A linguist walks into a bear

« previous post | next post »

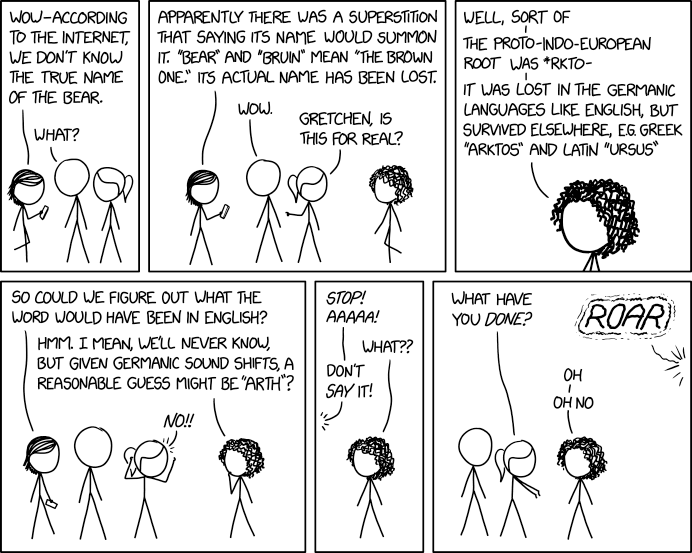

Today's xkcd:

Mouseover title: "Thank you to Gretchen McCulloch for fielding this question, and sorry that as a result the world's foremost internet linguist has been devoured by the brown one. She will be missed."

Credit for the post title goes to Matthew Hongoltz-Hetling, A Libertarian Walks Into a Bear: The Utopian Plot to Liberate an American Town (And Some Bears).

S Frankel said,

November 4, 2020 @ 8:45 am

Yikes – 'arth' means 'bear' in Welsh. What just happened? Loan from a non-existent English word?

Narmitaj said,

November 4, 2020 @ 9:29 am

I wondered about Arthur.

"The meaning of this name is unknown. It could be derived from the Celtic elements artos "bear" combined with viros "man" or rigos "king". Alternatively it could be related to an obscure Roman family name Artorius."

https://www.behindthename.com/name/arthur

Philip Taylor said,

November 4, 2020 @ 10:21 am

The GPC Online says :

which Google Translate renders as :

anhweol said,

November 4, 2020 @ 10:38 am

arth

[e. prs. H. Lyd. Arth(mael), Gwydd. C. art: < Clt. *artos (cf. Llad. Gâl Deae Artioni (dadiol)) < IE. *r̥tk̂o- < *ər̥tk̂o- ‘arth’, Llad. ursus, Gr. ἄρκτος]

my translation:

= Old Breton personal name Arth(mael), Middle Irish art< Celtic *artos (compare Gaulish Latin Deae Artioni (dative) < Indo-European *r̥tk̂o- < *ər̥tk̂o- ‘bear’, Latin ursus, Greek ἄρκτος]

But while this is good Welsh is it really the expected Germanic? Don't syllabic rhotics become *ur in Germanic?

S Frankel said,

November 4, 2020 @ 10:40 am

Google Translate was lol funny – Llad is Lladin(Latin) not Lladd (thief).

Personal name Old Breton Arth (mael) [don't know what that means in Old Breton), Middle Irish art: < (Common?)Celtic *artos. The rest should be obvious.

So, how'd a Common Celtic word end up looking like a Germanic one?

Scott P. said,

November 4, 2020 @ 11:25 am

"The meaning of this name is unknown. It could be derived from the Celtic elements artos "bear" combined with viros "man" or rigos "king". Alternatively it could be related to an obscure Roman family name Artorius."

The Artorius derivation has very little behind it.

Nick Z said,

November 4, 2020 @ 3:45 pm

Even allowing for simplification due to the fact that the PIE word for 'bear' has more than the average amount of irritating diacritics, *rkto- is rather inaccurate: *hrtko- would be better (initial laryngeal and -tk- sequence guaranteed by Hittite hartakka-). Welsh arth, Middle Irish art are just the regular results of this sequence. The syllabic *r would indeed be expected to give *ur- in Proto-Germanic, not *ar-.

GEOFF Nathan said,

November 4, 2020 @ 4:09 pm

I notice that, mercifully, nobody has commented on Mark's headline.

John Shutt said,

November 4, 2020 @ 6:50 pm

@Nick Z: So, does that mean the missing English word would be a homophone of "earth"?

martin schwartz said,

November 4, 2020 @ 11:12 pm

Like Gretchen and the other characters, the Indo-European here is rather,

uh, sketchy. We're spared a stick-figure bear. As to reconstruction, I'm with Nick Z here. But: is Hitt. hartakka- really 'bear'?

It's usually said to be, however I see on Internet where M. Weiss

has it as 'tree-climbing animal' and C. Watkins as "wolf'. Others as 'big/dangerous animal'. One should also have a look at Blazek 'IE bear"

in Historische Sprachforschung. I dunno, just sayin'.

Martin Schwartz

cliff arroyo said,

November 5, 2020 @ 2:22 am

IIRC Slavs also had the bear-naming taboo which is why Slavic words for bear like medvěd (Czech) or медведь (Russian) mean 'honey knower' (I've also seen 'honey eater' but knower seems more likely)

In Polish the initial m became an n niedźwiedź and in Ukrainian the order is reversed ведмідь…

What would the old IE root look like in modern Slavic languages?

Andreas Johansson said,

November 5, 2020 @ 3:02 am

@John Shutt:

Acc'd the Blazek paper martin schwartz mentions, the Germanic form of the root should be urh- (and is possibly attested in old anthroponyms). I'm not sure what that would have yielded in modern English, but definitely not a homophone of "earth".

Renee said,

November 5, 2020 @ 3:05 am

To all discussing "arth" and "Arthur", Gretchen McCulloch posted the following on Twitter

"I did point out the arth/Arthur thing in Celtic languages when Randall showed me the draft of this comic a few days ago but alas not everything can fit in one comic"

– https://twitter.com/GretchenAMcC/status/1323890454505705473

Adam F said,

November 5, 2020 @ 4:23 am

Does that count as performative language?

Nelson Goering said,

November 5, 2020 @ 6:27 am

The vowel in Germanic would certainly be *u, not *a.

The consonants are much harder. Blažek tries to generalize from word-initial treatments of *DG- > *G- to conclude that medially we should expect *tḱ to come out as *ḱ (> Germanic *h, /x/). This is not appropriate, given the very different syllabic contexts: *dʰǵʰ-, etc., make for a very complex onset that does not observe sonority sequence, while *h₂ŕ̥t.ḱos has no difficulties of this sort.

The unfortunate answer is that we just don't know what the regular outcome would be. One possibility (which I think Ringe would favour) would be to see metathesis, as in Greek and (probably) Celtic, occurring after the automatic insertion of a sibilant (or maybe palatal) element after the dental: *tḱ > *tsḱ > *ḱts, maybe ending up as something like *hs — Blažek's *urhsaz, but by a different means. (I'm much more skeptical than Blažek that we have any positive evidence for this in those personal names; the possibility of a connection with Latin ursus seems too high to rule out.)

If we don't want to assume metathesis, part of the question is what happens to the *t. If there is any parallel with purely dental clusters, we might get *tḱ > *tsḱ > *sk, for PGmc *urskaz.

Or maybe *tḱ developed in some other way entirely. It's just hard to say. The possible relevant evidence (the etymologies of German Dechsel and related elements, for instance) has its own complications, and the overall body of data within Germanic is extremely small.

So, definitely not 'arth', but what the right alternative would be is very hard to say for sure.

Andreas Johansson said,

November 5, 2020 @ 6:34 am

@Nelson Goering:

Assuming PGmc *urhsaz or *urskaz, what would the Modern English descendants be?

Benjamin E. Orsatti said,

November 5, 2020 @ 8:33 am

Interesting thing about bear taboos — in some cultures, the brown honey-eater is a ne'er-to-be-named Færie; and in others, well, they adopt him as a totem. — Ben E. Orsatti>Orsatto>Orsato>Orsa>Ursa>Ursus>Orssos>*h₂ŕ̥ḱþos>h₂ŕ̥ḱtos>h₂ŕ̥tḱos>*semiotic ostentive grunt*.

Nelson Goering said,

November 5, 2020 @ 11:51 am

"Assuming PGmc *urhsaz or *urskaz, what would the Modern English descendants be?"

The second would probably have ended up as *orsh (*orx would be a dialectal possibility).

The first one is trickier, since that exact sound sequence isn't terribly common, and I'm not coming up with useful parallels off the top of my head. Something like *orx would seem reasonable, though if we had some simplification of the cluster we might end up with something like *orse instead.

There are other outcomes we could speculate about, too. If we had metathesis but no assibilation, we could get PGmc *urhtaz, which should come out as *rought, for instance.

Michael Watts said,

November 6, 2020 @ 5:26 am

I've seen this referred to as a well-known "taboo" elsewhere, too. I've never understood why. Is there any evidence that the common word for bear changed for reasons of a taboo on the earlier word? Why don't we talk about the Romance taboo on referring to horses, or the English taboo on referring to dogs?

David Morris said,

November 6, 2020 @ 7:10 am

I called my childhood toy bear Bruin (even though it was light to medium blue) on the grounds that everyone had a Teddy and I wanted something different. At least that's what I thought, but I've just checked my mother's diary from my childhood, and her first reference to it was when I was about 18 months, so it certainly wasn't my idea.

Philip Taylor said,

November 6, 2020 @ 8:54 am

… and mine was called "Brumas", named after a baby polar bear born in London Zoo on 27th November 1949 (2½ years after my own birth). Brumas (the real one) was named after his keepers, Bruce and Sam.

Tom Dawkes said,

November 6, 2020 @ 10:05 am

medvěd and медведь are divided as medv-ěd and медв-едь, not as med-věd (Czech) or мед-ведь. The meds- element is cognate with Greek methu, which is cognate with English 'mead' — a honey drink — and may be an adjective meaning 'sweet', and the ed- is cognate with English 'eat'.

Andrew Usher said,

November 6, 2020 @ 8:17 pm

So, are they wrong about the t > th sound change operating here, or is it just that the environment for it could never arise? I can't think right now of any other examples in a cluster, but there must be some (in 'earth' itself the PIE root is said not to have had 't' at all). I guess the idea behind it was that the /k/ in /rkt/ would drop (as in a common pronunciation of 'arctic' which of course is from that root), and then it could change to /rθ/ giving our arth/orth/urth (whatever the vowel).

Also (replying to the comment by Martin Schwartz) hartakka- doesn't have to mean 'bear' (synchronically), it only has to descend from the same root to act as a proof; I think the other meanings proposed aren't so distant as to make that unlikely.

k_over_hbarc at yahoo.com

Philip Taylor said,

November 7, 2020 @ 3:13 am

Does /ˈɑrːk tɪk/ -> /ɑrː ˈtɪk/ result from /k/-dropping, or does it result from confusion with /ɑrː ˈtɪk/ = "artic" = "articulated lorry" ? To my mind, the latter seems definitely possible.

Nelson Goering said,

November 7, 2020 @ 3:40 am

"So, are they wrong about the t > th sound change operating here, or is it just that the environment for it could never arise?"

If we had an early *t, it would indeed become Proto-Germanic *θ (usually notated *þ), which would (in most positions) survive to be spelled today as 'th'.

The problem is that the original cluster was *tḱ, and there is no evidence at all that this would have been simplified specifically to *t in the very early historical phonology of Germanic. It is not phonetically impossible for this to have taken place, but there are many phonetically plausible changes one could apply to such a cluster, and we have zero evidence that this particular one took place.

"or does it result from confusion with /ɑrː ˈtɪk/ = "artic" = "articulated lorry" ?"

I grew up in an area of the US where many people said 'arctic' with deletion of the first /k/, but no one had ever heard of an 'articulated lorry', much less used a clipped form of the term.

Michael Watts said,

November 7, 2020 @ 4:54 am

This seems unlikely to me, since the pronunciation is standard in America, while I assume well over 99.99% of Americans live and die without ever hearing of an "artic".

Assuming you mean one truck dragging multiple trailers (I'm not sure what else a jointed truck would mean…?), I'd just call that a semitruck.

Andreas Johansson said,

November 7, 2020 @ 6:29 am

Acc'd etymonline and Wiktionary, the medial /k/ of ModEng "Arctic" is a conscious restoration, the word having originally been borrowed from Old French artique. So modern pronunciations without it probably simply continue the Middle English form, having missed the pedant train.

Modern French has similarly restored arctique, but reduced froms persist in other Romance languages, like Spanish ártico.

Andrew Usher said,

November 7, 2020 @ 9:15 pm

I knew the history but was trying to simplify things – the cluster in 'arctic' was reduced by eliminating the medial consonant, whether it was in English or in Romance solely. I do not know if that Latin 'ursus' had this reduction is its prehistory or not.

Michael Watts:

No, an 'artic' does not need to have multiple trailers. Just one trailer and the cab make an 'articulation' – I agree Americans would generally call this a 'semi-truck', though what it is 'semi' of I could not say.

We do though have in some places 'articulated buses', but that is never abbreviated (that I know of).

In any case the different stress and lack of any semantic overlap seem to exclude the possibility of arctic/artic interference, and the suggestion by Philip Taylor seems quite bizarre.

Jerry Friedman said,

November 8, 2020 @ 12:24 am

That sent me to the OED. The original form of the American "semi" (eighteen-wheeler) is "semi-trailer", and the definition is

"A road trailer that has a wheel system at the rear only and is coupled to a suitable tractor to form an articulated lorry. Frequently transferred, an articulated lorry made up in this way."

Joyce Melton said,

November 8, 2020 @ 1:34 am

I like the idea of "orse" being the imaginary descendat word of a PIE root. Because of the song, of course.

An orse is an orse, of course, of course…

Michael Watts said,

November 8, 2020 @ 3:23 am

In my understanding, a semitruck is literally half a truck. It has the engine but not the cargo space. (Instead, it is attached to an independent container which has cargo space but no engine.)

A semitruck is to a truck as a locomotive is to a hypothetical several-cars-long locomotive which isn't expected to drag anything behind it.

Michael Watts said,

November 8, 2020 @ 3:25 am

Commenting several times in a row in hopes of not getting censored for including links:

Here is a truck. It's all one piece.

Michael Watts said,

November 8, 2020 @ 3:26 am

Here is a semitruck. Notice anything missing?

Michael Watts said,

November 8, 2020 @ 3:27 am

We continue to call semitrucks "semitrucks" while they're hauling cargo, but I don't see anything especially unusual about that.

A. Barmazel said,

November 8, 2020 @ 12:50 pm

@cliff arroyo

> What would the old IE root look like in modern Slavic languages?

Wiktionary names Proto-Balto-Slavic *irśt, surviving today in Lithuanian irštvà, meaning “bear's den”; and Proto-Slavic *rьstъ.

Andrew Usher said,

November 8, 2020 @ 7:50 pm

Yes, that may be the origin of 'semi', I certainly agree. However –

The OED definition quoted by Jerry Friedman, though, says that the 'semi' was first the rear or trailer part. That seems about equally plausible on its face, but if the first form recorded was 'semi-trailer', would seem to be the right one.

In either case it's still strange the way it's used today – people's picture of a 'semi' is always a truck with trailer, both parts together, and if only one were meant, that would be specified explicitly. It has become, in other words, an idiom – a 'semi-truck' and a 'semi-trailer' together making up a 'semi', the literal meaning having thus vanished.

Michael Watts said,

November 9, 2020 @ 4:14 pm

I think this is mostly correct, but I'll point out that I found that semitruck picture by doing a google image search for "semitruck". I know that "semitruck" refers to the part with the engine, and that it's still called a semitruck while attached to cargo, but I know no word (personally) for the container being towed.

I might or might not feel the need to explicitly call out that a semitruck had nothing behind it; my gut says I often would. However, in many cases that would be because the lack of cargo was what made the semitruck interesting at all. This is probably fairly context-dependent. Completely agreed that the default picture includes the cargo container.

Philip Anderson said,

November 13, 2020 @ 12:58 pm

Old Breton Arthmael: Bear Prince.

Mael < maglo- was a common element in Celtic names, e.g. Welsh Maglocunos=Maelgwn and with the same hound-prince meaning Cynfael

ktschwarz said,

November 13, 2020 @ 8:20 pm

Michael Watts: "Why don't we talk about the Romance taboo on referring to horses, or the English taboo on referring to dogs?"

Good question. A possible answer from a comment at Language Hat's 2018 post on the bear word:

That would also apply to English "pig", originally a word for baby pigs, now including all ages and replacing the original PIE-descended "swine".