Jumbled Chinese

« previous post | next post »

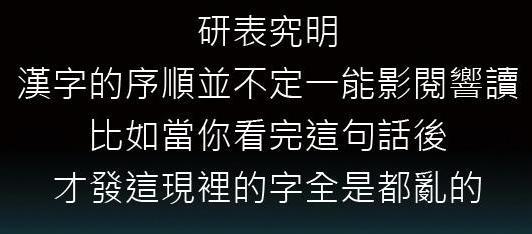

I knew it wouldn't be long before someone came up with a Chinese equivalent to alphabetical typoglycemia:

The text reads:

Yán biǎo jiū míng

Hànzì de xù shùn bìng bù dìng yī néng yǐng yuè xiǎng dú.

Bǐrú dāng nǐ kàn wán zhè jù huà hòu

cái fā zhè xiàn lǐ de zì quán shì dōu luàn de.

研表究明

漢字的序順並不定一能影閱響讀

比如當你看完這句話後

才發這現裡的字全是都亂的

Without rearranging, this makes little sense (except the third line, which is in the correct order).

Here are all four lines in the correct order:

Yánjiū biǎomíng

Hànzì de shùnxù bìng bù yīdìng néng yǐngxiǎng yuèdú.

Bǐrú dāng nǐ kàn wán zhè jù huà hòu

cái fāxiàn zhèlǐ de zì quándōu shì luàn de.

研究表明

漢字的順序並不一定能影響閱讀

比如當你看完這句話後

才發現這裡的字全都是亂的

Studies have shown that the order of Chinese characters does not necessarily affect reading. For example, after you've read this sentence, you'll realize that the characters are all completely disordered.

The is indeed curious, but I wouldn't say that "the characters are all completely disordered", since in this text of 40 characters, there are only 6 instances where the order of the characters has been changed. Moreover, the only type of change employed is simple inversion of characters that are parts of well-established disyllabic terms. This is really quite tame in comparison with the more extreme kinds of typoglycemia that may be applied to writing in English.

I wonder what would happen if we started moving strokes around within characters, which might be a better analogy to typoglycemia in English.

[A tip of the hat to Yuanfei Wang for sending me the text; thanks to Gianni Wan and Fangyi Cheng]

Gene Buckley said,

April 13, 2013 @ 10:02 am

Another analogy to moving letters around in an alphabetic word is to swap the radicals or phonetics among characters in the same word.

Gianni said,

April 13, 2013 @ 10:28 am

Take the second line as an example:

I rearrange it into this:

讀漢序字響的能定影順並不一閱

This greatly hinders my reading!

Thus the key is that our brain recognize Chinese by WORDS and NOT CHARACTERS, and of course NOT SENTENCE.

Compare:

漢字的序順並不定一能影閱響讀

Only 序順 and 閱響 are switched. Three words are affected but the syntax remains the same.

Nocti said,

April 13, 2013 @ 8:00 pm

Tried it with Japanese, changing all the characters I could to more or less visually similar ones:

嘆子の陪目や反各の蜀占なとを恋えれは艮いておろう。

The original sentence was this:

漢字の部首や仮名の濁点などを変えれば良いであろう。

kanji no bushu ya kana no dakuten nado wo kaereba yoi dearou

I can't be sure that I perceive this as a native speaker would, but for me there is a definite distinction between those characters where the 'overall shape' changes and those where it doesn't. With 蜀占, for example, the first character is so similar to the original that I wouldn't notice the change (helped by both 濁 and 蜀 being very uncommon), but the second is unreadable (not helped by 点 and 占 being very common).

The dakuten (the ゛above kana indicating voicing) are also very important, and for me it's hard to make sense of the sentence when they're wrong. I'd be interested to see if that's the same for a native Japanese speaker.

JS said,

April 13, 2013 @ 8:09 pm

The best proof of this effect must be that Prof. Mair counts only six instances of reversal (there are seven… I think), and Gianni reads over the reversal of 一定 in the second sentence…

As for Prof. Buckley's suggestion, I find myself doubting the effect would persist as the smallest graphical units mapping to units of language–the characters–would be disturbed…. but someone should whip something up.

Jason Chen said,

April 13, 2013 @ 11:59 pm

here's an instance of "moving strokes around within characters" where the two-character phrase "脑残"(lit. brain-damaged) is moulded into a single unit

http://e.hiphotos.baidu.com/baike/pic/item/3b87e950352ac65c44735f25fbf2b21193138a75.jpg

JQ said,

April 14, 2013 @ 9:04 am

When reading English (and French, Spanish, etc.) I always hear the sound of the word inside my head, as there isn't really any way to avoid it because of the alphabetic nature of the language.

With jumbled English I find that I still hear the sound of the word (correctly spelled!) inside my head despite this not being how it appears on the page.

When reading Chinese, I don't always sound out the words in my head, since the shape of the characters allows my brain to process the meaning without needing to work out how it would be pronounced.

When I attempted to skim read the passage, it made sense as I was not trying to "hear" what it said, only to gather a gist of the meaning. When I tried reading it a bit more slowly and trying to hear the sound of each character in my head, it stopped making sense without further processing.

Interestingly, when reading Cantonese (which is more native to me), I find I need to sound out all the words before I can understand what the writing says, since Cantonese is not usually written, or is written in a translated fashion that does not reflect what is actually being said (à la HK TV subtitles). Because of this, when reading newspapers aimed at Cantonese speakers (HK or overseas titles) I still find it easier to read characters serving a grammatical function in Mandarin, and vocabulary in Cantonese.

So from the example passage, the slowest part for me to read was "才發這現裡" since I started off in Mandarin mode for 才, then shifted to Cantonese mode for 發 assuming that 現 would come next, but instead encountered 這, which needed to be translated to 呢 in Cantonese or shift back to Mandarin mode…

Matt said,

April 14, 2013 @ 6:56 pm

I wonder what would happen if we started moving strokes around within characters, which might be a better analogy to typoglycemia in English.

We'd recapitulate the historical development of hanzi (and hanzi-derived) orthography. (Rimshot.)

I can't be sure that I perceive this as a native speaker would, but for me there is a definite distinction between those characters where the 'overall shape' changes and those where it doesn't. With 蜀占, for example, the first character is so similar to the original that I wouldn't notice the change (helped by both 濁 and 蜀 being very uncommon), but the second is unreadable (not helped by 点 and 占 being very common).

I'm not a native speaker either, but I had a slightly different experience. 蜀占 was completely readable for me, and while I agree that my brain probably just parsed 蜀 as a damaged 濁 (because I never encounter 蜀, and didn't "know" it until I just looked it up; it's simply not a possibility in my mind), I think that I parsed 占 as /ten/ because it retains the essential phonetic information — that is, I associate the shape with the pronunciation /ten/ due to its appearance in the very common characters 点 and 店. (On the other hand, 陪目 was completely opaque.)

Priming probably also has an effect. I bet a significant number of people would interpret 蜀占 in isolation as a mangled 独占.

richardelguru said,

April 15, 2013 @ 6:08 am

As an aside, I first thought that typoglycemia was an addiction to using the old Shatter font.

Matt McIrvin said,

April 15, 2013 @ 11:08 pm

This reminds me more of verlan.

Dan Hemmens said,

April 16, 2013 @ 3:15 pm

I could be wrong, but I've always understood that a *lot* of the more classic typloglycemia examples are quite similar in this sense – certainly I remember the classic internet meme (the one on which this text appears to be based) relying mostly on a relatively small number of substitutions of close pairs of letters. They tend to use short words, so the restriction to leave "the first and last letter the same" leaves two and three letter words completely unchanged, and four letter words unchanged except for a direct substitution.