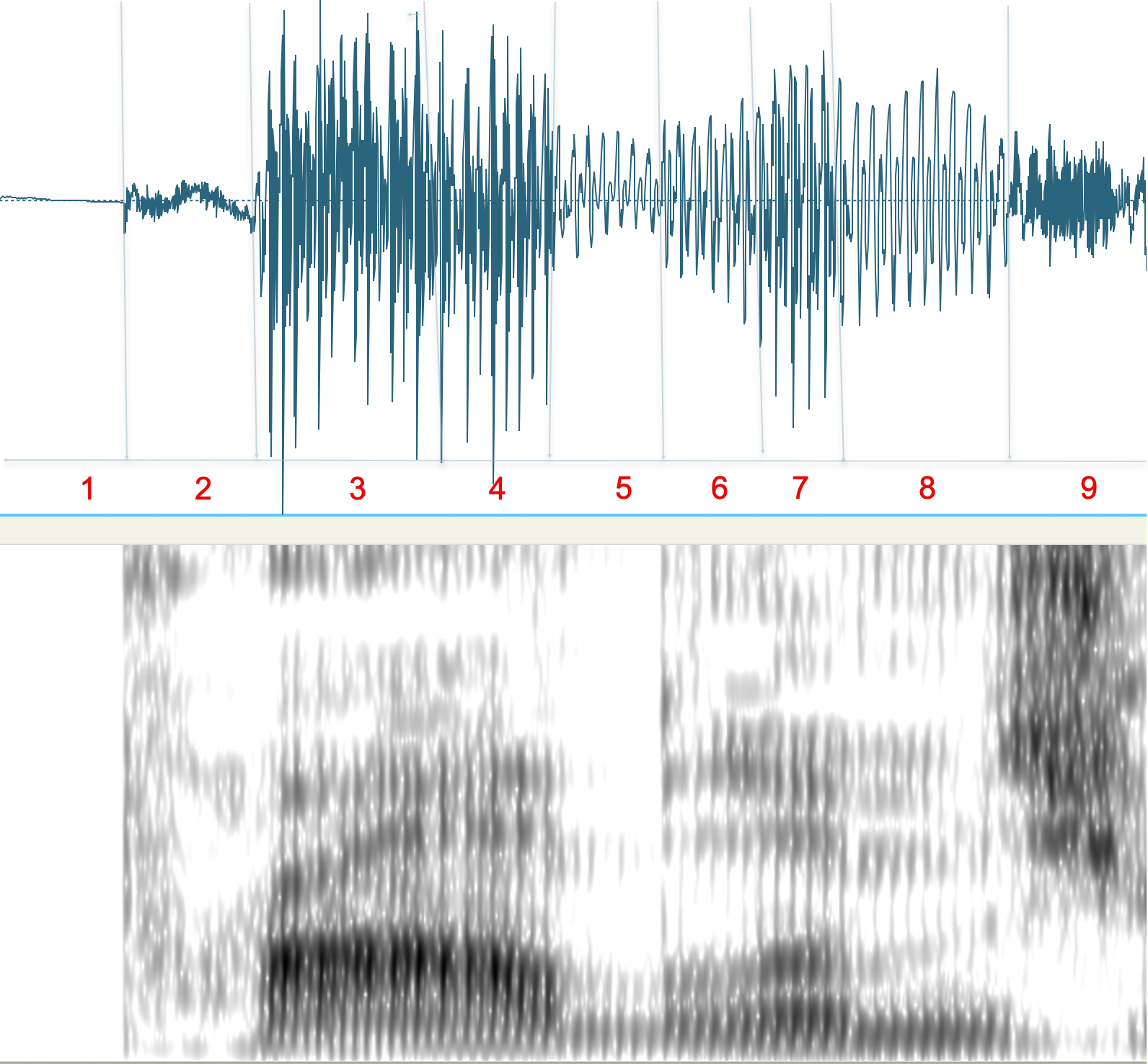

The first pronunciation of "problems" is pretty much the dictionary version:

Although of course all the articulations are overlapped, we can point to time-regions corresponding to traditional phonetic segments:

- [p] closure

- [p] release and aspiration

- [ɹ] transition into the stressed [ɐ] vowel

- the [ɐ] vowel

- the [b] closure

- [b] release into the [l]

- reduced [ə]-like vowel

- [m] nasal murmur

- [z] frication

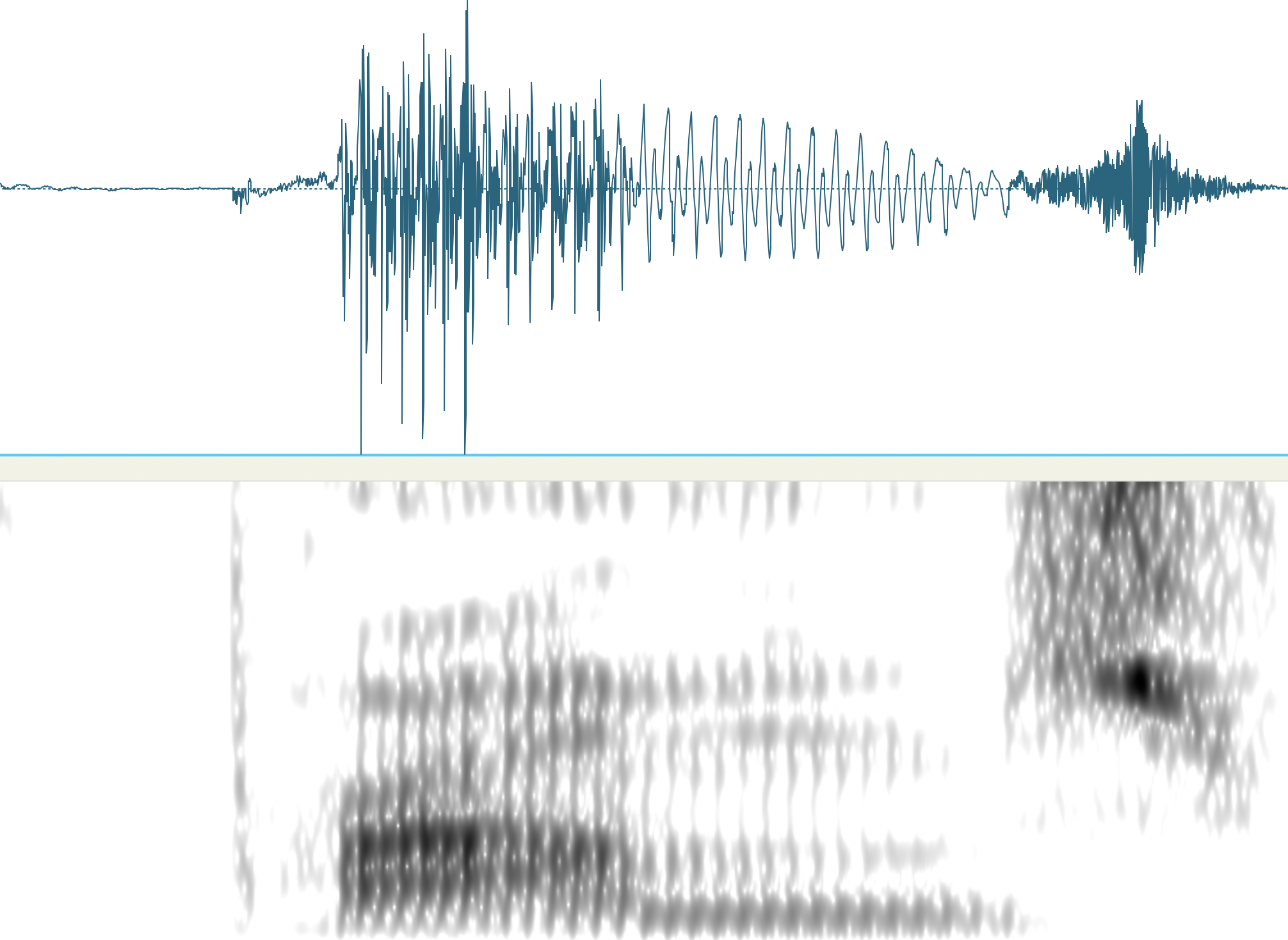

But the second version of "problems" is phonetically rather different:

An IPA approximation would be something like [ˈpɹɐmz], though as usual there's more going on than the symbol-sequence suggests.

Why the difference? There are at least two relevant factors:

- The first "problems" is phrase-final, and therefore pronounced in a longer and more leisurely way;

- The second "problems" is shorter not only because it's phrase-medial, but also because it's a repetition of a recently-used word (see e.g. Fowler 1988).

We should also note that E.J. Dionne's turn shows the same sort of false starts and rapid repetitions that the earlier post observed in J.D. Vance's speech:

I'm not feeling quite so French as David is.

I- I think, boy, did you open up a-

did- did these

various activities and affairs not only

on the part of Petraeus open up a real series

of problems, you also have problems raised with the FBI, the shirtless uh FBI

agent, and did-

what- what w- in the world was his role in this? So

I- I think the whole thing is very unfortunate.

Cervantes said,

August 18, 2024 @ 11:04 am

Since Dionne is an inveterate talker on the radio, I would say his pronunciation is relatively precise. I definitely hear the "b" both times, although maybe not as crisply the second time. I don't think professional radio talkers are exemplars of vernacular speech. I have hundreds of recordings of physician visits, featuring real people, and it really doesn't sound the same.

Mark Liberman said,

August 18, 2024 @ 11:34 am

@Cervantes: " I don't think professional radio talkers are exemplars of vernacular speech."

Maybe, but my experience is that they talk pretty much like other people in semi-formal but spontaneous-speech contexts. Anyhow, Dionne is speaking American English, and exhibiting reduction phenomena that have never been studied or even mentioned by linguists. So if non-pros are even further away from the dictionary, we're in bigger trouble.

Y said,

August 18, 2024 @ 1:14 pm

For the second version, you say, "An IPA approximation would be something like [ˈpɹɐmz]".

How about [ˈpɹɐ.m̩z]?

Cervantes said,

August 18, 2024 @ 2:22 pm

"reduction phenomena that have never been studied or even mentioned by linguists?" Hardly.

Mark Liberman said,

August 18, 2024 @ 3:41 pm

@Cervantes:

Many reduction phenomena in English have been studied — but most have not been. And in particular, the lenition/deletion of intervocalic /bl/, as in "problems", has not been discussed, as far as I know. In particular, it is not noted or even hinted at in the rather short and informal link that you sent. Can you point to any actually relevant coverage?

Cervantes said,

August 18, 2024 @ 4:11 pm

It would be impossible, and as far as I can see pointless, to specifically study every possible lentition/elision, word by word. I will concede that it is unlikely anyone has specifically published on the elision/lentition of the "b" in "problem." I doubt you can find a specific reference to the "c" in "rectification" or the first "t" in "antidisestablishmentarianism," but what would be the point? The typical English speaker's vocabulary is 20,000 to 30,000 words. Should linguists study specifically how people pronounce each one of them?

Yves Rehbein said,

August 18, 2024 @ 4:50 pm

The dark spot in the second bulge of the wave of the second snippet, that's where the b is coarticulated in the middle of the m, isn't it? It's also vissible in the first snippet. So you have one problimps and 99 prolmbs but the pitch aint one. Hit me.

J.W. Brewer said,

August 18, 2024 @ 5:11 pm

E.J. Dionne was and is primarily known for being a "print" journalist and was already an established name in that field before he became a regular (I assume?) guest on NPR talk shows. It is thus comparatively likely that he never went through the process of self-consciously learning how to talk on air that many people interested in a radio career go through. Some with such aspirations have also worked on losing a marked regional/class accent perceived as a career hindrance, but that's a different project from learning how to speak in what seems like a natural conversational tone to an audience you can't see while avoiding pauses that don't seem unduly long in face-to-face interaction but can be the dreaded "dead air" in a radio context. This is a learnable skill, but not one you are likely to already have, pretty much regardless of accent or dialect. Even old-time elocution lessons probably wouldn't have given you the dead-air avoidance aspect of it. In a talk-show context where multiple people are conversing with each other in real time in the studio rather than just one person at the mike engaging in one-way discourse with the invisible audience outside the studio, this may be less important.

I was thinking about this just the other day because the latest radio news in the NYC market is that WCBS-AM is abandoning its all-news format after many decades, which reminded me that when I was a trainee aspiring to become a cool DJ at my college radio station over 40 years ago, the training director told us all to listen to WCBS even if we had no interest in doing newscasts: this because the on-air staff there were such exemplary models of how to talk effectively on-air without it sounding like they were doing something unnatural or self-conscious. (A detail of interest to phonologists from this training might be that our station used cheap enough microphones that we needed to learn not to have our mouths too close to the mike when uttering word-initial aspirated consonants, to avoid an unpleasant-sounding result called "popping your P's.")

Mark Liberman said,

August 18, 2024 @ 5:32 pm

@Cervantes: "It would be impossible, and as far as I can see pointless, to specifically study every possible lentition/elision, word by word."

A central goal of scientific linguistics is to model/describe/predict the various pronunciation patterns of a language, based on a theory of lexical representations and their phonetic interpretation in context. This has been true since Pāṇini several millennia ago. My point is that recent theories about English pronunciation fail to take account of many relevant patterns. You obviously don't care, and that's fine, but please don't assume that your ignorance should be everyone else's bliss.

JPL said,

August 18, 2024 @ 6:19 pm

@Cervantes:

Yes, when I read your comment I laughed and said to myself, "That's what you think!" But for someone interested in the relation between the dynamics of articulation and, e.g., the structure of citation forms of lexemes, or problems of historical sound change, certain phonological contexts raise interesting puzzles and require explanation. The theory captures our present understanding of these phenomena. Phonologists and phoneticians will pursue those kinds of cases, but nobody is going to say, "I'm going to make an exhaustive inventory of all possible context-driven changes in pronunciations of a citation form". There is a reason why this particular one is interesting.

Chris Button said,

August 18, 2024 @ 9:38 pm

I don't think the problem is with the IPA per se. You can play around with the diacritics to get what you need. Rather it's with the basic analytical starting point, which should always be the syllable. It's Peter Ladefoged's "phonemic conspiracy".

The broad/narrow or phonemic/phonetic notations of /…/ and […] often confuse as much as elucidate. Y.R. Chao captured it all those years ago just with the title of his piece: "The Non-Uniqueness of Phonemic Solutions of Phonetic Systems."

JPL said,

August 19, 2024 @ 1:18 am

I don't think you can say that the second version is two syllables, but there does seem to be a "ghost of two syllables", in that there seems to be a movement of the tongue between the two vowel positions that the full form would have. Put together, the vowel segment seems shorter than if there were one syllable with a medial glide, since here the distance between the two points is minimal. The intended word is quite predictable in that context, so you don't need much to disambiguate it. Initial and final consonantal segments and the stressed vowel even without the glide would be sufficient.

Mark Liberman said,

August 19, 2024 @ 6:40 am

@JPL: "I don't think you can say that the second version is two syllables, but there does seem to be a "ghost of two syllables", in that there seems to be a movement of the tongue between the two vowel positions that the full form would have."

Three points:

1. Yes.

2. This is a general feature of English, related to the general role of "foot" (beyond syllable) structure in the language.

3. And it's also connected to the theoretical difference between treating allophony as the contextual re-writing of symbol strings, and treating allophony as the contextual interpretation of symbol strings as articulation and sound.

Cervantes said,

August 19, 2024 @ 7:10 am

Sorry, but I don't see why there's anything particularly interesting or novel to be learned by focusing on the reduction of the b in problem. That seems to me a perfectly ordinary and well known phenomenon. To claim that this is a phenomenon that has "never been studied or even mentioned by linguists" strikes me as completely ridiculous. Yes, I suppose you wouldn't find a published paper that specifically mentions the b in problem but I'm completely baffled by what you think is instructive about this particular example.

Mark Liberman said,

August 19, 2024 @ 7:21 am

@Cervantes: " I don't see why there's anything particularly interesting or novel to be learned by focusing on the reduction of the b in problem.":

The answer depends on understanding the relationship between facts and theories in science, a topic that clearly doesn't interest you.

Chris Button said,

August 19, 2024 @ 2:26 pm

I'm with Cervantes here. And the question asked by Cervantes seems to demonstrate genuine interest in the topic rather than any lack of interest.

The discussion here seems too focused on the inadequacies of segmental representations while blissfully ignoring the elephant in the room: How do you account for the syllable as a phonetician or phonologist trained in a sacrosanct distinction between consonants and vowels? Just think how much better our linguistic analyses might be if the alphabet had never been invented and syllabic analyses dominated our approaches.

A theoretical phonological analysis can kill the notion of vowels off entirely in languages depending on how deep/theoretical the analyses (and the phonemes in all their "non-uniqueness") go. A phonetic analysis can't do that because it relies on an articulatory definition of what constitutes a vowel, but it can recognize that the whole abstract dichotomy is very blurry when looked at from the perspective of a syllable.

Bob Ladd said,

August 19, 2024 @ 4:30 pm

Chris Button:

I don't see how the syllable helps with the problem that MYL is talking about. The trouble with any symbolic representation of actual utterances is that the speech signal isn't naturally segmentable into symbol-sized chunks. MYL's examples have focused on specific /b/'s and /l/'s and so forth, but you have the same theoretical and conceptual problem if your symbolic representation is a string of syllables rather than a string of Cs and Vs. The discussion in the thread of whether the reduced token of "problem" is one syllable or two shows that the syllable has the same problems as IPA-style segments. Segments and syllables are useful abstractions for phonology, but they are abstractions, and (here I agree with MYL) it's not clear that they are useful elements of an accurate and complete physical description of speech signals.

RfP said,

August 19, 2024 @ 4:40 pm

@Cervantes

I’m an author, not a scientist, but from my at times quite passionate and exhaustive brushes with science, I can only conclude that it’s often a bit like an “American-style” adventure story, as described here by screenwriting instructor Robert McKee:

– The Real McKee:

Lessons of a screenwriting guru, Ian Parker, The New Yorker, October 12, 2003

For some scientists, these “insignificant puzzles” are of great interest in and of themselves—and then there’s the times when they rip the veil away.

RfP said,

August 19, 2024 @ 4:42 pm

Apologies for the mangled HTML. The article I mentioned is at https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2003/10/20/the-real-mckee.

RfP said,

August 19, 2024 @ 5:25 pm

@Cervantes

And then again, there was some guy–his name escapes me–who was really into tilting at windmills.

I don’t imagine he ever amounted to much. You would seem to agree.

Chris Button said,

August 19, 2024 @ 6:34 pm

@ Bob Ladd

Totally valid point. However, the syllable is intuitive (depsite discussions of where it may start and begin) whereas strings of Cs and Vs are entirely abstract, open to interpretation, and learned.

Chris Button said,

August 19, 2024 @ 9:51 pm

"Hear" could be interpreted as two syllables by an American and a Brit (regardless of what they have learned in school or the spelling) who agree on the analysis. "Hearing" could then provoke a debate between an American and a Brit over whether it is two or three syllables.

I'm not really sure what is new in this discussion in that regard.

Although, it's probably worth pointing out that it is perhaps better phrased as moras rather than syllables. Which is why the beat of a Japanese haiku is invariably wrong in English because people translate them using syllabic beats instead of moraic beats.

Regardless, it's that underlying shwa in "nea" and the other underlying schwa in "r". Everything else is dancing around those two schwas and coloring them while bumping at the edges.

I think IPA symbols with all their diacritics and super/sub-scripts can handle an analysis however narrow or broad. But the point is that the analysis should all perhaps be centered on the underlying (or overt) schwa (aka syllable or mora) rather than linearly across it segment by segment.

Matt Juge said,

August 20, 2024 @ 12:18 pm

118 elements? We have to figure out how they all work?