The Miracle of Western Writing

« previous post | next post »

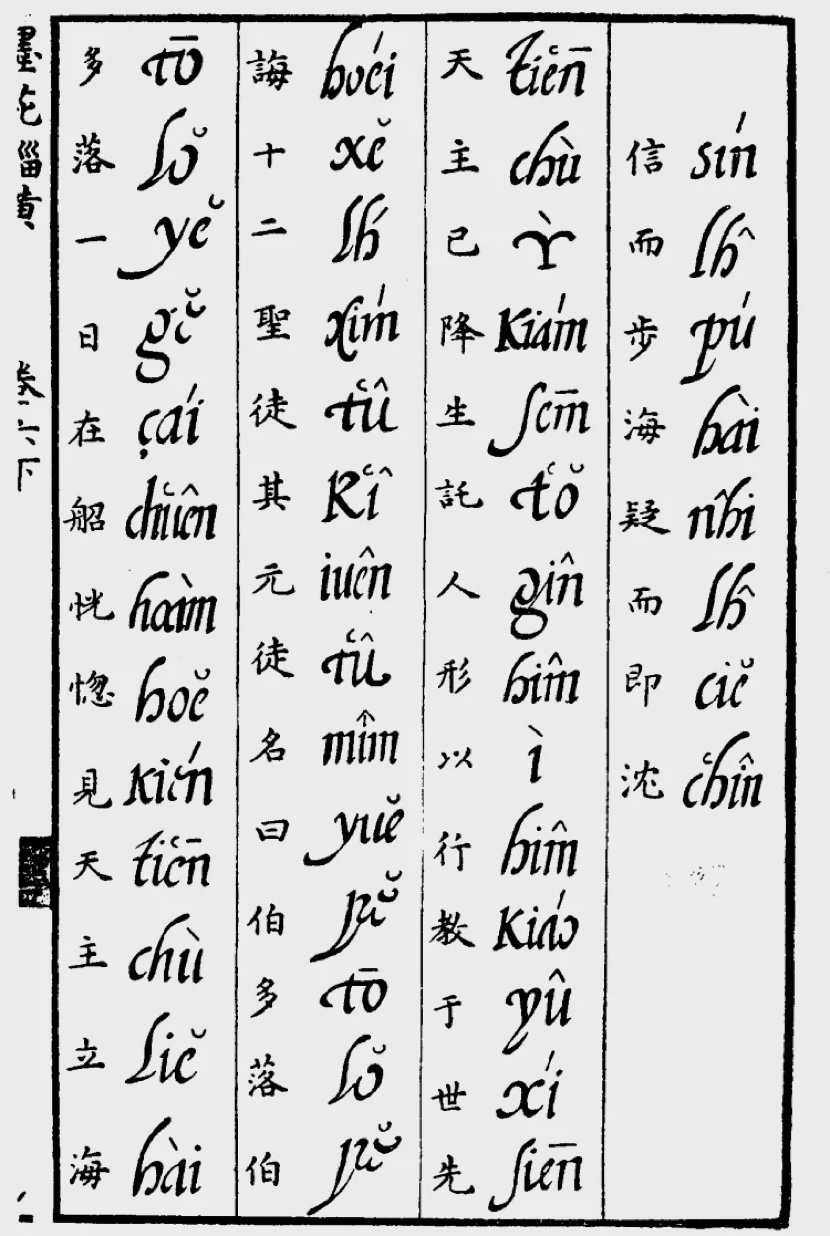

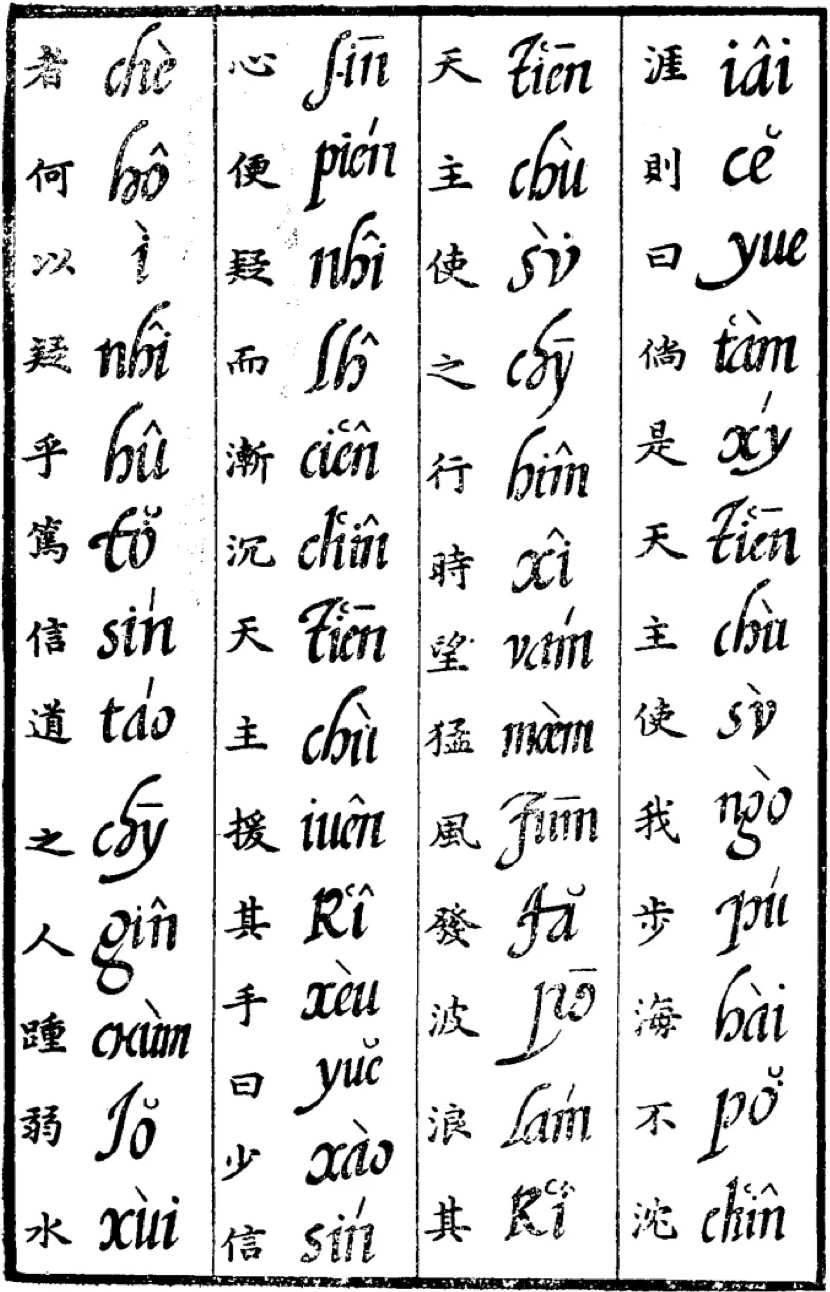

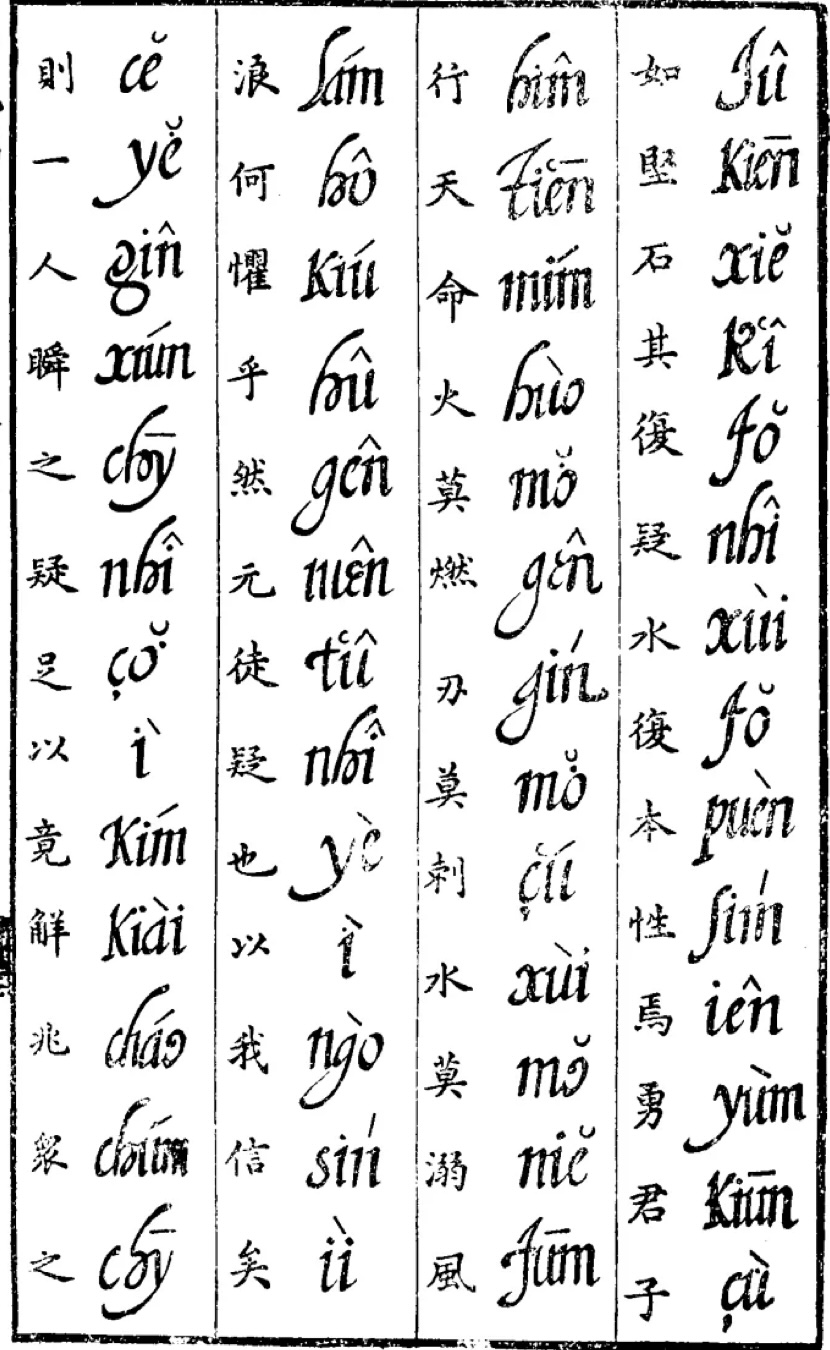

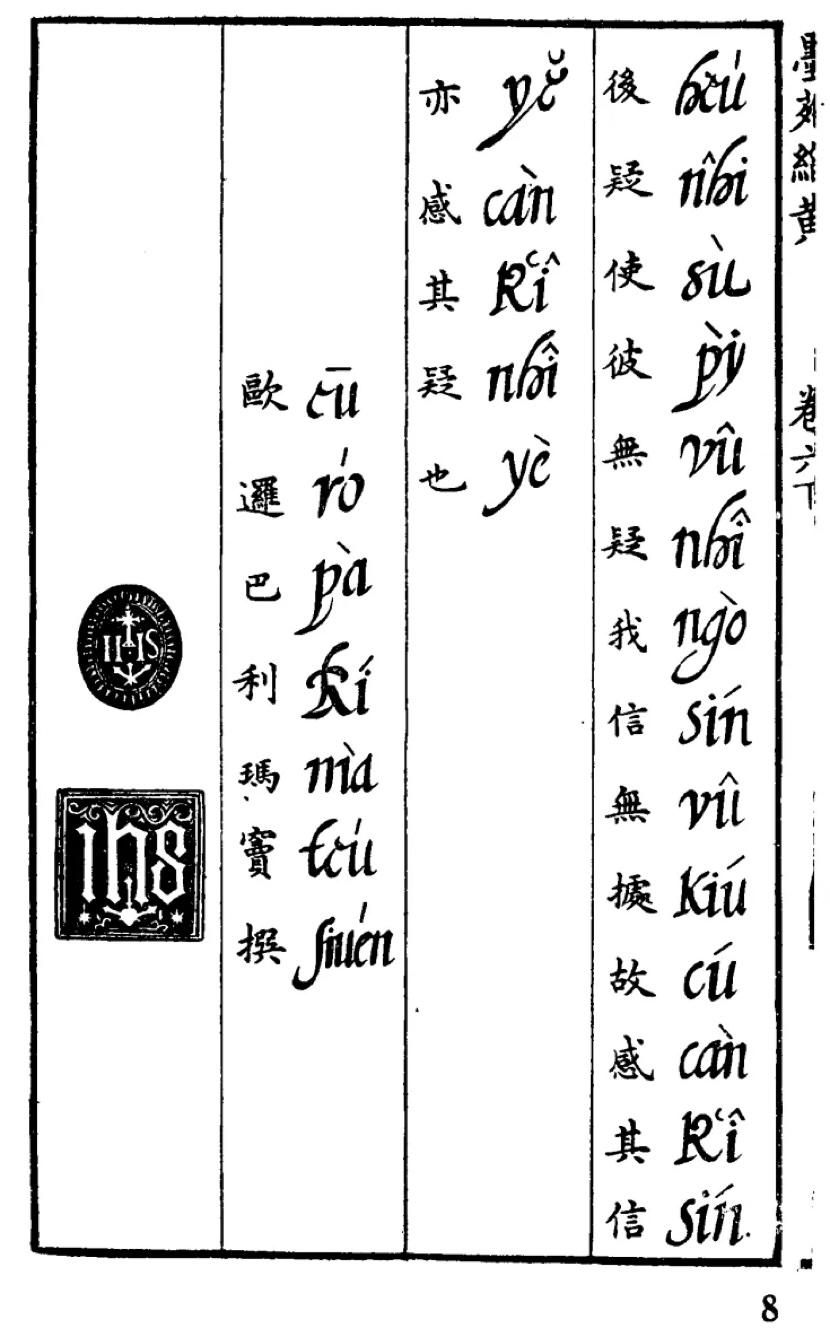

The following essay is from the Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci's (1552-1610) Xī zì qíjì 西字奇蹟 (The Miracle of Western Letters) published in Beijing in 1605. This was the first book to use the Roman alphabet to write a Sinitic language. Twenty years later, another Jesuit in China, Nicolas Trigault (1577-1628), issued his Xī rú ěrmù zī (Aid to the Eyes and Ears of Western Literati) 西儒耳目資 at Hangzhou. Neither book had much immediate impact on the way in which Chinese thought about their writing system, and the romanizations they described were intended more for Westerners than for the Chinese, but their eventual impact on China was enormous, and it is still unfolding.

[N.B.: The following transcriptions of the Chinese text are done into simplified characters, a well-nigh universal practice in the PRC.]

Xìn ér bù hǎi, yí ér jí chén

信而步海,疑而即沉

Believe and walk on the sea, doubt and then sink.

Tiān zhǔ yǐ jiàng shēng, tuō rén xíng yǐ xíng jiào yú shì

天主已降生,托人形以行教于世

The Heavenly Lord was already born and had taken on human form to teach in the world.

Xiān huì shí'èr sheng tú, qí yuán tú míng yuē bó duō luò

先诲十二圣徒,其元徒名曰伯多落。

He first taught the twelve disciples, and his first disciple was called Peter.

Bó duō luò yī rì zài chuán, huǎng hū jiàn Tiān zhǔ lì hǎi yá

伯多落一日在船,恍惚见天主立海涯

One day, Peter was on a boat, when he indistinctly saw the Heavenly Lord standing on the seashore.

zé yuē: "Tǎng shì Tiān zhǔ, shǐ wǒ bù hǎi bù chén

则曰:“倘是天主,使我步海不沉。”

Thereupon he said: “If it is the Heavenly Lord, let me walk on the sea and not sink.”

Tiān zhǔ shǐ zhī xíng shí wàng měng fēng fā bō làng, qí xīn biàn yí ér jiàn chén

天主使之。行时望猛风发波浪,其心便疑而渐沉。

The Heavenly Lord allowed it. As Peter went, he saw that the fierce wind was raising waves; then his heart doubted, and he gradually sank.

Tiān zhǔ yuán qí shǒu yuē: "Shǎo xìn zhě hé yǐ yí hū?

天主援其手曰:“少信者何以疑乎?

The Heavenly Lord lent a helping hand: “A person with little faith, why did you doubt?

Dǔ xìn dào zhī rén zhǒng ruò shuǐ rú jiān shí

笃信道之人踵弱水如坚石,

A person who firmly believes in the way treads on thin water as if on solid rock.

qí fù yí, shuǐ fù běn xìng yān

其复疑,水复本性焉。

Were he to doubt again, the water would resume its natural state.

Yǒng jūn zǐ xíng tiān mìng, huǒ mò rán, rèn mò cì, shuǐ mò nì, fēng làng hé jù hū!

勇君子行天命,火莫燃,刃莫刺,水莫溺,风浪何惧乎!

For a brave gentleman who follows Heaven’s order, fire cannot burn, blades cannot stab, water cannot drown. Why fear wind and waves!

Rán yuán tú yí yě.

然元徒疑也。

Thus, the first disciple doubted.

Yǐ wǒ xìn yǐ, zé yī rén shùn zhī yí, zú yǐ jìng jiě zhào zhòng zhī hòu yí

以我信矣,则一人瞬之疑,足以竟解兆众之后疑。

Considering my faith, then, one person's moment of doubt is enough to completely resolve the subsequent doubts of many.

Shǐ bǐ wú yí, wǒ xìn wú jù. Gù gǎn qí xìn yì gǎn qí yí yě”

使彼无疑,我信无据。故感其信亦感其疑也。”

If I were to cause him to be without doubt, my faith would not have proof; therefore, I arouse his faith and also his doubt.”

Ōu luó bā lì mǎ dòu zhuàn

欧逻巴利玛窦撰

Written by European Matteo Ricci

For woodblock printing, the shapes of the letters are exceedingly graceful. They somehow seem to combine the flowing quality of cursive with the clarity of printing. It is a pleasure simply to behold the artistry of the writing. Reading the text affords additional satisfaction due to its simple and straightforward elegance of expression.

Selected readings

- "The invention of an alphabet for the transcription of Chinese characters half a millennium ago" (11/21/22) — based on Takata Tokio's detailed codicological study of Matteo Ricci's Jesuit colleague, Nicolas Trigault (1577–1628), whose Xīrú ěrmù zī 西儒耳目資 (An Aid to the Eyes and Ears of Western Literati)

- "Misprint on Chinese money" (7/1/13) — in the comments

- "Matteo Ricci's tombstone" (11/24/21)

- "Candida Xu: a highly literate Chinese woman of the 17th century" (7/7/20)

- Victor H. Mair, "Sound and Meaning in the History of Characters: Views of China's Earliest Script Reformers", pinyin.info. From Difficult Characters: Interdisciplinary Studies of Chinese and Japanese Writing, edited by Mary S. Erbaugh, copyright © 2002 by the National East Asian Languages Resource Center of the Ohio State University. Used by permission of the National East Asian Languages Resource Center.

[Thanks to Zhaofei Chen, who did the transcriptions and the translations]

Philip Taylor said,

December 31, 2023 @ 6:26 pm

I agree that "the shapes of the letters are exceedingly graceful. They somehow seem to combine the flowing quality of cursive with the clarity of printing. It is a pleasure simply to behold the artistry of the writing" but is it really possible that Xī rú ěrmù zī (西儒耳目資) can mean "Aid to the Eyes and Ears of Western Literati" ? So much meaning packed into just five Hanzi ?

Victor Mair said,

December 31, 2023 @ 8:12 pm

The 5 hanzi mean what the 5 capitalized English words indicate: Western Literati Ears Eyes Aid. That's basically how we read Classical Chinese / Literary Sinitic that is easy and straightforward.

Philip Taylor said,

January 1, 2024 @ 5:24 am

Thank you Victor — I asked both Google Translate and ChatGPT before commenting, but the former was almost completely flummoxed whilst the at least managed "Western Confucian intelligence".

katarina said,

January 1, 2024 @ 11:28 am

They are flummoxed because the five characters are in Classical Chinese, not in present-day Chinese, i.e., they are in Classical Chinese grammar. One of the beauties of Classical Chinese is its extreme brevity.

katarina said,

January 1, 2024 @ 11:40 am

Thank you, Professor Mair, for this wonderful information about Matteo Ricci and Nicolas Trigault

For a non-linguist, I am very glad this is Language Log and not

Linguistics Log, because we can learn, through the LL postings , so much about language as well as about culture and civilization.

Happy New Year !

Philip Anderson said,

January 3, 2024 @ 2:58 pm

With Professor Mair’s explanation, I can see how those five characters express the meaning given. How would the same sense be expressed in modern Mandarin? Less tersely I assume.

katarina said,

January 4, 2024 @ 7:19 pm

There are various ways to translate the five characters into Modern Chinese. Two are given below.

1). 西方文人對耳目的協助 (10 characters)

xifang wenren dui ermu de xiezhu

is translated by Google Translate as

"Western literati assist the eyes and ears."

2) Another translation into Modern Chinese is:

西方學者對視聽的協助 (10 characters)

xifang xuezhe dui shiting de xiezhu

which Google Translate renders as

“Audio-visual assistance from Western scholars。”

katarina said,

January 4, 2024 @ 7:49 pm

Oops, I mis-translated above.

A correct translation of the five characters would be

給西方文人視聽的協助 (10 characters)

gei xifang wenden shiting de xiezhu

"Audio-visual assistance to Western literati"

There are other ways of translating the five characters of course.

katarina said,

January 4, 2024 @ 7:53 pm

Correction:

wenden above should be wenren ("literati')

Philip Anderson said,

January 5, 2024 @ 8:37 am

Thank you katarina.

As well as both using ten characters, your two translations are different according to whether Western literati is the subject or the indirect object, but I assume that both are valid, and the Classical Chinese could actually mean either, with the context used to resolve the intended meaning?

Back when Old Chinese, or Middle Chinese, was a spoken language, would the same ambiguity have been allowed as in the literary language? Do we know how spoken and written forms differed?

Victor Mair said,

January 5, 2024 @ 9:50 am

@katarina:

Thanks for trying your hand at the Mandarin translations. I have organized an "experiment" among my students from China, and will post the results later.

@Philip Anderson:

The questions you ask in your last comment are huge, and we are only chipping away at them bit by bit. Some of the research is mentioned on Language Log from time to time, so keep your eyes peeled. For the time being, I will only say this: there was already a sharp discrepancy between spoken vernacular and written literary forms of Sinitic well over two millennia ago. There were enormous topolectal differences as well.

liuyao said,

January 5, 2024 @ 10:27 am

On the topic of language and script, Prof Mair would love this story: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0dtTBDEXVYY

katarina said,

January 5, 2024 @ 1:57 pm

@ Philip Anderson said:

"your two translations are different according to whether Western literati is the subject or the indirect object, but I assume that both are valid, and the Classical Chinese could actually mean either, with the context used to resolve the intended meaning?"

Exactly, Philip. In the first translation, I had forgotten context, which was foreigners in China in the late 16th century and early 17th century. The eye-ear aid with alphabetical spelling would not have been intended for the Chinese populace because they didn't know the alphabet at that time. The aid was for foreigners.

The five characters 西儒耳目資

"Western literati ear eye aid"

can be parsed in two ways:

1). 西儒 耳目資

" Western literati ear eye aid"

and

2). 西儒耳目 資

"Western literati ear eye aid"

The first meant ear-eye aid for everyone.

The second meant aid for Western literati's ears-eyes.

Context (16th-17th century) mean aid for Westerners.

By the time I made my translation I had forgotten Prof. Mair's translation:

"Aid to the Eyes and Ears of Western Literati".

Classical Chinese sentences can indeed be ambiguous because of the paucity of relational indicators.

katarina said,

January 5, 2024 @ 2:10 pm

My comments above do not reflect my original spacing. .

Here it is again. I maintain that there are the two ways of parsing the five characters;

1. (西儒). (耳目資)

"(Western literati) ( ear eye aid)"

meaning "Ear eye aid from Western literati"

2. (西儒耳目) (資)

"(Western literati ear eye) ( aid)"

meaning " Aid for Western literati's ears and eyes"

Victor Mair said,

January 5, 2024 @ 9:23 pm

Yes, indeed, liuyao. It is something I wrote about several times in the past, and will write about again now.

감사해요