R.I.P. Knud Lambrecht

« previous post | next post »

I learned yesterday that Knud Lambrecht died on Friday 9/6. As you can see from his Google Scholar page, his scientific work centered on an important area that deserves more than the (already considerable) attention that it gets from linguists — the relations between "information structure" and the form of sentences.

What that means is explained in the preface of his 1994 book Information Structure and Sentence Form: Topic, Focus, and the Mental Representations of Discourse Referents:

This book proposes a theory of the relationship between the structure of sentences and the linguistic and extra-linguistic contexts in which sentences are used as units of propositional information. It is concerned with the system of options which grammars offer speakers for expressing given propositional contents in different grammatical forms under varying discourse circumstances. The research presented here is based on the observation that the structure of a sentence reflects in systematic and theoretically interesting ways a speaker's assumptions about the hearer's state of knowledge and consciousness at the time of an utterance. This relationship between speaker assumptions and the formal structure of the sentence is taken to be governed by rules and conventions of sentence grammar, in a grammatical component which I call INFORMATION STRUCTURE, using a term introduced by Halliday (1967). In the information-structure component of language, propositions as conceptual representations of states of affairs undergo pragmatic structuring according to the utterance contexts in which these states of affairs are to be communicated. Such PRAGMATICALLY STRUCTURED PROPOSITIONS are then expressed as formal objects with morphosyntactic and prosodic structure.

My account of the information-structure component involves an analysis of four independent but interrelated sets of categories. The first is that of PROPOSITIONAL INFORMATION with its two components PRAGMATIC PRESUPPOSITION and PRAGMATIC ASSERTION. These have to do with the speaker's assumptions about the hearer's state of knowledge and awareness at the time of an utterance. The second set of categories is that of IDENTIFIABILITY and ACTIVATION, which have to do with the speaker's assumptions about the nature of the representations of the referents of linguistic expressions in the hearer's mind at the time of an utterance and with the constant changes which these representations undergo in the course of a conversation. The third category is that of TOPIC, which has to do with the pragmatic relation of aboutness between discourse referents and propositions in given discourse contexts. The fourth category is that of FOCUS, which is that element in a pragmatically structured proposition whereby the assertion differs from the presupposition and which makes the utterance of a sentence informative. Each of these categories or sets of categories is shown to correlate directly with structural properties of the sentence.

If this seems a little overwhelming, consider the abstract of William Frawley's 1997 review in the journal Studies in Second Language Acquisition:

When I saw that this book was a comprehensive study of the relationships across discourse, grammar, and prosody, my spirits sagged. “Oh, no,” I thought. “Not this story again.” But 20 pages into the book I realized that Lambrecht had taken a new and sobering approach to the subject, tackling a very hard subject and giving convincing answers with clear data.

Or better, read Lambrecht's chapter "Constraints on subject-focus mapping in French and English: A contrastive analysis", from the 2010 volume Comparative and contrastive studies of information structure, which explains the issues clearly, with simple examples that will be helpful for second-language learners transitioning into or out of English. The abstract:

Grammars reflect universal constraints on the mappings between the information structure of propositions and the formal structure of sentences. These constraints restrict the possible linkings between pragmatic relations (topic vs. focus), pragmatic properties (given vs. new), semantic roles (agent vs. patient), grammatical relations (subject vs. object), and syntactic positions (preverbal vs. postverbal, etc). While these mapping constraints are universal, their grammatical manifestation is subject to typological variation. For example, although spoken English has been shown to strongly prefer pronominal over lexical subjects, hence to avoid focal subjects, it nevertheless freely permits subject-focus mapping in certain sentence-focus and argument-focus constructions. In spoken French, in contrast, subject-focus mapping is unacceptable if not ungrammatical in most environments. Spoken French shows a near one-to-one mapping between focus structure and phrase structure: Topic expressions occur overwhelmingly in preverbal position and in pronominal form, while focus expressions occur postverbally. To avoid violating this near one-to-one mapping constraint, spoken French makes abundant use of grammatical realignment constructions, especially clefts. Some of these constructions do not exist in English, or have a much more restricted distribution in that language.

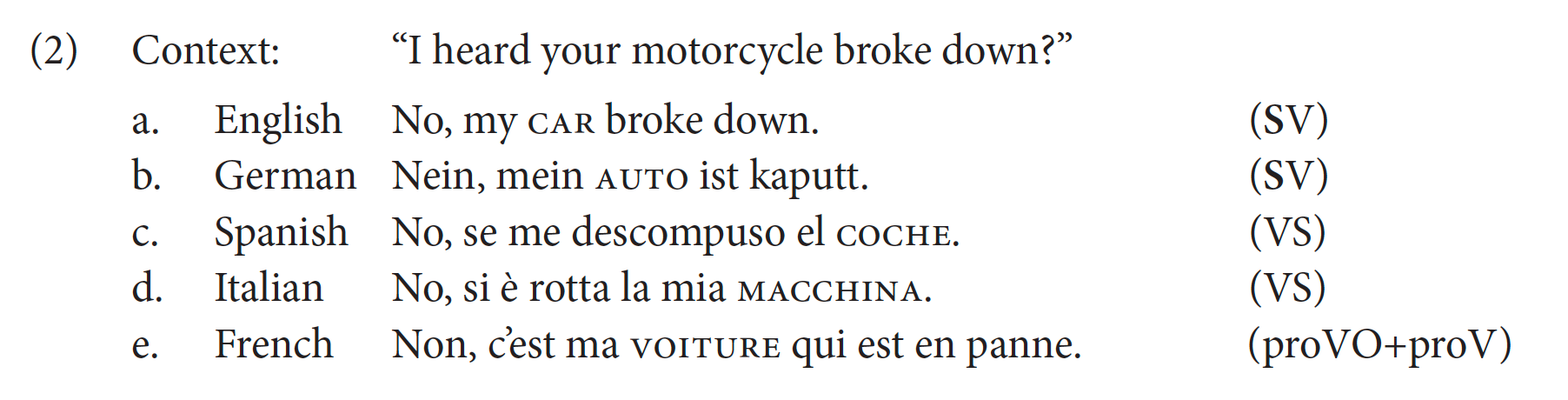

One of that article's many enlightening examples:

Update — An obituary written by Anna Piller can be found here.

Marc Hamann said,

September 9, 2019 @ 6:37 am

Contra: No, it's my car that broke down.

[(myl) Exactly. As Lambrecht wrote, "[A]lthough spoken English has been shown to strongly prefer pronominal over lexical subjects, hence to avoid focal subjects, it nevertheless freely permits subject-focus mapping in certain … constructions." ]

Rodger C said,

September 9, 2019 @ 6:40 am

@Marc Hamann: To me that sounds literary and, in fact, calqued on French.

mollymooly said,

September 9, 2019 @ 7:10 am

Clefting is widespread in Irish and hence common in Hiberno-English. The Simpsons' Irish episode had a sequence of clefts ending with "So! 'tis our syntax you're deprecatin'!"

Rod Johnson said,

September 9, 2019 @ 8:58 am

Lambrecht's work was fascinating. When I was working on Burmese, which has lots of "zero" subjects and objects, I always wanted to, apply his ideas to try to understand where verb arguments appeared and where they didn't, but never quite got around to it. RIP.

Ben Zimmer said,

September 9, 2019 @ 7:11 pm

@mollymooly: I had to look up that exchange from The Simpsons…

Irish Policeman #1: So, it's a smoke-easy you're running then?

Homer: Uh-oh! (tries to flee with Grampa)

Irish Policeman #2: Toots! It's escaping you're thinking of then?

Homer: I can't tell if those are questions or statements!

Irish Policeman #1: So, it's our syntax you're criticizin' then?

("In the Name of the Grandfather," S20E14, Mar. 22, 2009)

Chris Button said,

September 9, 2019 @ 8:18 pm

What a shame I'm only hearing about his work now. Out of curiosity, did he look into the use of intonation and the influence that had on what would be considered a "common" versus "restricted" distribution in different spoken languages?

Martin said,

September 10, 2019 @ 1:57 am

@RodgerC: 'No, it was my *car* that broke down' (note 'was') seems idiomatic enough to me.

Rodger C said,

September 10, 2019 @ 7:01 am

Oddly, with "was" it works fine with me. I'd even say "It was my car broke down."

Andrew in the UK said,

September 10, 2019 @ 11:28 am

> died on Friday 9/6.

I read that at first as 9 June, and wondered why it had taken so long for the news to travel. Please use unambiguous date formats.

JPL said,

September 10, 2019 @ 7:47 pm

Knud Lambrecht. Wow! An absolutely interesting line of inquiry. Who's going to take it up, or who else has been taking this line?

"It is concerned with the system of options which grammars offer speakers for expressing given propositional contents in different grammatical forms under varying discourse circumstances. [….] In the information structure component of language, propositions as conceptual representations of states of affairs undergo pragmatic structuring according to the utterance contexts in which these states of affairs are to be communicated. Such PRAGMATICALLY STRUCTURED PROPOSITIONS are the expressed as formal objects with morphosyntactic and prosodic structure."

"Grammars reflect universal constraints on the mappings between the information structure of propositions and the formal structure of sentences."

If I understand him accurately, this means that, given a particular linguistic expression, say a sentence, the grammar offers "a system of options" for differences in the propositional content expressed such that there is a class of individual propositions that are equivalent in, say, core propositional content, but differ in terms of various pragmatic considerations. These differences are then indicated by the morphosyntactic resources of the language being used. This means that the term 'proposition' should refer to a logical individual and should be distinguished from the class of propositions equivalent in terms of, say, core propositional content. (I guess this would include the active- passive cases that Frege noticed, but I'm not sure he kept the differences as well as the equivalences.) But there is a clear distinction here between 'proposition' and 'sentence'. Describing the significance of the particular mappings a language makes possible has got to be a difficult task. Formal language mode seems to involve similar considerations: Why, e.g., do we need to say that "if a = b, then b = a"? Maybe I'm off the mark here, or maybe this is well known, but I think I have to read some of Lambrecht's work. Thanks Mark!