Crowdsourcing the lexicon

« previous post | next post »

A recent piece by Eric Mack on CNET News begs everyone — and in particular the dictionary publishers at Collins — to "stop crowdsourcing the English language." What he's grousing about is that Collins has now included entries for a few (by no means all) of the 5,000 newly current words that readers have pointed out to them.

What do people like Eric Mack think is the source of the information in dictionaries if it does not in effect come from crowdsourcing?

Words have the meanings they do because people use them with those meanings. It's not as if there was some independent source we could turn to for better accuracy if we thought perhaps everyone was wrong about what serendipity or aggregation means. The reason you can't use serendipity and aggregation to mean "knife and fork" is that we who know them use them otherwise (and for this purpose, the people who don't know them simply don't matter; they can ask us). It is non-negotiable: We, the crowd, the native speakers of English whose words these are, have spoken.

If you don't want to know what is currently meant by people who use the words amazeballs, blootered, denialist, fanboy, fandabidozi, frenemy, K-pop, oojamaflip, squadoosh, vom, or zhoosh, then don't look them up; it will do you no harm that they are there in the dictionary and you could have looked them up.

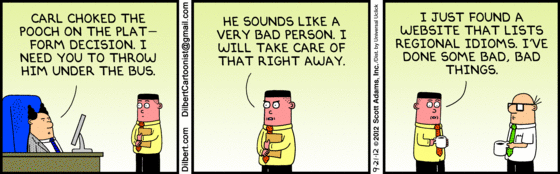

But if you do need to know their meanings for any reason, what exactly is supposed to be the argument that Collins should deliberately keep that information from you? Surely not that these words fall into the ill-defined class of expressions we call slang. First, Collins agrees that they're slang and marks them as such; and second, you sometimes need to know what slang means as well. Look at what happened to Asok when he didn't have the right lexicographical information:

[Thanks to Daniel Hieber for the tip-off.]