From the American Association for the Advancement (?) of Science (?)

« previous post | next post »

The following is a guest post by Richard Sproat:

Regular readers of Language Log will remember this piece discussing the various problems with a paper by Rajesh Rao and colleagues in their attempt to provide statistical evidence for the status of the Indus “script” as a writing system. They will also recall this piece on a similar paper by Rob Lee and colleagues, which attempted to demonstrate linguistic structure in Pictish inscriptions. And they may also remember this discussion of my “Last Words” paper in Computational Linguistics critiquing those two papers, as well as the reviewing practices of major science journals like Science.

In a nutshell: Rao and colleagues’ original paper in Science used conditional entropy to argue that the Indus “script” behaves more like a writing system than it does like a non-linguistic system. Lee and colleagues’ paper in Proceedings of the Royal Society used more sophisticated methods that included entropic measures to build a classification tree that apparently correctly classified a set of linguistic and non-linguistic corpora, and furthermore classified the Pictish symbols as logographic writing.

But as discussed in the links given above, both of these papers were seriously problematic, which in turn called into question some of the reviewing standards of the journals involved.

Sometimes a seemingly dead horse has to be revived and beaten again, for those reviewing practices have yet again come into question. Or perhaps I should in this case say “non reviewing practices”: for an explanation, read on.

Not being satisfied by merely critiquing the previous work, I decided to do something constructive, and investigate more fully what one would find if one looked at a larger set of corpora of non-linguistic symbol systems, and contrasted them with a larger set of corpora of written language. Would the published methods of Rao et al. and Lee et al. hold up? Or would they fail as badly as I predicted they would? Are there any other methods that might be useful as evidence for a symbol system’s status? In order to answer those questions I needed to collect a reasonable set of corpora of non-linguistic systems, something that nobody had ever done. And for that I needed to be able to pay research assistants. So I applied for, and got, an NSF grant, and employed some undergraduate RAs to help me collect the corpora. A paper on the collection of some of the corpora was presented at the 2012 Linguistic Society of America meeting in Portland.

Then, using those corpora, and others I collected myself, I performed various statistical analyses, and wrote up the results (see below for links to a paper and a detailed description of the materials and methods). In brief summary: neither Rao’s nor Lee’s methods hold up as published, but a measure based on symbol repetition rate as well as a reestimated version of one of Lee et al.’s measures seem promising — except that if one believes those measures, then one would have to conclude that the Indus “script” and Pictish symbols are, in fact, not writing.

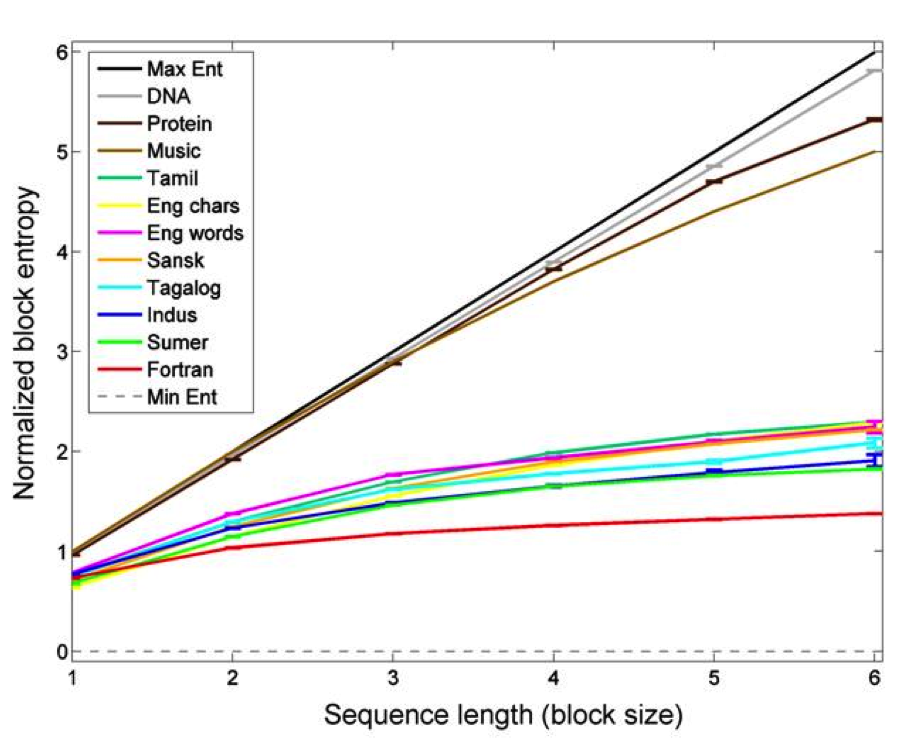

So for example in a paper published in IEEE Computer (Rao, R., 2010. Probabilistic analysis of an ancient undeciphered script. IEEE Computer. 43~(3), 76–80), Rao uses the entropy of ngrams — unigrams, bigrams, trigrams and so forth, which he terms “block entropy” — as a measure to show that the Indus “script” behaves more like language than it does like some non-linguistic systems. He gives the following plot:

For this particular analysis Rao describes exactly the method and software package he used to compute these results, so it is possible to replicate his method exactly for my own data.

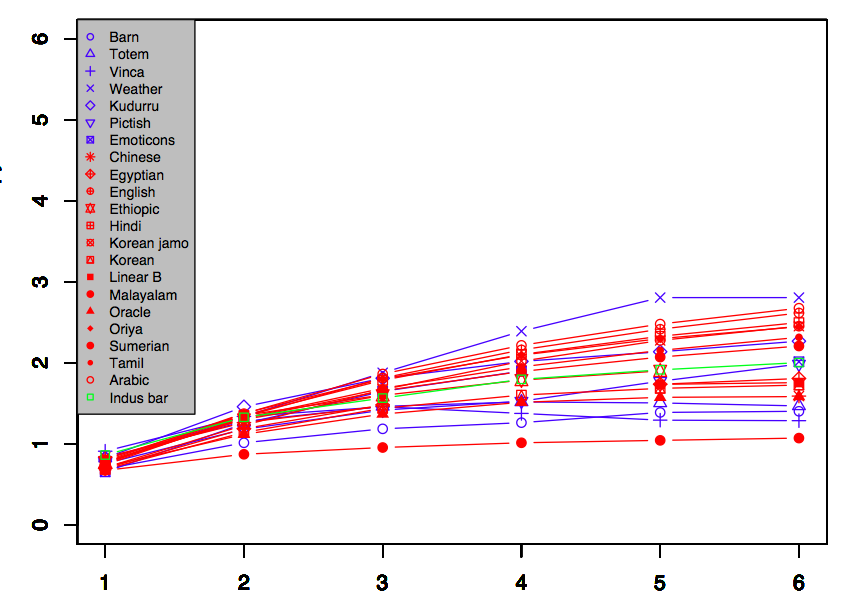

The results of that are shown below, where linguistic corpora are shown in red, non-linguistic in blue, and for comparison a small corpus of Indus bar seals in green. As can be seen, for a representative set of corpora, the whole middle region of the block entropy growth curves is densely populated with a mishmash of systems, with no particular obvious separation. The most one could say is that the Indus corpus behaves similarly to any of a bunch of different symbol systems, both linguistic and non-linguistic.

In this first version of the plot, I use the same vertical scale as Rao’s plot for ease of comparison:

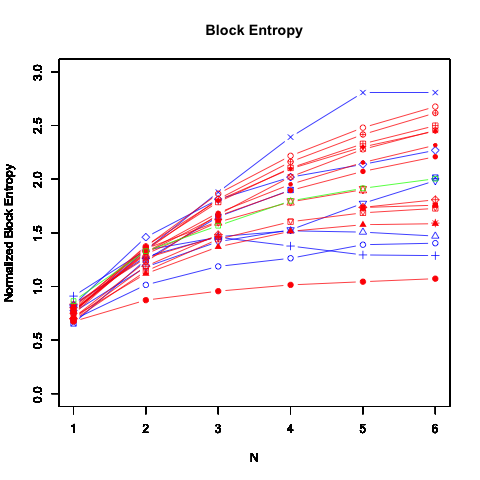

Here's a version with the vertical scale expanded, for easier comparison of the datasets surveyed — again, non-linguistic datasets are in blue, known writing systems are in red, and the Indus bar-seal data is in green:

With Lee et al’s decision tree, using the parameters they published, I could replicate their result for Pictish (a logographic writing system), but also it also classifies every single one of my other non-linguistic corpora — with the sole exception of Vinča — as linguistic.

One measure that does seem to be useful is the ratio of the number of symbols that repeat in a text and are adjacent to the symbol they repeat (r), to the number of total repetitions in the text (R). This measure is by far the cleanest separator of our data into linguistic versus nonlinguistic, with higher values for r/R (e.g. 0.85 for barn stars, 0.79 for weather icons, and 0.63 for totem poles), being nearly always associated with non-linguistic systems, and lower values (e.g. 0.048 for Ancient Chinese, 0.018 for Amharic or 0.0075 for Oriya) being associated with linguistic systems.

However this is partially (though not fully) explained by the the fact that r/R is correlated with text length, and non-linguistic texts tend to be shorter. This and other features (including Rao et al. and Lee et al.’s measures) were used to train classification and regression trees, and in a series of experiments I showed that if you hold out the Pictish or the Indus data from the training/development sets, the vast majority of trained trees classify them as non-linguistic.

To be sure there are issues: we are dealing with small sample sizes and one cannot whitewash the fact that statistics on small sample sizes are always suspect. But of course the same point applies even more strongly to the work of Rao et al. and Lee et al.

Where to publish such a thing? Naturally, since the original paper by Rao was published in Science, an obvious choice would be Science. So I developed the result into a paper, along with two supplements S1, S2, and submitted it.

I have to admit that when I submitted it I was not optimistic. I knew from what I had already seen that Science seems to like papers that purport to present some exciting new discovery, preferably one that uses advanced computational techniques (or at least techniques that will seem advanced to the lay reader). The message of Rao et al.’s paper was simple and (to those ignorant of the field) impressive looking. Science must have calculated that the paper would get wide press coverage, and they also calculated that it would be a good idea to pre-release Rao’s paper for the press before the official publication. Among other things, this allowed Rao and colleagues to initially describe their completely artificial and unrepresentative “Type A” and “Type B” data as “representative examples” of non-linguistic symbol systems, a description that they changed in the archival version to “controls” (after Steve Farmer, Michael Witzel and I called them on it in our response to their paper). But anyone reading the pre-release version, and not checking the supplementary material would have been conned into believing that “Type A” and “Type B” represented actual data. All of these machinations were very clearly calculated to draw in as many gullible reporters as possible. I knew, therefore, what I was up against.

So, given that backdrop, I wasn’t optimistic: my paper surely didn’t have such flash potential. But I admit that I was not prepared to receive this letter, less than 48 hours after submitting:

Dear Dr. Sproat:

Thank you for submitting your manuscript “Written Language vs. Non-Linguistic Symbol Systems: A Statistical Comparison” to Science. Our first stage of consideration is complete, and I regret to tell you that we have decided not to proceed to in-depth review.

Your manuscript was evaluated for breadth of interest and interdisciplinary significance by our in-house staff. Your work was compared to other manuscripts that we have received in the field of language. Although there were no concerns raised about the technical aspects of the study, the consensus view was that your results would be better received and appreciated by an audience of sophisticated specialists. Thus, the overall opinion, taking into account our limited space and distributional goals, was that your submission did not appear to provide sufficient general insight to be considered further for presentation to the broad readership of Science.

Sincerely yours,

Gilbert J. Chin

Senior Editor

It is worth noting that this is more or less exactly the same lame response as Farmer, Witzel and I received back in 2009 when we attempted to publish a letter to the editor of Science in response to Rao et al.’s paper:

Dear Dr. Sproat,

Thank you for your letter to Science commenting on the Report, titled "Entropic Evidence for Linguistic Structure in the Indus Script." I regret to say that we are not able to publish it. We receive many more letters than we can accommodate and so we must reject most of those contributed. Our decision is not necessarily a reflection of the quality of your letter but rather of our stringent space limitations.

We invite you to resubmit your comments as a Technical Comment. Please go to our New Submissions Web Site at www.submit2science.org and select to submit a new manuscript. Technical Comments can be up to 1000 words in length, excluding references and captions, and may carry up to 15 references. Once we receive your comments our editors will restart an evaluation for possible publication.

We appreciate your interest in Science.

Sincerely,

Jennifer Sills

Associate Letters Editor

We never did follow up on the invitation to submit a Technical Comment, but then we know very well what would have happened if we had.

So let’s get this straight: an article that deals with a 4500-year old civilization that most people outside of South Asia have never heard of is of broad general interest if it purports to use some fancy computational method to make some point about that civilization. Forget the fact that the method is not fancy, is not even novel, and is in any case naively applied and that the results are based on data that are at the very least highly misleading. But if a paper comes along that is based on much more solid data, tries a variety of different methods, shows — unequivocally — that the previous published methods do not work, and even reverses the conclusions of that previous work, then that is of no general interest.

I think the conclusion is inescapable that Science is interested primarily if not exclusively in how their publications will play out in the press. Presumably the press wouldn’t be that interested in the results of my paper: too technical, not good for sound bites. And certainly the conclusions might seem unpalatable: among other things it means that the earlier paper that Science did publish was wrong.

But then that’s what science is about isn’t it? Science advances sometimes by showing that previous work was in error. Science is published by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, but it’s hard to see science, much less advancement in their editorial policies.

More generally, why is it that in the past 5 years (at least), none of the relatively few papers that Science published in the area of language stands up to even mild scrutiny by linguists on forums such as Language Log and elsewhere? I have seen explanations to the effect that because they do not publish on language much, they don’t really have a good crop of reviewers for papers in that area. Certainly that does seem to have been true. The question is why it continues to be true: doesn’t an organization that claims to promote the advancement of science owe it to its readership to get qualified experts as peer reviewers for papers in an area that they cover; and to actually listen to the few qualified reviewers they do get (cf. here). If they aren’t prepared or aren’t able to do this, then perhaps it would be better if they got out of the business of publishing papers related to language entirely.

But then again we know what their real goal is, don’t we? We know that whenever they review a paper it’s always with an eye to what Wired Magazine or The New York Times are going to do with that paper. So when they see a paper that uses some computational technique to derive a result that “increases the likelihood” that India’s oldest civilization was literate; or a paper that claims to show evidence that we can trace language evolution back to Africa 70K years ago (see here); they see the obvious opportunity for publicity. Science gets yet another showing in the popular press, the lay reader will be duped by the dazzle of the technical fireworks that he or she does not understand anyway, and can in any case be expected to quickly forget the details of: All they might remember is that the paper looked “convincing” when reported, and of course that it was published in Science. It goes without saying that the opinions of the real experts can safely be ignored since those will only be vented in specialist journals or in informal forums like Language Log. Science will apparently never open its pages to the airing of expert views that go against their program.

And thus science (?) advances (?).

The above is a guest post by Richard Sproat.

(myl) Since the comments were starting to devolve into arguments about irrelevant issues such as the Harappan system of weights, I've turned comments off. If you have something more to add to this discussion, feel free to send it to me in email.

G said,

May 25, 2013 @ 2:26 pm

It might not be for the advancement of science, but at least it's for the advancement of Science.

Richard Sproat said,

May 25, 2013 @ 3:13 pm

Yes, that is surely true.

Piotr Gąsiorowski said,

May 25, 2013 @ 3:18 pm

If the trend continues, the old joke about the Soviet-era Russian newspapers Pravda 'The Truth' and Izvestya 'The News' ("In The Truth there's no news; in The News there's no truth") will soon be applicable to Science and Nature.

[(myl) I continue, perhaps naively, to trust that the standards of high-impact journals for articles in biomedical areas are more, well, scientific. I cling to this faith in the face of some apparent contrary evidence, e.g. this and this.]

the other Mark P said,

May 25, 2013 @ 4:02 pm

Piotr, there's no need to follow the trend – it's already true that the "high impact" non-specialised journals are already more or less useless. Scientific American and New Scientist went down that path long ago.

The stuff they publish is not just wrong, but frequently risibly so. And to a non-specialist, it's impossible to tell which is which.

However since the publishers and the published continue to profit from the current situation, there is little chance their will be any

the other Mark P said,

May 25, 2013 @ 4:03 pm

any change.

D.O. said,

May 25, 2013 @ 4:13 pm

In most journalistic genres bad things (floods, scandals, crises) are considered more newsworthy than good things. Apparently it is not so in science. The discoveries are newsworthy and (a little scandal) that the latest discovery is a flop is not a big deal.

Piotr Gąsiorowski said,

May 25, 2013 @ 4:13 pm

(myl) I continue, perhaps naively, to trust that the standards of high-impact journals for articles in biomedical areas are more, well, scientific.

I have little such hope left; see (in addition to your examples) the unprecedented mass-publication, last September, of the ENCODE project results (30+ papers published simultaneously in several journals of the Nature Publishing Group), followed by a massive and carefully orchestrated media festival. The technical papers themselves were good science, but the accompanying comments and interpretations (such as this), press releases, interviews etc. were full of wildly inflated, sensational claims. As reported in Wikipedia,

The most striking finding was that the fraction of human DNA that is biologically active is considerably higher than even the most optimistic previous estimates. In an overview paper, the ENCODE Consortium reported that its members were able to assign biochemical functions to over 80% of the genome.

The 80% figure is based on using terms such as "biologically active" and "biochemical function" only in a strictly Pickwickian sense. The hype was susequently debunked by competent biochemists, but rarely in top-impact journals, which are naturally reluctant to undo their own PR efforts.

Richard Sproat said,

May 25, 2013 @ 4:16 pm

Unfortunately though, I assume (though I don't know this for sure) that having a publication in Science still counts a lot for tenure and promotion at lots of universities, even in the fields where the publications are often so, as Mark P so aptly puts it, risibly wrong.

This is presumably bolstered by the fact that it is, as this case shows, hard to get published in Science. The fact that it's hard to get in for all the wrong reasons is probably not something that T&P committees think much about.

Of course if one could change that …

Science won't change, because they have a great business model. What needs to change is the perception that what they publish is in fact good science.

Richard Sproat said,

May 25, 2013 @ 4:24 pm

@D.O.

Well unless things go seriously wrong — as cases like Hendrik Schön, Marc Hauser and Diederik Stapel — in which case it becomes exciting.

But yes, pointing out that something that people presumably enjoyed reading about was in fact arrant nonsense, is not in and of itself "newsworthy".

As a side note, interesting though that several of the cases that have gone seriously wrong (Schön, Stapel) in recent years have involved papers published in Science. I can only imagine the editors drooling over the beautiful looking (fraudulent) plots in those papers, much as I guess they must have done in the case of Rao et al's paper.

Piotr Gąsiorowski said,

May 25, 2013 @ 4:38 pm

This looks like another little scandal brewing.

Piotr Gąsiorowski said,

May 25, 2013 @ 4:46 pm

As a side note, interesting though that several of the cases that have gone seriously wrong …. have involved papers published in Science.

The "arsenic bacteria" fiasco is another example.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/GFAJ-1

Liberty said,

May 25, 2013 @ 6:45 pm

I was pleased to see that the LSA has endorsed a declaration to promote qualitative assessment of research (see here: http://www.linguisticsociety.org/news/2013/05/20/lsa-endorses-san-francisco-declaration-research-assessment and here: http://am.ascb.org/dora/). The focus in some prominent scientific journals on publishing studies which make huge claims has resulted in a lot of studies being published which are later discredited, at least in linguistics. This declaration is a small step in the right direction.

Jason said,

May 25, 2013 @ 11:40 pm

Reminds me of the high ideals of the "Journal of negative results in ecology and evolutionary biology." Perhaps every field needs its "anti-journal."

DCA said,

May 26, 2013 @ 12:10 am

Let me assure you, as someone who works in the natural sciences, that hiring and tenure committees continue to put great weight on publications in Science and Nature over publications anywhere else. And yes, I think the basic reasoning is "this club is exclusive so it must have only the best people", although a better way to think about it is "why are we outsourcing our personnel decisions to editors at two journals?"

Shivraj Singh said,

May 26, 2013 @ 12:51 am

Dear Richard,

I feel Science made the correct call. Let me explain my reasons:

a) If you did a statistical analysis of Indus valley civilization weights you will find that they are more precise compared to weights of other civilizations of their era. (Hemmy, A.S., 1938, System of Weights)

b) Indus valley civilization was spread over a much larger area compared to any other civilization of its era.

c) Finally I quote Karl M Petruso (Professor & Dean-Honors College, Professor-Anthropology UT Arlington):

"…metrological analysis of the available data has demonstrated that the Indus sites possessed a unique and elegant system of weight mensuration, which, by all indication, was regulated with great precision over an immense geographical area".

(Early Weights and Weighing in Egypt and the Indus Valley Karl M. Petruso M Bulletin (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) Vol. 79, (1981), pp. 44-51)

Question to ask oneself is : A civilization which has the highest mathematical precision in its weights and measures can it be illiterate?

Regards,

Shivraj

PS: For an analysis of Indus weights you can read this paper:

Shivraj Singh said,

May 26, 2013 @ 12:54 am

The link to paper is: http://www.tifr.res.in/~archaeo/papers/Harappan%20Civilisation/Harappan%20Weights.pdf (where it says %20 it is a space).

maidhc said,

May 26, 2013 @ 1:35 am

The Inca built a large technologically sophisticated civilization without having a writing system.

someone said,

May 26, 2013 @ 1:42 am

I see some irony in how application of science (e.g. techniques to maximize revenue) leads to destroying the reputation of science (science fraud, publisher's bias,…).

By blindly trusting an oversimplified 1-dimensional model of "utility" (i.e. "revenue"), science publishers appear to slowly make themselves less and less relevant, and unfortunately, in the course also negatively influence the public opinion about what science really is. It's a trend I also notice in other companies – all appear to be busy with cost-down projects, long after the most evident costs have been cut (read: companies start designing and selling inferior quality for higher prices).

Maybe publishing in the applied science community will need a revolution coming from the scientists themselves. For starters, a publication could consist of a repository including not only a paper, but also all data and software used in the research. The data should be in a readable (or at least fully documented) format and the software should be open for verification as well.

BTW: Any results of statistical analysis with your improved metric on the Voynich manuscript? :)

Shivraj Singh said,

May 26, 2013 @ 2:23 am

@maidhc : Gary Urton at Harvard disagrees with your assertion. Second the true extant of the destruction caused by Spanish in the Inca land will never be known fully.

Piotr Gąsiorowski said,

May 26, 2013 @ 4:06 am

Question to ask oneself is : A civilization which has the highest mathematical precision in its weights and measures can it be illiterate?

Of course it can. Why not? Regulating your system of weights and measures is perfectly possible without a writing system. And if several civilisations have seperately developed standards, one of the must be the most precise simply because they aren't identical.

Arguments from personal incredulity ("Can you imagine/believe…?") carry no weight.

peter said,

May 26, 2013 @ 5:35 am

Shivraj Singh said (May 26, 2013 @ 12:51 am)

"Question to ask oneself is : A civilization which has the highest mathematical precision in its weights and measures can it be illiterate?"

There's a post-Enlightenment tendency to believe that human thinking must necessarily involve language. But of course there are other forms of cognition – mathematical, visual, spatial, musical, for example. Given that individual humans can think non-linguistically, I see no reason to believe that human societies – even technologically advanced human societies – need to read and write text to function.

Mark Liberman said,

May 26, 2013 @ 5:53 am

I'm glad to see that Science is willing to publish non-replications, at least in some cases, specifically four "technical comments" in the current issue (here, here, here, here) documenting four separate failures to replicate a "highly publicized study" published last year in Science, claiming astonishing success for bexarotene in clearing amyloid plaque in mice with an analogue to Alzheimer's (“ApoE-Directed Therapeutics Rapidly Clear β-Amyloid and Reverse Deficits in AD Mouse Models”).

The cynical view, I suppose, is that a large fraction of the magazine's income comes from advertisements for biomedical instruments, supplies and services, so that a reputation for publishing splashy but unreliable papers, and then refusing to publish criticisms of them, would cut into the readership that these advertisers count on.]

Victor Mair said,

May 26, 2013 @ 6:18 am

@peter

"There's a post-Enlightenment tendency to believe that human thinking must necessarily involve language."

And especially written language. Cultures can achieve very high degrees of civilization without written language.

Richard Sproat said,

May 26, 2013 @ 6:54 am

@Shivraj

I'm sorry but I am not seeing the connection with what I wrote about and the issue of Indus weights, with which I am familiar, but which are totally separate from this issue.

And in any case, if you read my post, you'll see that the issue is not that the paper was rejected, but that it was rejected without peer review by the editors, who felt it was of no general interest.

So your comment as far as I can see entirely misses the point on at least two separate dimensions.

Richard Sproat said,

May 26, 2013 @ 6:56 am

@Shivraj (again)

I should add that I don't think the editors were basing their decisions on any prejudices about whether civilizations with supposedly sophisticated weight systems could or could not be literate.

In any case you are entirely missing the point.

Richard Sproat said,

May 26, 2013 @ 6:59 am

@Piotr Gąsiorowski

On Shivraj's post: right, of course. And in any case the claims of an amazingly sophisticated weight system in the Indus Valley in the 3rd millenium are nonsense. They had a weight system for sure (d'oh) and they certainly aimed for standards. But no 3rd millenium BCE civlization had a weight system that was anything other than crude by even recent premodern standards.

But that's a debate for another forum.

Richard Sproat said,

May 26, 2013 @ 7:07 am

@Victor

"And especially written language. Cultures can achieve very high degrees of civilization without written language."

Indeed. Odd how obvious examples of this do not spring to the mind of the many people who have expressed the view, often indignantly, that the Indus Valley must have been literate because of their apparent high degree of civilization. Cases like the Inca (unless you believe quipu were writing, which few do) somehow seem to escape notice. Or a number of preliterate cultures of Central America.

Shivraj Singh said,

May 26, 2013 @ 7:25 am

@Piotr

"Of course it can. Why not? Regulating your system of weights and measures is perfectly possible without a writing system. And if several civilisations have seperately developed standards, one of the must be the most precise simply because they aren't identical."

No. Precision in manufacturing identical weights requires ability to do careful measurement. Accurate measurement requires the need to develop mathematics.

What you are saying is it is possible for a civilization to develop the language of math but not what they spoke.

Your logic is flawed. Unless ofcourse you can back up your hypothesis with some testable data.

@Piotr

"Arguments from personal incredulity ("Can you imagine/believe…?") carry no weight."

Show me the data which supports your assertion!

Shivraj Singh said,

May 26, 2013 @ 7:28 am

@peter

"There's a post-Enlightenment tendency to believe that human thinking must necessarily involve language. But of course there are other forms of cognition – mathematical, visual, spatial, musical, for example. Given that individual humans can think non-linguistically, I see no reason to believe that human societies – even technologically advanced human societies – need to read and write text to function."

I am sure we are all entitled to our beliefs, after all it does seem to be a free world, but would you have any examples of a culture who have mathematics but not a written language?

Shivraj Singh said,

May 26, 2013 @ 7:31 am

@Richard Sproat

"I'm sorry but I am not seeing the connection with what I wrote about and the issue of Indus weights, with which I am familiar, but which are totally separate from this issue."

No! They are thoroughly linked. Ability to do Maths and language are intricately related. You are arguing for Indus civilization had no language (Since Rao is wrong!) and I am saying your thesis is flawed and hence Science is correct in its analysis of your paper, with or without peer review.

Shivraj Singh said,

May 26, 2013 @ 7:35 am

@Richard Sproat

"And in any case the claims of an amazingly sophisticated weight system in the Indus Valley in the 3rd millenium are nonsense. They had a weight system for sure (d'oh) and they certainly aimed for standards. But no 3rd millenium BCE civlization had a weight system that was anything other than crude by even recent premodern standards."

Apples and Oranges. You have to compare weights of Egyptian and other contemporaneous civilizations of Harappa to see which had the most accurate weights. Hemmy did the analysis in his 1938 paper and concluded that Indus weights were the most accurate.

Shivraj Singh said,

May 26, 2013 @ 7:39 am

@Richard Sproat

"Indeed. Odd how obvious examples of this do not spring to the mind of the many people who have expressed the view, often indignantly, that the Indus Valley must have been literate because of their apparent high degree of civilization. Cases like the Inca (unless you believe quipu were writing, which few do) somehow seem to escape notice. Or a number of preliterate cultures of Central America."

Have you had a chance to look at Gary Urton's work on Incas at Harvard? I would love to hear why Gary is wrong and you are right on the ability of Incas to write.

Richard Sproat said,

May 26, 2013 @ 7:54 am

@Shivraj

I've seen that work. It's not convincing to me yet, but maybe it will be. But in any case if you don't like that example I can give you other examples of illiterate civilizations.

In any case you seem not to be able to stop missing the point: this isn't about whether or not the Harappans were literate. It's about whether solid statistical analysis can or cannot bear on that question. And more particular to this thread, whether journals like Science have a responsibility to publish solid work, whether or not it appeals to your own personal taste.

And alternatively whether they should be publishing flaky work: I don't recall you complaining about Rao et al's paper, despite the obvious problems, presumably because it went in the direction you want.

In any case I still believe as I always have: that the issue of the Harappans' literacy must be addressed by solid archaeological evidence, viz., a long text, or a verifiable decipherment. Statistical analysis can provide nothing more than hints. I think I have been consistent on this point.

Richard Sproat said,

May 26, 2013 @ 7:56 am

@Shivraj

"No! They are thoroughly linked. Ability to do Maths and language are intricately related. You are arguing for Indus civilization had no language (Since Rao is wrong!) and I am saying your thesis is flawed and hence Science is correct in its analysis of your paper, with or without peer review."

Ok Mr Shivraj: if you are not able to distinguish between writing and language, we have nothing further to discuss. I suggest you may want to go and read a linguistics textbook sometime, which may enlighten you on why those two issues are distinct.

bks said,

May 26, 2013 @ 8:22 am

When are scientists going to stop using red and green on graphs to differentiate data?

–bks

Gene Buckley said,

May 26, 2013 @ 8:56 am

Richard Sproat writes that "this isn't about whether or not the Harappans were literate. It's about whether solid statistical analysis can or cannot bear on that question. And more particular to this thread, whether journals like Science have a responsibility to publish solid work, whether or not it appeals to your own personal taste."

Well put. Even if one believes that a complex civilization must possess linguistic writing, it is entirely different to claim proof that a particular graphical system represents language (and for editors to publish an analysis as proof).

For an analogy relevant to the editors of Science: One might be firmly convinced that there are intelligent beings on other planets, but it's a different matter to publish transcripts of conversations with them.

peter said,

May 26, 2013 @ 10:08 am

Shivraj Singh said (May 26, 2013 @ 7:28 am):

"but would you have any examples of a culture who have mathematics but not a written language?"

Yes, the culture of the mathematicians who study geometry. Here is the late Fields Medallist William Thurston, talking of the geometry of 3-manifolds:

"Mathematical knowledge and understanding were embedded in the minds and in the social fabric of the community of people thinking about a particular topic. This knowledge was supported by written documents, but the written documents were not really primary.

I think this pattern varies quite a bit from field to field. I was interested in geometric areas of mathematics, where it is often pretty hard to have a document that reflects well the way people actually think."

See: William Thurston [1994]: On proof and progress in mathematics. American Mathematical Society, 30 (2): 161-177.

dg said,

May 26, 2013 @ 10:43 am

I'm truly stunned by Shivraj's comments here for every reason given by Richard Sproat. They suggest another, important cultural trend that's not been remarked upon: the continuing incursion of non-linguists into the study of language, in part predicated on a general rejection of the expertise of linguists themselves. We've seen it several times now in major science journals, when physicists and computer scientists and biologists produce results that most linguists immediately see as based on obviously flawed assumptions that contradict basic linguistic research. In almost every case, this work "proves" something about the basic relatedness of many disparate language families, the co-evolution development of languages with one biological development or another, the location of ur-languages, and so on. From my reading, Science and Nature rarely publish work by non-physicists on physics, non-chemists on chemistry, etc., but for linguistics they make an exception, and then routinely refuse to publish thoughtful refutations of the non-specialist work no matter how well-crafted or well-informed. There is something truly rotten here and I hope the LSA or another similar body can intervene in some way to "encourage" such major publications to treat this field the way they treat most others.

Rajesh Rao said,

May 26, 2013 @ 10:55 am

Richard:

I applaud the effort to collect a larger corpora of non-linguistic systems. I however disagree with your interpretation of the results and your continued dismissal of ours.

First, as we discussed in detail in our Computational Linguistics paper, the entropic results must be viewed in the context of an inductive framework in conjunction with other known properties of the Indus script (rather than in a purely deductive sense as you do here and have done previously). We have listed several such statistical properties in our N-grams paper. In the inductive framework, we can only assign a probability that the Indus script is linguistic, but cannot say with definiteness that it is one or the other. Our current estimate is that taking ALL the statistical signatures into account, there appears to be more evidence in favour of the Indus script being linguistic, than not.

Second, your block entropy plot in fact reinforces our point that the vast majority of linguistic systems tend to cluster and exhibit similar entropic scaling properties: in your plot, all of your linguistic systems (except one) exhibit this property (Sumerian seems to be fall somewhat below the others in your plot but not in ours).

Finally, though the following point is not relevant to the inductive argument, concerns can be raised about the only two "non-linguistic" systems that seem to fall in the linguistic range in your plot: Pictish and Kudurru. It is not clear why you classify Pictish as non-linguistic given that this is still an open question and this is what Rob Lee et al.'s paper was attempting to shed light on. As for Kudurru, as you mentioned in your 2010 Comp Linguistics paper, a large enough data set of kudurru sequences does not exist to compute meaningful estimates of quantities such as block entropy, and one should therefore take the kudurru plot with a grain (or more) of salt.

I would therefore reserve judgment rather than jump to the conclusion that the Indus script (or indeed Pictish) is non-linguistic given your results.

Rodger C said,

May 26, 2013 @ 11:57 am

On another note, I'm rather taken aback by your reference to the Harappans as "a 4500-year old civilization that most people outside of South Asia have never heard of." Surely every student of history knows about the Harappans and their notation-system-or-whatever?

Howard Oakley said,

May 26, 2013 @ 12:07 pm

I am surprised that no-one has raised what I see is a more fundamental issue here, that of (research or publishing) governance.

Irrespective of the arguments aired here, Richard Sproat's submissions tackled what he perceived to be shortcomings in work that had been published in Science.

For the editors to arbitrarily refuse to submit his work to peer review is to deny any possible criticism of that published work. Thus they have biased what they publish, which is a fundamental failure to follow the very title of the journal – Science.

Without open debate, there is no science.

Howard.

Ronojoy Adhikari said,

May 26, 2013 @ 12:10 pm

Richard :

I can understand your incredulity at your paper being rejected by Science without peer review, but, for many high-impact journals, including Science, most journals of the Nature group, PNAS, and Physical Review Letters, it is an editor that makes a first call on the suitability of the paper for peer review. The last journal, for instance, rejects about a third of submissions without peer-review

http://prl.aps.org/edannounce/PRLv95i7.html

My commiserations that your submission met this fate, but rest assured that many other authors (including myself) have shared in it.

Ronojoy Adhikari said,

May 26, 2013 @ 12:19 pm

Howard :

You write : "For the editors to arbitrarily refuse to submit his work to peer review is to deny any possible criticism of that published work."

If you read this thread fully, you will see that the editors of Science did offer Sproat et al a chance to comment on our work ("We invite you to resubmit your comments as a Technical Comment.") but as Richard says :

"We never did follow up on the invitation to submit a Technical Comment .."

Thus, Sproat et al actually let up a chance to have their comment peer-reviewed and possibly published as a technical comment in Science, under the assumption that

".. we know very well what would have happened if we had."

From where I stand, I can see no evidence of bias in the editors of Science in this particular sequence of events.

Richard Sproat said,

May 26, 2013 @ 12:43 pm

@Rajesh Rao

Hi Rajesh

I guess you'll have to read the paper and see. You can disagree, and I assume will. And you should assume that I understand very well what your interpretation of your results was, though that interpretation only came to light well after your paper was published. I think I have shown convincingly that on whatever interpretation you choose, the evidence does not support your conclusions. It seems that most linguists and computational linguists understand my point and agree with me, but maybe we're all ignorant of some deeper insights that you see and we do not.

Certainly the middle area on the entropy curves is where language clusters. It's also where lots of other symbol systems fall, which is what I show. So it does not tell us much. Oddly, you seem to reject a measure based on repetition rate that on the face of it seems to provide a much clearer kind of evidence.

It's certainly true that if you had submitted plots that looked like the plots in my paper as opposed to the plots that you did submit that were based at least in part on artificial data that in turn were based on an unequivocal misinterpretation of the way the Vinca and kudurru systems work: well in that case your paper would not have been published.

@Howard Oakley

Completely correct: that is the fundamental point here. Whether my analyses continue to be upheld with the continuing collection and analysis of more data remains to be seen, I have called into serious question the results of published work. That is what scientific debate is all about, and there should be an outlet for that in self-styled "prestige" journals like Science.

Richard Sproat said,

May 26, 2013 @ 1:02 pm

@Ronojoy Adhikari

Yes, well I don't doubt they reject much of what they get. But if they reject out of hand without review based on nebulous criteria that do not stand up when you consider the stuff they do end up publishing in an area, then one must look askance at them and wonder whether they are serious about publishing good science.

As for whether we would have succeeded with a "technical note" back in 2009: I see no reason to assume that. They rejected a very short letter. They rejected out of hand a very detailed piece of work that is the theme of this thread. Why should one believe they'd have behaved differently on that other occasion? I'm pretty sure the email we got inviting that was a form letter, just as the one I got the other day apparently was.

Richard Sproat said,

May 26, 2013 @ 1:07 pm

@Rodger C

"On another note, I'm rather taken aback by your reference to the Harappans as "a 4500-year old civilization that most people outside of South Asia have never heard of." Surely every student of history knows about the Harappans and their notation-system-or-whatever?"

Do they? Many Westerners I have talked about this stuff with certainly didn't know much if anything.

There's also a question of what they know. For example if you look under "Indus Valley writing" here:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/schools/primaryhistory/indus_valley/art_and_writing/

you'll see an amazing piece of imaginative fabrication posing as real history.

Richard Sproat said,

May 26, 2013 @ 1:09 pm

@Gene Buckley

" Even if one believes that a complex civilization must possess linguistic writing, it is entirely different to claim proof that a particular graphical system represents language (and for editors to publish an analysis as proof)."

Yes indeed.

Richard Sproat said,

May 26, 2013 @ 1:15 pm

@dg said,

"I'm truly stunned by Shivraj's comments here for every reason given by Richard Sproat."

I am, unfortunately, not too surprised, especially given this topic. It touches a raw nerve for some people. Well that's too bad: one has to learn to be able to look at data dispassionately, and sometimes things don't appear the way one would like them to.

Richard Sproat said,

May 26, 2013 @ 1:17 pm

@bks

"When are scientists going to stop using red and green on graphs to differentiate data?"

Oops. Right. Sorry about that: I should — and will in future — remember that.

Kyle Gorman said,

May 26, 2013 @ 1:37 pm

@Richard: I cannot imagine any reason to reject your highly-relevant paper (recall, everyone, that they had previously published a paper using exactly the same method Richard has subject to careful critique!) except the one you outline.

What is to be done? Working linguists (and psycholinguists, perhaps to a lesser degree) are already quite aware that papers in Science and Nature are deeply suspect. Can you find a higher soapbox than Language Log? I do not believe there will be any change unless your message gets beyond a specialist audience.

Richard Sproat said,

May 26, 2013 @ 1:49 pm

@Kyle

Hi Kyle:

Nice to hear from you. I hope Oregon is treating you well.

Right, so I am thinking that the only thing one can do is to try to educate university administrations, especially P&T committees, that publication in Science is not the top-level Good Housekeeping seal of approval on one's work they seem to assume it is and — given what we have seen — can even mean quite the opposite.

As I suggested above Science is not going to change their ways, so it's probably useless to try to get them to take their responsibilities to publish good, well reviewed, work in language and related areas seriously.

But if the "customers" of their product start changing their views, then they can either choose to change how they operate, or else become irrelevant.

One of the comments that Rajesh Rao made some years ago went something like: how can people like Steve Farmer and I continue to trash their (Rao et al.'s) work even given that it has been published in such venues as Science or PNAS? If you replaced those two with Time and Newsweek the question would of course become ludicrous. But that's essentially what we are dealing with here, and that needs to be clarified so that a wider body of people understand it.

I don't know how to effect that change though, other than by proclaiming loudly at every opportunity one gets.

Shivraj Singh said,

May 26, 2013 @ 2:27 pm

@Richard

"I've seen that work. It's not convincing to me yet, but maybe it will be. But in any case if you don't like that example I can give you other examples of illiterate civilizations."

Please by all means do give examples. The constraints that need to be solved are:

a) The civilization needs to know math, well.

b) Unable to write what they speak.

@Richard

"In any case you seem not to be able to stop missing the point: this isn't about whether or not the Harappans were literate. It's about whether solid statistical analysis can or cannot bear on that question. And more particular to this thread, whether journals like Science have a responsibility to publish solid work, whether or not it appeals to your own personal taste."

Since you bring to bear "solid statistical analysis" why don't we start with a simpler, more tractable problem. In an earlier post there is a link to data on Harappan weights, which I am sure you have seen earlier. Can you please post an analysis of these Harappan weights?

Regarding missing the point I am surprised you fail to see the connection(deliberatley?) that Maths and writing go hand in hand. You cannot have a civilization with most precise weights of its times and yet be illiterate.

Is rejection in Science a case of sour grapes?

Shivraj Singh said,

May 26, 2013 @ 2:30 pm

@dg

"I'm truly stunned by Shivraj's comments here for every reason given by Richard Sproat. They suggest another, important cultural trend that's not been remarked upon: the continuing incursion of non-linguists into the study of language, in part predicated on a general rejection of the expertise of linguists themselves. "

Is this some kind of an "earth is flat and everybody should support it" argument?

Richard Sproat said,

May 26, 2013 @ 2:41 pm

@Shivraj

This is not a forum for discussing the thesis that the Indus civilization must have been literate because of a supposedly amazing weight system, which in turn supposes some amazing mathematical abilities. That thesis has been discussed at length elsewhere in any case.

Therefore I am not going to deal with this issue here: I will deal with your issues offline if you so choose.

Richard Sproat said,

May 26, 2013 @ 2:44 pm

@Shivraj

"Is rejection in Science a case of sour grapes?"

I would say it's a case of having an expectation that somebody is going to behave in a certain way, hoping that it isn't true, and then discovering that, counter to hope, they actually exceed expectations.

I'm seeing a bit of that on this thread too.

Ronojoy Adhikari said,

May 26, 2013 @ 3:00 pm

Richard :

Your grounds for "Why should one believe they'd have behaved differently" may make some sense in the light of this most recent (and second) dismissal from Science, but it is puzzling if you also held this opinion at the time the editors invited you to submit a technical note, admitting, candidly enough, that not being able to publish your response was "not necessarily a reflection of the quality of your letter but rather of our stringent space limitations." Or, were you already cynical about about their editorial policy at the first slight ? Why, then, send your paper to them again ?

The way I see it, "self-styled 'prestige' journals like Science" did provide you an outlet to question what they had published, but unlike the authors who wrote back on non-replications (see Mark's post) you thought this not worth your while! Cannot see, still, how Science is to be blamed for this!

Rahul Siddharthan said,

May 26, 2013 @ 3:05 pm

Without getting into the merits of Sproat's current post, which Rajesh Rao and Ronojoy Adhikari are competent to handle, I have to wonder — why publish here and not in a scholarly journal? So Science rejected it — why not publish elsewhere? Did MYL attempt to peer-review Sproat's work before publishing it here?

But this seems to be standard procedure for Sproat and his colleagues. The paper that started it all, "The Collapse of the Indus script thesis: The myth of a literate Harappan civilization", by Farmer, Sproat and Witzel, appeared in an electronic journal edited by Witzel, and I wonder whether it was reviewed at all. Further discussion appeared in — where else — Science magazine.. Readers may decide, of the titles and abstracts of Farmer-Sproat-Witzel and of Rao et al, which is adequately circumspect and evidence-based and which is declamatory and polemical. Reading of the Farmer-Sproat-Witzel paper reveals that it is based on essentially no new evidence, only a series of arguments by the authors that are, to say the least, arguable. If Sproat wants to accuse authors of publishing without adequate evidence and of using their personal prestige to appear in Science magazine, he should look closer to home.

Finally, I did have a concern about the original Rao et al paper on why they took only two rather contrived examples of non-language sequences: DNA and Fortran. It is good to know that Sproat has spent his time compiling corpuses of various texts, but why not include other non-language sequences — such as music, road signs, bird song, mathematical equations (in TeX or MathML form), or any number of other examples that exist in abundance and whose non-linguistic nature is not in dispute? Why limit non-language examples to Pictish (disputed) and Kudurru (inadequate corpus)?

Richard Sproat said,

May 26, 2013 @ 3:07 pm

@Ronojoy Adhikari

Why didn't we? I think it was a combination of many reasons, which given it was 4 years ago, I don't well remember. I'm sure part of it was that since this was (and is) just a part-time occupation for me, I felt I had spent as much time at the time on it as I could.

Except that I didn't seem to be able to avoid being sucked back into it.

Anyway, I'm sure you'll believe what you want :)

Sili said,

May 26, 2013 @ 3:23 pm

Datapoint of one, but I certainly wouldn't have known of the Indus Valley Script, if I hadn't been an LL reader.

Sili said,

May 26, 2013 @ 3:27 pm

Presumably collecting and analysing completely new corpusses if hard and expensive work. I would assume that Sproat has collated as much data as his grant allowed him.

[(myl) Music is a good idea, and scores are now widely available in digital form, though you would have to decide how to treat it — pitch or pitch-class sequences in melodies? or harmony sequences? With or without timing information? I'm not sure what is meant by "road signs" — if it means the sequence of sign types along particular stretches of road, that would be interesting, but would require some effort to collect. Bird song is also a good idea, but not easily available in symbolic form in any published collections that I'm aware of, so some effort would be needed.]

Phil Jennings said,

May 26, 2013 @ 3:33 pm

I can imagine an obsessive viking recording the results of casting runes during a consultation with the gods. I've been told that after the fifth century ce, cuneiform was used for divination in Luristan, after it no longer served in Mesopotamia for writing, and perhaps tablets can be found that demonstrate this use.

In these examples I conjecture that true scripts might be employed to record texts that fail the entropy test because those texts don't represent language. Scripts used to transcribe music (as cuneiform was used in Ugarit) would also fail the entropy test. Likewise scripts that record horoscopes. If all we have is a small collection of texts and we measure the lot entropically and judge the result in sum, we might come to an unfair conclusion.

On the other hand, this entropic method might distinguish real language texts in the Indus script from texts that serve other purposes. Perhaps these texts have been studied severally as well as together and none have passed muster. Is that the case?

I'd be curious to read about other non-linguistic uses of linguistic scripts, if anyone has better examples that are relevant here. I speculate that true writing came early if not first, and that departures like heraldic blazons and records of chess games followed after.

Ronojoy Adhikari said,

May 26, 2013 @ 3:47 pm

Any takers for bottle-nose dolphin vocalizations ?

http://cocosci.berkeley.edu/josh/papers/JoshAbbott-Thesis.pdf

Know this because they cited us :)

Richard Sproat said,

May 26, 2013 @ 4:15 pm

@Rahul Siddhartha

Nonsense Rahul. Who said I am not going to publish it. I am certainly going to try. You are jumping to unwarranted conclusions.

As for your last point:

"but why not include other non-language sequences — such as music, road signs, bird song, mathematical equations (in TeX or MathML form), or any number of other examples that exist in abundance and whose non-linguistic nature is not in dispute? Why limit non-language examples to Pictish (disputed) and Kudurru (inadequate corpus)?"

Weather icon sequences for example? Or components of Asian emoticons? I also have mathematical equations, and didn't report them here coz I'm not done with the corpus. But you can see them in my monograph posted on my home page. They behave just like the rest of these non-linguistic systems.

I think the basic problem is that nothing that anyone does is going to convince some of the posters on this thread.

Richard Sproat said,

May 26, 2013 @ 4:26 pm

@Phil Jennings

These are interesting points, though w.r.t. the point about distinguishing real language texts from other uses in the Indus whatever-it-was, then one problem (often forgotten in these discussions) is the extreme brevity of the texts, making it rather hard to draw robust conclusions of any kind. (And on the other hand making it all too easy for would-be decipherers to fit their pet theory to the inscriptions.)

But you're right: there certainly are non-linguistic uses of linguistic scripts: I think the Asian emoticon example I use in my paper is another good example.

As for your speculation at the end: I'm not sure I understand. Obviously blazon did come after writing since it uses written words to represent heralds. Which is not to say that the language of blazon is not completely artificial. But is the point that complex non-linguistic systems must postdate writing? Surely not, since writing seems to have evolved — to the extent we know how it evolved — from complex non-linguistic systems.

Brett said,

May 26, 2013 @ 5:02 pm

@Ronojoy Adhikari: This is growing well off topic, but I don't think the characterization of the editorial practices of Physical Review Letters (PRL) as similar to that of Science or Nature is fair. In fact, I think PRL does a pretty good job of striking the kind of balance that is required for a high-impact journal with a high rejection rate. I believe that the whole Physical Review family of journals provide an excellent example of how scholarly publishing can be done right (and inexpensively).

It may be that PRL rejects 20-25% of the submissions they receive. However, as a submitter, a regular referee, and somebody who chats occasionally with the journal editors, I am pretty confident that the bulk of what they reject is obviously unacceptable. There are two big reasons why a manuscript could be manifestly unsuitable. The first is that it doesn't fit the submission requirements for length, format, etc. These would be rejected out of hand at any journal, and the people responsible for such submissions may be overwhelmingly cranks. The second reason for an editor to reject something out of hand is if it's manifest nonsense. It's easier to do this in a journal like PRL, where all the editors have doctorates in physics, than a more general journal like Science. However, the editors seem to send papers out for review if there's any real question of their validity. I get plenty of stuff to referee that is, to me as an expert, clearly erroneous.

Once the papers are sent for review, the decisions about whether something is of sufficient interest for the journal are basically left in the hands of the referees. Only once in all my back-and-forth exchanges with the editors that I've had as an author has an editor raised additional questions about whether something was high enough profile. In that one instance, it was quite a legitimate question, and when I addressed it, the paper was published without any further problems. It's also noteworthy that PRL routinely (if not hugely frequently) publishes refutations of previous work, even work that was published in lower-tiered journals.

The journal restricts the number of acceptances by essentially requiring that all the referees agree about both correctness and sufficient interest for a paper. (The number of referees on published papers may be anywhere from one to four.) If most or all of the referees agree a paper is correct, but there isn't unanimous agreement about the importance, the other Physical Review journals will generally offer to publish the papers, possibly with some further modification but often without any additional changes.

Jonah said,

May 26, 2013 @ 5:19 pm

Just to confirm, the email from Gilbert Chin is indeed a form letter. I got the same one from him, word for word, a few weeks ago. While I wasn't expecting Science to publish my paper, I assumed that it would be because it wasn't interesting to people outside my specialty area (the paper shows that rhyme patterns in American English hip-hop lyrics display parallels to implicational universals in phonological typology; the hypothesis is that both domains reflect speakers' implicit knowledge of asymmetries in speech perception). I was shocked by the email that they actually did send (which is the same one from the post above); it's a lot more honest than I would have expected. They're essentially coming out and saying this: "We sent your paper for a skim to a bunch of people with no training in or knowledge of linguistics and asked them to compare it to previous papers we've published on language, none of which have any actual linguistic analysis in them and most of which fail to meet basic standards of scientific competence. These skimmers agreed that your paper was more difficult to understand, so we decided not to proceed with actual peer review. Why don't you go publish it somewhere where people will understand it?" The fact that they sent the same email to Richard Sproat, who provided clear evidence that a paper *they'd already published* is false, is something close to Orwellian.

I wonder if it's about time for the LSA to pass a resolution expressing no confidence in Science's reviewing practices and publications on language. I think the evidence of gross negligence is pretty strong at this point: the Atkinson fiasco(es), the fact that they apparently ignored the lone review from an actual linguist in that case, their stated refusal to even review linguistics papers that can't be easily understood by non-linguists (do they apply this criterion to biochemistry or particle physics?), and their hilarious assertion that the Indus inscriptions being linguistic is of interest to their readership but conclusive evidence that their published claim that Indus inscriptions are linguistic is false is not of interest. Not that an LSA resolution would do much, but it could at least get picked up in the academic news, where administration types might notice it and Science might be embarrassed.

David Pesetsky said,

May 26, 2013 @ 7:52 pm

There is also a Linguistics and Language Science section in the AAAS (sadly also known as "Section Z", no kidding), with an eminent and diverse collection of current officers:

http://www.aaas.org/aboutaaas/organization/sections/ling.shtml

Though Science is, I believe, run at arms length from AAAS, there is probably also role for Section Z to play in urging a more professional publication policy for the Association's flagship journal, when it comes to our field.

Is the Voynich Manuscript structured like written language? « Glossographia said,

June 24, 2013 @ 7:31 am

[…] and conceptual approaches, some of which has been covered in extraordinary detail at the Language Log. There's a much longer discussion to be had there, but suffice it to say that most […]