What happened to all the, like, prescriptivists?

« previous post | next post »

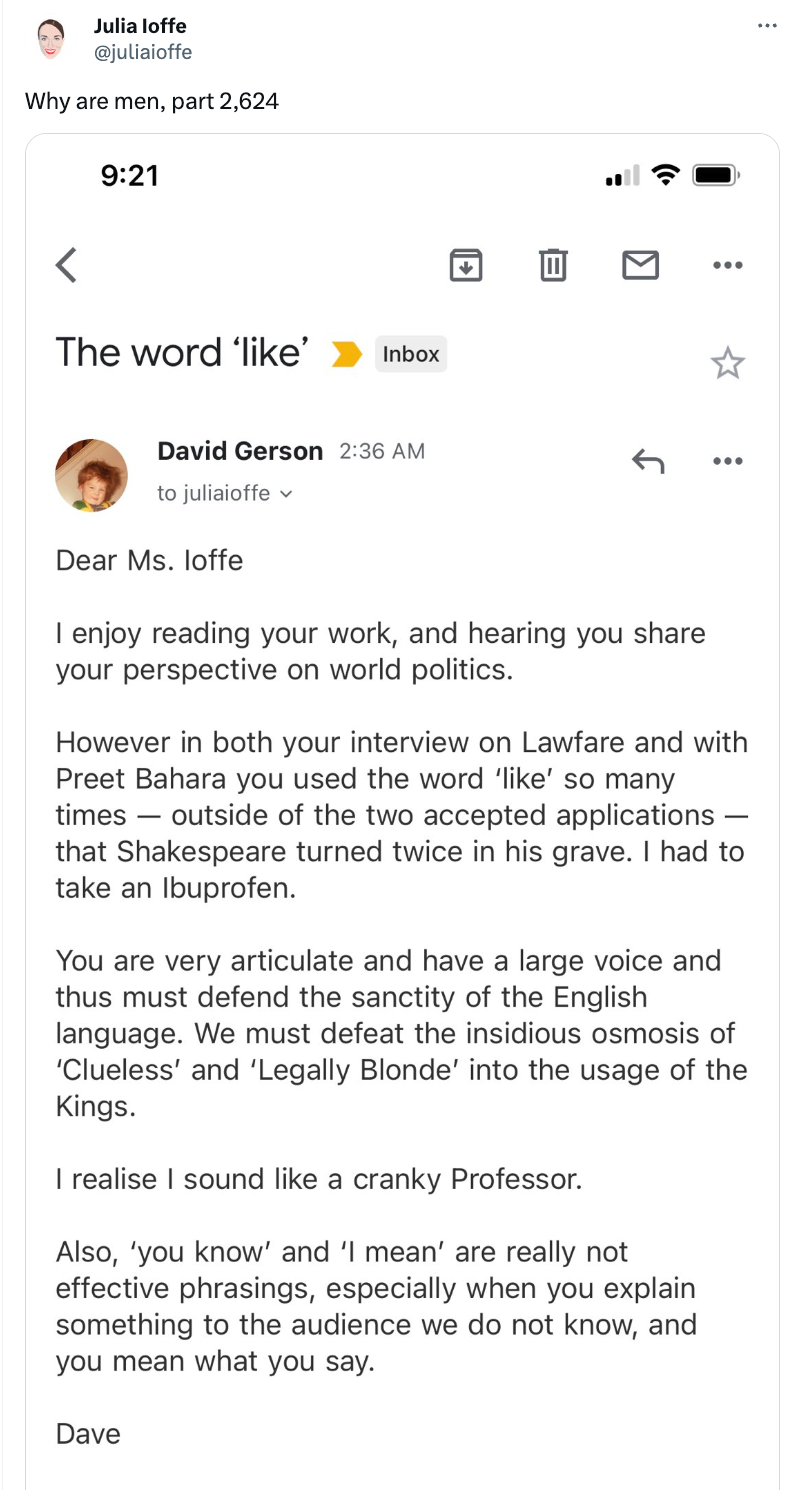

A tweet by Julia Ioffe from 10/4/2022 (image below because twitter embedding seems to be broken…):

These are the cited interviews:

"Putin's Nukes (with Julia Ioffe)", Stay Tuned with Preet 9/29/2022

"What's Going on in Russia, with Vindman and Ioffe", The Lawfare Podcast 10/3/2022

And a quick scan suggests that "David Gerson" is over-sensitive to the point of hallucination. I don't have time this morning to check in greater depth, but Julia Ioffe's first (2-minute-long) answer in the Lawfare podcast contains not a single instance of like, you know, or I mean:

Not that few fillers, hedges, or discourse-markers would have been anything to complain about… See below for some past LLOG discussion of (complaints about) such things.

But what struck me most about David Gerson's complaint was not its weak empirical and linguistic basis, but rather its very existence. Where have all the prescriptivist peevers gone?

Once mass-media sources were rife with columns and op-eds complaining about kids today and their ignorant, illogical, annoying language. And the growth of social media has given a megaphone for the expression of every sort of prejudice — except, I think, this one.

Are there fewer linguistic peevers out there? Have the counter-peeving arguments gained ground? Or have linguistic peeves been displaced or overwhelmed by other arguments about other issues?

Or am I just wrong about this?

"It's like so unfair", 11/22/2003

"Like is, like, not really like if you will", 11/22/2003

"Exclusive: God uses 'like' as a hedge", 1/3/2004

"Divine ambiguity", 1/4/2004

"Grammar critics are, like, annoyed really weird", 2/13/2004

"Seems like, go, all", 11/15/2004

"I'm like, all into this stuff", 11/15/2004

"I'm starting to get like 'This is really interesting'", 11/16/2004

"This is, like, such total crap?", 5/15/2005

"Language Log like list", 5/26/2005

"Like totally presidential", 8/17/2007

"'Like' youth and sex", 6/28/2011

"If you will…", 7/29/2011

"Americans: 90% on the right, if you will", 7/30/2011

"A floating kind of thing", 1/12/2012

"'I feel like'", 8/24/2013

"Like thanks", 11/26/2015

Update — since Philip Taylor was triggered by the single example of discourse-marker "like" in the podcast's into, I've added the audio to Ioffe's second (2:29) answer below, which is also devoid of other examples:

So there's one example of discourse-marker "like" in the first 5 minutes of her side of the podcast, which (given the expected speaking rate of about 200 words/minute) amounts to about a thousand words. Hypersensitivity much?

Philip Taylor said,

October 6, 2022 @ 6:21 am

In the link provided to ""What's Going on in Russia, with Vindman and Ioffe", The Lawfare Podcast 10/3/2022", I find the first unnecessary "like" at approximately 22 seconds in — ("like, there is really, not any doubt that …").

As regards "Where have all the prescriptivist peevers gone?", at least one is alive and well and comments regularly on Language Log.

[(myl) [Apologies for the earlier version of this comment — I was tired and grumpy.]

Philip ignored the 2-minute answer that I cited in the post, which (as I wrote) is devoid of any relevant expressions, and instead noted the one (in my opinion entirely unproblematic) instance of "like" in a 30-second quote used in the podcast's intro. For other examples of that type of "like" from various professors, U.S. Presidents, and God, see the links at the end of the post.

I should add that the relevant uses of "like" are sanctioned by the OED, with citations going back to 1788:

like, adj., adv., conj., and prep.

6.a. Used conversationally to qualify a preceding (or in later use also following) statement, suggesting that the statement is approximate, or signifying a degree of uncertainty on the part of the speaker as to whether an expression is pertinent or acceptable: ‘as it were’, ‘so to speak’, ‘in a manner of speaking’. Also used simply as a filler, or as an intensifier used to focus attention on the statement retrospectively.

]

LW said,

October 6, 2022 @ 6:22 am

two possible hypotheses:

1. the people who used to write most of those op-eds have now retired, and younger people don't care (as much).

2. the people who complain about linguistic peeves also tend to be people who complain about social media. complaining about social media has become a very popular point of view these days, and so many of them had to delete their accounts to avoid looking like hypocrites that they aren't around to write about their peeves anymore.

or a more positive alternative explanation: i remember when LL used to have (it seemed like) weekly posts on terrible science reporting by the BBC News website. those seem to have dried up as well – could it be that media outlets have started to reassess whether publishing junk science (including language peeving) is something they should be doing?

Michael M said,

October 6, 2022 @ 6:44 am

I think there are two somewhat-related explanations, both largely having to do with leftish politics, and then a third highly speculative one.

1) It is difficult to separate prescriptivism from stigmatisation of non-standard dialects. You can complain about the kids these saying 'like' too much, but a lot of complaints sound like you're devaluing about AAVE, or even just the English of L2 speakers. Tricky ground in some circles, especially elite publications.

2) The kind of people who love policing language now police political language. It was always more about being right and correcting people rather than specific principles, so now these people go around correcting 'seniors' to 'older adults' and what have you. This is now a marker of prestige dialect much more than formally correct speech is, especially online.

3) Speculative, but most of the things prescriptivists used to complain about are part of my speech, and I'm nearly 40. My generation should be complaining about Zoomer speech, but I don't know what the stereotypes around it are. Maybe due to social media innovations have less of a generation gap, or conversely the TikTok world is so separate from my world that I don't hear their speech often enough. But I genuinely don't know if I wanted to complain about the 'kids these days,' what I'd complain about!

Philip Taylor said,

October 6, 2022 @ 6:52 am

I did indeed "ignore the 2-minute answer that [Mark] cited in the post", preferring to go to the audio recording itself to hear what she had actually said. Whilst I do not believe for one second that Mark selected the two-minute extract because it demonstrated the point that he was seeking to make, others, less honourable, might well do so, and I therefore always prefer to go to the original source rather than to an extract cited.

[(myl) I didn't just "cite" the answer, I linked to the audio. It's the full audio of Ioffe's first reponse in the podcast.]

As to whether her first "like" is unnecessary or "[just an] other example of that type of 'like' from various professors, U.S. Presidents, and God", clearly that is subjective, but for me, a 75-year-old native speaker of British English, it is totally unnecessary and adds nothing whatsoever to the discourse.

[(myl) With all due respect, an interview with any one of us is going to have some bits that others might consider "totally unnecessary" — and we ourselves might well agree.]

Cervantes said,

October 6, 2022 @ 7:14 am

It is certainly part of the human condition to insert the occasional filler or hesitation word in natural speech. However, I don't think it's priggish to note that some people have verbal tics, such as inserting "like" or "sort of" at random points in almost every sentence, that detract from effective communication. I have a colleague who inserts "sort of" into most assertions, when he in fact means precisely what he is saying. I don't know what this has to do with Shakespeare's grave (and he can't turn over in it anyway because his remains are missing), but it is something people would be well advised not to do.

[(myl) Of course. But if someone is triggered by one hedge, filler, or discourse particle every few hundred (or thousand) words? Very few speakers are going avoid annoying them, if they're honest about it.]

Yuval said,

October 6, 2022 @ 7:29 am

From my neck of the woods I'd say you're wrong—Hebrew Twitter bursts every what seems like 3-4 days from yet another such peevester airing out the same tired peevish takes.

[(myl) Interesting. I don't see that on the English side. Is Twitter just guiding me away from much things, given my (limited) history on the site? Or is there a (current) language/culture difference here?]

bks said,

October 6, 2022 @ 7:55 am

With the universality of the Internet, it's become trivial to refute prescriptivist peeving. When Strunk&White ruled, it was an uphill battle.

Roscoe said,

October 6, 2022 @ 8:32 am

Speaking of bygone phenomena, how many people still use the expression “to turn over in one’s grave”? (I thought it had been eclipsed long ago by “to spin in one’s grave.”)

Minivet said,

October 6, 2022 @ 8:33 am

Back in the 2000s, with _Eats, Shoots, & Leaves_ a symptom, it was pretty popular among young, educated people to pounce on perceived bad English.

Since then, there has been a turn in internet culture (in the same generation) toward descriptivism and, more generally, kindness as default. Look at XKCD recovering from the old online trend to dismiss "sportsball"; I understand the popular podcast MBMBaM also exemplified this attitude shift over its run.

I include myself in both of the patterns above, by the way. I can't speak as much to where Zoomers are; it is probably also true that now the pouncing is more often political.

Terry K. said,

October 6, 2022 @ 9:33 am

@Roscoe

Google Ngrams shows "spinning in his grave" and "turn over in his grave" as now about equal (as of 2019), and these ahead of "spin in his grave" and "turning over in his grave". Or, put differently, in constructions with the -ing form, spinning is more common, but for constructions with the plain form, turn over is more common. Somewhat similar (but not identical) for "her grave" and "their graves".

I think the grammar difference relates the the semantic difference between a one time thing (turn over) versus something continuous or repeated continuously (spinning).

Philip Anderson said,

October 6, 2022 @ 2:08 pm

Being pedantic, if someone talks about ‘like’ being used “so many times“, it must be used more than once to count.

@Michael M

Re your first point, in my experience most peevers are far from left-wing and not bothered about offending others. Your second point is certainly true, but not really any different. I think there are fewer of them, and spread more thinly, if not just talking to each other in closed groups.

Jonathan Smith said,

October 6, 2022 @ 2:46 pm

Targets may shift over time… rage (whether or not expressed) at perceived dumb-indicative language errors of others may be a constant :D re: this topic, I recently hate the New Yorker's comma-enclosed quotative like, which Google confirms must be editorial policy:

Jun 6, 2022 — "She was, like, 'I'm just here.'"

Apr 11, 2022 — "She was, like, 'Oh, shut up already. […]'"

Mar 21, 2022 — "She was, like, 'I will fucking stop at nothing.'"

Mar 13, 2022 — "[…] she was, like, 'This is the strangest experience I've ever had. […]'"

Feb 20, 2022 — "She was, like, 'We're not coming back here ever again […]'"

Jan 17, 2022 — "So I'm sure she was, like, 'Great, grow up into that.'"

Nov 22, 2021 — "[…] she was, like, 'Shit, I've told her she can do anything she wants […]'"

NYT, etc., do this correctly: "she was like, [quote]" :P

Rick Rubenstein said,

October 6, 2022 @ 4:49 pm

Are there any proven therapies available for folks like me who, despite seeing the light decades ago, can't keep from wincing at "violations" of prescriptivist rules ingrained (mostly self-ingrained) during childhood? I want to be totally unfazed by "The team with the bigger amount of people has an advantage," but man, it's hard. (Not actually serious, but it's certainly true. Unlearning is tough.)

Mark Young said,

October 6, 2022 @ 7:06 pm

@Roscoe, @Terry K.

If I'm reading this correctly, then turn[ing] in his grave is more common than either turn[ing] over in his grave or spin[ning] in his grave.

And my preferred roll[ing] over in his grave is less common than I expected.

https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=roll_INF+in+his+grave%2Cturn_INF+over+in+his+grave%2Croll_INF+over+in+his+grave%2Cspin_INF+in+his+grave%2Cturn_INF+in+his+grave&year_start=1800&year_end=2019&corpus=26&smoothing=3&direct_url=t3%3B%2Croll_INF%20in%20his%20grave%3B%2Cc0%3B%2Cs0%3B%3Brolling%20in%20his%20grave%3B%2Cc0%3B%3Broll%20in%20his%20grave%3B%2Cc0%3B%3Brolled%20in%20his%20grave%3B%2Cc0%3B%3Brolls%20in%20his%20grave%3B%2Cc0%3B.t3%3B%2Cturn_INF%20over%20in%20his%20grave%3B%2Cc0%3B%2Cs0%3B%3Bturn%20over%20in%20his%20grave%3B%2Cc0%3B%3Bturning%20over%20in%20his%20grave%3B%2Cc0%3B%3Bturned%20over%20in%20his%20grave%3B%2Cc0%3B%3Bturns%20over%20in%20his%20grave%3B%2Cc0%3B.t3%3B%2Croll_INF%20over%20in%20his%20grave%3B%2Cc0%3B%2Cs0%3B%3Broll%20over%20in%20his%20grave%3B%2Cc0%3B%3Brolling%20over%20in%20his%20grave%3B%2Cc0%3B%3Brolled%20over%20in%20his%20grave%3B%2Cc0%3B%3Brolls%20over%20in%20his%20grave%3B%2Cc0%3B.t3%3B%2Cspin_INF%20in%20his%20grave%3B%2Cc0%3B%2Cs0%3B%3Bspinning%20in%20his%20grave%3B%2Cc0%3B%3Bspin%20in%20his%20grave%3B%2Cc0%3B%3Bspun%20in%20his%20grave%3B%2Cc0%3B%3Bspins%20in%20his%20grave%3B%2Cc0%3B.t3%3B%2Cturn_INF%20in%20his%20grave%3B%2Cc0%3B%2Cs0%3B%3Bturn%20in%20his%20grave%3B%2Cc0%3B%3Bturning%20in%20his%20grave%3B%2Cc0%3B%3Bturned%20in%20his%20grave%3B%2Cc0%3B%3Bturns%20in%20his%20grave%3B%2Cc0#

Tom Dawkes said,

October 7, 2022 @ 6:27 am

For a defence of "like" listen to https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m001b41g

Michael Rosen talks to Carmen Fought "a Californian Valley Girl, born and bred and she's, like, there's nothing wrong with using 'like'."

[(myl) Indeed. And as Carmen points out, an analogous use in Old English is what led to the modern adverbial ending -ly. And the use of like as "mild intensifier" or "filler" also has a long history — some citations from the OED include

1778 F. Burney Evelina II. xxiii. 222 Father grew quite uneasy, like, for fear of his Lordship's taking offence.

1840 T. De Quincey Style: No. II in Blackwood's Edinb. Mag. Sept. 398/1 Why like, it's gaily nigh like, to four mile like.

1929 ‘H. Green’ Living vi. 57 'E went to the side like and looked.

1966 Lancet 17 Sept. 635/2 As we say pragmatically in Huddersfield, ‘C'est la vie, like!’

]

Philip Anderson said,

October 7, 2022 @ 6:27 am

The expression I’m familiar with is (basically) “if X were alive to hear this, he would turn in his grave”. Spinning is just non-stop turning, but some people seem to have adopted the extended joke as the norm.

Benjamin E. Orsatti said,

October 7, 2022 @ 7:22 am

I had always interpreted "turning in one's grave" in the sense of "rotting", i.e., as milk "turns", as if some terrestrial offense had been so grievous as to actually accelerate the process of decomposition with respect to one who might have been especially sensitive to such an offense in life. This may have been an instance of jumping straight to zebras and missing the horses entirely.

Benjamin E. Orsatti said,

October 7, 2022 @ 7:25 am

Also, can we stop beating up on poor Philip Taylor? The post was _literally_ asking, "where have all the prescriptivists gone?", and when one pops his head up, he gets "whack-a-moled" with "irrelevant and obnoxious". Let's play nice.

Y said,

October 7, 2022 @ 8:53 am

While we are on peeving, can we (or rather, Prof. Liberman) resist the temptation to follow in the sarcastic devaluation of the verb "to trigger", in the manner of conservative baiters?

Bloix said,

October 7, 2022 @ 10:43 am

I like Philip Taylor! He's courteous, clear, opinionated, and often amusing. And as an example of a widely held point of view on English usage, he's educational. See for example my exchange with him here:

languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nil/?p=56516#comments.

A few decades ago, I happened to come across a copy of the first edition of Fowler's (1926) in a bookshelf, and I was astonished at the fine distinctions of meaning and usage that, apparently, were required in the journalistic, professional, and academic writing of a century ago. Here's Fowler on masterful vs. masterly:

"In spite of the excuse that such anarchy affords to the heedless, 'a pale, shimmering, altogether masterful watercolor' remains both ludicrous and wrong."

As Jesse Sheidlower has informed us, the masterful/masterly distinction has no discernible basis in historical usage. Fowler seems to have invented it. theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1996/12/elegant-variations-and-all-that/376744/

Good to know! And yet Fowler is still fun and educational. What a pleasure it would be to argue with him!

More often than not, I disagree with Philip Taylor. But what's the point of a comment thread if not to air disagreements and to argue them out? Otherwise, it's just cheerleading.

Bloix said,

October 7, 2022 @ 12:19 pm

PS – to myl – the OED does not sanction usage. It's not prescriptive, and "aims to cover the full spectrum of English language usage, from formal to slang, as it has evolved over time." Your examples of "like" as a filler or intensifier in the OED are all from reproduced dialogue in which the speaker is either rural, working class, or urban tradesman.

For example, in your first OED quotation, from the epistolary novel Evelina, the speaker is the adult son of a London silversmith who speaks a slangy and presumably cockney English as reproduced by Evelina, who dislikes him and his family: "Goodness, Miss, we were in such a stew, us, the servants, and all, as you can't think … [T]he footmen said they'd go and tell his Lordship .. So then Father grew quite uneasy like, for fear of his Lordship's taking offense .. so he said I should go this morning and ask his pardon, for cause of having broke the glass."

Note that not only is the English non-standard and full of slang ("Miss" without a name as a form of address, "such a stew as you can't think," "for cause of having broke"), but the character's morals are low (he is prepared to admit that he damaged the lord's property only because his responsibility was about to be reported by the servants). "Uneasy like" is of a piece with his tradesman character.

So, yes, "like" as intensive or filler is old. So is ain't. So is axe for ask. All are stigmatized, for good or ill.

Richard Hershberger said,

October 7, 2022 @ 3:36 pm

I don't think that language peeving has gone away, but what specific peeves are in fashion is a moving target. Read a 19th century usage manual such as Richard Grant White wrote and it can be hard to figure out what he is complaining about. Go forward a few decades and we can understand a complaint about "contact" as a verb, but really only by analogy with similar complaints we see today, not because anyone gives a second thought to this usage. The '60s gave us complaints about sentence adverb "hopefully." That had a good run, but by the '90s such complaints were pretty threadbare.

What are some current complaints? The purported which/they distinction will still get a rise, when someone happens to notice it, but I think this is on the down side. But suggest that the Oxford comma is not really a big deal either way and see the response!

Terry Hunt said,

October 7, 2022 @ 9:07 pm

@ Bloix — Though a decade less venerable than Philip Taylor, I must confess that I'm with Fowler on this one.

To me "masterly" means "exemplifying the skill of a master of the art or craft in question", while "masterful" means "exhibiting the dominating demeanour typical of a master towards a servant (or other social inferior)".

Clearly there can be circumstances where both may be applicable, perhaps leading to confusion of the two, but equally there are circumstances where only one is appropriate, such as (I think) in Fowler's example. Perhaps, as you say, there was originally no distinction between the two (or perhaps confusion between them goes back a long way), but language evolves and useful distinctions of meaning can emerge, in which case why not nurture them?

Y said,

October 7, 2022 @ 9:34 pm

What happened to all the, like, prescriptivists?

Now that I think about it, I must peeve against the use of like in the middle of a noun phrase.

C said,

October 8, 2022 @ 11:40 am

Perhaps in the 19 years Language Log has been dispensing linguistic knowledge and insight it has contributed to a cultural awareness, and self-awareness, of peeving.

Philip Taylor said,

October 8, 2022 @ 1:16 pm

That is an interesting point, C, and perhaps one worthy of investigation. Although I have not been a reader of Language Log for the entire duration of its existence, I have perhaps been reading it for about half of that time, and I do not personally feel that I am any less inclined to peeve, if that is the correct term, than I was at the outset. In fact, given Mark's original question "Where have all the prescriptivist peevers gone?", I cannot say, since I regard myself more as a proscriptive peever than a prescriptive one. In other words, I do not believe that I have a God-given right to tell others how they should speak (or write) but I do believe that I have a right (most certainly not God-given) to pass judgement if I believe that they are wrong. Justifiable or not, I will do my d@mndest never to end a sentence with a preposition, and I feel mildly irritated if others do. Similarly, I would not, in a million years, ever write "gonna" or "wanna", and my irritation on seeing those in print far exceeds my irritation on encountering a trailing preposition. To fellow humans I would normally say "it is I", but to my cat I invariably say "it's only me". I am, perhaps, one of the few people still alive who mourn the passing of the Society for Pure English ("SPE") but while composing this comment I learned for the first time of the existence of the Queen's English Society — I shall now set out to learn more about this organisation, whose aims [1] I believe I share.

Chester Draws said,

October 8, 2022 @ 3:03 pm

As if to prove Michael M right, at least in part, Ioffe's response was to make a political statement about men. That's where most of the peeving is now.

Philip Anderson is right also, of course, in that peevers tend to be conservative (not right-wing). However their access to media is thereby greatly diminished. The higher brow media are now solidly liberal (in the US sense) and not much interested in conservative issues. and the right wing media is populist, so uninterested in annoying their readers.

The few instances of conservative and not populist media, say The Spectator, continue to peeve.

Brett said,

October 8, 2022 @ 5:42 pm

I am now puzzled as to what Philip Taylor thinks proscribe means.

Levantine said,

October 9, 2022 @ 2:14 am

Sorry to tease you, Philip Taylor, but it seems you’re not too bothered by dangling modifiers (“Justifiable or not, I . . .”). Few usages really irk me, but dangling modifiers are among them, along with the hypercorrect use of “I” instead of “me”.

Philip Taylor said,

October 9, 2022 @ 2:21 am

Brett — to proscribe is to say "thou shalt not"; to prescribe (in the linguistic rather than the phamaceutical sense) is to say "thou shalt".

Viseguy said,

October 9, 2022 @ 2:28 am

@Levantine: I'm gonna rush to Philip Taylor's defense — because I suspect he meant to write "Justifiably or not" — even if it means irritating him by using a construction he wouldn't put up with.

Philip Taylor said,

October 9, 2022 @ 5:40 am

Ah, Churchill, how wise thou wert — "by using a construction up with which he would not put" … (And no, I did not miss the g*nn* — I just forced it to the back of my mind, with considerable effort).

As to "justifiable" v. "justifiably", it was not my actions to which I was referring, but rather to the (proscriptive) rule — "Thou shalt not end a sentence with a preposition". But of course I failed make this clear in the casting of my sentence — mea culpa.

LW said,

October 9, 2022 @ 3:54 pm

i'm surprised to read (pace Bloix) that '"Miss" without a name as a form of address' could be considered 'non-standard or slang'. i've always understood this as a fairly standard, polite construct when addressing someone the speaker isn't acquainted with, similar to (now obsolete) 'Master' when addressing a young man.

Philip Taylor said,

October 9, 2022 @ 4:42 pm

I would go along with LW here. "Miss" is a standard form of address to a young single female schoolteacher by members of her class, is a standard way of addressing an young female by (e.g.,) a shop-keeper, a ticket clerk a policeman and so on, and off-hand I cannot think of a situation in which it would be considered 'non-standard or slang', although I am certain that such situations must exist.

jaap said,

October 10, 2022 @ 6:01 am

My pet peeve is the use of "I mean" as a filler, especially if they're the first works someone says in a conversation. I'm no doubt oversensitive to it, but the problem is that I use it myself so I can't even complain about it.

jaap said,

October 10, 2022 @ 6:02 am

*words*

Philip Anderson said,

October 10, 2022 @ 7:03 am

When I was at school, “Miss” was the standard way to address any female teacher, married or single – the equivalent of Sir. I suspect that Philip Taylor’s memories go back to a time when women were expected to give up their jobs when they married.

Addressing a woman as plain “Mrs” would have been rude.

Philip Taylor said,

October 10, 2022 @ 10:49 am

Not quite old enough to remember those days, fellow Philip, but although I know that my divinity teacher at the age of 10 was Mrs Bishop, I have no recollection of how we addressed her, if indeed we did address her as anything other than "Mrs Bishop". Certainly not just "Mrs", but very doubtful that we would have addressed a married teacher of her age as "Miss". Any fellow Deansfieldians here to add to this ?

Bloix said,

October 10, 2022 @ 12:38 pm

The use of Miss, Mrs., Madam and Ma'am from the 18th through the 20th c is complicated, with changes over time and distinctions based on social class, region, and age. I used to think I had a handle on it – until we had a set-too about "miss" at Language Hat over a novel called Miss Cayley's Adventures (1899), by Grant Allen. I did some research at that time and here's what I think: In the passage I quoted, at the time of the novel (1778), the speaker should have said either "Miss Anville" or "ma'am." A servant would call the mistress "miss" but a non-servant who intended to show respect wouldn't have used it. The whole passage has an air of cringing servility about it and the use of "miss," IMHO, is intended to contribute to that impression.

I'm happy to be corrected. But the point relevant to this thread isn't affected: Evelina is reporting this anecdote in detail to demonstrate the low manners and morals of the quoted speaker. Therefore his verbal use of "like" as an intensive isn't reliable evidence that the usage was considered standard in the late18th c.

Philip Taylor said,

October 11, 2022 @ 4:51 am

Well, it is interesting to note that Evelina herself says "not one of the party call me by any other appellation than that of Cousin or of Miss", but I know insufficient of the mores of that period to know whether she might reasonably have taken offence at being called "Miss" by young Branghton.

LW said,

October 11, 2022 @ 2:47 pm

Philip Anderson: i am (just about) still under 40 years old, and i've been called 'Miss' before, by a flight attendant on a plane. so i'm not sure someone needs memories as far-reaching as Philip Taylor's to recall that usage.

i will admit that the only reason i remember that example to begin with is that it seemed rather unusual to be addressed that way, but i'm not sure how else he might have phrased it. i feel like the most common approach nowadays would be to just say "Excuse me–?", but perhaps that's too informal for some contexts.

to be honest, i find the whole idea of these honorifics a bit confusing. i still receive plenty of post address to to "Miss " because, not being married, that seems like the most appropriate option to choose from the list of titles they give you. but i'm not sure if there's meant to be an age limit on being a 'Miss'. should i be 'Ms.' instead? or perhaps 'Mx.'? to be honest, i'd be happy if we just did away with the whole thing.

Philip Anderson said,

October 13, 2022 @ 7:08 am

@LW

I think you misunderstood me. Miss was, and is, unexceptional (and in my school was used for female teachers of any age).

My memories comment referred to a period when most married women did not work (so a female teacher was probably unmarried). My mother didn’t work after having children, although that was becoming rarer.