The difference between deformation and devoidness

« previous post | next post »

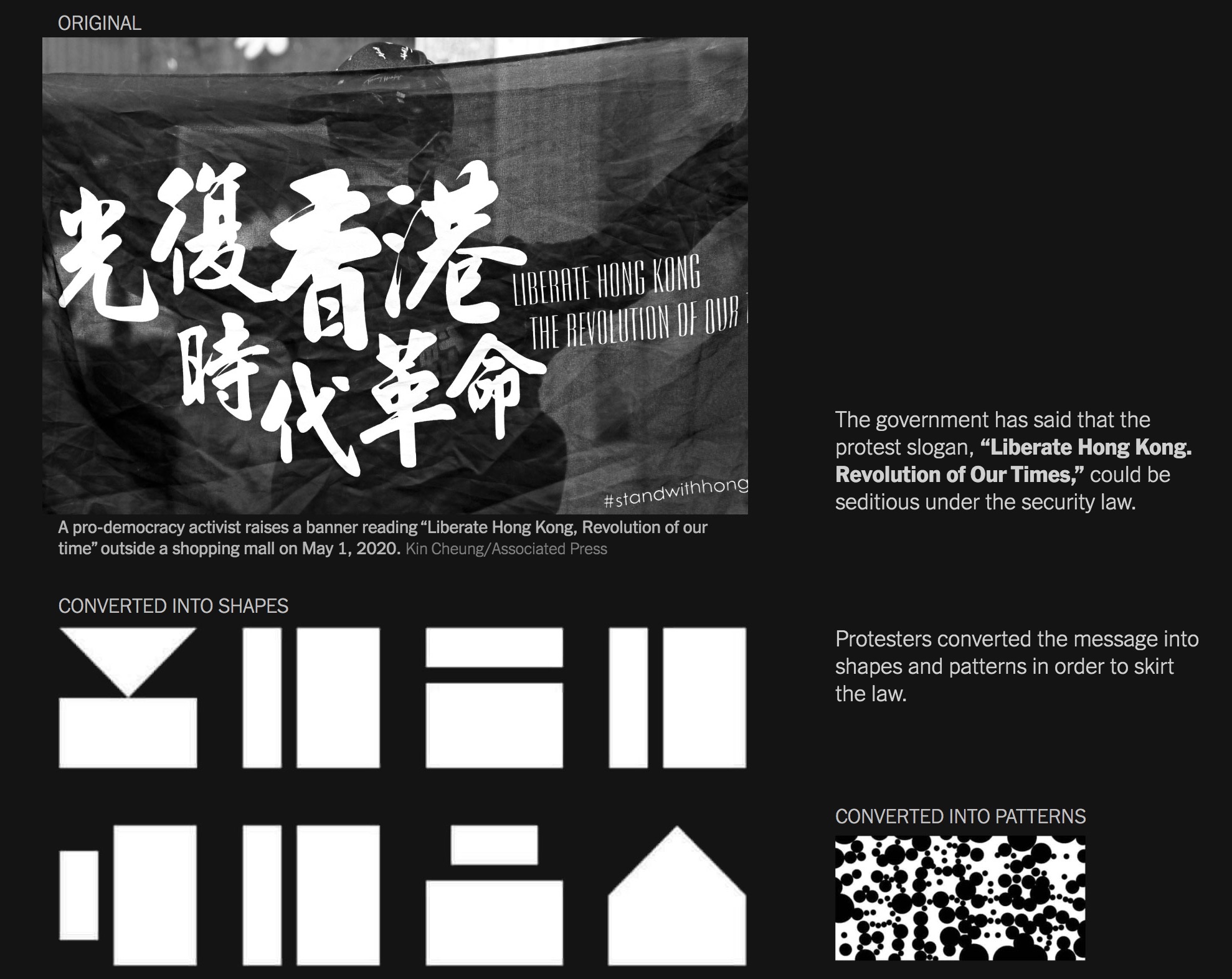

Final panel of this New York Times article: "What You Can No Longer Say in Hong Kong" (9/4/20), by Jin Wu and Elaine Yu:

The Chinese characters at the top left constitute the protest slogan that we have been following for the last year and more:

guāngfù Xiānggǎng

shídài gémìng

gwong1fuk6 Hoeng1gong2

si4doi6 gaak3ming6

光復香港

時代革命

Liberate Hong Kong,

The revolution of our times

Chinese Wikipedia

English Wikipedia

As the CCP authorities continued to clamp down on dissent in Hong Kong, they increasingly censored open expression of this slogan and arrested those who proclaimed it. To circumvent censorship and arrest, Hong Kong dissidents resorted to various kinds of graphic deformation of the slogan, a process that is reflected in the above panel and that we have documented on Language Log (see the "Selected readings" below).

When such deformation is carried to the extreme, here's what you are left with:

Pro-democracy lawmakers in July held up blank placards in Hong Kong's legislature to protest restrictions on speech.Vincent Yu/Associated Press

This is the first panel in the NYT article cited at the beginning of this post.

Last two paragraphs of the article by Jin Wu and Elaine Yu:

But there are concerns that even such workarounds may be deemed illegal.

“The police were giving warnings to young protesters holding blank signs,” said Claudia Mo, a pro-democracy lawmaker. “They are trying to say: ‘If we say you’re expressing a criminal opinion, then that’s it, because we are the law.’”

Even if you say nothing — i.e., if your deformation has devolved into nothingness / emptiness — the government may hold that that is an expression of criminal opinion.

The distinction between freedom of speech and its absence is stark. How do we measure it? How do we experience it? How do we express it? One moment we may have freedom of speech; the next moment it may disappear entirely.

That is what has happened recently in Hong Kong when the dark curtain of the National Security Law descended upon the former British colony and dependent territory (1841-1997).

Selected readings

- "GFHG, SDGM" (7/7/20)

- "Vocabulary of Hong Kong protest slogans and new characters" (9/1/19)

- "Hong Kong protests: 'recover' or 'liberate'" (11/3/19)

- "Loose Romanization for Cantonese" (9/21/19)

- "Women's Romanization for Hong Kong" (9/17/19)

- "Hong Kong protesters' argot" (9/7/19) — includes a long list of relevant posts

- "Uppercase and lowercase letters in Cantonese Romanization" (5/28/20) — also includes a long list of relevant posts

- "Better said in Cantonese" (7/4/20) — also includes a long list of relevant posts

- "National Security Law eclipses Hong Kong" (6/2/20)

[h.t. John Rohsenow; thanks to Ben Zimmer]

Nathaniel Jacobs said,

September 5, 2020 @ 10:17 pm

It seems that they have been charged for the perlocutionary force of your actions. (Does holding up blank signs constitute a speech act? Can a non-speech act have perlocutionary force?)

Nathaniel Jacobs said,

September 5, 2020 @ 10:20 pm

What incredible creativity, resilience, and courage in the face of despotism.

Philip Taylor said,

September 6, 2020 @ 3:44 am

The content of the New York Times article: "What You Can No Longer Say in Hong Kong" is truly chilling, but the design and typography are superb, and the designer(s)/typographer(s) deserve an award for what is without doubt a magnificent exemplar of the very best of journalistic design.

Tom Saylor said,

September 7, 2020 @ 6:51 am

What about what you can no longer say in an American classroom?

No comment on Language Log from either Victor Mair or Mark Liberman on the case of USC professor Greg Patton, as academic freedom is sacrificed at the altar of BLM wokeness.

Victor Mair said,

September 7, 2020 @ 6:57 am

What?

Please see the recently posted "'That, that, that…', part 2" (8/28/20), which already has well over a hundred comments.

All the reports in the media, including the video of Prof. Patton pronouncing the Chinese word (nèige nèige nèige), derive from that Language Log post.

Michael Watts said,

September 10, 2020 @ 9:39 am

There's nothing even slightly unusual about this. Compare Tinker, in which American students were punished for expressing disagreement with the Vietnam War by wearing black armbands.

Chas Belov said,

September 13, 2020 @ 9:26 pm

I see comments are closed on the "That, That" threads.

Trevor Noah did an interview with Ronny Chieng on the "that, that" issue. While this is from the Comedy Channel so it needs to be taken with a grain of salt, it turns out this mistake could go in both directions.