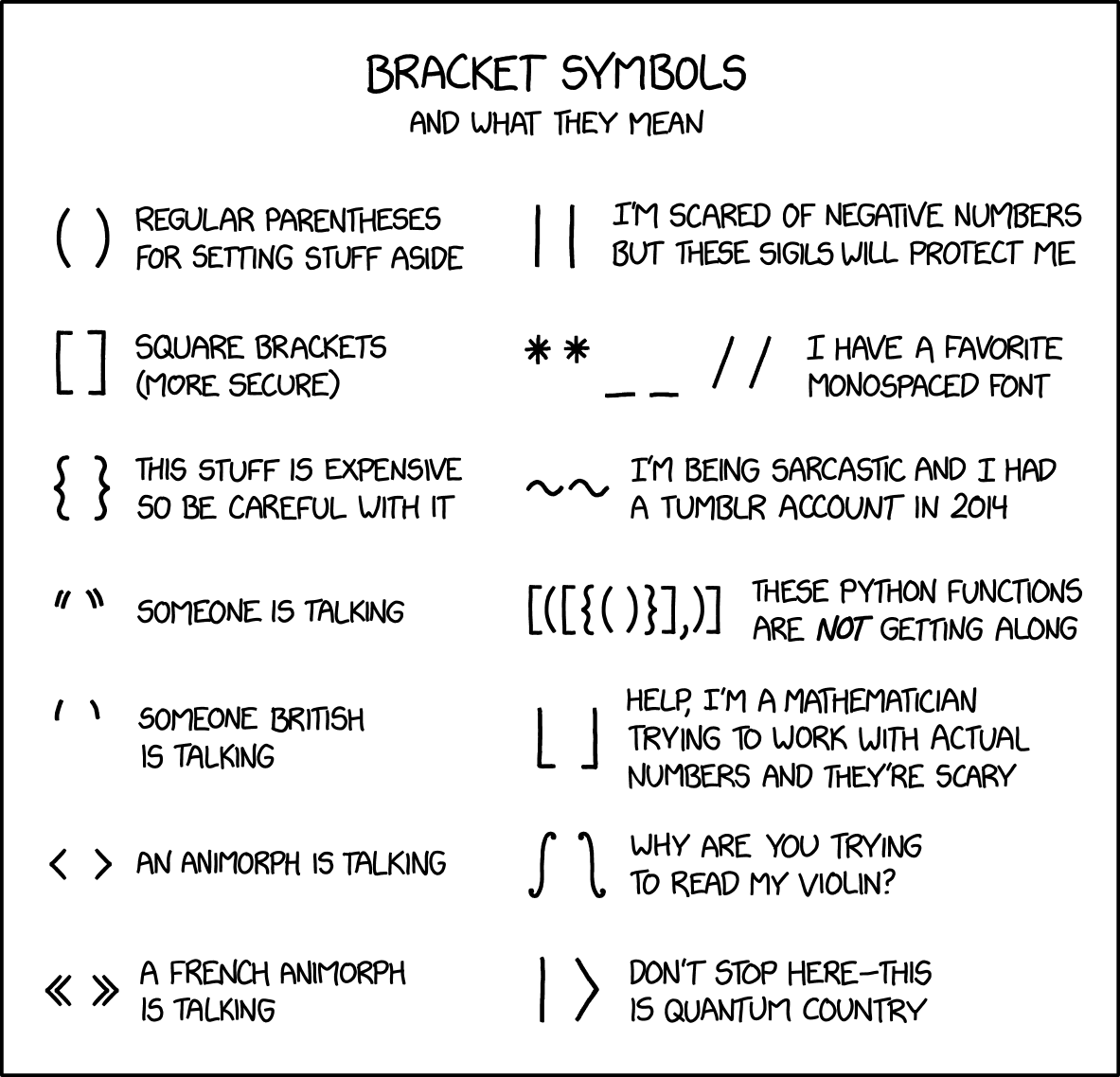

The meaning of bracket symbols

« previous post | next post »

Left out: the IPA's convention that slashes are used for strings representing abstract phonemic symbol sequences, while square brackets are used for strings representing instances (or types) of phonetic performance, e.g.

'tenth' /tɛnθ/ [tʰɛ̃n̪θ]

The distinction is sometimes called "broad" vs. "narrow" transcription, which of course allows for indefinitely many gradations of breadth.

To the extent that there's a genuine conceptual difference, it's the idea that

- the phonological system of a given (variety of a) language makes a limited number of qualitative symbolic distinctions in the lexical representation of word pronunciations, so that information about the claims that a given word makes on sound can be represented by an IPA string (leaving out many issues such as syllable (sub-)structure, underspecification, super- or auto-segmental organization,, etc.);

- In contrast, a specific articulatory and acoustic performance of a given word involves gradient variation, which can be (very crudely) described using more elaborate IPA strings.

See "Towards Progress in Theories of Language Sound Structure", 2018.

Also "On beyond the (International Phonetic) Alphabet", 4/19/2018; "Farther on beyond the IPA", 1/18/2020.

Garrett Wollman said,

July 5, 2024 @ 12:41 pm

Randall also missed ,,someone German is talking".

Thomas said,

July 5, 2024 @ 1:45 pm

I might add: »Someone German is talking in a book«

DJL said,

July 5, 2024 @ 2:52 pm

« someone Italian or Spanish is talking »

David Marjanović said,

July 5, 2024 @ 3:34 pm

I hope not! I've only seen "broad" and "narrow" applied to phonetic transcriptions. For example, increasingly narrow transcriptions of tenth could be:

[tenθ]

[[tʰɛnθ]]

[[[t̺ʰɛ̃n̪̪θ]]]

Phonemic transcriptions, in contrast, are scientific hypotheses about which sounds a language treats as "the same thing" – as the same phoneme – and which are treated as different enough that they can be used to distinguish meaning.

Y said,

July 5, 2024 @ 5:51 pm

From N.A. Walker's Grammar of Southern Pomo:

Philip Taylor said,

July 6, 2024 @ 1:11 am

Garrett — « Randall also missed ,,someone German is talking". » — no, that would be ,,someone German who is still living in the dark ages is talking" — the post-enlightenment version would be „someone German is talking“ …

Jarek Weckwerth said,

July 6, 2024 @ 4:34 am

@David Marjanović: I tend to prefer the term "allophonic" transcription for Mark's second transcription. It's a systematic and essentially phonological transcription ("theoretical" you might even say, as in "not representing a specific speech individual physical event") which makes assumptions about where phonetic events belong. For example, the [ʰ] assumes that the voiceless event that follows the burst of the plosive, which could/should be transcribed as [ɛ̥], belongs with the consonant and is consonantal in nature. Would you use the same for a voiceless /e/ in French?

And what is your first transcription? Since the /n/ will be normally realized as dental in English and the IPA glosses [n] as alveolar, there's a mismatch. It has to be interpreted as a phonemic transcription, in line with your definition that talks about hypotheses. (Unless, of course, it is in fact the transcription of a specific individual speech event where the speaker actually did use an alveolar.)

Y said,

July 6, 2024 @ 12:13 pm

"Broad transcription" does not mean "phonemic", and vice versa. The symbols chosen for broad transcription are often chosen by how familiar they are or how easy they are to type. I don't think anyone transcribes English dogs, cats as /dɔgs kæts/ or as /dɔgz kætz/, even though the final sibilant is the same phoneme.

Philip Taylor said,

July 6, 2024 @ 12:59 pm

Y, I cannot see the connection between your second and third sentences. I think that you would agree that both "s" and "z" are familiar and easy to type, yet I would transcribe "dogs, cats" as / dɒɡz kæts/. I cannot see where familiarity or easy of typing enters into my choice.

Y said,

July 6, 2024 @ 5:00 pm

Philip, right, I am saying people distinguish between s and z in "/ /" transcription because they are familiar letters, even though they represent the same phoneme; which makes calling it a phonemic transcription inaccurate.

Philip Taylor said,

July 7, 2024 @ 3:14 am

Well, with the greatest respect, I would suggest that /s/ and /z/ do not represent the same phoneme. Consider (for example) "eyes" and "ice" (/aɪz/ and /aɪs/) — two different words, differentiated when spoken primarily by the sound of the final element, although I would accept that (/aɪːz/ and /aɪs/) is probably a more accurate transcription and that vowel length may also be significant in this context. However in "sink" and "zink" (/sɪŋk/ and /zɪŋk/), all other factors are constant, and only the initial /s/ or /z/ indicates which word is being used.

Jarek Weckwerth said,

July 7, 2024 @ 7:41 am

@Y "even though they represent the same phoneme" — They represent the same morpheme, yes, but if you want to describe the facts without a recourse to morphology (or morphonology, as some of my friends would say), using phonology only, then the typical solution is to say they are two different phonemes. This is demonstrated by Philip Taylor's ice vs. eyes example, a minimal pair. This is the standard traditional way of deciding what is a phoneme in a language.

Same goes for -ed. Think pact–packed and band–banned vs. tight–tied and bandit–banded. It's more difficult to find the consonant cluster pairs for -s, but think tax–tacks.

But it's true that symbol familiarity is a thing in phonemic transcription, for various reasons.

Jarek Weckwerth said,

July 7, 2024 @ 8:00 am

Posted too soon: Also think joint–joined, and for -s, since–sins.

Daniel Barkalow said,

July 8, 2024 @ 11:37 am

There's a reasonable option for how language is divided into components that allows morphology to produce a segment where the voicing is unspecified and allow phonology to pick it along with applying other transformations on the way to phonetics. This arrangement allows morphology to always produce the same output for a regular plural (once you include an instruction to make sure the segment is distinct somehow, which produces the second vowel in "horses"), and leave it up to phonology to sort out the difference. On the other hand, expressing this theory requires a bunch of characters for things that phonology always transforms and never end up in phonetics.

Jarek Weckwerth said,

July 8, 2024 @ 3:19 pm

@Daniel Barkalow: Yes, this exactly would be morphonology. Which by definition goes beyond phonology.

David Marjanović said,

July 11, 2024 @ 7:47 am

Are you equating aspiration and delayed voice onset? Despite a high degree of correlation, they're two different things that don't sound the same; voice-onset timing is just the most easily measurable proxy of aspiration if you already know that aspiration is the most common source of that in the language in question.

No – and not just because that is much closer to [ç] than to [h].

By default and most commonly, the English /n/ is apical-alveolar. In most of the rest of Europe, the local /n/ is laminal-alveolar. Apical-dental consonants including the local /n/ (or one of them!) are apparently common in India.

I'm not actually sure what happens to /n/ next to /θ/ in English, and to what extent that depends on whether the /θ/ is dental or interdental; there may be too much interference from my native laminal-alveolar /n/. So I just copied the OP.

An important point.

I'll pile on and say it's not the same phoneme because /s/ and /z/ contrast elsewhere in English. It is true they can't contrast in these positions, but it is true for any /s/ and any /z/ that clusters like /gs/ and /kz/ are banned in English; this is not limited to the plural morpheme.

You will absolutely find people transcribing dogs, cats, losses as |dɔg-z kæt-z lɔs-z| at the morphophonemic level to show that 1) there is one plural morpheme with three allomorphs (/z s ɪz/), and that 2) the most common/default/"underlying" form of that morpheme is /z/.

(…Well, | | isn't actually IPA; the least bad IPA has to offer is // //, which means "anything more abstract than a phonemic transcription"…)

Jarek Weckwerth said,

July 11, 2024 @ 9:23 am

@ David Marjanović: Are you equating aspiration and delayed voice onset?

No, not really. I wasn't thinking too much (/enough) about the articulatory-acoustic properties of the thing. I was thinking more in terms of the graphical representation where a small raised symbol to the right of the base symbol in an LTR writing system implies that the small symbol "belongs" to the base symbol on the left.

This doesn't change the fact that this ʰ, or any [h] for that matter, will have the oral configuration, and therefore the resonance, of the neighbouring vowel. (And e̥ is like ç since it's essentially j̊, and that can be found in huge, so…)

clusters like /gs/ and /kz/ are banned in English

They are banned intramorphemically. They're fine as sequences across a morpheme boundary, as in jigsaw, pigsty, drugstore, quickzip. That was my point: to provide a description of where they're allowed, and how the plural / 3rd person morpheme is actually special, you need to refer to the morphology. Phonology on its own (using concepts such as "phoneme") can't do it.