Dysfluency considered harmful

« previous post | next post »

… as a technical term, that is. Disfluency is no better, although the prefix is less judgmental. There are two problems:

- These terms pathologize normal behavior, creating confusion between pathological symptoms and common phenomena in normal speech, which may be different not only in their causes and their frequency but also in behavioral detail;

- Applied to normal speech, these terms often treat intrinsic aspects of the content and performance of spoken messages as if they were disruptions or failures.

My suggestion: we should use the term interpolation for silent pauses, filled pauses, filler words or phrases, repetitions and corrections, etc. This leaves open the question of whether such interpolations are normal or pathological, and whether or not they're an intrinsic part of the content and performance of the message.

Merriam-Webster's definition of dysfluency/disfluency is

an involuntary disruption in the flow of speech that may occur during normal childhood development of spoken language or during normal adult speech but is most often symptomatic of a speech impairment

especially : a disorder of vocal communication that is marked by frequent involuntary disruption or blocking of speech (as by repetition of all or part of a word or by prolonging vocal sounds) and typically has an onset during childhood

Wikipedia focuses on the phenomena that are common in everyone's everyday speech, leaving out the use of the same terms for behaviors viewed as disorders or symptoms of pathology:

A speech disfluency, also spelled speech dysfluency, is any of various breaks, irregularities, or non-lexical vocables that occurs within the flow of otherwise fluent speech. These include false starts, i.e. words and sentences that are cut off mid-utterance; phrases that are restarted or repeated and repeated syllables; fillers, i.e. grunts or non-lexical utterances such as "huh", "uh", "erm", "um", "well", "so", "like", and "hmm"; and repaired utterances, i.e. instances of speakers correcting their own slips of the tongue or mispronunciations.

Amazingly enough, the OED apparently has no entry for dysfluency/disfluency (perhaps because it's a relatively recent word?).

Nine of the first ten hits on Google Scholar for dysfluency, and three of the first ten hits for disfluency, deal with symptoms of disorders (Parkinsonism, Down's syndrome, stuttering, etc.).

I'll leave aside for now the general question of whether the medicalized "dysfluencies" are the same as the everyday "dysfluencies" and just assert that it's a mistake to use terminology that presupposes an answer to that question.

But let's note in passing that the speech pathology referred to as stuttering or stammering is generally very different from the rapid repetitions common in everyday speech. As an example, listen to this short passage from Terry Gross interviewing Illeana Douglas on Fresh Air in 2015. Do you hear any stuttering?

Here's the show's transcript of that segment:

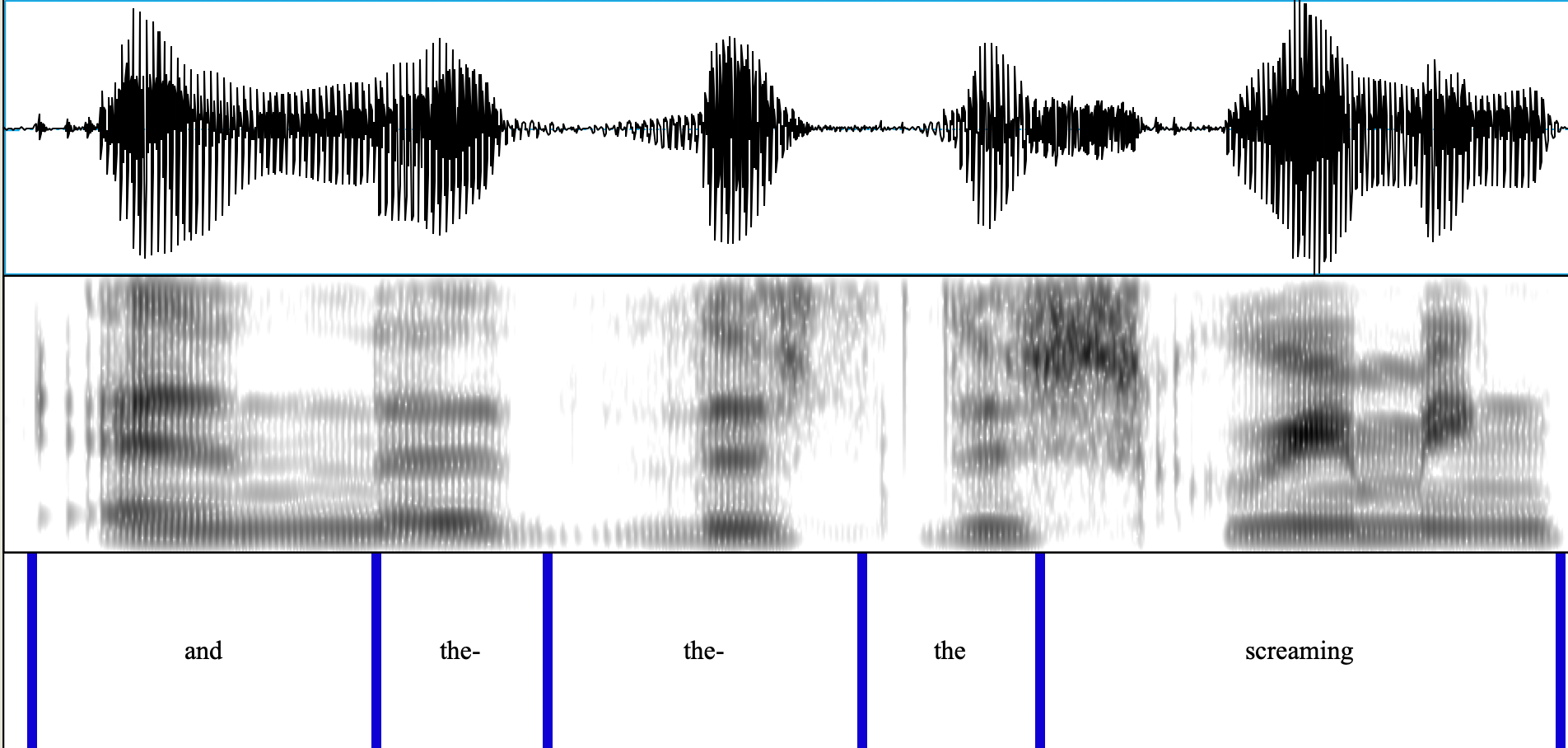

But here's Terry Gross's last sentence, where careful listening will reveal that she repeats the word the three times within half a second:

And the- the- the screaming tape loop in the background is you, right?

Zeroing in still further:

As you may well not have noticed, Terry Gross also repeats several words earlier in that segment. Transcriptionists generally leave out such things, which with tongue in cheek I used to call "fluent dysfluencies". A better term would be "rapid repetitions" — and they're very common. Terry Gross is a skilled professional speaker and one of the world's great interviewers, but in a selection of her interviews where I've "dis-edited" the transcripts to restore various sorts of interpolations, she has 579 rapid repetitions in 23,427 words, for a rate of 2.5%. This is not evidence that Terry Gross suffers from stuttering — though in comparison, the word the has a frequency of 3.2% in the same collection.

And if we add in the ums and uhs and likes and you knows and I means, her overall interpolation rate rises to 4.6%. This is well within the normal range — but it would also be an enormous mistake to see this as representing her rate of "involuntary disruptions in the flow of speech" (Merriam-Webster) or "breaks, irregularities, or non-lexical vocables" (Wikipedia). A significant fraction of these interpolations are clearly planned aspects of her performance, contributing to its communicative effect.

This is especially clear in the case of silent pauses. A pause may reflect a disruption or delay in speech planning, but often it's a sign of the syntactic, semantic and rhetorical structure of the message. And sometimes it's both at once.

Silent pauses can have a clear communicative function even when they occur in places where they don't belong from a purely structural point of view, for example between a determiner and the following noun phrase. Here's an example from another Fresh Air interview:

This is Fresh Air, and if you're just joining us, my guest is Jill Soloway, she's the

creator and show-runner of the Amazon TV series

Transparent

The 218-msec silence between "us" and "my" marks a phrase break — but the 310-msec silence between "the" and "creator" — like the 473-msec silence between "series" and "Transparent" — is there to add emphasis to what follows, not to give Terry Gross time to remember where to look in her notes.

Many researchers have suggested that "filled pauses" — um and uh in American English — often function communicatively, sometimes just as delay signals but also often as markers of discourse structure (see e.g. here).

It's easy to find suggestive examples of this kind in Terry Gross's interview techniques, such as the common structure

<FRAMING INFORMATION> um <QUESTION>

Here's an example from her 2015 interview with Shonda Rhimes:

so your first big show, of course, was "Grey's Anatomy." Why was your first show a medical show?

I mean, there had been very successful shows before that.

um why did you want to do a medical show yourself,

and what did you think would be different

about your show?

Another example, from an interview with Willie Nelson:

now

the last couple of summers you've been touring minor league

baseball parks with- with Bob Dylan

um what do you feel you

and Bob Dylan have most in common as friends or as

songwriters or lovers of music?

In an interview with Carrie Brownstein:

You didn't know it at the time, but your father was gay. He didn't come out until he was 55, and you were probably in your 20s by then.

um Do you think he knew at the time, when you were in your teens and living at home with your parents?

Do you think he knew he was gay?

um so- so when- when you look at your writing now – and again like we- we mentioned, you turned 70 this year

have you ever cared much about like, legacy, like, how your books are regarded

in- in- in- the future and are- will they be read in the future and how will you be interpreted and

how much do you need to write?

um and I'm wondering what you thought about that as a young man compared to how you feel about that now?

OK — enough, or too much.

But I hope I've persuaded you that it's at best tendentious to describe as "dysfluencies" a collection of ordinary-language behaviors whose only real common characteristic is that they're usually omitted from written transcripts. Each instance may reflect a failure at some level of planning or performance, or alternatively a communicatively relevant part of the plan or the performance — or both at once.

And it's often wrong to see these interpolations as interrupting "the flow of otherwise fluent speech", since in many cases the resulting speech stream flows more smoothly than regions without such "dysfluencies". A young person of my acquaintance, criticized by a teacher for over-using the discourse marker like, responded that "for me, like is the engine of speech".

Philip Taylor said,

May 19, 2019 @ 10:50 am

Leaving aside the {dys|dis}fluency aspects just for the moment, I am intrigued by the use of the following "considered harmful". The first usage of "X considered harmful" of which I am aware is Edsger W. Dijkstra's EWD 215, originally entitled "A Case against the GO TO Statement" which was published as "Go To Statement Considered Harmful" in Communications of the ACM 11 3 (March 1968), 147–148. But was it therefore a Comms ACM sub-editor who actually coined this most useful phrase, and is this therefore truly the first such usage thereof ? I would dearly love to know.

[(myl) The two-word sequence "considered harmful" seems to have been used fairly often over the centuries. Some examples from Google Books search:

1920: Home-talent plays were considered harmful to a community by 3 ministers, while 22 saw no harm in them.

1913: The Orthoptera (crickets and cockroaches) are considered harmful, the Hymenoptera (chiefly ants) neutral or harmful, …

1905: From the standpoint of pharmacology and care of health of the public, the application of borax preparations as preservatives must be considered harmful and deleterious to health.

1904: The whole activity of the Republican party is considered harmful by the Radical party, and vice versa, the whole activity of the Radical party, if the power is in its hands, is considered harmful by the Republican party and by others.

1901: Such salts as sodium chloride, or common table salt; magnesium chloride; and magnesium sulfate, or epsom salts, are considered harmful.

1899: This was clearly both an adulteration and a fraud, and as such was recognized as reprehensible, not because the alum was considered harmful, but because it made possible the sale of inferior flour as a superior article.

1894: Lemonade, for general use, is considered harmful. Still, it may be drunk when a refreshing drink is thought absolutely necessary.

1889: It gives a brief review of changes made by legislative enactments of the past year, followed by short statements of the open seasons for taking furs, provisions relating to propagation of fur animals, and bounties offered for the destruction of predatory species, or those considered harmful.

But it was Dijkstra's title that turned it into an idiom, as far as I know.]

Philip Taylor said,

May 19, 2019 @ 12:25 pm

Yes, "X {is|are} considered harmful" is in widespread use and completely unremarkable as far as I can see — it was the usage "X considered harmful" with no explicit {is|are} verb that particularly interested me.

Noel Hunt said,

May 19, 2019 @ 5:16 pm

I believe I've seen these 'interpolations' or 'dysfluencies' called 'hesitation phenomena' or the like, because 'fillers' at least serve that purpose.

[(myl) Sometimes. Sometimes they seem to express emphasis, or topic shift, or something else.]

Julian said,

May 20, 2019 @ 1:14 am

To disedit fluent 'disfluent' speech (like the 'the the the' example) accurately is surprisingly hard. We're so used to screening certain things out that it's hard to hear them even when you're listening out for them.

rosie said,

May 20, 2019 @ 1:48 am

Seeing as they denote the unintentional results of the speaker's less than perfect action, what is wrong with the existing terms? To say that those terms pathologize is to use that word too loosely, I think — there is no suggestion that medical treatment is needed.

To prescribe the term "interpolations" for them fails to distinguish them from what really are interpolations, such as your last example, "like".

Bob Ladd said,

May 20, 2019 @ 5:19 am

Until reading Philip Taylor's comment and Mark's reply, I was entirely unaware of "considered harmful" as an idiom. Is this a computer science thing, or is it more general and I've simply missed it?

[(myl) It's more or less a CS thing — page through Google Scholar's 40,000 hits> and see.]

Andrew M said,

May 20, 2019 @ 9:02 am

I'm puzzled by this: isn't 'X considered harmful' just the natural way to express 'X is considered harmful' in a headline? (In the same way 'President shot' would be a legitimate headline, though we wouldn't put it that way in ordinary speech.)

ktschwarz said,

May 20, 2019 @ 9:42 am

unintentional results of the speaker's less than perfect action: Mark Liberman is arguing that Terry Gross's pauses and fillers are NOT unintentional and NOT less than perfect; they "function communicatively," and she wouldn't change them even if she could. Even replacing um, uh, and the-the-the with silence would change the tone of the interview, making it sound less spontaneous, like giving a speech instead of inviting the interviewee into a give-and-take.

Tim Morris said,

May 20, 2019 @ 9:49 am

ktschwartz, exactly. The "NPR stammer" has been observed, and is presumably very deliberate. I suspect it both makes the performance sound more spontaneous, and makes the speaker seem more personable, less of a highbrow know-it-all. See this blog post: https://rebeccakuder.com/2010/09/24/stammering-on-npr/

J.W. Brewer said,

May 20, 2019 @ 10:49 am

To Andrew M.'s point, conventions for article titles in scholarly journals are often different (because of less pressure to minimize total character count) than conventions for headlines in newspapers. I assume the Dijkstra title (even if someone at the journal rather than Dijkstra himself came up with it) became an idiom/snowclone/cliche because something about it made it much more striking-sounding than the average CS technical article of its time, although whatever made it sound so striking may not have been the copula deletion.

RfP said,

May 20, 2019 @ 4:53 pm

Although I've been a technical writer for quite a while now, I was a software engineer for many years, starting in the early '80s, when structured programming was a really big deal. The Wikipedia Considered harmful article notes that the published title of Dijkstra's letter "Go To Statement Considered Harmful" was thought up by Communications of the ACM editor Niklaus Wirth, and its pungency is a big reason for why this phrase is so widely known in software engineering. But I don't think it would have had anywhere near the impact in that respect if it weren't for the importance of the article itself as a battlecry for the creation and institutionalization of structured programming itself.

For both reasons, a few other seminal papers borrowed this phrasing for their own titles, including "Global Variables Considered Harmful" and, to the best of my recollection, another paper advocating functional programming over procedural programming.

As for its prevalence in "computer science," I vividly remember taking a Java course in 1999 with a well-known advocate of object-oriented programming who was proud to differentiate himself as a software engineer from those lowly mortals who were mere "computer scientists." Although I don't share his opinion on this, the distinction does seem useful in understanding the scope of this trope, as it were. If it were confined to computer science departments—that is, if it hadn't escaped from academia—it wouldn't be anywhere near as well-known as it has become "out in the wild," among people who are part of the broader high tech culture.

RfP said,

May 20, 2019 @ 4:54 pm

And no, I wasn't necessarily trying to allege "Wikipedia Considered harmful"!

I tried providing a link, which got swallowed…

RfP said,

May 20, 2019 @ 5:32 pm

As for the NPR stammer, I was kind of shocked a few months ago when the computer directing me through my call to the bank used it! I don’t remember exactly what it said, but it was something along the lines of, “Okay, umm, (slight pause) please enter your account number.”

As if it needed to think carefully about how to tell me exactly what I needed to do.

Richard said,

May 20, 2019 @ 6:12 pm

I teach English pronunciation to professionals, and a lot of time they say, "I don't want to ever use fillers or gaps because that's sloppy communication," and I have to explain that native speakers use these to communicate more clearly. They're necessary to signal register, certainty, stance, and a variety of other pragmatic concerns. Talking like an academic paper being read aloud is not appropriate communication for most settings. De-pathologizing those with the word "interpolation" is a good move.

Andrew Usher said,

May 20, 2019 @ 9:27 pm

First I'd never seen the spelling with 'dys' before, and would have considered it an error. Certainly 'dis-' is to be preferred, both by etymology and meaning.

It's a useful catch-all term for the sounds found in speech that aren't fluent speech; 'interpolation' is not broad enough, and to me is misleading given the usual meaning of that word. A disfluency is something that, generally, the author of which would admit was a flaw, or at least would not want transcribed in writing. What you call 'fluent disfluencies' are normally unnoticed by both speaker and hearer, and not intentional even subconsciously.

I know I never produce an intentional disfluency, yet my speech contains them. (I don't consider silence to be one, following the same reasoning). Contrary to the above, I imagine that if some one spoke entirely without disfluencies (but otherwise unchanged) you probably wouldn't even notice, unless you were looking for it – for example with recorded voices; no one remarks on their absence, but on their presence, as above. It's really not different with real voices; while you won't catch all the disfluencies the speaker does make, you won't catch any that he doesn't!

There've been posts here showing that President Trump makes a considerably lower rate of disfluencies than most people in similar circumstance; yet no one could say that he sounds robotic or whatever. That idea, seemingly implied by Richard's above comment as well as the tenor of the whole discourse, is absurd.

That some people do use (or train themselves to use) disfluencies on purpose as a part of style is no ground for such generalisation.

k_over_hbarc at yahoo.com

Jerry Packard said,

May 21, 2019 @ 11:34 am

I've always understood the 'dys-' prefix to be in contrast to an 'a-' prefix, where 'dys-' means something like 'born without' and 'a-' means 'loss of.' My favorite example of the contrast is 'dyslexia' vs. 'alexia', with the first meaning inherent problems with reading and the second meaning loss of the ability to read. Same with 'dysphasia'/'aphasia' and 'acalculia'/'dyscalculia.'

yoandri dominguez said,

May 21, 2019 @ 10:38 pm

Performative triplication