-ant, -ent, whatever

« previous post | next post »

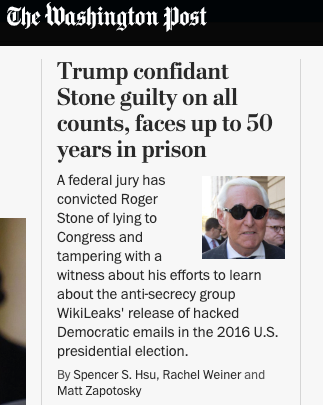

This Washington Post item confused me for a few seconds:

I first interpreted the headline as "Donald Trump is confident that Roger Stone is guilty on all counts, and" (whoops) "he (=Trump) faces up to 50 years in prison"?

I was sent down this particular garden path by the recent flurry of news stories about the president throwing various supporters under the metaphorical bus. But the whole -ant v. -ent mess didn't help.

Like many English speakers, I have trouble remembering whether to use 'a' or 'e' in words ending in -ant or -ent, like dependant and independent. Since both endings are unstressed, the pronunciation of their vowels in English is the same. And in some cases, the spelling depends on whether the Latin source was a first conjugation (a-stem) verb, like portans → important, or a verb of the second, third, or fourth conjugations, like pendens → independent. But as the OED explains,

In Old French, the participial forms descending from classical Latin -ant- , -āns as well as the more common -ent- , -ēns were generally levelled under -ant , which became the sole ending of the present participle.

So English words borrowed from (Old) French may have -ant regardless of their Latin origin, unless spelling mavens corrected the vowel later, whereas words borrowed from later French, or directly from Latin, follow the Latin model. The OED again:

The conflict between English and French analogies occasions frequent inconsistency and uncertainty in the present spelling of words with this suffix; cf. e.g. assistant, persistent; attendant, superintendent; dependant, -ent, independent.

English confident gets its 'e' from Latin confido, confidere "to trust, confide, rely upon, believe, be assured". But in French, the word confidant.e was taken up, from the same Latin source, early enough to undergo the levelling of -ent to -ant. And confidant, defined by Johnson as "A person trusted with private affairs, commonly with affairs of love", was borrowed into English from French relatively late, as the OED explains:

This appears, with its feminine confidante, after 1700, when confident (with stress on the first syllable) had already been in use for nearly a century in a kindred sense.

Of course I know the difference between confident and confidant — and in this case, there are two meanings and two pronunciations as well. But in most cases, the 'e' vs. 'a' choice makes no difference in either meaning or pronunciation, and it's just one more arbitrary thing to learn about English orthography. So it's too bad that neither Noah Webster nor any later spelling reformers have dared to institute the same sort of -ent / -ant levelling as the anonymous inventors of Old French spelling did. A little increase in headline ambiguity would be a small price to pay.

Update — Eugene Volokh writes:

This reminds me of the little-known fact that, in Article VII of the Constitution, the date is rendered as “the Seventeenth Day of September in the Year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and Eighty seven and of the Independance of the United States of America.” Many modern printed versions of the Constitution erroneously render this as “Independence,” though I got the National Archives to change their official transcript to properly reflect the original handwritten “Independance.” See "Error in Many Versions of the United States Constitution", 5/14/2010.

Dan Romer said,

November 16, 2019 @ 7:32 am

Two thoughts about your interpretation of the headline. It seems that your reading is more wishful than actual. And BTW:

How does someone actually throw someone "under the bus"? I can see throwing someone out of the bus; but having them land under it while it's moving seems far fetched :)

[(myl) I've always assumed an image of pushing someone off the side of the road in front of an oncoming bus. On that theory, why it's not "push under the bus" rather than "throw under the bus" is unclear. Wikipedia has a "Throw under the bus" article, which gives the history but doesn't seem to clarify the metaphor.]

Philip Taylor said,

November 16, 2019 @ 7:37 am

"A small price to pay" for what gain ? An increase in ambiguity seems to this reader to be a very large price to pay if the sole benefit is to eliminate the need for authors to remember which suffix is required in a particular context.

[(myl) Reading and writing is much more of a roadblock for students in American schools than in places where the language has a more rational orthographic system. Thus according to "Reading Scores on National Exam Decline in Half the States", NYT 10/30/2019:

Only 35 percent of fourth graders were proficient in reading in 2019, down from 37 percent in 2017; 34 percent of eighth graders were proficient in reading, down from 36 percent.

This is partly due to teaching methods and other social factors, but there's good evidence that the transparency (or not) of the orthographic system has a big effect — see e.g. "Ghoti and choughs again", 8/16/2008.

The -ant / -ent mess is a very small part of the problem, but it's part of the problem. ]

Philip Taylor said,

November 16, 2019 @ 9:07 am

I take your point, Mark, but I think that both you and I are of a generation for which expectations were considerably higher. I do not know how the "grade" system maps to age or to type of school, but I remember quite clearly that when I joined Colfe's Grammar School at the age of eleven (in 1958), there were only two boys in the class (class size circa 36) who could not read fluently. The fact that they could not read fluently was sufficiently unusual that I can hear them in my mind's ear even today (over 60 years later), stumbling over what the rest of the class thought were very simple sentences.

I was going to add "and language has not changed significantly over those sixty years, so other factors must be the cause" but then I realised, with some chagrin, that language has changed, and not for the better — even contributors to this intellectually elevated blog have been known to use "gonna", "wanna" and other modern abominations without apparently experiencing any sense of incongruity or inappropriateness. So perhaps the debasement of our language is, at least in part, one of the causes of this decline in literacy.

Copied off-list to my former Classics master to seek his views on the matter.

Chris Button said,

November 16, 2019 @ 9:18 am

But at least in this case the words "confident" and "confidant" are pronounced differently by the majority of speakers. We also have the alternative spelling "confidante" for the latter

Scott P. said,

November 16, 2019 @ 9:24 am

"A small price to pay" for what gain ? An increase in ambiguity seems to this reader to be a very large price to pay if the sole benefit is to eliminate the need for authors to remember which suffix is required in a particular context.

Yes, and this is what many spelling reformers forget: a sentence has one author, but potentially thousands of readers, thus a change that benefits writers to the detriment of readers has a net negative effect.

Jonathan said,

November 16, 2019 @ 9:27 am

The rule of thumb I've used, derived solely from current practice and zero historical knowledge, is that -ent is used for adjectives and -ant for nouns. It's probably good for only about 70% of the time, but it's what I would say to someone trying to learn American English.

It seems to be unrelated to the time-of-borrowing explanation, unless someone wants to argue that at different times English speakers were hungry for different parts of speech. It's hard to imagine a convincing version of this argument, though I'd enjoy seeing one.

Jimmy Hartzell said,

November 16, 2019 @ 9:31 am

Philip Taylor, when you say "using 'gonna' and 'wanna'" do you mean in speech or in writing? In either case, how on earth do you think it has anything to do with other people's poor writing and reading skills? When you say words like "debasement" and imply a vague notion of linguistic hygiene, what's the actual mechanism you're hypothesizing here?

Also, was your school selecting for a certain demographic, and are you comparing that demographic to a broader demographic of today's students?

Philip Taylor said,

November 16, 2019 @ 9:42 am

Jimmy — in writing. I do not believe that it is possible to meaningfully assert that someone said "wanna", since the latter is a spelling, not than a sound.

Mechanism : "dumbing down". When I was at school, "wanna" (etc) did not exist, to the best of my belief (UNIV: British English, 1950's/early 60's). "Ain't", however, did, and had any of my peers used it in writing in any schoolwork, they would have been told, in no uncertain terms, that "ain't" has no place in written English other than in attempting to report the speech (or writing) of others.

Demographics — Colfe's Grammar School, founded by the Rev'd Abraham Colfe, vicar of Lewisham, some 400 years ago, was a traditional British grammar school. Pupils were accepted, regardless of background, if they could pass the 11+ examination and put up a creditable performance at interview.

J.W. Brewer said,

November 16, 2019 @ 9:51 am

I wondered if "confidant" might actually be less common than "confidante", which the google books n-gram viewer says (assuming the data isn't dirty) is not the case although I still think that the OED statement that "confidante" emerged earlier is a signal of something that's relevant here. I have sort of a native-speaker intuition that "confidante" need not be limited to specifically female examples, and that insisting on "confidant" when as here the referent is male is thus sort of fussily overprecise, i.e. exactly the sort of thing you would insist on if you were following the stylebook of a stodgy newspaper like the one at hand. But maybe that's wrong; native-speaker intuitions, including mine, aren't always reliable. In any event, the n-gram viewer does confirm that "confident" is vastly more common than "confidant" and "confidante" put together, and certainly "confidante" is much less likely to be misread as "confident" by a reader who is subconsciously playing the odds that the much more common word of the same approximate spelling is what is intended.

There are some recent book titles that use "confidant" in exactly this circumstance, i.e. when referring to someone male connected to a more prominent male politician, e.g. "Lincoln's Confidant: The Life of Noah Brooks" and "Churchill's Confidant: Jan Smuts, Enemy to Lifelong Friend." But those book titles are not composed in the sort of headlinese that is perhaps unusually prone to garden-path misreadings.

Thomas Hutcheson said,

November 16, 2019 @ 9:56 am

I think a "confidant" (n) is a very useful word which would not be improved by spelling it like "confident" (adj).

jin defang said,

November 16, 2019 @ 10:37 am

I've always seen an "e" on the end of confidant, thereby removing any ambiguity on the part of the orthographically challenged.

Headlines involving politicians with names that aren't just proper names have confused me more than once. Think of Italy's Mario Rumor and Israel's Menachem Begin.

Ralph Hickok said,

November 16, 2019 @ 10:58 am

I've always assumed, on the analogy of blond vs. blonde and "fiancé vs. fiancée. that a confidante was a woman and confidant was a man.

john burke said,

November 16, 2019 @ 11:31 am

Many Northern California lawyers pronounce the third syllable of "defendant" to rhyme with "pant", which I've heard ascribed to long-ago faculty at Boalt Hall, the UC Berkeley law school. It may have become a regionalism, or spread beyond Northern Cal; it may also be used to suggest that the speaker is a Boalt graduate, which is a prestigious identity.

Picky said,

November 16, 2019 @ 12:01 pm

Philip Taylor:

But you went to Colfe’s (as I went to the similar Aske’s nearby — the two schools played each other at rugby) and, as you say, everyone there had passed the 11+, and therefore those who could not read or write confidently were on the whole selected out.

J.W. Brewer said,

November 16, 2019 @ 12:01 pm

Note, by the way that even when the vowel in the final syllable is unreduced a similar problem exists in loanwords from French, e.g. "detente" and "debutante" have the same stressed final vowel at least in AmEng (like confidant/confidante) despite the orthographic distinction.

Coby Lubliner said,

November 16, 2019 @ 12:02 pm

I remember being struck by the defendANT pronunciation used by Christopher Darden in the O.J. Simpson murder trial. Darden went to Hastings, not Boalt, but I suppose that's close enough.

john burke said,

November 16, 2019 @ 12:29 pm

@Coby Lubliner: "They dine with us, or come in the evening, at any rate."

David Marjanović said,

November 16, 2019 @ 3:54 pm

-able vs. -ible is a similar case (-ible if actually borrowed from Latin, -able if composed in English).

These forms have long been much more acceptable in American than in British writing. Consider, too, that a blog comment is not exactly a Queen's Speech.

In speech, they're no less common in Britain than in the US in my limited experience. Of course, I would not be surprised to learn that their distribution in Britain is much more complex than in the linguistically rather uniform US.

Frans said,

November 16, 2019 @ 5:11 pm

@J.W. Brewer

Not to mention in French… :)

Carl said,

November 16, 2019 @ 7:24 pm

I’m really confused by Prof Liberman here. In my American accent, confidant and confident don’t sound anything alike. The stress is totally different. ConfiDANT and confidnt. (How do you type schwa on an iPad?) I get a lot of ant/ent confusions, but not this one.

[(myl) As I wrote,

Of course I know the difference between confident and confidant — and in this case, there are two meanings and two pronunciations as well. But in most cases, the 'e' vs. 'a' choice makes no difference in either meaning or pronunciation, and it's just one more arbitrary thing to learn about English orthography.

]

Andrew Usher said,

November 16, 2019 @ 9:31 pm

Outside of edited writing I'd put no confidence in the gender distinction of confidant(e), and I would't assume the sex from either spelling. Of course the word is really quite rare anyway. I imagine it's somewhat more common in headlines/titles because there's no other one-word description that fits those cases.

I'm puzzled by the reference to 'affairs of love' (now 'affairs') in Johnson's definition; whatever he meant by it, I think of no such connotations today.

Carl: His confusion here was in the _written_ form only; it would not have been ambiguous if spoken, for that very reason. But in writing, that one vowel letter that's normally unstressed and carries no meaning can be misread.

But I can't agree that merging -ant/-ent is a good spelling reform, except for changing the inconsistent (and unetymological) cases like 'dependant' and 'ascendant'. The default form is -ant, yes, but look at pairs like accident/accidental and transcendent/transcendental where the 'e' ends up stressed. I can't think of any such pairs with -ant (they should exist though), but there are ones where -ant/-ance/-ancy goes with -ation. So it's just another part of the morphophonemic structure of English, regular and justifiable.

I can't understand the objection to 'gonna' and 'wanna' either – seems like random peeving for the sake of peeving – unlike "ain't" (which is slowly disappearing anyway), they are assuredly part of standard spoken usage. The distinctive spellings reflect distinctive pronunciations for certain senses, and so, like 'alright', help rather than hinder the reader.

k_over_hbarc at yahoo dot com

Rick Rubenstein said,

November 17, 2019 @ 2:48 am

There's a very simple rule for determining whether it's "ant" or "ent". If it's tiny, eusocial, and haplodiploid, it's "ant". If it's enormous, has a booming voice, and lives in Fangorn Forest, it's "ent".

unekdoud said,

November 17, 2019 @ 4:54 am

Sure, and I suppose people I can't recognize end in "-er", but people that I doubt end in "-or".

Philip Taylor said,

November 17, 2019 @ 5:41 am

Picky (Haberdashers' Askes / Leathersellers' Colfes / selection) — point taken.

Andrew ('random peeving') — Absolutely not. "Gonna" (for "going to") and "wanna" (for "want to") is even more illiterate than "could of" for "could have". I am sure that you would not seek to defend the latter, so why defend the former ? In speech, /ˈkʊd v/ could equally well be "could have" or "could of" but /ˈgɒn ə/ can no more be "going to" than /ˈwɒn ə/ can be "want to".

Rodger C said,

November 17, 2019 @ 12:42 pm

"(-ible if actually borrowed from Latin, -able if composed in English)"

Uh, no. All adjectives composed in English (e.g. "doable") have -able, but not all adjectives in -able are of English origin.

David said,

November 17, 2019 @ 2:59 pm

IIRC, phone company engineers used to say "call-ER" and "call-ED" to name the two ends of a phone conversation, to avoid confusion between the normal pronunciations of "caller" and "called".

Could "defend-ANT" have been used for this purpose?

Andrew Usher said,

November 17, 2019 @ 3:02 pm

Correct, it's a matter of the different Latin declensions, just like -ant/-ent is. The use of -able for new formations is clearly influenced by the word 'able', which is from the same Latin suffix (but belongs in neither class since the root is monosyllabic).

Philip, you are not making sense. Yes, we agree 'could of' is wrong; it is a misspelling of 'could have' or its contraction could've. Your last sentence then implies that spelling the spoken forms at issue as 'going to' and 'want to' is at least as wrong as 'could of', i.e. we _must_ use 'gonna' and 'wanna'! Of course that's absurd, and one doesn't have to use them, but they can no longer be considered wrong given that they are universally understood, accurate, and serve a purpose.

Andrew Usher said,

November 17, 2019 @ 3:20 pm

I missed David's post – no, 'defend-ANT' as he writes it is still stressed on the penult, and I there's no other word it could be confused with in that manner.

Philip Taylor said,

November 17, 2019 @ 5:28 pm

Andrew, that is not what I meant. My point is that unlike "alright" / "all right", "gonna" and "wanna" do not mean anything other than "going to" and "want to", and whilst some may choose to incorporate /ˈgɒn ə/ and /ˈwɒn ə/ into their speech, their spelled-out forms "gonna" and "wanna" have no place in educated writing other than (as with "ain't") in reporting the speech or writing of others.

Andrew Usher said,

November 17, 2019 @ 8:36 pm

Well I take your point, now that you've expressed it sensibly. But I still don't think I completely agree, and surely it doesn't justify the apocalyptic reaction that we inferred of you.

Ellen K. said,

November 18, 2019 @ 11:21 am

In speech, /ˈkʊd v/ could equally well be "could have" or "could of" but /ˈgɒn ə/ can no more be "going to" than /ˈwɒn ə/ can be "want to".

Which, as I see it, is precisely why we need "gonna" and "wanna" in our written language. Because sometimes it's appropriate to write as we speak, or to accurately capture the speech of others.

Now, if someone's writing something like "I'm gonna the store", I'm all for writing "going to" instead. And I would never write "gonna" there. And my mental speech would never have "gonna" there. But replacing "I'm gonna see you tomorrow" with "I'm going to see you tomorrow" seems clunky, and still leaves it in a colloquial register. And "I'm gonna go to the store" being replaced with "I'm going to go to the store" is just bad, in my view. If "gonna" is too informal for what one is writing, then "going to" probably isn't appropriate either.

Rose Eneri said,

November 18, 2019 @ 1:00 pm

From Dr. Liberman's article: "I first interpreted the headline as "Donald Trump is confident that Roger Stone is guilty on all counts, and" (whoops) "he (=Trump) faces up to 50 years in prison"?

But, would not this interpretation have required a comma after Trump?

"Donald Trump, confident Stone guilty on all counts, faces up to 50 years in prison."

Regarding spelling reform, would any confusion arise by eliminating the suffix "ible", and just using "able?" I can never get these right.

BZ said,

November 18, 2019 @ 1:39 pm

@Philip Taylor, but "gonna" and "going to" are not identical. "Gonna" can only be used to denote future tense, not motion, so "I'm gonna work" means "I intend to work", but "I'm going to work" is ambiguous between that meaning and "I am (or will be) on the way to my workplace".

Amy W said,

November 18, 2019 @ 3:20 pm

It seems to me that "gonna" and "wanna" are not really different from "isn't" and "he's." It's just a spelling of a contraction, which varies with appropriateness depending on the formality of writing. I wouldn't normally write out an ordinary contraction like "isn't" to "is not" unless a high level of formality was required. "Gonna" and "wanna" would correspond to a much lower level of formality than "isn't," in my opinion, but not quite as low a level of formality as spelling out other pronunciation differences like "agin" for "again."

Philip Taylor said,

November 18, 2019 @ 3:46 pm

I think I have written more than enough on "wanna" and "gonna", so I will add one footnote and then stand back. I am reasonably confident that there must be a marked difference between the acceptability of these two ?words? in British English and American English. I do not believe for one second that a British school teacher would allow either in a written essay (other than as a part of direct speech) without comment; I would be interested to know whether the same would be true for American school teachers.

Andreas Johansson said,

November 19, 2019 @ 7:51 am

Regarding "confidante" and affairs of love, when I first encountered the word it was in a context (a man doing favours for a woman) that made me assume it meant, or was an euphemism for, "mistress".

Andrew Usher said,

November 19, 2019 @ 6:19 pm

I can't say that it never was used to mean 'mistress', but probably it wasn't.

That brings to mind that I first saw the word 'amanuensis' in a similar context, and assumed the same thing – especially seeing Latin 'ama-' (love) in it, which is actually not there.

Amy W said,

November 19, 2019 @ 9:14 pm

Philip Taylor,

I am an American who teaches composition at an American community college. What I'd allow to pass "without comment" depends a lot on the goals of the assignment and what else is going on in the paper–I target my feedback to what I consider the most important issues rather than feeling I have a duty to mark every error.

That said, I would agree with your general sentiment that "gonna" and "wanna" are inappropriate in most academic essays, except in cases of quoted speech or perhaps some kind of purposeful code meshing. I don't extend this to all contractions–I find "it's" and "can't" to be perfectly fine in all but the most formal writing.

Ellen K. said,

November 19, 2019 @ 9:23 pm

But aren't "going to" and "want to" also inappropriate in most academic essays? It's a rather moot point whether or not the contraction is acceptable if the long form is also not appropriate. Seems to me in an academic essay "will" and "would like to" would be preferable, usually.

Amy W said,

November 19, 2019 @ 11:03 pm

Ellen K., well, my standards for formality aren't that high for many of the freshman comp assignments. For example, a freshman comp paper might ask a student to reflect on the value of their course of study. In such a paper, a sentence like "Our society is going to need more nurses" or "Many students want to earn more money" seems perfectly fine to me. But "gonna" or "wanna" would be far too casual unless there was some kind of relevant purpose to the language choice.

I'd be pretty surprised if "going to" (in the sense of "gonna") and "want to" are completely absent in academic journal articles, even outside quotations, although other formulations might be more common.