Man bites dog

« previous post | next post »

Email from Michael Ramscar:

inspired by your last couple of langlog posts, i decided to pull together some things that look at frequency of mention versus social changes that can be quantified objectively. i made a few slides, that i've attached.

The slides are here, and I've also turned a slightly edited version into a guest post:

How well does "frequency of mention" correlate with quantifiable aspects of culture?

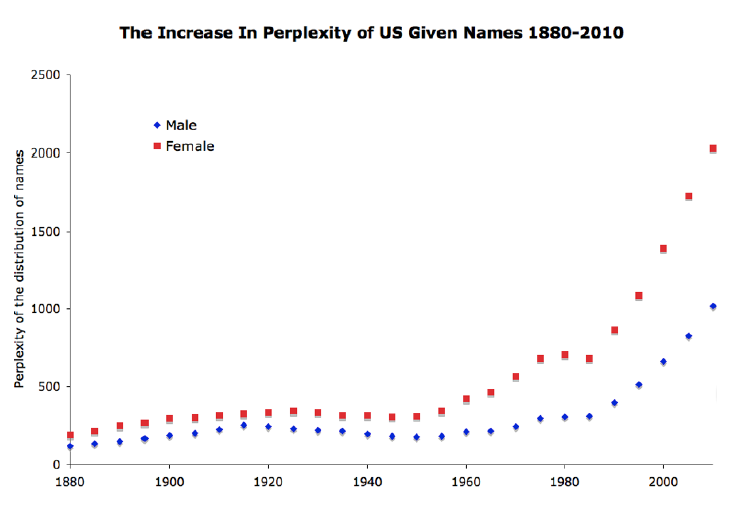

1. Are names getting easier to remember?

Nope. Until 1750, English names were as easy to remember as Korean names. Since 1960, there's been a sharp increase in perplexity:

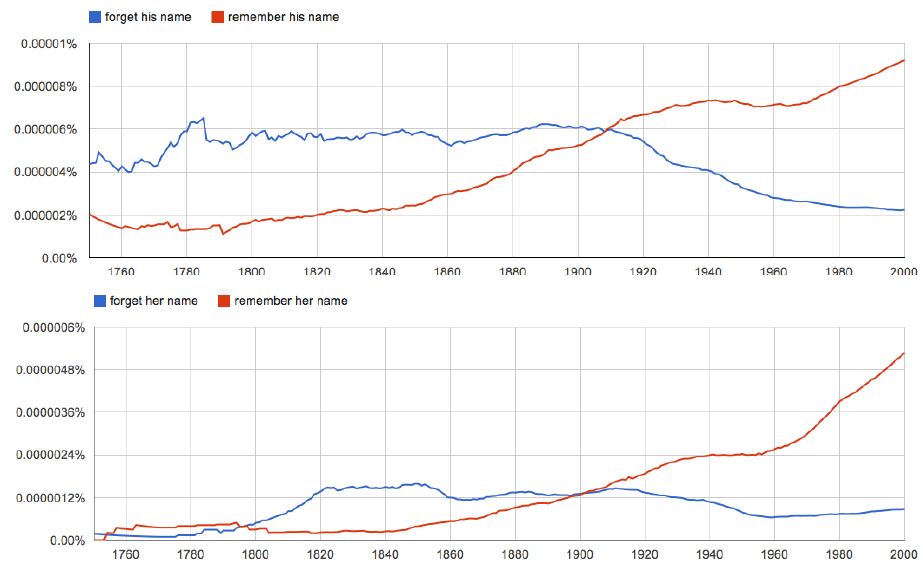

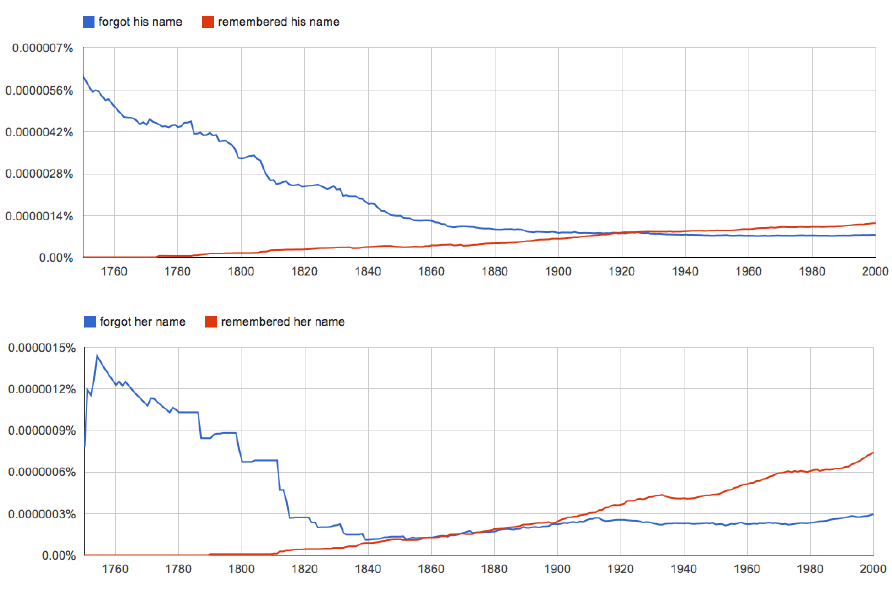

So does that mean that people now talk about forgetting names more often?

Nope:

And:

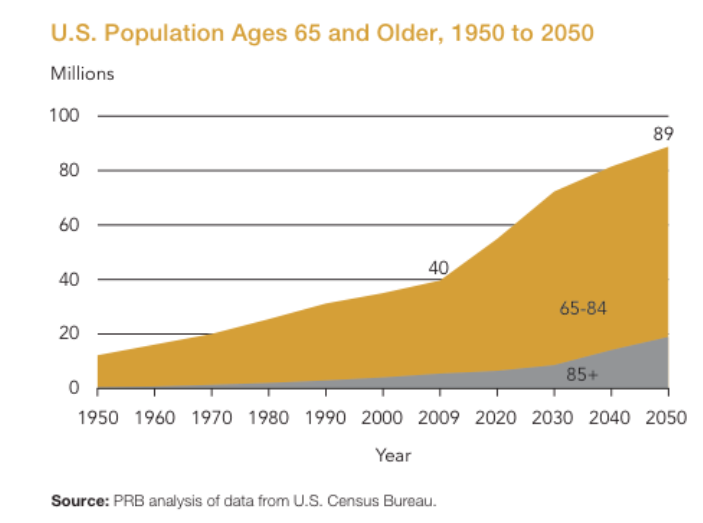

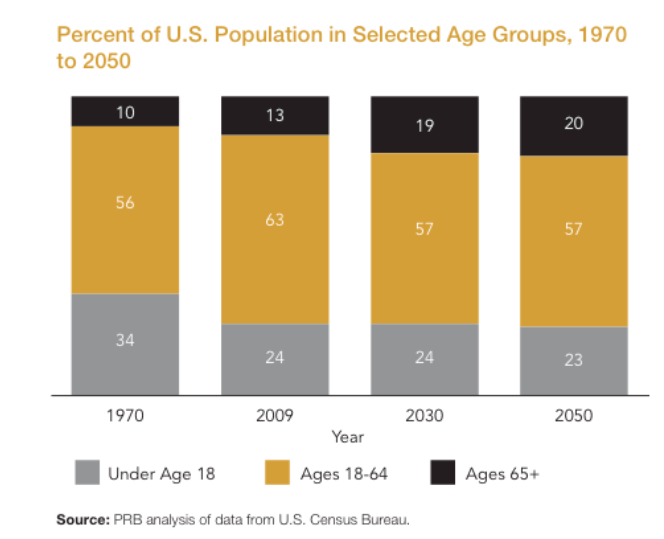

2. Are populations getting older or younger?

Older:

Definitely older:

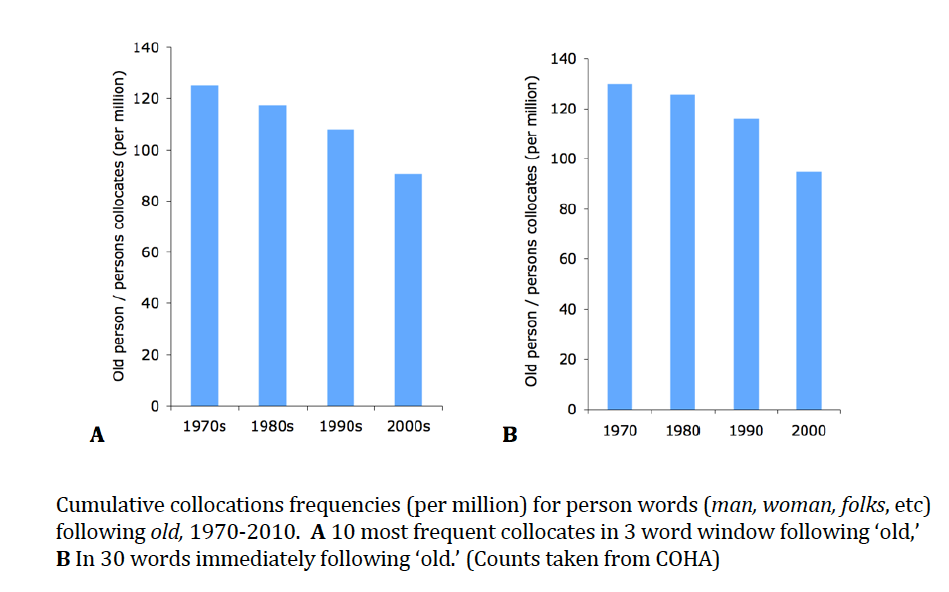

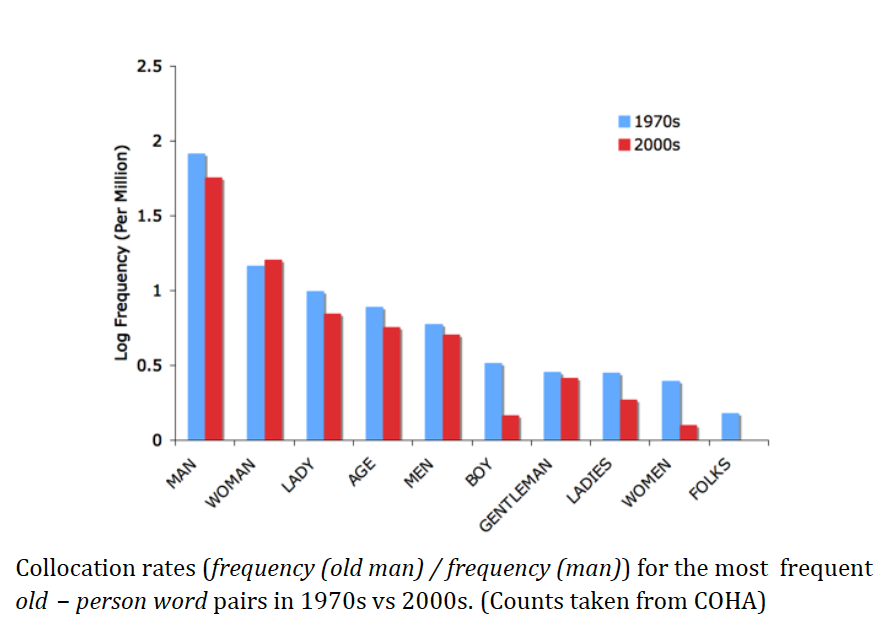

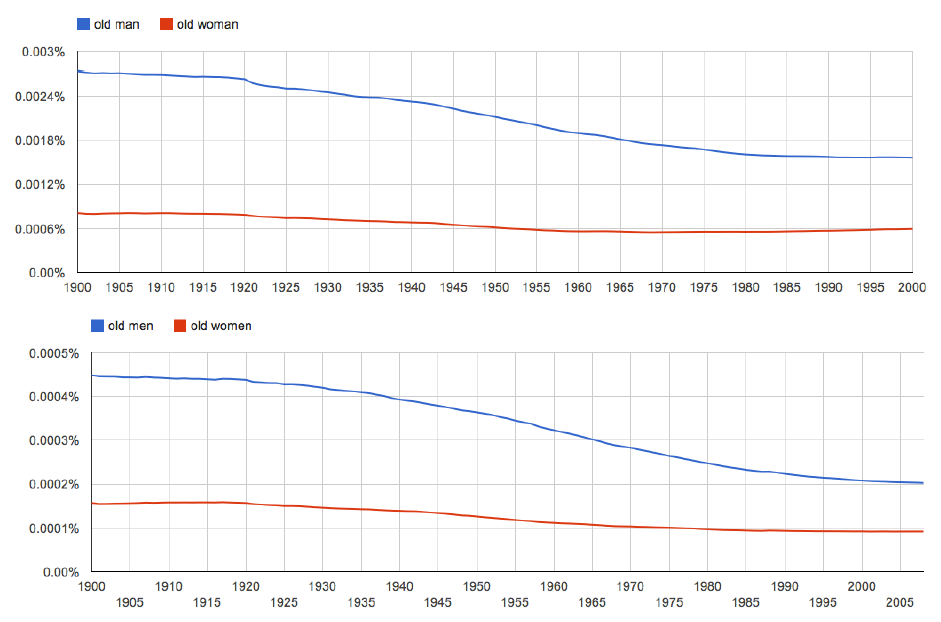

So does that mean that people now talk about old people more often?

Nope:

Really, no:

Absolutely not:

"Dog bites man" or "Man bites dog"?

What are the facts?

Names are getting harder to remember, so presumably we forget names more often.

What are the frequencies?

We talk about forgetting names less often.

What are the facts?

The population is getting older.

What are the frequencies?

We have become less likely to talk about old people.

Why do people talk? And what does "frequency of mention" tell you about what they care about?

[Above is a guest post by Michael Ramscar]

J.W. Brewer said,

August 20, 2013 @ 1:59 pm

The increasing demographic and political salience of old people has inexorably led to the development of euphemisms for referring to them (e.g. "senior citizen") and an accompanying taboo against just calling them "old people." Or at least that's the theory I just made up, and the data fits it perfectly!

There's an equally obvious just-so story for the other one: increasing dispersion in naming patterns might make it easier to match names to faces when there is only one person in your social circle with a particular name, whereas in the old days when a high school class of a few hundred would include ten Johns, eight Bobs, seven Bills, etc. it was easier to get names-v.-faces muddled in certain ways – or so I hypothesize.

[(myl) Michael's theory, I think, is a general form of our earlier observation that the word "parking" is unusually frequent in Boston real-estate listings precisely because parking spaces are so rare and precious in downtown Boston real-estate market…]

J.W. Brewer said,

August 20, 2013 @ 2:10 pm

Come to think of it, "perplexity" seemed like such a stupid thing to call the y-axis on that first graph, I belatedly wondered if it was a technical term I didn't know (having not all that much to do with the common non-technical meaning of "perplexity"), and I was right. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perplexity. But now I'm wondering if Dr. Ramscar is engaged in some sort of deadpan joke I shouldn't be falling for.

[(myl) I think that Michael is always engaged in some sort of deadpan joke that you shouldn't be falling for, but in this case he's also entirely serious, and the use of "perplexity" (to mean "2H", where H is entropy) is routine in information-theoretic discussions.]

Christopher Hodge said,

August 20, 2013 @ 2:16 pm

Purely as a mathematician, I'd say if the population were getting older, we would indeed expect to hear less talk of "old people", as any given speaker would (since older himself, statistically) have fewer people around which he himself would regard as old.

Jon Weinberg said,

August 20, 2013 @ 2:29 pm

I love the column, but I'm confused about name perplexity, a concept I hadn't been familiar with. Google leads me to a paper by Popescu, for whom (if I understand him correctly) the perplexity of a name is directly related to its frequency — Smith as a surname is more perplexing than Cadwalader-Smith, because it's less clear what individual I'm referring to when I say the name. But if that's the concept, (a) surely the perplexity of U.S. given names has been falling, not rising, since we have greater variation in given names now than in the past; and (b) it's not obvious to me whether it's rare names or common ones that are easier to remember in any event.

[(myl) "Name" is a familiar concept, and "perplexity" is a familiar concept (at least in applications of information theory), but "name perplexity" is a fresh combination, I believe. For more background, you could read Michael Ramscar et al., "The ‘universal’ structure of name grammars and the impact of social engineering on the evolution of natural information systems", Cogsci 2013.]

hector said,

August 20, 2013 @ 2:38 pm

This is anecdotal, I know, but recently I had an appointment with a neurologist in regard to an odd symptom I was having. He told me he didn't know its cause, but it would likely go away in time, so I shouldn't worry about it. I said that the trouble with getting old was, when something odd occurred with your body, you never knew whether it was something serious, or just the one of the generalized creaks and crumbles of age. He said, "You're not old! You're only 63!"

I said, "Well, the most I can expect to live to is 90, unless I'm really lucky. So youth is 0-30, middle age is 30-60, and old age is 60-90. Right?"

His reply: "Let's not go there." I should add he appeared roughly the same age as me.

So my theory would be that people aren't talking about old age because they don't want to go there, even if they already are there.

Brandon said,

August 20, 2013 @ 2:55 pm

Maybe it's just choice of phrase that's changed. Did you include instances of "[can't,couldn't,don't] remember [his,her] name" in the hits for forgetting, or even filter them out of the hits for remembering? Personally, I say "can't remember" far more often than I say "forget."

J.W. Brewer said,

August 20, 2013 @ 2:59 pm

I am skeptical that Popescu is using "perplexity" in the same information-theoretic sense. I think (based on a brief scan of a wikipedia article, so …) that having more rather than fewer different words/n-grams/character-strings/whatever in your corpus necessarily increases "perplexity" even though having more rather than fewer distinctive names for things may in the real world quite usefully decrease ambiguity. So, e.g., a computer doing NLP faced with a discourse beginning "Dude, I met this totally hot chick at this party last night. Her [first] name was ____" will be confronted with greater "perplexity" in terms of guessing at the next word now than (in Anglophone culture) would have been the case in prior centuries.

I wonder if surname perplexity (in that sense) is increasing or decreasing in the U.S., at least adjusted for population size The country is getting more "diverse," as they say, but some of the growing ethnicities (e.g. Hispanic/Chinese/Korean/Vietnamese) have fairly highly-concentrated surname patterns, and they might be taking relative market share away from ethnic groups with less-concentrated surname patterns.

Daniel said,

August 20, 2013 @ 3:09 pm

I have to agree that there's less talk of old people, for example, because more people are old. This may be similar to patterns in Italian last names: the most common name in Italy is Rossi/Russo (red[-haired]), not because red hair is common in Italy, but precisely because it's rare.

D.O. said,

August 20, 2013 @ 4:17 pm

Based on previous comments I am about to conclude that perplexing is an autonym.

J.W. Brewer said,

August 20, 2013 @ 5:20 pm

I am grateful for myl's link to the Ramscar et al. "universal structure" paper, but think its more speculative suggestions could use some more tirekicking. For example, the rise of highly-unusual given names in (some) segments of the black community (where there's no good national dataset, so everyone is assuming that local datasets from e.g. California and New York City scale up adequately . . .) is usually said to be a quite recent phenomenon (i.e. not really getting underway until kids born in the '70's, whereas the hypothesized driver for increased first-name variation (a more limited stock of surnames) has been out there for a much longer period. And the stock of common black surnames is primarily limited by a lack of "ethnic" diversity – i.e. it largely corresponds to the stock of common British-origin surnames found in the white population south of the Mason-Dixon line prior to 1860 (although the racial mix of the bearers of particular surnames shared by both of those groups can vary considerably from surname to surname). One could in principle separate out WASP's from the white population at large by surname and see if they have more or less variability in first names than whites-in-general (and because white surnames vary by ethnicity and different parts of the country have different ethnic mixes, you can probably find states with materially higher and lower degrees of surname concentration and see if there's any corresponding variation in first-name concentration). And again, as noted above, America's burgeoning Hispanic population has a fairly small and highly-concentrated stock of surnames (even compared to the WASP-surname element of the non-Hispanic white population). What are they doing with first names? Does whatever they're doing create a testable hypothesis for Ramscar et al. as to how easily remembered or forgotten the names of individual Hispanic Americans ought to be, which could then be tested against their hypotheses as to the social/economic advantages of an easily-remembered name?

I do appreciate their concession that "Given that the period since 1950 saw an increase in economic and social equality between males and females in the US (Fullerton, 1999), the close relationship (Figure 6A) between the growth in the perplexity difference between male and female names and the increasing percentage of females in the workforce is surprising, as is the fact that increases in the number of women working outside the home have coincided with an exponential increase in the degree to which female names are harder to process than male names." Of course, "surprising" may just be a polite way of saying "we're still not giving up on our theory despite its apparent failure to account for the data."

Ellen K. said,

August 20, 2013 @ 5:44 pm

Brandon makes a good point. The "remember his/her name" results would include things like "can't/don't/couldn't remember his/her name". Same for "forget", thought likely not in the same proportion.

Maryellen MacDonald said,

August 20, 2013 @ 6:18 pm

These very interesting data assume the equivalence of [frequency of collocation] and [what people talk about]. This linkage falters if speakers use other expressions than those reported. For example (1) the rate at which people talk about forgetting a name is estimated with "forget…name" but people also use "can't remember his/her name" to report the same idea. As far as I can tell from the graph, utterances like "can't remember" incorrectly contribute to the "remember" data and not to the rate of people talking about forgetting names. (2) The rates of "old NP" do not exhaust the range of common expressions to refer to old people. There's also senior citizen/seniors, AARP member, older adults/Americans/etc., retired people/voters, people on social security, pensioner, and many other choices. The data clearly show that there's not increasing use of "old NP" or "forget [name]" but the link to rates of what people talk about doesn't yet seem established.

dainichi said,

August 20, 2013 @ 6:38 pm

@Jon Weinberg

"because it's less clear what individual I'm referring to when I say the name"

@J.W. Brewer

"increasing dispersion in naming patterns might make it easier to match names to faces"

Just so there's no confusion, we're talking about the scenario where we have a person/face and are trying to retrieve the name from memory, not vice versa. Obviously this will be easier the fewer people there are, all other things equal.

But of course, you might argue that if there is only very little variation in names, people might find the whole concept of naming less useful and make less of an effort to remember names.

I'm not so sure entropy/perplexity is a better measure than e.g. something based on Kolmogorov complexity, i.e. something that actually takes into consideration the complexity of names, not just the variation. If names were keeping the same distribution, but getting longer/increasingly complex, they could still be harder to remember.

@Christopher Hodge

If you select 2 people randomly, one will have 50% chance of being older than the other regardless of the age distribution of the population. Sure, the average speaker will be older, but so will the average people around the speaker. If you really want to be logical about it, I think you need a more exact model about who regards who as old.

Matt said,

August 20, 2013 @ 7:25 pm

Why do people talk? And what does "frequency of mention" tell you about what they care about?

So what you're saying is, the Inuit actually have no words for snow at all! Someone get the BBC on the line!

Alan Palmer said,

August 21, 2013 @ 4:11 am

As an "old" person myself (65) I don't really consider myself or my peers old – I still feel 20 inside, although the outside is showing signs of wear. There are more people writing now and thus contributing to the corpora; if they are like me the won't refer to "old people" so frequently.

Rodger C said,

August 21, 2013 @ 8:19 am

@Alan Palmer: I'm 65 myself and prefer "people who inexplicably seem to remember more than most of the people around me." ;)

America's burgeoning Hispanic population has a fairly small and highly-concentrated stock of surnames (even compared to the WASP-surname element of the non-Hispanic white population). What are they doing with first names?

Cf. all the Welsh people who, for the past 200 years or so, have borne names like Blwchfardd Evans.

Mark F. said,

August 21, 2013 @ 1:13 pm

Going back to the paper itself, the ideas are interesting. A couple of things it made me think of–

When I started college in the 80's, my dad was surprised that everybody introduced themselves by first names only. I was actually a bit surprised at that myself, even though I was in the relevant age cohort. Two generations earlier I have the impression people tended to lead with their last names, and in between I have the sense that giving both names was more common. This is probably part of a large, long-term trend towards informality, but the change in effectiveness-as-a-distinguisher of first names may have something to do with it.

To the extent that this is a problem, I have a proposed solution. When people marry, the one with the more common surname should be the one to change their name. This will increase the perplexity of surnames, opening up room for reducing that of given names.

J.W. Brewer said,

August 21, 2013 @ 1:22 pm

Well, whether with the Welsh-surnamed or the Hispanically-surnamed, it's an empirical question that can (given an adequate dataset) be empirically answered. One subtlety, by the way, that the historical comparisons don't capture is the role of nicknames. In an Anglophone community where 10%+ of all girls are nominally named "Elizabeth," that's not the whole story, because in any given social context you have to know who's Liz v. Lizzie v. Beth v. Betsy v. Betty etc etc. (One Elizabeth I went to elementary school with was in practice named "Tish.") And similarly, I don't know about Korean culture, but in Chinese culture my understanding is that people are frequently addressed and/or referred to both in family and in social contexts by all sorts of nicknames that may or may not transparently derive from their "official" names (now sometimes including an additional Western-sounding first name acquired for purposes of e.g. high school English class but sometimes used in broader social contexts), so a metric of naming-recall efficiency based on mathematical analysis only of a dataset of official names will not provide the whole picture. In most instances, we probably don't have good enough datasets to quantify the precise impact of the nickname phenomenon on the issues being discussed (because governments tend not to collect and tabulate nicknames with any consistency — although in Singapore and Hong Kong individuals may be more likely to officially have both a Western-style given name and a Chinese-style given name reflected in government records), but the lack of data doesn't mean the issue can just be assumed away absent a plausible demonstration that it is safe to think its impact on the bottom line results of the analysis would be immaterial.

Jonathan D said,

August 21, 2013 @ 9:32 pm

Like Dainichi, I take references to not remembering names as being about "the scenario where we have a person/face and are trying to retrieve the name from memory, not vice versa". The Ramscar et al. paper seems to be talking about both situations, although as someone with no knowledge about this field, it's not at all clear to to me how the difficulties and longer latency times referred to should relate to concious lack of memory.

Mark said,

August 21, 2013 @ 10:29 pm

I find these data deeply puzzling. They seem to be additional examples of how to make errors like Greenfield's. Were they intended as such? Am I missing the joke?

Ken Brown said,

August 27, 2013 @ 5:16 pm

If "Rossi" is a common Italian surname because red hair is rare, why is "Brown" such a common British surname?